Cross

Bones' last phase of use as an active graveyard began just as the resurrection men's era was drawing to a close. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, St Saviour's churchwardens would battle fiercely against health experts and poverty campaigners to keep the site open, despite clear evidence that it was spreading fatal disease through the nearby slums.

Cross

Bones' last phase of use as an active graveyard began just as the resurrection men's era was drawing to a close. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s, St Saviour's churchwardens would battle fiercely against health experts and poverty campaigners to keep the site open, despite clear evidence that it was spreading fatal disease through the nearby slums.

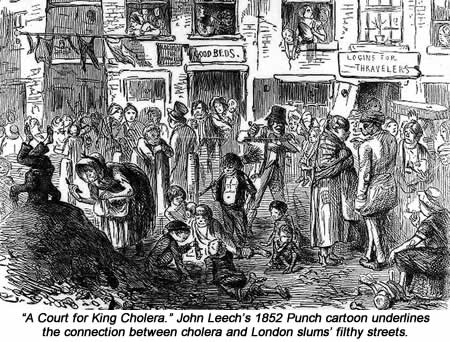

Realising in 1831 that the cholera epidemic already raging through Germany, Hungary and Russia was sure to reach London soon, the national government issued St Saviour's authorities with a list of urgent measures required to clean up their notoriously filthy parish. At the top of this list was a demand to sort out the disgusting state of their pauper burial ground at Redcross Way. "They didn't have germ theory really at that point, but they did know that dead bodies were not healthy and that it's not particularly great to have charity schools right in back of this heaving, enormous graveyard," the Souhwark historian Patricia Dark told me. In his report for the BBC's Crossbones Girl programme, David Green adds: "The dominant theory of the spread of disease was that it spread by 'miasmas' arising from putrefying bodies and rotting organic matter. The cholera outbreak heightened those fears."

Cross Bones was one big miasma by this point, so St Saviour's created a committee to report on just how bad the over-crowding there really was and suggest what practical measures could be taken to alleviate it. The committee, set up in November 1831, convened again to draft its response on March 17 the following year and it's instructive to compare their hard-hitting draft from that meeting with the final report published. Here's a key extract from the draft, followed immediately by the same paragraph as it appeared in the final report:

Draft: "The Committee are of the opinion it would be desirable to clear a small portion of the burial ground and make a depth of 12 feet at the least and place the old coffins therein and by that means provide more burial ground and that in future graves of not less than 12 feet at the least under the direction of a committee."

Final report: "The Committee are of the opinion it would be desirable to provide/make graves of not less than 12 feet deep under the direction of a committee."

As the MoL points out, this final report seems to have been arrived at by the simple expedient of crossing out anything that looked too inconvenient or demanding in the draft. Quite what political in-fighting went on in determining these deletions, I don't know, but the end result was to eliminate any recommendation to clear the existing congestion at Cross Bones. Instead, it simply suggested that new graves there should be dug a lot deeper in future. It was St Saviour's churchwardens who ran the parish burial grounds and we must assume they were responsible for eviscerating the report in this way - because it's pretty clear the committee itself was not impressed.

In April 1832, with cholera now in London, the committee wrote to St Saviour's vestry expressing its concern. "Having viewed with much attention the Cross Bones Burial Ground, we find it so very full of coffins that it is necessary to bury within two feet of the surface, which we consider, especially under the alarming disease now raging, very improper," their letter says. "We also find that, on a partial opening of the ground, the effluviem is so very offensive that we fear the consequences may be very injurious to the surrounding neighbourhood. We are therefore of the opinion under such circumstances and the expectation of close, warm weather that the Ground ought to be immediately closed." (157)

That seemed to hit home with the churchwardens, who decided at their next vestry meeting to empower the committee to close Cross Bones down, raise the level of earth there by bringing in additional top soil and re-open the site only when it was restored to a fit state. It was only a few days, however, before the committee realised that it didn't have anything like enough money at its disposal to complete the necessary work, so it simply chained up the gates at Cross Bones instead. That lasted about a year, at which point the growing pressure from so many cholera and typhus deaths convinced the vestry to put Cross Bones back into use. By the end of 1833, it was once again as busy as ever. (158)

Although London's total cholera deaths retreated somewhat between the epidemic spikes of 1832, 1841, 1854 and 1866, both it and typhus remained a constant presence in the city's poorest boroughs. In 1837, the London Fever Hospital named St Saviour's as one of London's "constant seats of fever from which this disease [typhus] is never absent". In the following year, we have figures showing the parish's population as 31,711, of whom 1,856 (or nearly 6 per cent) were registered paupers. Two hundred and ninety-four of those paupers (16 per cent) are reported as contracting either cholera or typhus in 1838 alone, of whom nearly one in four died.

