"[Lizzie] came up and placed herself on my lap as usual and, after fondling her for some time, I made a solicitation. To my infinite astonishment, she melted down like wax. [.] You would have done as I did, but what was my horror and heartsickness when I found the signs of her virginity wanting."

"[Lizzie] came up and placed herself on my lap as usual and, after fondling her for some time, I made a solicitation. To my infinite astonishment, she melted down like wax. [.] You would have done as I did, but what was my horror and heartsickness when I found the signs of her virginity wanting."

- Nicholas Dukes, writing to Lizzie Nutt's father on December 4, 1882.

"At 9:30pm, the indignation over the verdict is terrific and an excited crowd has just started toward the court house, where Dukes is in the charge of the sheriff. They carry a stuffed effigy of Dukes and of the twelve jurors. Violence is expected. At 9:45pm, the crowd reached the McClelland house a few doors from Dukes' room. They have suspended his effigy across the street and are singing, 'We will hang Dukes' body on a sour apple tree'."

- The York Daily, March 15, 1883.

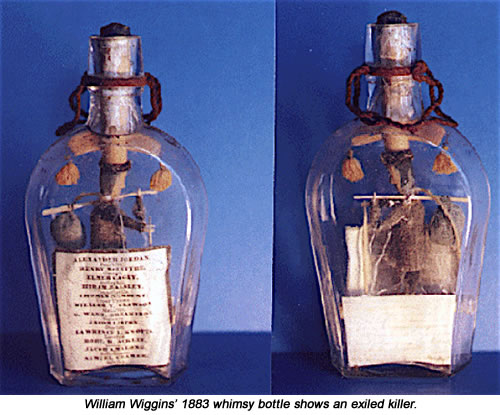

Not all murder ballads come in the form of a song: this one's constructed from glass, fabric and paper.

It's a bottle, just over six inches tall and sealed with a sturdy cork. There's an ornately knotted length of crimson string tied round the neck, draping down in a decorative loop over its front side. The glass is clear, the bottle flattened on its front and back with bulbous shoulders swelling out from a narrow base. Inside, there's a forlorn-looking figure, walking along the road with his head cast down and a hobo's stick-and-kerchief luggage over his left shoulder. Flanking him are the two scraps of paper which give us our only clues to this wanderer's identity.

The smaller of these two scraps is written out by hand and signed by the bottle's creator - a man named William Wiggins of Tipton in Pennsylvania. He dates his work too, telling us it was completed on March 30, 1883. "A foul seducer and murderer has been turned loose on the community of Uniontown, Pennsylvania," the note reads. "He has with him his lawyer and perjured jurymen, but the mark of Cain is on him: 'A fugitive and vagabond shalt thou be in the earth'." The closing quote there's from Chapter 4, Verse 12 of Genesis, giving God's final words to Cain as he exiles him for the murder of his brother.

Turn the bottle round and there's a list of Wiggins' 12 "perjured jurymen", clipped from an 1883 newspaper. They're all men and each has his role in the community noted below his name: the miner Henry McIntyre, the farmer Elmer Cagey, the blacksmith Robert Acklin and so on. Oddly, though Wiggins lists all the jurors' in such exhaustive detail, he makes no mention of the killer or victim's names. Uniontown's only 90 miles away from Wiggins' Tipton home, so for him this was a very local affair. Completing his bottle just two weeks after the verdict it describes, he clearly assumed everyone would already know who the killer was and just what the case involved.

Objects like these are known as Whimsy Bottles, Puzzle Bottles or Patience Bottles. Like the ships in bottles we all know, they demand delicate, intricate construction be carried out inside the bottle itself and hence give the makers a showcase for their craft skills and expertise. I first got interested in them after seeing a few examples at the Tate Gallery's 2014 British Folk Art Exhibition, which labelled its own display "God in a Bottle". There were five bottles on show at the Tate altogether, three of which were built round a central crucifix filling most of the space inside.

"The range of objects depicted within these bottles is varied, though certain themes are recurrent," the Tate's catalogue explains. "Many of them are religious in nature (hence their name) and among these, most contain crucifix scenes. Crosses are generally augmented by a number of symbolic carvings. A rooster, a ladder, a long stick with a sponge on the end, hammer and nails, pincers, a skull, a shovel, a lantern and a Bible are among the items frequently included." (1)

That immediately rang a bell with me, because I'd bought a very similar Mexican cross while visiting Houston back in 1992. Like the bottles the Tate described, my clay cross gives a sculptural account of Christ's crucifixion: The hammer used to drive nails into his hands and feet, the rooster which crowed to mark Peter's third denial, the vinegar-soaked sponge Roman soldiers used to mock Christ's thirst and so on. For these objects' makers - whether in Mexico or Pennsylvania - they added up to a vibrant narrative and a potent reminder of faith.

Back at home, I set about researching whimsy bottles online. They'd also been popular in the North of England, I discovered and one use for them had been to mark the death of a relative or close friend. The mourning relatives would construct a single straight-backed chair inside the bottle to represent the empty place at the family dining table their loved one had left behind.

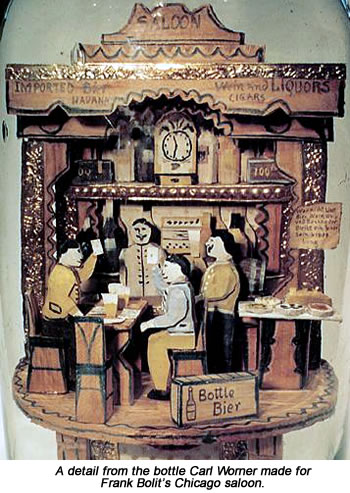

Another strand of the bottles' history led me to Carl Worner, a hobo who roamed Missouri and Illinois between 1900 and 1920. Worner would stop at saloons in every town, call for an empty bottle and few scraps of wood or fabric, then construct a painstaking bottle sculpture of the saloon's interior which he'd trade with the landlord for a hot meal and few free drinks. Most interesting of all, though, was the William Wiggins murder bottle I've already described.

