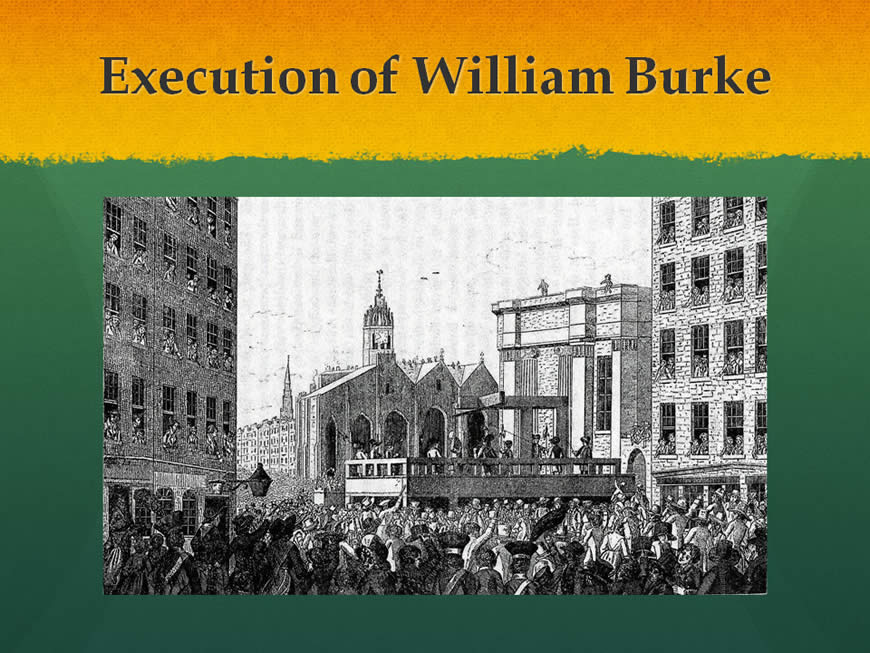

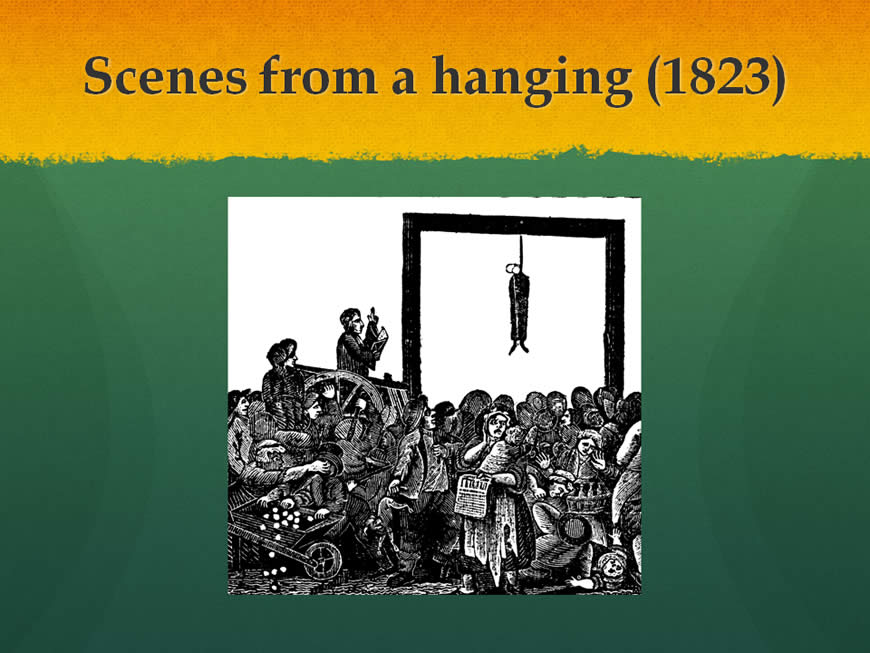

On January 28, 1829, a crowd of over 25,000 people gathered in Edinburgh's Lawnmarket to see William Burke hanged. As this eye-witness print shows, they packed every inch of the streets round the gallows platform. Any householder with a view of the site had people begging to rent a viewing spot at one of his windows, and found he could charge a guinea or more for every spot available. That's worth about £100 in today's money.

Everyone wanted to be there to see Burke die. And they wanted to see him suffer too.

Burke and his partner William Hare had murdered 15 Edinburgh vagrants over the past 18 months, but it was not this which caused such an outpouring of hatred towards them. It was the fact that they'd sold all those corpses to the surgeon Robert Knox for dissection in his anatomy lectures. Most people viewed the whole process of dissection with enormous disquiet in 1829, and it was that aspect of his crimes which made so many people keen to see Burke hang.

It was we might call a celebrity execution.

The atmosphere that day was half rock festival, half riot - as this eye-witness account confirms:

"At every struggle the wretch made when suspended, a most rapturous shout was raised by the multitude. When the body was cut down, at three-quarters past eight, the most frightful yell we ever heard was raised by the indignant populace, who manifested their most eager desire to get the monster's carcass within their clutches and gratify their revenge by tearing it to pieces."