Both cholera and typhus are commonly contracted from drinking dirty water, so these statistics should not surprise us. Seven years on from the Government's order that St Saviour's must introduce some rudimentary hygiene to its slum neighbourhoods, the parish still had open sewers in every street and as many as 150 people sharing a single Mint Street lodging house. "In much of the low-standard housing of this period, disposal of waste from privies was a major health hazard," the MoL says. "The inhabitants of the area were unwilling or unable to pay for the proper disposal of sewage. This led to waste being either directly dumped into the Thames, or in a cesspool beneath the floor of the house. Records show that solid excrement was often heaped-up to be sold." (159)

As if all that weren't bad enough in a time of cholera and typhus, diseased corpses in St Saviour's would often remain above-ground for well over a week. Many of the poorest families in Southwark were Irish and wanted to observe that country's custom of holding open-casket wakes and having the family watch over a dead body for several days before burial. There was nowhere to lay out a dead relative except in the family's own very cramped living quarters, so that's the space they used. Lacking the money to provide anything but the most basic funeral in the parish's foulest burial ground, what other way did they have to honour their dead?

Speaking at about this time, the undertaker John Wyld said he had known poor families to keep a corpse laid out at home for weeks. "In cases of rapid decomposition of persons dying in full habit, there is much liquid and the coffin is tapped to let it out," he told Sir Edwin Chadwick's enquiry into urban burial grounds. "I have known them to keep the corpse after the coffin had been tapped twice, which has of course produced a disagreeable effluvium." (160)

At the pauper graveyards in any major British city, Wyld added, there would be many funerals scheduled for every hour of the day. "During last Sunday, for example, there were 15 funerals all fixed during one hour at one church," he told the enquiry. "I have seen funerals kept waiting in the churchyard from 20 minutes to three-quarters of an hour." In cases like these, he said, the presiding minister would make everyone wait until the hour's full contingent of funerals had arrived, say a hurried service over the whole bunch of them in one go, then watch them buried in a single trench. Some pauper grounds managed this process better than others, I'm sure, but if Wyld's testimony represents the average state of affairs, it's probably safe to assume that Cross Bones was even worse.

Accounts differ on exactly what happened to the site between its 1833 re-opening and the vestry meeting of 1839 which I'm about to describe. Some say the whole ground was closed again around 1837, some that it was only the most crowded area of all - known as the "Irish corner" - where new burials were banned. What we do know is that a two-year break in new burials in the Irish Corner allowed that area's remains to be cleared away around the end of 1838, making room for about a thousand new corpses to be buried there in the future.

The sheer pressure of bodies requiring burial somewhere in St Saviour's remained as heavy as ever so, in February 1839, the parish churchwardens met to discuss getting Cross Banes back into full use. One of those attending this meeting was a surgeon called George Walker, who later described its proceedings in his book Gatherings From Graveyards. "One gentleman argued that if the graves had been made deeper, hundreds more corpses might have been buried there," Walker writes. "Another admitted that it really was too bad to bury within 18 inches of the surface in such a crowded neighbourhood; and it was even hinted that 'the clearing', viz. the digging up of the decayed fragments of flesh and bones, with the pieces of coffin etc, would be the best course, were it not for the additional expense. The fund of the vestry and the health of the living were here placed in opposite scales: the former had its preponderance." (161, 162)

The vestry ended this meeting with a decision to pass formal responsibility for re-opening Cross Bones to the site committee it had created eight years earlier, but left the committee in no doubt what decision it was expected to make. Clearing Cross Bones completely was far too expensive to consider, but it was imperative to get the site back to full operation immediately. The committee had no choice but to agree.