I stumbled across that one on a 1999 website created by Arthur Wiggins, one of William's descendents. "As a child, I was always fascinated by those times when my father removed the bottle from my grandfather's desk and let me hold it," Arthur writes. "Then back away it went. Now that I am fully grown (71), I have an even deeper appreciation of the bottle. That fascination is enhanced by the fact that I discovered among my father's things an original 1883 copy of The Uniontown Republican Standard telling [.] of the happenings which led to the creation of the bottle." (2)

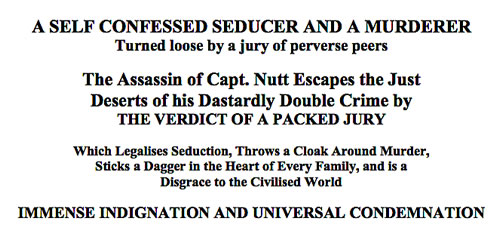

Thankfully Arthur also included a full transcript of the paper's story on his site, which was more than enough to get me started on my own research. Filling both the paper's front and back pages in its March 15, 1883 edition, this tells how a young lawyer named Nicholas Dukes slept with a Uniontown girl called Lizzie Nutt, wrote a letter to Lizzie's father informing him of this fact and then shot Captain Nutt dead when he demanded that Dukes marry the girl. The jury's verdict that Dukes should walk free on grounds of self-defence, the URS announced, was one which "legalises seduction, throws a cloak around murder, sticks a dagger in the heart of every family and is a disgrace to the civilised world". Uniontown's citizens rallied round this call, threatening to lynch both Dukes and the jury that freed him.

It's a great story, but one which wasn't even close to concluding when that issue of the URS came out. By the time its ramifications had fully played out 12 years later, three more people had been shot and Nutt's son was in prison.

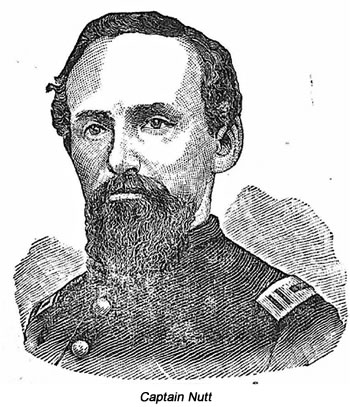

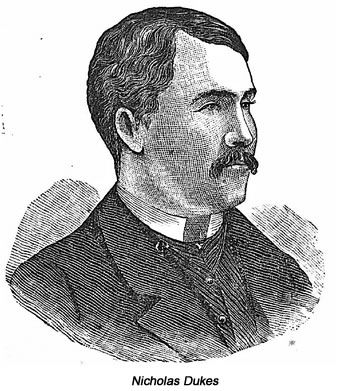

Nicholas Lyman Dukes was in his early thirties when he first met the Pennsylvania beauty Lizzie Nutt at her family's Uniontown home. Lizzie, then just 22, was the daughter of Captain Adam Nutt, a former Civil War soldier who'd fought for the Unionist side at both Fort Wagner and Morris Island. Now a banker, Nutt was known and respected throughout the county as a man who placed great importance on both his own and his family's honour. His work with Pennsylvania's Treasury Department in Harrisburg meant he was often away from home, however, leaving him little time to police his daughter's social life.

Nicholas Lyman Dukes was in his early thirties when he first met the Pennsylvania beauty Lizzie Nutt at her family's Uniontown home. Lizzie, then just 22, was the daughter of Captain Adam Nutt, a former Civil War soldier who'd fought for the Unionist side at both Fort Wagner and Morris Island. Now a banker, Nutt was known and respected throughout the county as a man who placed great importance on both his own and his family's honour. His work with Pennsylvania's Treasury Department in Harrisburg meant he was often away from home, however, leaving him little time to police his daughter's social life.

Dukes at this time was a lawyer and aspiring politician. He'd graduated from Princeton in 1873, been called to the Fayette County bar three years later and now had a growing legal practice of his own. Although defeated in his 1878 bid to win the Democrats' nomination as Fayette's District Attorney, he was subsequently elected as the county's representative in Pennsylvania's legislature.

Evidently, he caught Lizzie's eye, because at some point in 1881 or 1882, she invited him to join her and a couple of friends for an evening's socialising at the Nutt family home. When he arrived, he found just two other guests present: a young man called AC Hagan and a Miss Breckenridge, who was related to one of Captain Nutt's colleagues at the bank. By the standards expected of a respectable young woman at the time - when chaperones were thought obligatory - this was dangerously racy stuff. (3)

Dukes visited Lizzie several times in the coming months, often seeing her alone and by June 1882 he was writing letters to her protesting his love. His passion can be gauged by the fact that he signs off one of these letters with the phrase "Gaspingly yours". Things soon went off the rails, though, leading Dukes to compose an anonymous letter to Nutt which he was seen dropping near the family's house in October 1882 and which Lizzie later confirmed her father did receive. We don't know exactly what that anonymous letter said, but it's a safe bet that it raised many of the same doubts about Lizzie's character which Dukes would set out in his notorious signed letter a few months later.