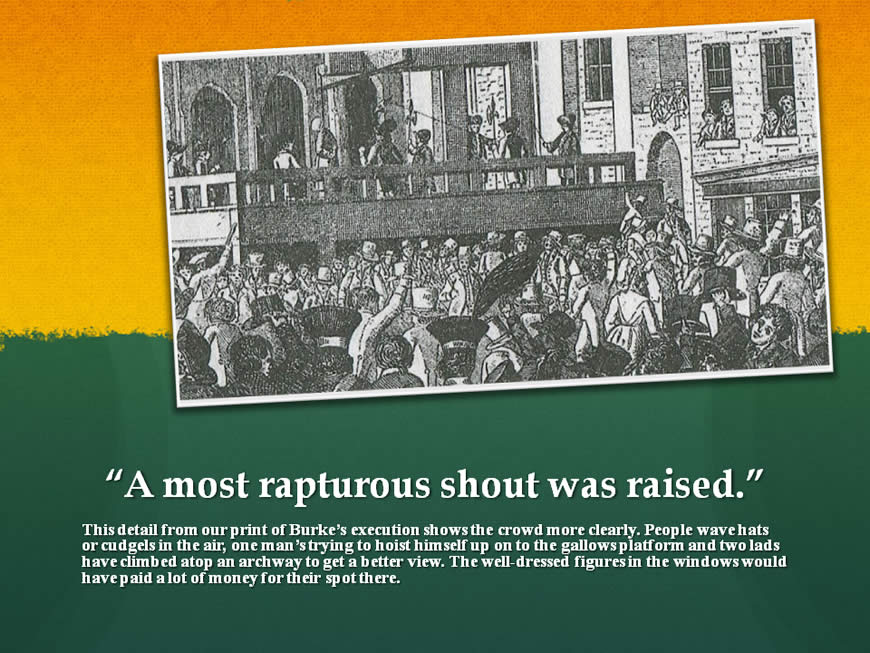

As I said: a mixture of a rock festival and a riot. The people attending big public executions like Burke's were in party mood, often drunk, and few behaved with any decorum. Prostitutes and pickpockets would work the outskirts of the crowd, as hawkers offering food or booze cried their wares. We can see the result in this detail from an 1823 print.

Reading the crowd from left to right, we can see a lady fruit vendor fighting with a man who's trying to overturn her wheelbarrow and a man preparing to hurl his dog at the hanged man. There are stories from about this time of people throwing dead dogs at offenders in the stocks, so perhaps that's what gave him the idea.

Further along, there's a woman drawing her arm back to punch someone she's got down on the ground, an innocent by-stander knocked off her feet by this brawl and a trader hawking beer bottles from her basket. And all this while the condemned man hangs dead just a few feet away, and the preacher struggles to make himself heard.

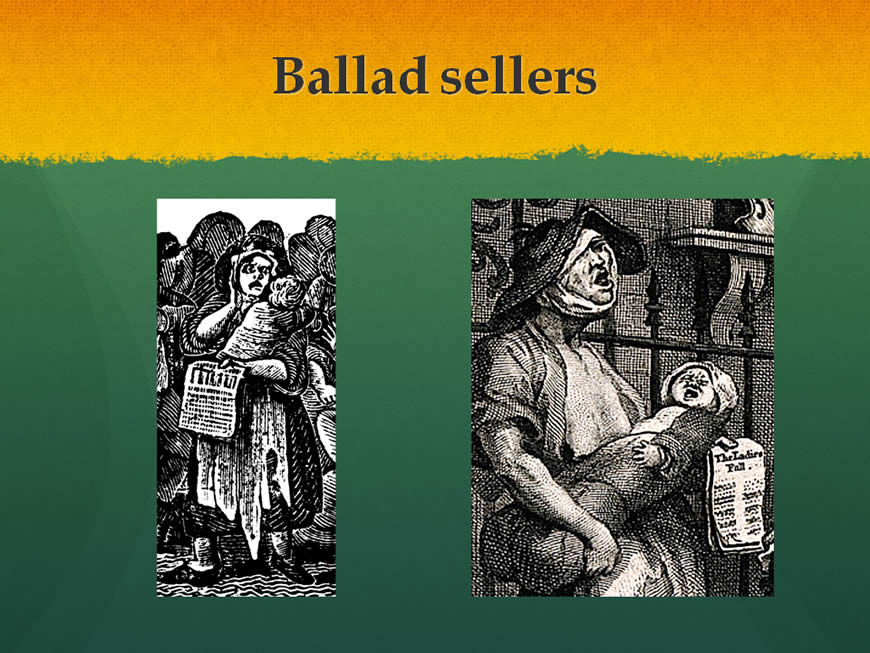

But it's the woman at the centre of this picture who's most interesting of all. Let's take a closer look at her.

. and there she is on the left. The other illustration's taken from a rather earlier print, but both these women are doing the same job. They're both ballad sellers.

They're clearly in need of money - we can tell that by the state of their ragged clothes - and hard-pressed to make a living while also caring for their children. They're crying their wares alongside all the other hawkers and traders at the hanging, and their stock in trade is that sheaf of papers each holds in her left hand - Gallows Ballad Sheets.

These were single-sheet publications, knocked out overnight by jobbing printers and sold at the foot of the scaffold while the condemned man was still dangling. Often, they'd contain a set of ballad verses, supposedly written by the killer himself, warning others not to follow his path.

So, how did these grisly publications come about?

Well, any sensational murder in the Victorian era got the same blanket coverage in their newspapers as it would get in our own. But there was a problem. For much of the 19th Century, British newspapers were subject to a heavy stamp duty, which priced them out of reach for all but the middle classes and the aristocracy.

Ballad sheet printers saw a gap in the market, and began knocking out their cheap, single-sheet publications as an affordable alternative for the working class. Ballad sheets sold for just a penny, against sixpence or more for a typical newspaper, and it was always the most lurid ones which sold best.

The poor of this era struggled to make even the most basic living. Rather than rely on the workhouse, many opted to become ballad sellers instead. They would buy a sixpenny bundle of their chosen ballad sheet from one of the print shops, then sell on the 12 or 15 copies that provided at a penny each. The ballad verses were composed to fit popular folk or hymn tunes, so ballad sellers could sing a snatch of them to pull in a crowd. Some would accompany themselves on the fiddle, or whatever other cheap, portable instrument they were able to play.

And where better to sell these sheets than at the killer's own - very public - execution?