As a medical man, Walker was outraged to see St Saviour's parish finances put before its inhabitants' lives like this. He was equally disgusted by the state of non-conformist burial grounds in St Saviour's, including both the Quakers' graveyard in Ewer Street and the Congregationalists' ground (a former plague pit) in Deadman's Place. Both sites, he said, were "literally surcharged with dead" and "present a repulsive aspect". Walker also reports a conversation with one Southwark gravedigger - he doesn't say from which particular ground - who admitted that new corpses could be buried in his graveyard only through "management" of those already interred. When asked what this management consisted of, the man became evasive. "He replied he would be a fool to tell anyone how he did it," Walker reports. "It was observed to him that the place appeared to be dreadfully crowded and it was feared there was not sufficient depth. 'Well,' observed the man. 'We can just give a covering to the body'."

As a medical man, Walker was outraged to see St Saviour's parish finances put before its inhabitants' lives like this. He was equally disgusted by the state of non-conformist burial grounds in St Saviour's, including both the Quakers' graveyard in Ewer Street and the Congregationalists' ground (a former plague pit) in Deadman's Place. Both sites, he said, were "literally surcharged with dead" and "present a repulsive aspect". Walker also reports a conversation with one Southwark gravedigger - he doesn't say from which particular ground - who admitted that new corpses could be buried in his graveyard only through "management" of those already interred. When asked what this management consisted of, the man became evasive. "He replied he would be a fool to tell anyone how he did it," Walker reports. "It was observed to him that the place appeared to be dreadfully crowded and it was feared there was not sufficient depth. 'Well,' observed the man. 'We can just give a covering to the body'."

Valentine Haycock, another Borough gravedigger, gave evidence to a Parliamentary Committee on the health of Britain's towns in 1847, where MPs asked him how his team had managed to cram 20,000 coffins into the bare acre of land at their disposal. "We dig ten feet and if we can get 12 feet we do," Haycock replied. "And then we pile them up, one upon another, as many as the grave will hold, perhaps six or eight or nine in it. Then, when that is full, we dig another grave close by the side of it and put another nine or ten in there. They are piled one on another, just as if you were piling up bricks." (163)

Haycock also told MPs that the worst moments of his job came when his shovel accidentally pierced the lid of an old coffin, releasing a stench which, he said, was "dreadful beyond all smells". In cases like that, he said, he was forced to clamber desperately back to the surface as best he could, fearing that his own death might come at any moment. "He told me that his eyes struck fire, his brain seemed a whirl and that he vomited large quantities of blood," Walker writes. "This man deserved a better fate." (164)

Walker tells us Haycock worked at "Martin's ground in the Kent Road", by which I think he means New Bunhill Fields, now the site of the Globe Academy school in Southwark's Harper Road. The surnames of the two men who owned this non-conformist burial ground just off the New Kent Road were Martin and Hoole. Haycock testified to MPs that Hoole had also rented out space in the site's bone vault, where bodies could be stacked for six months in return for a fee. He didn't say what Hoole did with the bodies when the six months was up, but the clear implication was that any flesh not dissolved by a good scattering of quicklime in the vault would simply be thrown into a quiet corner of the graveyard itself to fester on the surface.

A London newspaper got hold of this story, reporting that Hoole's vault was "over the shoes in human corruption" - meaning the slosh of half-liquidised human flesh there was deep enough to lap your ankles when you stepped inside. In his public lectures, Walker would delight in telling people about Hoole's panicked reaction: "The fear of the press inspired him with a sudden desire to set his house in order. He came in from the country, worked in his shirt sleeves at the piles of decaying matter heaped up in the vault, went home ill and died in a few days." (165)

London's cholera deaths reached epidemic levels again in 1848 and, once again, it was Southwark which bore the brunt. The Irish potato famine which began in 1845 had brought even more poor immigrants to the Borough, where David Green's figures show 43% of the housing was now in the slum category. "Middle-class ratepayers - and there were a declining number of those in Southwark - often chose to move elsewhere, especially to the new suburbs that were increasingly linked by public transport to the central districts, leaving behind an increasingly impoverished population that came to depend in ever-greater numbers on hand-outs and poor relief," he writes. Board of Health statistics from this time show that cholera caused 19 deaths per thousand people in Southwark during the 1848/49 outbreak, and that's nearly six times the rate in more prosperous areas across the river.