We know from Dukes' background that he was an intelligent and educated young man - which makes his signed letter to Nutt all the more inexplicable. Dukes himself later admitted this letter had been "a most appalling blunder" on his part, calling his decision to write it "the personification of stupidity". Whenever he looked back on the letter, he said, "I can scarcely resist the conclusion that I was labouring under temporary insanity". It's tough to argue with that, and the letter itself is worth considering in some detail. (4)

Dukes wrote the letter on a sheet of his law practice's business stationery, dating it December 4, 1882 and adding a note that it should be read in private. "What I have to communicate concerns your daughter and will almost drive you to madness, because I know how you worship her," he tells Captain Nutt. "Let come what may, the blow must fall and the sooner I take it, the better in order that the calamity may in some degree be averted." (5)

He goes on to describe his first meeting with Lizzie and the social evening I mentioned above. "Lizzie said to Mr Hagan that she had something to tell him," Dukes writes. "She told him to come into the next room and she would tell him. They shoved the sliding door back just far enough to pass through and went into that room and remained there in total darkness about half an hour. I was astonished, but thought her youth and inexperience palliating circumstances and excused her."

A few weeks later, Dukes says, Lizzie invited him over to the house again, this time for a solo visit. He says she came to sit "very near" him and confided that she'd burnt her hand.

"I took hold of her hand in order to turn it into a position to see," he writes. "She made no attempt to withdraw her hand, but let it rest in mine. I placed the other hand lightly upon it also and, just for fun, I made a feint as if to kiss her. I was utterly surprised when, instead of withdrawing her face from me, she absolutely advanced her face to meet me. Of course, such a reception flattered my vanity and I began to feel an interest in her. I went away and promised to call again soon."

Two weeks later, he was back at the house again, this time seemingly unannounced. "As I was passing in front of the large window of the front porch (the shutters nor blinds were not up yet) I saw opposite the window upon a sofa Hagan with his arms about her," Dukes claims. "I stood a moment and watched him fondle her with no objections from her. My dream was dispelled and I turned my head and walked home."

If Dukes' account is to be believed, he then made an effort to stay away for a while, but was tempted back by Lizzie's notes asking why he never came to see her anymore. "I would then call and would be received in the utmost cordiality and treated with all appearance of preference," he writes. "I felt flattered by her attentions and things ran on in this way for a year or such a matter, I making occasional calls.

"All this time there came a swarm of young men calling there, each thinking he had the preference. Hagan thought he was first and told me frequently how he fondled her. He showed me notes from her inviting him out. Then Frank Hellen told me she was mashed on him and showed me several very cute notes from her. He told me how she kissed him the night of a party there and how she squeezed his hand every time he passed her in the grand chain.

"Things went on in the same way and one evening while calling there I just thought I would set a trap for her. Mr Kennedy was calling there quite frequently and I had an idea that he was one of the preferreds [.] I told her that I had come out one evening and heard voices in the parlour and as one of the shutters was just partially opened, I lifted myself up and looked in at the window and saw her and Kennedy on the sofa with his arms around her. She looked confused and said it was not true. I said it was no use to deny it because I saw it with my own eyes. She then said she never did it but once. I then told her it was not Kennedy I saw, but Frank Hellen. She says, 'Well, I don't care if you did'.

"The next time I called I determined to test her," Dukes continues. "She came up and placed herself on my lap as usual and, after fondling her for some time, I made a solicitation. To my infinite astonishment and grief she melted down like wax. Oh, how I pitied her weakness. But where is there a man that could resist the temptation of such beauty and loveliness? You would have done as I did, but what was my horror and heart-sickness when I found the signs of her virginity wanting.

"I afterwards reproached her with it and she denied it. I told her it was no use; that I could not be deceived and that I should think all the more of her if she would tell the truth. After considerable bandying, she broke down in a flood of tears and said it was Jess Bogardus and went on to explain how she met him frequently through a Miss Donaldson; that she was young and did not know any better."

Shortly after this encounter, Dukes reports, he was spying on Lizzie again - this time from a spot near the front door - when he saw her and a man called Nathaniel Frey kissing farewell after his (Frey's) latest visit. "This same brute of a Frey was in Reis' clothing store not long since and quite a number of other young men were present." Dukes writes. "Lizzie happened to pass with another young lady and he remarked that Liz Nutt had the nicest leg in this town. Someone asked him how he knew. He says 'By God, I have felt it from her heel to her hip'. I know two young men whom Frey told in confidence that he had all the favours he wanted from her on the floor of the parlour.

"This brings me to the point to which my foregoing remarks are preliminary and that is, unless precautions are duly used, she will become a mother. Just when I am unable to say. She don't really know her condition, but she fears it. You can save her from open disgrace and none but you can. [.] Captain, believe me when I say this is the hardest thing I ever did in my life. I know this letter seems like stabbing you in the back, but in my humble judgement it is the only means to save both her and you from shameful disgrace."

Dukes wrote this letter on December 4, then carried it around with him for a week before finally posting it on December 11. The careful evasions which Victorian etiquette demanded when discussing sexual matters blunt the force of it for us today, but receiving it must have hit Nutt like a sledgehammer. To put ourselves in his shoes, we have to imagine a modern father checking his e-mail over breakfast and discovering this:

I've been shagging your daughter Lizzie and now she's up the stick. Don't expect me to take responsibility for the brat, though, because, let's face it, it could be anybody's. Half the blokes in town have had Lizzie. If I were you, I'd get the little slapper an abortion.