Printers all over the UK were churning out these sheets and Edinburgh, like any big city, had its share. There was Robert Menzies in Brodie's Close, Forbes & Co in Cowgate, William Smith in Bristo Port, and a dozen others. The Burke & Hare case gave these printers a field day, and it's the ballad sheets they produced about it which I want to examine here.

All the sheets I'm looking at today are taken from the National Library of Scotland's collection, and available for study on the library's website.

Before I show you these, though, perhaps I should just canter through the core facts of Burke & Hare's spree for anyone who may not know them. Here's the unlovely pair themselves:

The demand for dead bodies in Edinburgh was created by a new way of teaching anatomy, called the Paris Method, which demanded that every student be given a corpse of his own to dissect, rather than simply watching a single lecturer do it at the front of the room. This meant a great many more cadavers were needed, but the only legal source of them within Britain was bodies from the gallows. Even with 60-odd executions a year in the UK, that supply could never hope to keep pace with the new demand, and many anatomists resorted to buying bodies from grave-robbers instead.

It's important to understand, though, that Burke & Hare themselves were not grave-robbers. The first body they sold was that of an old pensioner who died of natural causes while owing rent at the Tanner's Close boarding house Hare ran with his wife Mary. Hare recruited Burke - another tenant there - to help him recoup his losses by selling the old man's body to Knox. That was in December 1827.

Realising they were on to a good thing, Burke & Hare then turned to murder. They would choose a vulnerable figure from the streets of Edinburgh - almost always a woman - invite her back to Tanner's Close and then feed her whisky till she passed out. As soon as their victim was asleep, one or other of the men would block her nose and mouth to prevent her breathing while the other lay across her body to keep her still.

This is Burke's own description of the process:

"When we kept the mouth and nose shut a very few minutes, they could make no resistance, but would convulse and make a rumbling noise in their belly for some time. After they had ceased crying and making resistance, we left them to die."

They killed 15 people in this way and sold all the bodies to Knox, who turned a blind eye to the cadavers' origins in order to safeguard his supply.

Burke & Hare were finally caught in November 1828, by which time they had become careless enough to let one of their victim's bodies be discovered. Fearing they would not get a conviction otherwise, the authorities persuaded Hare to turn King's evidence in return for immunity. This ensured that Burke alone hanged for their crimes. Many people in Edinburgh thought that Hare - and Knox - should have died beside him.

This sensational story made headlines throughout the world, making Burke & Hare two of the most famous killers this country has even seen.

Any case of that size was sure to produce ballad sheets at every stage of its development. There would be one reporting the crime, another the killer's capture, a third detailing his trial, a fourth reporting the execution and so on. Every printer would be turning out rival sheets at each of these stages, so it was a very competitive business.

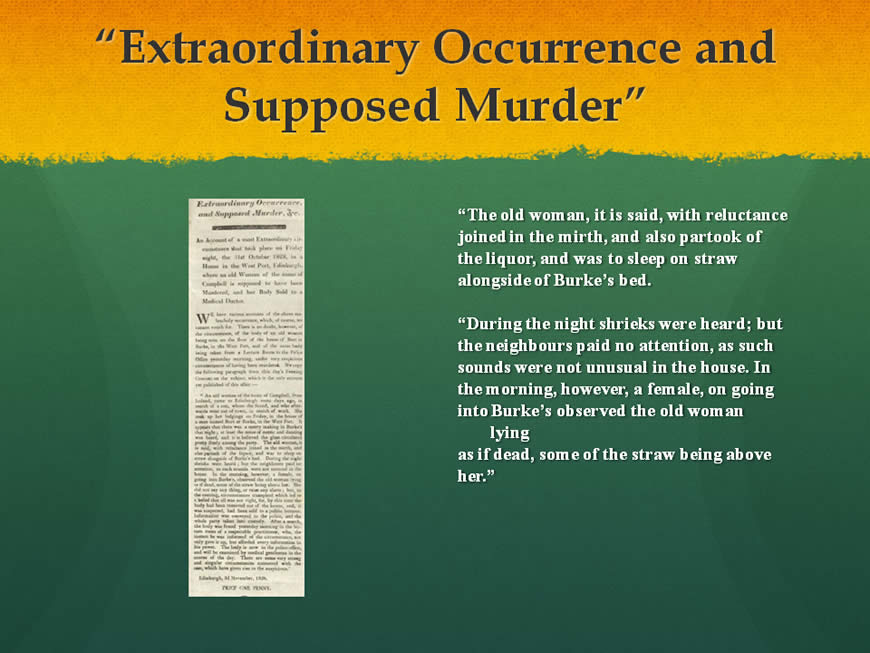

I tend to call all these publications ballad sheets as a generic term, but some didn't have ballad verses at all. Instead, they simply stole a prose account from one of the newspapers and reprinted it as a block of text. That's what's happened here, with this sheet's account of Burke & Hare's last murder - the one which finally led to their arrest.

As you can see, it's not a particularly attractive sheet to look at. But it is hot news. This sheet's dated November 3, 1828 - just a couple of days after Mary Docherty's body was discovered - and many of the facts are still unclear. At a couple of points, the account is forced to hedge its bets by saying the body was discovered "at Burt or Burke's house". They're not even sure what his name is yet, and that's a measure of how fresh this news was when the sheet first went on sale.

The text describes Docherty's last night on Earth, and her killers' half-hearted attempt to hide the body beneath a few handfuls of straw. As with all their victims, Burke & Hare took her in, then suggested they all drink some whisky together:

"The old woman, it is said, with reluctance joined in the mirth, and also partook of the liquor, and was to sleep on straw alongside of Burke's bed. During the night, shrieks were heard, but the neighbours paid no attention, as such sounds were not unusual in the house. In the morning, however, a female on going into Burke's observed the old woman lying as if dead, some of the straw being above her."