Often, it was the disgusting state of Borough drinking water to blame. The two suppliers in this part of London were the Southwark & Vauxhall Waterworks Company and the Lambeth Waterworks Company, both of which took their intake directly from the most heavily polluted stretch of the Thames as it flowed through London. Huge amounts of raw human sewage and all kinds of untreated industrial waste were dumped in the Thames near these intake pipes every day and the suppliers' only means of removing it before human consumption was to insert a few mesh filters in their pipes. In 1850, the doctor/scientist Arthur Hassall published the results of his microscope studies of London water, concluding that Southwark's supply was "in the worst condition in which it is possible to conceive any water to be" and "the most disgusting which I have ever examined". Lambeth Waterworks Company responded by shifting its intake pipe upstream to a cleaner stretch of the Thames, but the Southwark & Vauxhall company couldn't be bothered. (166-168)

Southwark's graveyards made their own contribution to befouling the Borough's water too. "The subsoil of Southwark has always been porous, being made of earth, sand and gravel," the former health officer William Rendle writes in his 1878 memoir. "The effect is a more or less free passage for the contents of burial places, cesspools and the like to wells in the vicinity." Back in the 1850s, Rendle adds, he'd personally traced "evidence of the most offensive and dangerous percolation into the drinking water."

All this evidence made it clearer by the day that the filthiest areas of Southwark must be cleaned up if the area was ever to have a chance of getting disease under control. But there was a Catch-22 at work. "Unless you close Cross Bones, St Saviour's death rates will never decline," said the health authorities. "With death rates as high as they are, closing Cross Bones is out of the question," St Saviour's replied. It was that simple paradox which kept the two sides at war for 20 years.

On August 13, 1849, England's newly formed Board of Health forwarded two letters of complaint it had received about Cross Bones, telling St Saviour's churchwardens that, if these complaints were well-founded and immediate action not taken to correct them, the board would step in to close Cross Bones itself. The first of these two letters came from Mariane Gwilt, who lived with her husband George in one of the Union Street schoolhouses protruding into Cross Bones' land and her remarks are worth quoting at some length:

"From the windows of the room called the school room, we have all this sickly Summer almost daily witnessed the most distressing sights. In the bone house with its open grating, which is not more than eight or ten yards from five of our windows, we have had sometimes from three to nine bodies lying in their shells for as many as ten days. (169)

"One of those shells contained the body of a woman brought here supposed dead from cholera. The sawdust and shavings saturated with blood which washed out of the shell when the body was transferred to [its] permanent coffin was spread under our windows and is there now although this occurred three weeks ago.

"On another occasion three or four weeks since, the body of a man who had drowned himself at Blackfriars Bridge was brought down here and allowed to lie in its shell ten days. Whilst he laid there, the bodies of two children who had died of the cholera were left in the dead house the chief of the time. Then the [suicide's] body was washed with a mop and pailfuls of water, the shell again washed out and all the filthy liquid, shavings and grass thrown under our windows. His clothes lie there at this time I am writing.

"Several medical gentlemen have averred to me that this burial place is dangerous to the health of this densely-populated neighbourhood. Our kitchen on the ground floor, with the school room over it, forms the wing which looks into this burial ground - the earth of which now comes at least four feet above the level of the said kitchen floor due to the number of burials which take place. This house and premises being my husband's freehold, he seems quite resolved to live and die here notwithstanding.

"We are now both of us considerably advanced in years and my health has suffered materially these last five years. I have no doubt the impure air from this pestiferous locale injures the health also of the surrounding vicinity and earnestly hope that the remedy will at once be obtained." (170)

St Saviour's churchwardens wrote a feisty response to this letter, kicking it off with a heavy hint to the board that Mrs Gwilt was a malicious cow whose evidence shouldn't be trusted for a moment. They didn't put it quite like that, of course, saying instead that "it is to be hoped" her "many erroneous statements" had arisen merely from "some misapprehension or misinformation" on her part. They went on to claim Cross Bones sometimes went as long as six days without a single interment there and told the Board this was the first they'd heard of any complaints. Then they turned to Mrs Gwilt's specific points:

* "That the distance of the bone house is not great from Mrs Gwilt's windows has arisen from Mr Gwilt having built over the Common Sewer adjoining to the burial ground," the wardens wrote. "[This] may be considered an encroachment on the burial ground - and no burials have taken place during the last eight years at a distance nearer to such rooms than 50 feet."