Sincerely

Nicholas Dukes. (6)

For a Victorian man of honour like Nutt, this was intolerable. On December 17, he fired back a scorching reply. "You write to me as if you considered me a shameless coward and even suggest for me the hideous office of the abortionist," he says. "I shall convince you that I have the physical courage to espouse my daughter's cause and defend the honour of myself and my family and, further, that I have the moral courage to rest secure in the approval of the community in which I live should this whole miserable affair become fully know to the world." (5)

He dismisses Dukes' letter as "the plea of a quibbler", saying that - if Dukes had earlier discovered Lizzie was not a fit companion - then he should have stopped seeing her immediately. "You say that you have done as I would have done. In this you are a base liar. The daughter or wife of any friend or associate of mine would be safe under any circumstances in my charge. You have no right to suggest that I could possibly be a libertine or betray a weak, confiding girl. I have always held that when a man invades the sanctity of a home, he takes his life in his hands and under this code I shall act. It rests with you whether this affair ends in a legal farce or a tragedy.

"This commonwealth is not big enough for both of us, under existing complications. [.] On the 23rd at 8pm, you can see me quietly, peaceably at home. After that, if matters are not readjusted I shall precipitate a meeting. You can call this a threat or what you please." (7)

Nutt is saying here that, if Dukes fails to make Lizzie an honest woman by marrying her (that's the legal farce he mentions), then Nutt will damn well come round and shoot him dead (the tragedy). Nowhere in his letter does Nutt deny Dukes' charges that Lizzie has been promiscuous, nor his claim that she's now pregnant. Indeed, his proposals for a shotgun wedding suggest he accepts both these things are true. "I [have] showered on my poor daughter's head a volley of curses without giving her a chance to say a word," he adds. "For this I shall hold you personally responsible as well as for many days and nights of sleepless agony."

Nutt also accuses Dukes of avoiding him, saying Dukes had known fell well that he (Nutt) would be at home on December 14th, 15th and 16th of December and so had deliberately avoided calling at the house on any of those days.

On December 19, Dukes replied with a letter saying he would rather die than marry a woman of Lizzie's reputation. "You offer me the party spoken of or death," he writes. "I choose the latter alternative. I cannot accept for my wife the toy of the town and thus become the butt of the town's mocking derision. Death is far sweeter.

"I declare in all soberness that I doubt if I am the author of the present difficulty. If I were, I have committed no such heinous offence as you charge, because the girl is not what she ought to be. Had she been a chaste woman and I had seduced her, then your anathemas and proposed violence would have been perfectly justifiable. Had such, however, been the case, the present circumstances had not existed because she would have been my wife without controversy.

"It is not your daughter I refuse to marry. There is no reason why I would object to an alliance with a pure daughter of yours, but you insist that I shall marry a wanton woman simply because she is your daughter and has been unfortunate. The demand is unreasonable."

Dukes goes on to say he quite agrees with Nutt's assertion he should have quit Lizzie the minute he discovered she was no longer a virgin. He failed to do so, he claims, only because Lizzie became very frightened when she started missing her periods and he was merciful enough to try and comfort her. He then turns to the subject of Nutt's threats:

"You affect horror at becoming an actor in a peccadillo and, at the same time, appoint yourself a murderer and an assassin," Dukes writes. "Your letter would clear me if I should take your life on sight, but I don't want your blood. I shall not harm you in any instance. You may murder me if you will. I shall not arm myself, but don't lay to your conscience the flattering unction that the sentiment of the community will sustain you in your assassination. The woman is better known by the community than you know her and her name is scarcely ever mentioned without a sneer. Why don't you go shoot Frey and Bogardus and Kennedy and all the tribe?

"I understand why you want a meeting with me, but I must decline the one proposed. I don't care to walk into a death trap, but if you want to see me you can call upon me at my office at 8 o'clock, December 23, or at my room at the same hour, whichever you may indicate."

Once again, it might be useful to imagine the brutal content of Dukes' letter as a modern e-mail. In this case, his message to Lizzie's father was as follows:

I'd rather die that marry your slag of a daughter. Everyone knows she's the town bike and we've all been laughing about that behind your back for months. There's barely a bloke in town she hasn't shagged, so why do you assume I'm the one who knocked her up?

You're a thug and I'd be quite entitled to shoot you down in self-defence. Any meeting we have will be on my terms, not yours.

Sincerely

Nicholas Dukes.

Dukes posted this second letter on December 19 and then thought better of the assurance he'd given in its final paragraph. Next day, he called at Springer's Hardware Store to enquire about buying a pistol.

Captain Nutt was working at the treasury in Harrisburg on Saturday December 23 - the day Dukes had proposed for their meeting - but returned to Uniontown next day determined to confront the man at last. That evening, at what must have been around 8pm, he went to the McClelland Hotel, where he met with his nephew Clark Breckenridge. Breckenridge was a cashier at People's Bank in Uniontown, where Nutt worked when not busy with his treasury duties.

Captain Nutt was working at the treasury in Harrisburg on Saturday December 23 - the day Dukes had proposed for their meeting - but returned to Uniontown next day determined to confront the man at last. That evening, at what must have been around 8pm, he went to the McClelland Hotel, where he met with his nephew Clark Breckenridge. Breckenridge was a cashier at People's Bank in Uniontown, where Nutt worked when not busy with his treasury duties.

