“Listening in”, as radio fans called their hobby, was far from the casual business which transistors and DAB allow today. Most listeners received the BBC on their £3 crystal sets, teasing a fragile signal through the headphones required and shushing other members of the family at every tiny interruption. Programming then consisted of Reuters' strictly-policed news summary, classical concerts and several thousand live BBC talks every year. This was supplemented by live dance bands from the Savoy Hotel and whatever innovations managing director John Reith could get past the authorities.

“Listening in”, as radio fans called their hobby, was far from the casual business which transistors and DAB allow today. Most listeners received the BBC on their £3 crystal sets, teasing a fragile signal through the headphones required and shushing other members of the family at every tiny interruption. Programming then consisted of Reuters' strictly-policed news summary, classical concerts and several thousand live BBC talks every year. This was supplemented by live dance bands from the Savoy Hotel and whatever innovations managing director John Reith could get past the authorities.

Reith's efforts encouraged growing affection for the BBC, and gradually it began to take a place at the very centre of British public life. In 1923, Reith persuaded Parliament to let him broadcast Big Ben's chimes for the first time. In April 1924, King George V allowed his speech opening the British Empire Exhibition to be broadcast live. Large public speakers were placed along London's busy Oxford Street, and drivers there pulled over to hear him speak. The first purpose-built radio play, complete with sound effects, went out later that year.

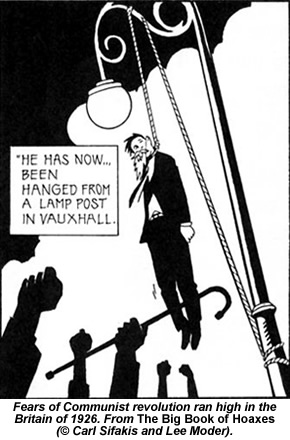

Still there was considerable nervousness where BBC news was concerned - not least among Reith's own staff. The Reuters deal meant the BBC had to take this news agency copy as it had been written, and had no direct control over its content. One 1924 Reuters summary revealed that Princess Mary's babies were attended by two nurses, and that the younger child was carried about on a white silk cushion. “This information only helps to stimulate feelings akin to Bolshevism,” BBC director of programmes Arthur Burrows complained. And there's that fear of a Communist uprising again.

Reith himself was always braver about these issues. In one Radio Times column, he recalled a 1923 BBC debate which had dared to include a Communist on its panel. “It produced not revolution, but an interesting discussion,” Reith assured his readers. (11)

Still the Post Office seemed determined to block Reith at every turn, refusing his requests to broadcast even the most carefully-balanced political debates or any speech emanating from Parliament. Reith kept firing away, suggesting ideas like broadcasting the Memorial Day service at the Cenotaph or the Oxford Union's debates, but was almost always turned down flat or expertly stalled. Finally, the frustration started to show. “We urgently need to develop new lines and keep opening new fields,” he told the Postmaster General in one exasperated 1925 letter. “The service is being badly prejudiced.”

As that year drew to a close, the BBC had an audience of over ten million people, and the technology to reach 30 million more. The Government's Sykes Committee would soon recommend that “a modicum of controversy” be allowed on the BBC - a move the Postmaster General ultimately had to accept - but Ronald Knox already had something far more ambitious in mind.

It all looks so innocent in The Times' daily radio listings: “7;40: - The Rev. Father Ronald Knox - 'Broadcasting the Barricades', SB from Edinburgh.”

Even there, though, there is a small clue to be uncovered. The broadcast itself, as we'll see in a moment, gave a distinct impression that it was coming from London and that the announcer was speaking from the very building invaded by rioters at his report's conclusion. In fact, the announcer - played by Knox himself - was sitting in Edinburgh. Knox knew George Marshall, the BBC's station controller at Edinburgh well, was accustomed to working with him, and found his the most convenient BBC studio to use.

No recording of the broadcast survives, but we do have Knox's original 17-minute script from the BBC archives, and Evelyn Waugh's account from his 1959 biography of Knox. Before the programme began, Marshall delivered a short announcement telling listeners' exactly what they were about to hear.

“It was prefaced by an explicit statement that it was a work of humour and imagination, enlivened by realistic ‘sound effects’, which were still a novelty,” Waugh explains. “Read today, it seems barely credible that it could have caused a tremor of alarm in the most timid listener. (Ronald) had no idea of imposing on anyone. The intention was broad parody.” (9)

Marshall's announcement gave way to a moment of deliberate static, and then Knox's voice imitating a lisping, elderly don in mid-lecture. This character - who Knox christened William Donkinson - concludes his remarks by mentioning “litewawy valuth and a higher thenthe of the poththibilitieth of human achievement”, gives a prolonged cough, and then lapses into silence.

Like the faked news report that followed, Donkinson's contribution was written to copy the BBC's prevailing style, but to exaggerate all that style's distinguishing marks to the point of parody. BBC listeners at the time would have been well-used to hearing improving educational talks on the wireless, often delivered by academics who were only a little less eccentric than Donkinson seemed to be. Knox also took care to copy BBC style when composing his news copy, adding the extra element of deliberate confusion as fresh reports seemed to arrive on the announcer's desk or the story's unpredictable nature forced the BBC to cut in and out of its Savoy dance band transmission.

“The idea for this skit came to me while I was sitting at home listening to the results of the last election being broadcast,” Knox later explained. “I endeavoured to visualise the breathlessness there would be throughout the country during a revolution, and I tried to imagine the news bulletins during such a time of popular excitement. I put my ideas on paper and then attempted to burlesque them.” (12)

The resulting script is peppered with stylistic tics and outright jokes, which Knox evidently assumed would alert his listeners not to take it too seriously. I've rigorously excised all those jokes from the account of the broadcast opening this piece to try and duplicate the sensationalist impression most listeners seem to have taken away. But just look at the tip-offs they missed:

* Knox uses comedy names for all the characters mentioned in his report: Mr Popplebury, Sir Theophilus Gooch, Miss Joy Gush and Mr Wotherspoon. Any one of these names may be thought ridiculous enough, but taken together, they're a clear indication that something fishy's going on.