* In reply to Mrs Gwilt's charge that up to nine bodies had lain unburied in the bone house for as long as ten days, St Saviour's sent the board an extract from its bone house register. This listed seven people consigned there in the 20 days before Mrs Gwilt wrote her letter, the longest unburied of whom remained above ground for three days. He was Charles Shooter, the Blackfriars Bridge suicide, who St Saviour's said could not be buried straight away because of a delay in the coroner's inquest. (171, 172)

* If the bodies Mrs Gwilt complained about had not been moved to St Saviour's, the wardens continued, they would instead have remained in the family's cramped living quarters until burial. "The [parish] officers have thought it most dangerous to let the bodies remain among the living, occasioning the spread of disease and therefore directed the body to be taken to the bone house," they wrote.

* "With respect to the lady's statement about straw and shavings, she is equally erroneous - straw and shavings being used only by the men upon their shoulders when carrying the shells. If any shavings etc have been allowed to remain in the burial ground, it has been from inadvertence."

* "Mrs Gwilt is also under error as to the cleansing of the bodies by mops and pailfuls of water, the Beadle only using the same for cleansing of the bone house. The Beadle has been compelled to preserve the clothes of the persons found drowned in order that they should be owned and delivered up. No other course is open to him."

In my view, this exchange emerges as something like a draw. The churchwardens' subtle undermining of Mrs Gwilt's character ("it is to be hoped"), combined with her family's decision to build over Cross Bones without permission, hint that a feud between the two sides was already well underway when she put pen to paper. If so, that history would account for a degree of rhetoric in her letter which may not always match the facts. On the other hand, St Saviour's often resorts to technicalities rather than substance in responding to her points. Mrs Gwilt was never suggesting the bodies awaiting burial at Cross Bones should have been left in people's homes instead, for example - merely that she wished they could be buried a bit more promptly once they'd arrived on her doorstep. Not was she urging St Saviour's to throw Charles Shooter's clothes away, but simply to find somewhere better they could be stored. (173)

In my view, this exchange emerges as something like a draw. The churchwardens' subtle undermining of Mrs Gwilt's character ("it is to be hoped"), combined with her family's decision to build over Cross Bones without permission, hint that a feud between the two sides was already well underway when she put pen to paper. If so, that history would account for a degree of rhetoric in her letter which may not always match the facts. On the other hand, St Saviour's often resorts to technicalities rather than substance in responding to her points. Mrs Gwilt was never suggesting the bodies awaiting burial at Cross Bones should have been left in people's homes instead, for example - merely that she wished they could be buried a bit more promptly once they'd arrived on her doorstep. Not was she urging St Saviour's to throw Charles Shooter's clothes away, but simply to find somewhere better they could be stored. (173)

St Saviour's was equally defiant in tackling the board's second complaint, this one from a Dr Lever:

"Cholera has prevailed in this vicinity to a fearful extent. The Parochial Officers have been told of the danger incurred by their continuing to inter in the ground [but] still they will not discontinue, as they are afraid of losing their fees.

"Upwards of 12 months since, the late Mr Callaway and myself signed a requisition as professional men, begging the churchwardens that no more burials might be permitted. To this requisition were appended the names of nearly every respectable inhabitant whose house is near the [graveyard], but the parish officers turned a deaf ear." (96)

St Saviour's replied that Cross Bones was "as well situate, as little offensive to health and public morals and as open as almost any ground in the Metropolis. From these facts, we are of the opinion that the burial grounds of this parish are not in a state to require special interference of the Board of Health."

Edwin Chadwick, the same man we met at the 1841 enquiry into urban burial grounds, was now heading the Board of Health - and he didn't agree with St Saviour's complacent view. On September 14, 1849, less than a month after the parish had responded to Gwilt's and Lever's complaints, The London Gazette's front page carried an official board announcement. Addressed to the St Saviour's churchwardens as a kind of open letter, it began by reminding them of the board's powers to inspect British burial grounds and demand action on any it found to be dangerous. The board's own inspector had now surveyed Cross Bones for himself, it said and pronounced it a health hazard to anyone living nearby. Therefore, the board was ordering St Saviour's to stop burying people there immediately and not to resume doing so without its express permission. (174)

