This is the earliest evidence we have that the song now incorporated Tom's near-escape and capture into its narrative. Given the singer's family ties with the man responsible for that capture, I'm content to assume it was Gilliam Grayson who ensured that verse was included on the recording. Why should Uncle James be left out?

This is the earliest evidence we have that the song now incorporated Tom's near-escape and capture into its narrative. Given the singer's family ties with the man responsible for that capture, I'm content to assume it was Gilliam Grayson who ensured that verse was included on the recording. Why should Uncle James be left out?

What little music radio there was in 1928 seems to have passed Grayson & Whitter's disc by. In its way, that's a blessing because their version's continuing obscurity allowed many rival sets of Tom Dooley's lyrics to keep developing alongside it. Unlike, say, Arthur Tanner's 1925 recording of Knoxville Girl, it never set a single version of the song's tale in stone, driving all variations to the margin.

In Tom Dooley's case, that process would have to wait for another 30 years and, by the time the Kingston Trio came along, the song's many variants were established enough to survive their sudden demotion to also-ran status. They may not have been able to compete with the Trio version's success, but they weren't erased by it either.

One such variation was collected from a North Carolina woman called Franklin in 1930, who told the song collector Mellinger Henry she'd learned it from her brother. Later reprinted in the Viking Book of Folk Ballads, it includes the verses:

"I had my trial in Wilkesboro,

Oh what do you reckon they done?

They bound me over to Statesville,

And that's where I'll be hung."

[...]

"Oh what my mammy told me,

Is about to come to pass,

That drinking and the women,

Would be my ruin at last." (15)

The first of these two verses appears in recordings by both Sheila Clark in 1986, and the Great America String Band in 2005. The tone of voice it's written and delivered in always suggests that the move to Statesville was another crafty trick to persecute Tom, when in fact it represented Vance's best chance of saving him. Having said that, though, the verse does immortalise one aspect of Tom's story that's mentioned in no other lyric, and it's well worth having for that reason alone.

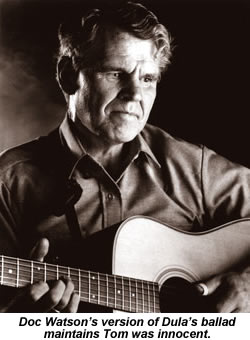

Doc Watson would have been about seven years old when Henry collected those verses, and perhaps already familiar with the Tom Dula song his grandmother sang. Doc, or Arthel as he'd been christened, was born in 1923 on his poor parents' Watauga County farm and blinded by an eye infection before he was two. Even so, he soon turned out to be the most talented member of what was already a very musical family, playing the harmonica as a child, adding banjo and guitar by the age of 12, and making his first recordings as a member of Clarence Ashley's backing band in 1961. His own debut album followed three years later, and he went on to win eight Grammy awards.

Watson put his own version of Tom Dooley to disc on that 1964 debut, assuring live audiences that it was "a completely different version" to the Kingston Trio's hit. It's a rollicking great party of a record, led by Doc's busy, swooping harmonica and driven relentlessly forward with barely a breath between one line and the next. "Many people think that the original version, which I learned from my grandmother, has such a lilting, happy-sounding tune because the composer had tried his best to get a little of Tom Dooley's personality as a fiddler into the song," Watson later wrote.

Clearly drawing on the same sources Grayson & Whitter used, he sings six of the same verses they gave us. But he also adds two fresh verses of his own:

"Trouble always trouble,

A-rolling through my breast,

As long as I'm a-living boys,

They ain't-a gonna let me rest.

"I know they're going to hang me,

Tomorrow I'll be dead,

Though I never even harmed a hair,

On poor little Laura's head." (16)

This is the song's most trenchant insistence on Tom's innocence yet, and it's based on the fact that he really did declare his innocence on the gallows. By the time the folk process was through with his 60-minute speech there, the moment had been boiled down to Tom holding out a steady hand to the watching crowd and saying: "Gentlemen, do you see this hand? Do you see it tremble? Do you see it shake? I never hurt a hair on the girl's head".

What we know now, of course, is that before even leaving his cell, Tom had confessed sole responsibility for the murder. Many people in Tom's home state still like to believe he was innocent though, and it may be no coincidence that the only modern bands I've been able to find using these particular verses are The Elkville String Band and The Carolina Chocolate Drops.

"In the 1860s, my great-grandparents were neighbours of Tom Dooley's family," Watson wrote in 1971. "And my grandparents, when they were just children, knew Tom's parents. As the story goes, Tom Dooley was not guilty of the murder of Laura Foster, although he was an accomplice in covering up the crime. [.] Almost everyone around affirmed that Annie Melton had stick the knife in Miss Laurie's ribs, and then hit her over the head. Tom Dooley, however, actually buried the girl." (17)

Watson's family tales went on to insist that Grayson was the sheriff who arrested Tom, that he did so because he loved Ann himself and that he eventually married her, hearing her deathbed confession years later and then moving back to Tennessee in disgust. There's so much wrong with that account that I hardly know where to begin, but I think my favourite part is the desperate addendum required to get Grayson packed off back to his real home state before the whole yarn disintegrates.

Doc Watson wasn't the only Watauga County man to have a grandmother tied up in the Dula story, nor to learn his first version of the ballad from her. Frank Proffitt had a granny on the scene too, and it's her role in the tale which ultimately gave The Kingston Trio its hit.

According to the family legend that later built up around her, Adeline Perdue was watching in the Statesville crowd as Tom's cart drew past her on its way to the gallows. Telling the story to her children, she described Tom sitting upright in his own coffin, singing the autobiographical ballad he'd just composed. Perdue taught that song to her family, and it eventually made its way down to her grandson Frank.