The two men walked over to the bank, where Nutt deposited $625 in hs family's account - a sum worth over $14,000 today. As they prepared to leave the bank again, he asked Breckenridge to wait a moment. "I have some trouble on hand," he said. "I have lately received two infamous letters from Nicholas Dukes, which I will show you. I want to see Dukes this morning and have an interview with him, as I return to Harrisburg tomorrow." Nutt was well aware that this interview could turn deadly, and seems to have made the bank payment to ensure his wife and children were provided for if only Dukes survived. (8)

Breckenridge later testified that he'd glimpsed a pistol grip in Nutt's pocket during this conversation, a point confirmed by the captain's wife Charlotte, who said he'd routinely carried that revolver with him ever since taking a job at the bank. Whatever misgivings he might have felt, Breckenridge agreed to accompany his boss to the Jennings Hotel across the street, where Dukes had lived for the past eight years. He explained their errand to James Feather, the hotel owner's son-in-law, who told its black porter Lewis Williams to take Breckenridge up to Dukes' room on the second floor. Nutt followed them up the stairs.

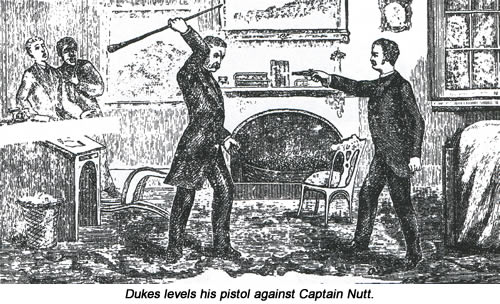

Williams knocked on Dukes' door, Dukes opened it in reply and Breckenridge explained that Captain Nutt wanted to speak with him. Dukes invited Nutt in, Nutt entered and Dukes closed the door behind him. Williams was heading downstairs again by this time, but Breckenridge stayed waiting outside the room. Feather came up to collect something from the room opposite Dukes' and stopped there to exchange a few words with Breckenridge in the corridor. A moment later, they heard the sound of a violent struggle inside Dukes' room.

"I heard someone cry 'Murder', but could not recognise the voice as it was somewhat smothered," Breckenridge later testified. "Immediately after that, I heard Captain Nutt call 'Clark! Clark!' and I opened the door. They had scuffled for almost a minute before I went in. I could not say who cried 'Murder' but I recognised Nutt's voice when he cried 'Clark!'.

"I found the two men clinched in a bending position, with Dukes' arm over Nutt. They were close by the bureau, between the foot of the bed and the wall. I jumped between them and separated them partly. Captain Nutt said, 'Take hold of him!' I got them separated and Nutt and I went to the mantelpiece. While standing with my back to the other parties, I heard a pistol shot. Nutt threw up his hands and fell."

Feather and Williams, who'd both burst into the room a moment after Breckenridge, backed his account. As Breckenridge was pushing Nutt back towards the mantelpiece, Feather was shoving Dukes to the room's opposite corner, trying to get as much distance between the two men as possible. "I saw Nutt and Dukes scuffling near the foot of the bed," Feather said. "After we got them separated, I said to Dukes 'What does this all mean?' He said, 'He came here to whip me!' I said 'Well, he can't do it now.' I think he repeated the remark and he was fumbling around in his clothes. He then pulled up his revolver and fired."

"I was the last one to go into the room," Williams added. "The two men were trying to throw each other down. Feather said to Dukes just before the shot, 'You've made a hell of an ass of yourself'." Dukes raised the gun in Nutt's direction again, but Feather managed to wrestle it away from him.

All three witnesses were adamant that, although Nutt had made efforts to reach the pistol in his overcoat pocket immediately after the shot, he'd still not managed to pull it out when he died. "Dukes and Nutt were nine or ten feet apart when the shot was fired," Breckenridge said. "Nutt, after they were separated, stood by the mantelpiece in an exhausted condition. He was not doing anything at the time he was shot.

"My best recollection is that his right arm was raised and resting on the mantel just at the [moment of the] shooting. He had no pistol in his hands when Dukes fired. He fell on his face a little to the left side, did not say anything when he fell. I saw that one of his eyes was out of the socket and he was bleeding freely. I held him in my arms and saw his hand and felt it going down toward his overcoat pocket. Nutt was left-handed."

"Nutt was resting with his right hand on the mantelpiece and his left hand hanging down," Williams confirmed. "I saw Nutt make two motions towards his pocket, after the shot, with his left hand." And here's Feather: "Nutt, at the time he was shot, was not doing anything. [.] Nutt had no revolver in his hand at the time."

After the shooting, Dukes left his pistol with James Feather, who also took charge of the gun Breckenridge had now removed from Nutt's pocket. "Duke's pistol had one shot fired out when I examined it and Nutt's none," Feather later recalled. Dukes had managed to get Nutt's cane away from him at some point in the fight too, but handed this over to Mr Jennings, the hotel's owner, when it became clear Nutt was no longer a threat.

He then calmly walked out if the room, announcing that he was heading over to Sheriff Hoover's office to surrender himself into custody. Descending the hotel stairs, he had a brief conversation with the owner's wife. "Oh Mr Dukes," she asked. "Why did you do this?" He replied: "I am very sorry, Mrs Jennings, but I had to do it or he would have killed me."

Mrs Jennings fetched a local doctor named JB Ewing to the room, who found Nutt still clinging to life on the bed where Breckenridge and Feather had laid him. He lasted for about 20 minutes after the shooting, during which time Ewing was able to establish that Dukes' pistol ball had entered just below his left eye and lodged deeply in the brain. Ewing and his colleague Dr Smith Fuller also noted a wound on the top of Nutt's head, marking the spot where Dukes had struck him a heavy blow during their fight. Dukes had not come out of the fight unmarked either, but had a vivid bruise on one arm where he'd tried to shield his own head from a blow by Nutt's cane. Sheriff Hoover dutifully recorded this wound in the station records as he escorted Dukes to a cell. By 11pm, Nutt was dead and Dukes safe in custody. Now the real fun could begin.