You'd have thought that would be the end of the matter, but still St Saviour's fought on. It replied that closing Cross Bones "would entail a serious inconvenience and great additional expense to the poorest inhabitants of this parish", arguing that the board's verdict was based "chiefly if not wholly on the false and exaggerated statements contained in a letter of Mrs Gwilt". When the board issued a legal summons against St Saviour's for failing to obey its closure order, the parish consulted its own lawyers and concluded the board had exceeded its powers by ordering Cross Bones' outright closure in the first place. (175)

Perhaps that's why the board's next ruling took a slightly different line. On October 16, it had The London Gazette carry another nessage to St Saviour's, this one preceded by an even longer list of the board's statutory powers. It then demanded that all the following changes must be made at Cross Bones before any further burials were considered:

* Entire surface (barring footpaths and any paved areas) to be covered with at least three inches depth of quicklime.

* Where this quicklime was disturbed for the purpose of digging a new grave, it must be replaced to a depth of three inches as soon as that grave was re-filled.

* All new graves on the site to be coated with at least three inches of quicklime at the bottom before the coffin goes in.

* One coffin per grave. No exceptions.

* All graves to be at least two feet six inches apart.

* All coffins to have at least five feet of dirt between the lid and surface ground

* All coffins placed in vaults, brick-lined graves or catacombs on-site to be lined with lead and soldered air-tight.

* If any bones or coffin parts should be unearthed, the earth disturbed must be replaced immediately and an extra three inches of quicklime deposited on that spot.

* No ground to be disturbed, or any new grave dug, on a spot where a burial's been made in the past ten years.

By this point in its long history, I doubt there was a single inch of Cross Bones where even half these conditions could be satisfied, so you could argue the list amounted to another order that the ground should simply be closed down. By going through the formality of setting out necessary changes in this way, I imagine the board was simply ensuring it hobbled any legal challenge St Saviour's may care to launch in future.

On October 22, 1849, St Saviour's vestry met again to hear the latest report form its Cross Bones committee. "The chairman reported that the Cross Bones ground had been cleaned up and a new path laid," the MoL says. "It was found that the old path had no bodies under it and 'would afford ample accommodation for the wants of the poorer inhabitants for a long time to come'." We know St Saviour's approached the Board of Health after this meeting, asking if it could use the area under the old path alone for new burials, but not what the board said in reply. One way or another, though, as the MoL confirms, burials certainly did continue at Cross Bones well into the 1850s and there's good reason to believe nothing much changed in how the site was run.

As evidence for this, we have a November 1852 letter to Spencer Walpole, Britain's Home Secretary, from a group of residents in Union Street, Borough High Street and Redcross Way. All those streets lined the walls of Cross Bones, so people living there had more opportunity than most to observe what went on at the site and every reason to fear its effect on their health. Here's what they told the Home Secretary:

"The gravedigger is daily seen with a long steel-pointed iron rod, sticking the ground here and there, spearing the top coffins until some wood gives way, whereupon the whole of the contents, sometimes many [coffins] in that particular grave, are turned out and remain several days above ground to the scandal of all Christian men. When each of these exhumations have taken place, there have been seen in such human remains a number of skulls too numerous to mention, lying like half-devoured turnips about a sheepfold and cared for as little." 96, 176)

The letter added that between ten and 13 people living at one of the underclass lodging houses in Redcross Way had died during a single month of the 1849 cholera outbreak and reminded Walpole that the Board of Health's closure order against Cross Bones had been allowed to go unenforced. "There has been no cessation in these scandalous outrages on the dead, nor the least abatement of the sickening and abominable effluvium emanating from this enormous heap of putrescence," it concludes. "We pray, Right Honourable Sir, and rely upon your kind interference to prevent the continuance of this great and most abominable nuisance to the safety of our families and the comfort of our homes."

Walpole responded by commissioning his own inspection of Cross Bones, this one carried out by a Dr Sutherland. The report he submitted to Walpole did not make happy reading:

"[Cross Bones] is evidently used for an inferior class of interments and can be considered only as a convenient place for getting rid of the dead. It bears no marks of ever having been set apart as a place of Christian Sepulchre. It is crowded with dead and many fragments of decayed bones, some even entire, are mixed up with the earth of the mounds over the graves."