The witness mentioned there - a woman named Ann Gray - went with her husband to the police, who found blood on the straw at Burke's house. When they questioned Burke and his common law wife Helen McDougal about the old woman, each gave a contradictory account, so they were arrested. William and Mary Hare followed them to jail next day.

As I said earlier, Hare turned King's Evidence at this point, agreeing to testify against Burke and McDougal in return for Mary and himself being given immunity. Burke's trial came on Christmas Eve, 1828, and this is one of the ballad sheets it produced:

This sheet offers some highlights from the trial's transcript - again, probably lifted from one of the newspapers - which tell us how astonishingly unconcerned one of Burke's neighbours was to hear terrible violence in the next room. His name was Hugh Alston:

"He went to the flat where Burke resided and heard two men wrangling and struggling, and a woman crying murder, but did not consider her in imminent danger. That continued for about a minute, and then he heard a cry as if a person had been strangled."

That woman, of course, was Mary Docherty - Burke & Hare's final victim. Alston went out into the street to try and find a policeman, but gave up that quest almost immediately. When he got back into the lodging house, all was quiet in Burke's room again, so Alston decided everything must be fine and went to bed.

Docherty's murder gave the prosecution its best chance of convicting Burke, so that was the one it set out to prove. He was found guilty of that killing on Christmas Day and sentenced to hang.

The case against Helen McDougal was found Not Proven, but she - like the two Hares - was kept in jail after the trial anyway. This was done mostly for the trio's own safety, as many Edinburgh residents took a dim view of these three escaping punishment. If set free immediately, they may well have been lynched in the street.

So: we've got both Burke and Hare in prison, and Burke condemned to die very soon. That gave the ballad printers a chance to produce one of their favourite sheets of all - the Last Goodnight.

These sheets always took the same form. They presented a set of remorseful verses, supposedly written by the killer himself as he contemplated death in his cell. So miraculous was the power of the Last Goodnight that even men unable to write their own names somehow managed to compose the required verses!

In fact, of course, these Last Goodnights were simply knocked out by the same printers and hacks who produced the rest of the ballad sheets' copy. That fact's neatly acknowledged in the introduction to the sheet shown here, which says its verses are ones the writer "heard or imagined he heard" drifting out from Burke's cell at Calton Jail. Their content is pretty typical of the Last Goodnight's particular form:

"These shocking murders harass my soul,

Which cruelly I've committed,

For paltry gain, which ne'er lasts long,

For those who basely get it.

"My sentence therefore must be just,

For God's commandment says,

He that sheddeth another's blood,

His blood must it appease."

That ballad takes in the whole of Burke & Hare's career. Others focus more closely on just their juiciest killings. And the juiciest of them all was Daft Jamie's.

James Wilson, to give him his proper name, was a simple-minded lad of 18, who earned a few coppers by wandering barefoot around Edinburgh's Grassmarket and doing small errands for the traders there. He'd had a falling-out with his mother, which left him sleeping rough in whatever alleyway or stairwell he could find for the night.

Although he was physically imposing, mentally Jamie was merely an innocent child. He was a popular figure among the people of Edinburgh, who got used to seeing him playing with little children in the Grassmarket or stopping to share a pinch of snuff with one of his many friends there. Although everyone called him Daft Jamie, they did so with more affection than anything else.

Some versions of the Burke & Hare story maintain that it was Mary Hare who selected Jamie as a potential victim when she found him searching for his mother in the Grassmarket - and then led him back to Tanner's Close with promises to help him find her. That makes sense, as Burke & Hare themselves preferred to avoid any victim they might find it difficult to overpower. Their own chosen prey were women, children and the elderly, not strong young men like James Wilson.

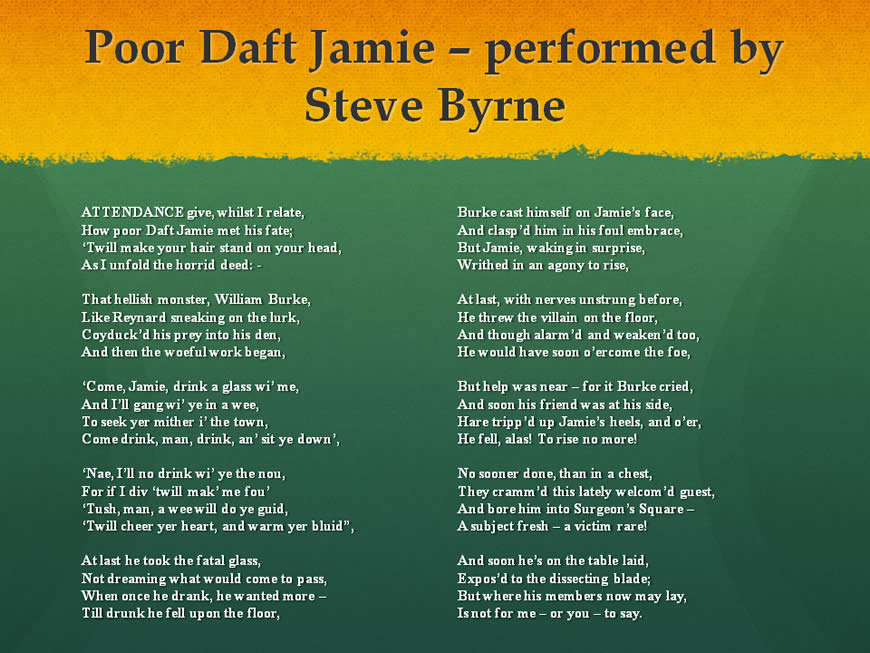

The ballad printers had much the same news values as our red-top tabloids have today, and Jamie's role as a "Holy Fool" among Burke & Hare's victims made him perfect fodder for their sheets. This one's my favourite example:

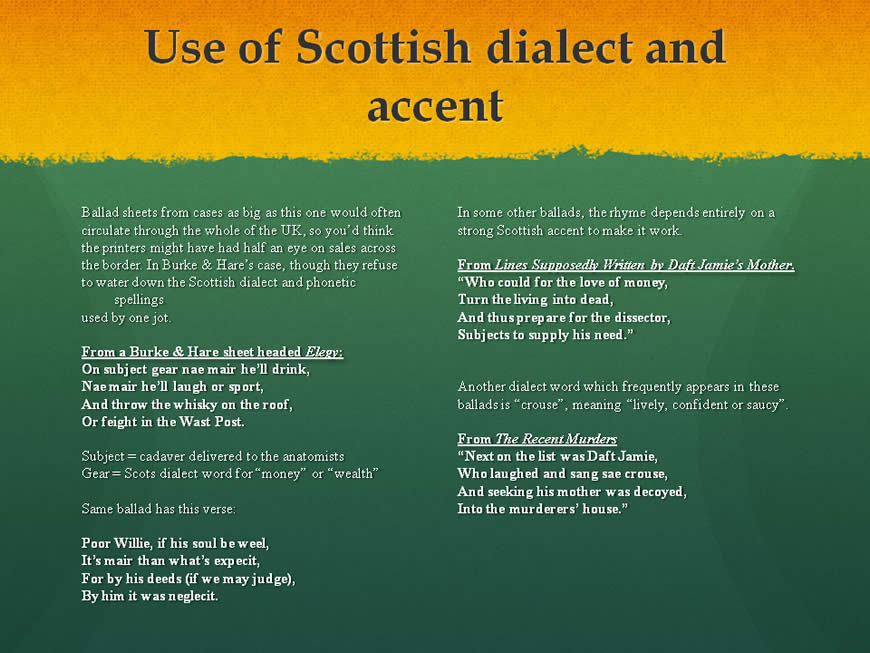

It's often assumed that all the verses you find on these sheets are sub-literate rubbish - and there's no denying that some of them are very bad indeed. In this case, though, the writer's crafted his verses quite carefully. In this section, for example, he uses phonetic spelling to contrast Burke's Scottish accent with the narrator's standard English:

"Come, Jamie, drink a glass wi' me,

And I'll gang wi' ye in a wee,

To seek yer mither i' the town,

Come drink, man, drink, and sit ye down.'

"At last he took the fatal glass,

Not dreaming what would come to pass,

When once he drank, he wanted more,

Till drunk he fell upon the floor."

And the other thing I love about this ballad sheet is that picture of the barrel. Here it is in close-up, together with the ballad printers' standard portrait of Jamie himself.

As you can see, the label on the barrel there reads "Alas! Jamie's pickled!" By choosing this picture, the sheet's printer seems to be saying that - as appalling as Jamie's murder was - it's kind of OK to laugh about it too. Anyone who's heard a sick joke told in the immediate aftermath of a modern killing will recognise the sentiment.

It's rare to find a touch of humour like this on a Burke & Hare ballad sheet, most of which are either mawkish or downright sadistic in tone. The barrel's also a nod towards two of the pair's other victims, a poor Irish woman and her young son. Another ballad sheet has these details about their demise:

"The female was bereaved of life while lying asleep on the straw. She was stripped and put into a herring barrel among brine. Hare strangled the lad over his knees by the fireside and thrust the corpse into the cask above his mother."

It's no coincidence that Poor Daft Jamie was produced by William Smith, a printer based in Edinburgh's Bristo Port neighbourhood. He was one of the most mischievous ballad printers in the whole city, and we'll see another example of his work in a moment.

As far as I'm aware, none of Burke & Hare's other victims had a ballad sheet devoted just to them, but Jamie's tale made such irresistible copy that he got several. Here's another example:

Again, I like the slightly tongue-in-cheek note here: "Lines supposed to have been written by Mrs Wilson". No-one's saying these lines were actually written by Daft Jamie's mother - merely that it seems a good a guess as any.

Once again, the verses stress Jamie's innocent character, in this case using both his friendship with the local children and his generosity:

"You was simple, inoffensive,

Loved by all where'er you went,

And their little bonnties cheered you,

And their smiles made you content,

"When you met your neighbour cronies,

Take or give a snuff would ye,

With your box and spoon sae happy,

To prime their noses aye so free."

That's a fair example of the mawkish Burke & Hare sheets I mentioned earlier. But here's another example of a ballad sheet where someone's taken gone that extra mile to get things just right:

What I have in mind here are the careful internal rhymes in the first, second and fourth lines of these verses:

"Let old and young, unto my song, a while attention pay,

The news I'll tell will please you well, the monster Burke's away,

At the head of Libberton Wynd he finished his career,

There's few I'm sure, rich or poor, for him would shed a tear,

"The injur'd crowd, they groaned aloud, this monster to behold,

Who in his time had thought no crime to murder young and old,

When the scaffold he did ascend, the people all did cry,

'Bring out Will Hare, we think it fair, that he should also die'."

A complex construction like that doesn't happen just by accident, and I do think the better ballad sheet writers deserve a little credit for their work. As it is, they don't even get a by-line on the ballad sheets themselves. The most we're given is a set of initials - "JP" in the case of Poor Daft Jamie - or an alias like "Wag Phil" which appears on the Robert Knox sheet we'll see in a moment.

But back to our story .

William Hare, Mary Hare and Helen McDougal were all released from jail soon after Burke's execution. The authorities dumped William Hare near the English border and told him never to set foot in Scotland again, but the two women were simply let loose on the streets of Edinburgh and left to take their chances there. We don't know what happened to any of them after that, though the best guess seems to be that all three eventually escaped to Ireland and ended their days there.

The fact that these three villains simply disappeared from history left their stories without the satisfying ending people yearned to see. Spotting this opportunity, the ballad printers stepped in to provide the closure real life could not. This produced a whole batch of what I call Revenge sheets.