Reporters fell on the prospect of a Nutt/Dukes trial with glee. "This town has rarely been so excited," the Daily Alta California gasped. "Both men were of social prominence." (9)

Reporters fell on the prospect of a Nutt/Dukes trial with glee. "This town has rarely been so excited," the Daily Alta California gasped. "Both men were of social prominence." (9)

The same story then gives what amounts to a fight card profiling the two men, reminding readers of Dukes' law practice, his previous good character and his reputation for hard work. "He is sober, industrious and stands high at the bar and in the community," it sums up. Turning to Captain Nutt, it lays out his roles at the bank, the treasury and Pennsylvania's historical society. "He was attached to his family with a devotion that is rarely equalled," it says. "His eldest daughter [Lizzie], an accomplished young lady just blooming into womanhood, was the apple of her father's eye. Upon her, he lavished care and money without stint."

Details of the letters passing between Dukes and Nutt had evidently been leaked, allowing this same early report to tease the scandalous details which everyone knew must be fully revealed in court. No wonder the papers were drooling. On December 29, after the coroner's inquest, Dukes was committed for trial. At that point it looked like the worst charge he might face would be manslaughter, so he was freed on bail of $12,000 to await his day in court. On the same day he was released, he made out his will, evidently fearing that - no matter what reassurances his lawyers offered - his trial might yet lead to the gallows.

The prosecution team handling Dukes' case was headed by District Attorney Isaac Johnston, aided by two men called Playford and Boyd. Dukes hired the firm of Boyle and Mestrezat to handle his defence. Judge Alphonse Wilson would preside. Public sentiment against Dukes was already hardening in Uniontown, which may explain why the authorities decided to take a tough line and go for the most serious charge available: "wilful and malicious murder". Dukes responded with a plea of not guilty on grounds of self-defence. He did not deny he'd shot Nutt, but maintained he'd done so only because the need to defend his own life left no other choice.

Jury selection consumed most of the trial's first day on Saturday March 10, 1883. So contentious was this process that one side or the other rejected all but five of the first 57 candidates presented. Eventually a full jury was found, however, and the trial proper got under way on March 12.

Lawyers, family members and curious spectators flooded in to Uniontown's courthouse. "Captain Nutt's widow and her sister, Mrs B. Downs, walked in, clad in heavy mourning and amid profound silence, took their seats near Stephen R. Nutt [the captain's brother]," the Uniontown Republican Standard reports. "Mrs Nutt scarcely moved after sitting down, save for the convulsions that were visible as she listened to the story of the murder of her husband. Dukes' face lacked the composed expression of Saturday; it was flushed and betrayed uneasiness."

The first witness called was Clark Breckenridge, who described the events of the fatal day just as I've set them out above. James Feather, Lewis Williams, Mrs and Mrs Jennings and the two doctors all added their own testimony, which confirmed Breckenridge's account in every important respect. Everyone agreed that Captain Nutt had made no move for his own gun until after Dukes shot him - a point the prosecution was keen to emphasise as it challenged Dukes' claim he had acted purely in self-defence.

Hoping to establish a degree of premeditation in the killing, the prosecution also called William Pickard, a clerk at ZB Springer's Uniontown hardware store. Pickard testified that Dukes had bought the murder weapon there on December 21 - just three or four days after receiving Captain Nutt's threats against him. Dukes, it seems, was already anticipating the December 23 meeting he's proposed to Nutt and wanted to be prepared for it.

"He said he wanted a pistol that was good and sure," Pickard told the court. "I showed him a double-action and two or three others, one a Smith & Wesson single-action and the other the American. They were all three of .32 calibre, perhaps one of .38."

This distinction between a double-action and a single-action pistol is important. The hammer on a single-action pistol has to be cocked manually as a separate operation before the trigger is pulled, but a double action pistol does this automatically. One simple pull of the trigger with a double-action pistol and the bullet is speeding towards its target. Dukes, who seems to have had little experience with guns, wanted to be sure he wasn't left fumbling with a single-shot pistol's cocking hammer just when his life might depend on a speedy response.

Pickard found Dukes a different Smith & Wesson pistol to consider, this one a .32 calibre double-action model. "He then said he wanted a double-action: 'something that was sure'," Pickard reminded the court. "He also asked about the cartridges. I showed him a .32, a .38 and a .22 cartridge. He took the .22 and the .32 and went out, saying he would be back. He came back in ten or 15 minutes, looked at the revolver and purchased it.

"While examining it, he stood near the showcase in the front part of the store. A couple of customers came in and Dukes stepped around the end of the showcase, saying he didn't wish everyone to know his business there. He walked to the back part of the store, where he stood looking into another case until the customers went out. He then returned to the front of the store and purchased the .32 calibre Smith & Wesson, double action."

Judge Wilson had warned the prosecution team against quoting from Dukes' letters in their opening statement, and the defence did its best to prevent them being accepted in evidence at all. They knew Dukes' accusations against Lizzie - made to her father of all people - could only hurt their client's case. When the prosecution presented the letters a second time, though, Wilson over-ruled all the defence's objections and said they could be read aloud in full. Mrs Nutt, who'd already confirmed her husband had shown her both the letters, was led out of the courtroom to spare her the ordeal of hearing them again.

"During the reading, Dukes kept his gaze fixed steadily down to the floor," the URS reports. "Judge Wilson turned his face away, looked pale and seemed with difficulty to refrain from tears. Fathers bowed their heads in tears and grief as they listened to the horrible sentiments written to a father about a daughter whom he loved and fairly idolised."