Sutherland's figures show that a total of 1,180 bodies were buried in Cross Bones' total area of 2,089 square yards between 1845 and 1851 alone, with the cholera years of 1849 and 1850 bringing the highest loads. "If proper regulations had been adopted for this ground and 39 superficial feet allowed for each interment, which is the average required to protect the public health from injury, the whole area would have accommodated only 482 coffins, [and] it would have been full in somewhat less than three years," Sutherland writes. His figures demonstrate that even if Cross Bones had been completely empty in 1845 - which it certainly wasn't - it would have already been packed with more than twice the number of dead it could safely carry by the end of 1850.

Sutherland's figures show that a total of 1,180 bodies were buried in Cross Bones' total area of 2,089 square yards between 1845 and 1851 alone, with the cholera years of 1849 and 1850 bringing the highest loads. "If proper regulations had been adopted for this ground and 39 superficial feet allowed for each interment, which is the average required to protect the public health from injury, the whole area would have accommodated only 482 coffins, [and] it would have been full in somewhat less than three years," Sutherland writes. His figures demonstrate that even if Cross Bones had been completely empty in 1845 - which it certainly wasn't - it would have already been packed with more than twice the number of dead it could safely carry by the end of 1850.

Burials at the College Ground had been abandoned by the time Sutherland inspected Cross Bones, leaving St Saviour's with just two parish grounds at its disposal: Cross Bones and the churchyard surrounding what's now Southwark Cathedral. Between the two, these gave St Saviour's a total burial area of just 3,583 square yards to serve a population of about 19,638. "The parish is a very unhealthy one and has an annual mortality of above 29 in the 1,000, [so] the annual deaths are 550," Sutherland continues. "Were the two grounds now opened for the first time and were all the parochial dead buried in them, they would be entirely filled in about 18 months." (177)

His conclusions were these:

* Burial ground provided in St Saviour's parish was "entirely inadequate to the wants of the population"

* Both St Saviour's remaining parish grounds had "long been completely overcharged with dead".

* Further burials at either of these grounds would be "inconsistent with a due regard for the public health and public safety".

* Burials at both Cross Bones and St Saviour's churchyard "should be wholly discontinued".

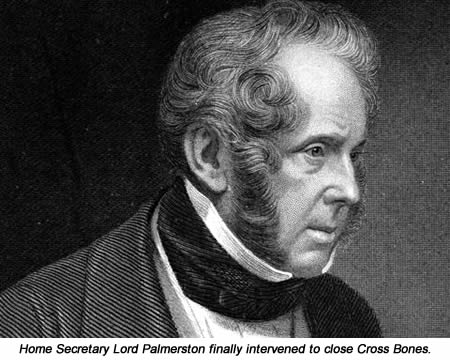

"This time the vestry was forced to act," the MoL says. "On 29 March 1853, the burial board reported, that after looking at alternative locations for burial, including parish land at Sydenham, the best solution was to approach one of the cemetery companies. This led to the offer of a piece of ground of between six and seven acres in the cemetery at Brookwood, near Woking, belonging to the London Necropolis Company." Four month's later, Lord Palmerston, Walpole's replacement as Home Secretary, ordered that Cross Bones must close no later than September 21, 1853. He rejected St Saviour's plea for a week's stay of execution while the LNC deal was finalised, forcing the vestry to make interim arrangements with the Victoria Park Cemetery Company in Hackney instead. (178, 179)

St Saviour's vestry minutes include a note made on October 24, 1853, confirming that Cross Bones was now closed for good. In a letter to The Times 30 years later, Lord Brabazon, a campaigner for urban parks, claimed the last Cross Bones burials of all were those of Sarah Fleming, aged 36, who'd lived at St Margaret's Court in the Borough and a child named Sawday from Redcross Way itself. He dates these two final burials to October 31, 1853, but doesn't explain how this can be made to square with the other information available.

By November 1854, St Saviour's was ready to end its temporary arrangement with Victoria Park and switch to the ten acres it had leased at LNC's Woking cemetery instead. The parish charged 14 shillings for each adult funeral it arranged through LNC and 10 shillings for every child's funeral. This covered road transportation to LNC's Waterloo depot, one-way train passage for the body to Woking, two third-class return tickets for the mourners, plus minister and gravedigger's fees. St Saviour's added an extra shilling to the price if burial in consecrated ground was required, plus two shillings for every additional mourner who wanted to go along. LNC's own third-class fares at about this time were set at two shillings (single) for every corpse and two shillings and sixpence (return) for each mourner, so all the ancillary services would have left St Saviour's little, if any, profit. Pauper funerals, of course, brought in no money at all and we have figures showing St Saviour's paid for 89 of these at Brookwood in 1858 alone.