There's no reason to believe that any of the stories told in these Revenge Sheets is true. What they all have in common, though, is an urge to show people that justice was served in the end. The law may have failed to punish Burke's three accomplices, but these sheets offer the reassurance that fate stepped in to ensure they suffered mightily anyway - and that's what people wanted to read.

In this first example, we're told that both Helen McDougal and William Hare have been killed by angry mobs. McDougal gets top billing, as her death is said to have occurred more recently than Hare's.

On April 25, 1829 - or so we're told - she was working at Deanston cotton mills, about five miles north-west of Stirling, when ths happened:

"She was attacked by a great number of individuals, most of them females, who attacked her furiously, seized her by the hair of the head and strangled her. One of the women dispatched her by putting her foot on her breast, and crushed her severely."

There's no location given for Hare's supposed demise, though it is dated to April 10, 1829. A mob surrounds the house where he's discovered to be staying, breaks down the door and begins searching every room. And then:

"Some person on the outside observed Hare coming out of the top of the chimney. He was brought to the ground, and in a few minutes his body was so much mangled that he was taken by the police to a surgeon's shop and his wounds dressed. But he died in the course of four hours."

It's characteristic of these Revenge sheets that Hare must always be given a long and agonising death - four hours in this case. Sheets recounting Hare's supposed fate - each telling a completely different tale - continued to appear for over ten years after Burke's execution, showing just how long this tale continued to grip the public imagination.

The chances are that all the ballad sheets' accounts of Hare's death are nonsense, whipped up from sheer imagination by an enterprising printer. It may be that the persistent folklore about Hare being thrown into a pit of quicklime by vengeful labourers and ending his days as a blind London begger began life on a ballad sheet just like the one above.

There was almost as much public resentment against Robert Knox the anatomist as there was against Hare himself. The ballad printers were keen to exploit this feeling, but a little nervous about taking on a respected establishment figure like Knox in a frontal assault.

Most tried to cover their backs by reducing the doctor's surname to a cryptic "K---". Even with this device in place, though, they still found ways to let readers know exactly who they meant.

This sheet was braver than most, topping its threats to hang the anatomists with a very recognisable portrait of Knox himself. The giveway is the empty eye socket - his left - which led his students to nickname Knox "Old Cyclops". And the verses come up with a little trick of their own:

"Men women, children, old and young,

The sickly and the hale,

Were murder'd, pack'd up and sent off,

To K---'s human sale."

The crucial word there demands two syllables to make the scansion work, and "Knox's" is one of the very few "K" names of that length to fit the bill.

"Were murder'd, pack'd up and sent off,

To Knox's human sale."

Another ballad sheet - this one titled The Recent Murders - nails Knox with its rhyme scheme alone. Its key verse describes Burke & Hare getting ready to transport their latest victims to Surgeons' Square:

"Which having done, they wrapped them up,

Then laid them in a box,

And without either dread or fear,

Sold them to Dr K---."

Let's see: an Edinburgh doctor, whose name has four letters, beginning with a "K" and we know it rhymes with "box". Who on Earth could they have in mind?

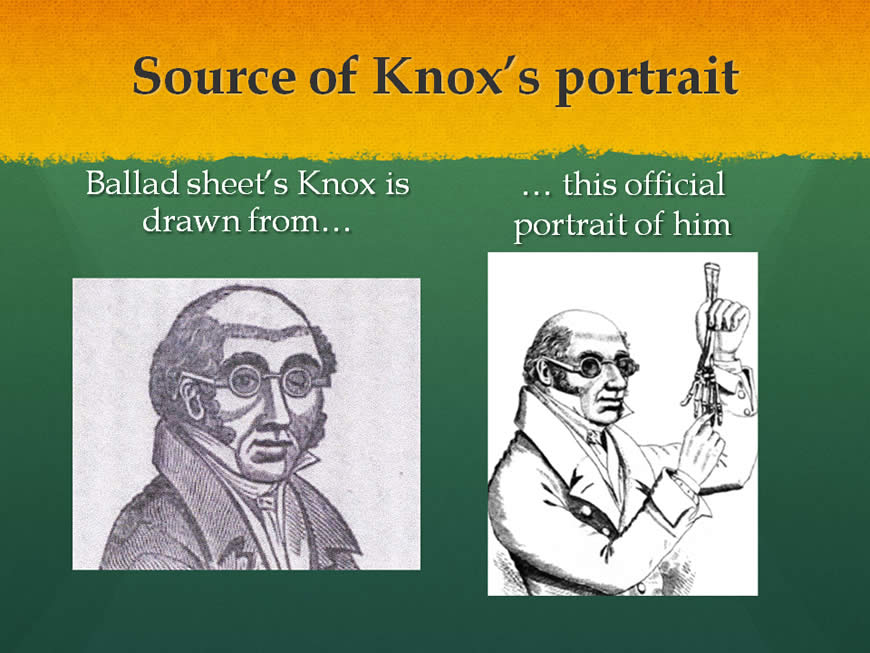

And should you still be in any doubt about that portrait of Knox being recognisable to the ballad sheet's buyers, then just take a look at its source:

You can see from this slide that the ballad sheet's artist simply produced his own version of an official pen-and-ink portrait of Knox. You can see the empty eye socket quite clearly in both these pictures - Knox lost the eye in a childhood attack of smallpox - and even the clothes he's wearing are identical.

Now let's have a look at one of the sheets actually sold at Burke's execution.