Although the letters had no bearing on what had happened in Dukes' room on the day of the shooting, they did succeed in making everyone thoroughly dislike Dukes. This feeling began in the courtroom, where Johnston ensured their every unsavoury detail was driven home, but soon spread through the whole town and beyond. Captain Nutt's prediction that the community would take his side was more than borne out.

When the defence team's turn came, they began by calling attention to any small discrepancies in Breckenridge, Feather and Williams' testimony. On the crucial point of exactly when Captain Nutt had reached for his gun, they hoped to either drive a wedge between the three key witnesses' accounts, or to exploit any minor differences in wording between their trial testimony and what they'd told the coroner.

When this approach made little headway, they began trying to smear the witnesses' character, saying Breckenridge's testimony could not be trusted because he was a relative of Captain Nutt's, and suggesting Feather held some unspecified grudge against Dukes. They could produce no evidence of this supposed grudge, and Feather countered their charge by pointing out he'd actually voted for Dukes in the recent election for Fayette County's legislature.

The defence stressed also that Nutt had been armed with a sturdy cane when he entered Dukes' room and reminded the jury of what a heavy blow that cane had inflicted on their client's arm. Sheriff Hoover was called, and testified that the bruise that blow left behind could still be plainly seen five days after Dukes gave himself up.

"Nutt went into Dukes' room armed, on a Sunday morning, speaking to nobody as he walked in," the defence team's Mr RH Lindsey told the jury in his summing up. "As soon as he entered, a scuffle ensued. Who, in all reason, was the aggressor in this struggle? Evidently the invading party."

Finally, Lindsey had no choice but to address the thorny issue of Dukes' letters. He cautioned the jury against allowing themselves to be influenced by public prejudice against his client and then added: "I do not claim anything for Dukes because he has been honoured by his county with a seat in the legislature any more than if he were the lowliest citizen. I remind you that Mr Dukes' letters have nothing to do with the making up of your verdict."

Judge Wilson told the jury that they must decide whether Dukes was guilty of any crime and, if so, whether that crime was first degree murder, second degree murder or voluntary manslaughter. "There must be malice and a fully-framed purpose to kill in order for the offence to be murder," he reminded them. The jury retired to consider its verdict at 4:30pm on March 14 and returned at about 8:00 o'clock that evening.

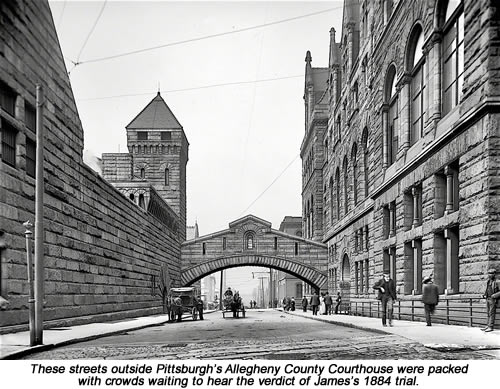

Public opinion was nearly unanimous that the verdict would be one of murder. With Dukes' fate now about to be announced, the public gallery was full to bursting with a noisy and excited crowd of spectators. "When silence was partially restored, the jury filed in and the frivolous expression on some of their faces betokened the nature of their verdict," New Castle's Daily City News reports. "To the question of the clerk, Foreman McIntyre answered 'Not guilty'." A shocked silence in the gallery gave way to angry protests, which the DCN says "were with difficulty restrained by the officers". (10)

"Dukes sat down with great composure," its report continues. "Judge Wilson looked amazed at the announcement and said, 'Gentlemen of the jury, I suppose the verdict that you have rendered is one that you thought you should render under your oaths, but it is one which gives dissatisfaction to the court, because we thought the evidence was sufficient to justify you in rendering a different verdict. If you have committed an error, it is one that we cannot avoid, but can only express our condemnation of it in this mild way. The prisoner is discharged."

The court's decision to free Dukes did not go down well. The spectators packing the public gallery sat in dumbfounded silence for a moment, then began hissing their disapproval. An angry mob followed the jurors from the courtroom into the snowstorm that was now raging outside, flinging curses at them all the way, and the jurors fled anxiously to whichever address each man thought would keep him safest. "They were compelled to seek cover among the jeers and howls of the excited populace," the New York Times reports. (11)

The court's decision to free Dukes did not go down well. The spectators packing the public gallery sat in dumbfounded silence for a moment, then began hissing their disapproval. An angry mob followed the jurors from the courtroom into the snowstorm that was now raging outside, flinging curses at them all the way, and the jurors fled anxiously to whichever address each man thought would keep him safest. "They were compelled to seek cover among the jeers and howls of the excited populace," the New York Times reports. (11)

"The jury seemed to be aware of the odium which they had heaped upon themselves and the county, for they skulked out and disappeared," adds the URS. "Two of them got up in the vicinity of the McClelland house, where they found the crowd burning Dukes' effigy and singing, 'We'll hang Lyman Dukes from a sour apple tree / Dukes will go down to Hades and the jury will meet him on the way'. This frightened the two jurors and they disappeared."

The York Daily's reporter gives a minute by-minute account of the evening's events. "At 9:30pm, the indignation over the verdict is terrific," he writes. "An excited crowd has just started toward the court house, where Dukes is in charge of the sheriff. They carry a stuffed effigy of Dukes and of the 12 jurors. Violence is expected. At 9:45pm, the crowd reached the McClelland house a few doors from Dukes' room. They have suspended his effigy across the street and are singing, 'We will hang Dukes' body on a sour apple tree'." (12)

Some jurors didn't even make it home that night. Two stayed at Hall's boarding house in Peter Street, where the URS tells us they took the precaution of sleeping fully clothed in case they had to flee again in the night. "In the morning, they tried to get someone to go up to the courthouse to draw their pay," the paper says. "No set of men were ever so anxious to get out of a town which they had so disgraced. After drawing their pay on Thursday morning, they hastened to depart, being hooted at and some of them leaving by the back streets. They did not relish seeing the effigies of themselves and Duke adorning various telegraph poles."