Left with an inner-city graveyard it could no longer use, St Saviour's rented out Cross Bones to a Mr Stephens, who signed a 26½-year lease on the site in November 1854 at annual rent of £50. Stephens promptly sub-let the site to a local tradesman called Downs, who used it as a builder's yard. A good deal of work would have been needed to get Cross Bones in shape for any commercial use like this, but when that work was done and who paid for it I don't know.

In 1868, the Bishop of Winchester's rights to the old Clink Liberty's land were formally transferred to the Church of England's Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who duly passed Cross Bones' freehold on to St Saviour's parish. Given full ownership of the site at last, the churchwardens there waited till Stephens' lease completed its term in 1881, obtained the necessary Home Office development licences and offered Cross Bones as building land instead. This prompted an immediate protest from Lord Brabazon, who accused St Saviour's of desecrating Cross Bones merely to maximise its financial return. He quickly sketched out the site's history in a November 1883 letter to The Times and then issued this call for action:

"The ground is now being offered to the public, on lease, as an 'eligible building site'. It is with a view to save this ground from such desecration and to retain it as an open space for the use and enjoyment of the people, that I now address you.

"The trustees have under their consideration an application from a builder to acquire this ground for building purposes at a rental of £200 and at a meeting of the trustees held on [November 7], it was stated that, unless somebody came forward to purchase this space as a public garden, so that the dead might yet remain in peace, the trustees would be forced to let it for building purposes.

"The person making the offer has obtained the sanction of the Home Office, providing that he undertakes to excavate the ground to the level of the virgin soil and to remove all human remains. This he is apparently willing to do, but how it is likely to be done may be inferred from what happened in a similar case, where cartloads of earth mixed with human remains were seen leaving the ground for sale as garden soil.

"It is to be hoped the public will take this matter up and raise a sum - say, £6,000 - for [the site's] purchase to be maintained as an open space for the perpetual use and enjoyment of the people. This neighbourhood abounds in narrow courts and alleys, filled with the poor of both sexes, far removed from any open space." (170)

Brabazon followed up this letter with a second one to The Times a few weeks later, saying St Saviour's was keen to maximise its income from Cross Bones now only because a recent change in legislation had abolished the church-rate payments it previously received. The builder mentioned in his first letter, he added, was already drilling exploratory holes at Cross Bones to assess the amount of work need to clear the site of human remains and hence decide what final price he was prepared to offer. His plan was to erect "a block of industrial dwellings" on the site. (180)

In the end, it was not the prospect of this extra work which saved Cross Bones from the 1883 development deal, but Parliament's passing of 1884's Disused Burial Grounds Act, which made it illegal to build anything but a place of worship on any old burial ground. That legislation has been considerably weakened since, so it can't help Cross Bones now, but in the aftermath of Brabazon's letter it was enough to kibosh the whole deal. "The only thing that you could do with a piece of ground that had previously been used as a graveyard was build a church on it," Dark told me. "And you don't need a church there."

Returning to the option of short-term leases on the site, St Saviour's let it out to Charles Hart, a showman, who set up a full steam-driven fairground at Cross Bones in 1892. His nightly attractions there included shooting ranges, steam roundabouts and a notoriously nerve-wracking new ride called the Razzle Dazzle. But residents nearby complained of the noise and Hart's fairground was closed down as a nuisance.

By 1929, the area's collective memory had faded enough for developers to assume any human remains at Cross Bones must have been removed long ago and another team of constructors excavating there were surprised to find themselves turning up human skulls. "A number of human remains was unearthed, skulls and limb bones predominating," the Borough's Medical Officer Horace Wilson wrote in his annual report. "They were found six feet below the surface and descended to a depth of ten feet. These bones were of considerable antiquity."

Wilson goes on to say that these particular bones were reburied at the LNC's ground in Brookwood, but that's no guarantee that the construction gang at Cross Bones was equally meticulous throughout the whole project. I wonder if their 1929 work went on to build the warehouse foundations the MoL found lined with bones in its own dig 64 years later? (97)