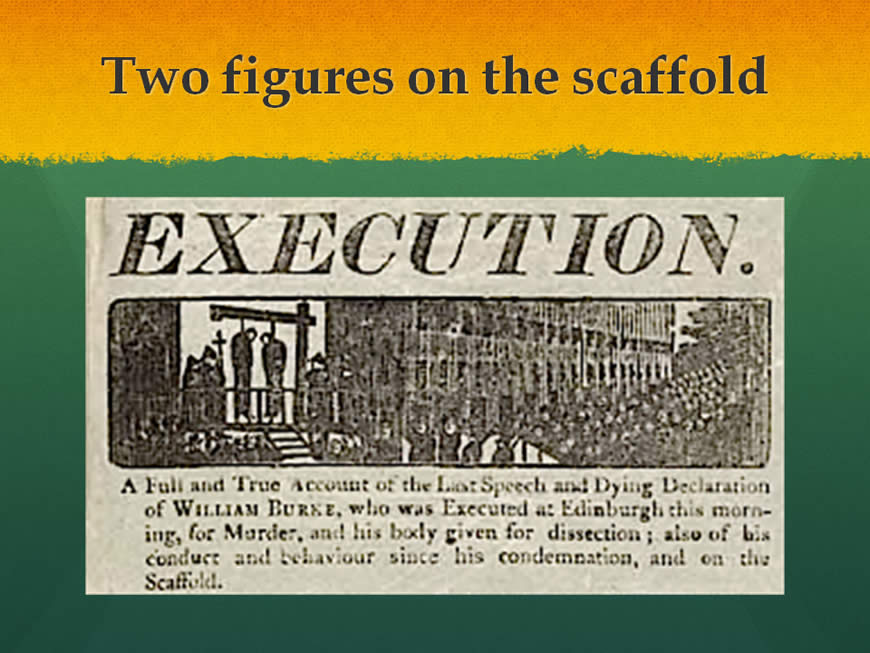

The sheet headed by this illustration amakes quite a big promise. And it's this:

"A Full and True Account of the Last Speech and Dying Declaration of WILLIAM BURKE, who was Executed at Edinburgh this morning."

But, in fact, it delivers no such thing. There's nothing there that's specific to Burke's hanging at all, simply a recitation of the various stages every hanging went through, dressed up to look like an eye-witness report of the day itself.

Tricks like this were often pulled to ensure printers could turn out their sheets on the night before the hanging and have them there in the crowd on sale before everyone dispersed. I've seen examples from one London printer who ran exactly the same stock description on two execution sheets sold at two different hangings on the same day. All he changed was the name of the condemned man.

But this sheet's also interesting for the illustration itself. Ballad printers were often very casual about which picture they matched to a particular sheet's story. Even so, I think there's more than simple carelessness at work here.

Burke hanged alone, but many of the people watching would have dearly loved to see Hare hanged beside him. So I wonder if it's just a coincidence that the printer here has chosen a picture which so clearly shows two figures dangling from the scaffold? If you wanted to sell your sheets, you had to give the people want they wanted, and even at this almost subliminal level, the two-shot he's selected there may have helped to shift a few extra copies.

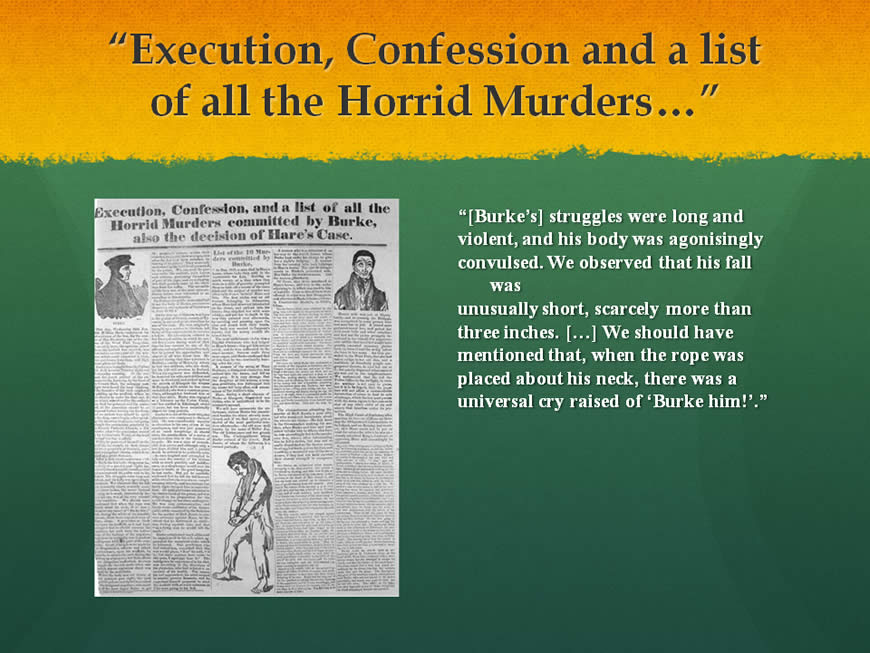

This next execution sheet - a much larger one that most we've looked at - offers a wrap-up on the whole case shortly after Burke's death. It's the equivalent of a Sunday newspaper today summing up a news story that's been developing all week into a single tidy package.

The details of Burke's execution given here are accurate enough to show they're a real eye-witness account, which means this sheet must have gone on sale a day or two after the hanging itself. It would have been sold around the streets of Edinburgh, hawked at any corner with enough footfall to drum up some trade.

The most striking thing about its account is the suggestion that the hangman deliberately gave Burke short rope in response to the crowd's sadistic cries. A short rope would deny him the mercy of a quick death from a broken neck, leaving him to slowly choke when the trap was pulled and the rope tightened.

Here's what the ballad sheet says:

"Burke's struggles were long and violent, and his body was agonisingly convulsed. We observed that his fall was unusually short, scarcely more than three inches. We should have mentioned that, when the rope was placed about his neck, there was a universal cry raised of 'Burke him!'."

Because Burke & Hare had stifled all their victims, "Burke" had instantly become a slang verb meaning "to stifle, strangle or choke", so there's no doubt what the crowd was demanding here. The only surprise is that the hangman seemed so ready - perhaps even so eager - to comply.

But let's see if we can and on a slightly happier note.

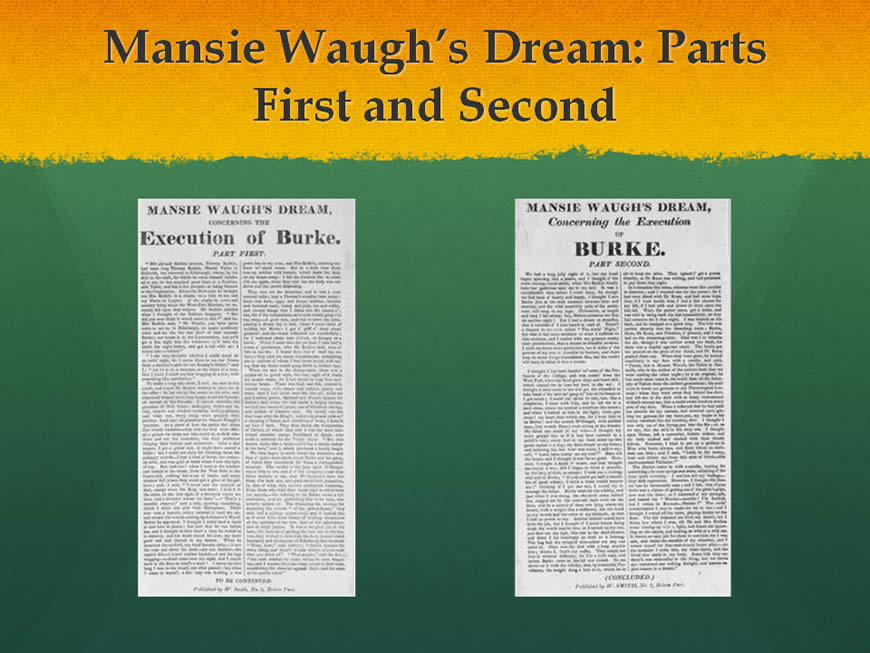

I promised earlier that we'd come back to the mischievous William Smith - he being the printer, you'll remember who gave us that picture of the barrel with Jamie pickled inside it. Smith never missed the opportunity to have a bit of fun with his own ballad sheets, and I think this next one might just be his masterpiece.

The full headline there, in case you can't read it, is

"Mansie Waugh's Dream concerning the Execution of Burke. Part First."

And then, over to the right

"Part Second."

So, who was this Mansie Waugh? Answering that question required a bit of detective work, but I think I have pieced the full story together now.

Mansie, it turns out, is a fictional character, created by David Macbeth Moir for his comic novel The Life of Mansie Waugh, Tailor in Dalkeith. The book was published in 1828, the year Burke & Hare were caught, and it proved a huge hit, so it was still very fresh in people's minds when Burke was hanged.

Mansie's a sort of Pooterish figure, made ridiculous by the contrast between his high pretensions and his small-minded rural ways. Moir wrote the whole thing in the first person, as if it were his character's own genuine autobiography.

As Burke's execution drew near, the Edinburgh Evening Post commissioned Moir to produce a short sequel giving Mansie's eye-witness account of the hanging and his thoughts on the whole event. The paper printed this account, and that gave Smith what he thought could be a very lucrative idea. Why not steal the Post's copy and recycle it in ballad sheet form?

And that's exactly what he did, producing the twin sheets you see above. He put Mansie's name prominently in their headlines to ensure they sold, but gives no mention at all to either Moir or the Post. Ballad printers routinely pinched news copy from the papers in this way, but this is the only case I've found of someone giving a literary creation the same rough treatment. It's also the only ballad sheet I've ever seen made to be sold in two separate installments. If you wanted the full story, you had to buy both.

This sort of stunt was entirely in character for William Smith. The National Library of Scotland's Scottish Book Trade Index has this entry for his Edinburgh business:

"He was in the habit of producing facetious chapbooks and [ballad sheets], and in 1832, he opened a shop to sell them at 111 Nicolson Street. He quarreled with his new neighbours and gave up his shop in disgust in 1834, having chronicled the quarrel at length in a curious periodical called The Advocate."

If Smith were alive today, I've no doubt he'd be quarrelling with the his neighbours all over again - and now he'd be describing every twist and turn of that quarrel in an angry blog.

The Book Index's reference to Smith's fondness for facetious ballad sheets helps to explain his use of Jamie's pickle barrel. He also published a very popular chapbook about Jamie's murder, details from which are still faithfully reproduced in sombre Burke & Hare studies today. Some of those details, I'm sure, are perfectly true. But I wouldn't mind betting that others simply sprang from Smith's fertile imagination.

And it's William Smith's work on Daft Jamie which brings me to the final little offering I have for you.

When I was preparing this talk, I sent these original 1829 lyrics from William Smith's Poor Daft Jamie - written by the mysterious JP, of course - to Steve Byrne of the great Scottish folk band Malinky. Steve agreed to put those 200-year-old lyrics to some of his own music for us, and turn them back into a living song. I'm delighted to say he's here to perform it for us tonight, so please join now me in welcoming . STEVE BYRNE!!

To hear Steve's performance of Poor Daft Jamie, recorded live as a conclusion to my talk, please click the SoundCloud link here. For more of Steve's music, visit www.stevebyrne.co.uk.

All the ballad sheets discused here can be found on the National Library of Scotland's Word on the Street website, where you can see the sheets for yourself and read their full transcriptions. It's well worth investigating.

I delivered this talk as part of the Edinburgh Festival's Burke & Hare day at One Royal Circus on August 10, 2014. To see some exclusive bonus slides for PlanetSlade readers, just continue scrolling down.