The next day, in Shoemakersville, 200 miles east of Uniontown, outraged citizens used old clothes stuffed with hay to make their own effigies of all 12 jurors, which they then strung up from a large tree next to the railroad track. No one on the passing trains could miss them. (13)

It's not clear where Dukes holed up while all this was going on. Some accounts say he was held in protective custody in the courthouse cells, others that he made it back to his room at the Jennings Hotel and locked the door there firmly behind him. Hearing the mob had given him 24 hours to leave town, he fled at first light, traveling ten miles west to his mother's house in German Township. This is the journey which William Wiggins depicts in his bottle sculpture, showing Dukes' forlorn figure as he flees town. The list of jurors he added to the bottle was clipped from the URS's March 15 trial report.

That same edition of the paper reports that, even on its first ballot, the jury had already dismissed any thought that Dukes was guilty of murder. The votes at that stage stood at two for the lighter charge of manslaughter and ten for outright acquittal. Boyle's arguments that they should disregard Dukes' letters and focus instead on his right to self-defence evidently won out.

The URS - whose R stood for Republican, remember - complained that the jury had been packed exclusively with Democrats and reminded its readers that was the party Dukes himself represented whenever he stood for office. "When the jury was empanelled last Saturday, the defence challenged off every Republican," it said. "True, Republicans generally admitted they had formed an opinion on the matter, but many had not and were challenged solely for their politics. Thomas Searight, clerk of the court and an announced candidate for judge, exhibited a list of the jurors and drew attention to the fact that Dukes was to be tried by a jury solidly Democratic. Shameful boasts were even made by some that 'we have the court and the jury and intend to use them'."

Just in case there were any doubts where its own sympathies lay, the URS ran its report of the Dukes verdict under a nine-deck headline loaded with far more comment than fact:

On March 15, the morning after the verdict, a group of 27 lawyers presented a petition calling for the "infamous", disgraceful" and "unfitting' Dukes to be disbarred from practicing law. The judge gave him till May 10 to present his case against this happening. (14)

That evening, people flooded into Uniontown from all over Pennsylvania to attend what newspapers called an "indignation meeting" to express their disgust at the trial's verdict. Many of Pennsylvania's leading lawyers, doctors, ministers and businessmen were present. They packed into the town's schoolhouse, where Dr Fuller, Uniontown's oldest physician, gave a speech condemning Dukes and the jury in equally fierce terms. Falling into what was now the town's accepted narrative, he expressed firm faith in Lizzie's purity. There were several intemperate speeches from the floor echoing Fuller's view. When the time came to pass resolutions, the meeting accused Dukes and his friends of tampering with the jury and made dark threats about lynch law replacing the courts when juries produced such perverse verdicts as this.

To understand why the rage at Dukes' acquittal was so extreme - and so widely held - we must turn to the legal historian Professor Robert Ireland, who wrote about the case in a 1989 essay. He explains that most US Southerners of the Victorian era took a very particular view of sexual morality and of who should and should not be punished when a challenge to this morality produced violent revenge. He calls this assumption "the unwritten law" and attributes its rise to the fact that so many Americans were then moving from rural areas to embrace city life and the new factory or office jobs that made possible.

This change meant husbands were no longer working alongside their wives, that young single women were able to escape the chaperones their parents' had imposed on them and that young men increasingly had the leisure time and the spare cash to pursue sexual conquests. Not surprisingly, all these innovations led to a good deal of nervousness about the era's morals.

"In order to preserve the stability of society, to ensure the preservation of republican virtue and to retain control over female sexuality, 19th century Americans made women both the guardians and the models of middle-class morality," Ireland writes. "That idea demanded absolute sexual probity on the part of all virtuous women, virginity before and fidelity during marriage. The women who departed from this standard by publicly contradicting the prevailing mores were condemned to a condition of eternal disgrace. If single, they would never have the opportunity of a respectable marriage, if married, they would be cast aside by their husbands; and, married or not, they would be shunned by polite society." (15)

It followed that men in this society had an absolute duty to defend their female relatives' purity and reputation. Where a woman's purity was violated - as Lizzie's appears to have been - her father or brother's duty to confront and punish the man responsible was equally clear. To act in any other way would have been to chip away at the very cornerstone of Victorian morality, which meant juries were very reluctant to convict any man who attacked his sister or daughter's seducer. Men like Dukes were demonised as libertines and even killing them was thought quite justifiable.

"Victorian Americans became so obsessed with the evils of libertinism that they embraced and probably even invented an unwritten law that forgave males who assassinated the despoilers of female sexual virtue," Ireland expains. "In so doing, they [.] seemed to take advantage of an already permissive doctrine of legal insanity that served well the interests of outraged male avengers of female sexual dishonour. A corollary of the unwritten law sometimes forgave those males who assassinated would-be libertines who had merely defamed the sexual honour of a woman."

What this meant in practice was that, confronted with a man accused of murdering his sister or daughter's seducer, the jury would conveniently decide he must have been suffering from temporary insanity at the time and acquit him on those grounds. His sanity now safely returned, the defendant could not be sent to an asylum either. For most people, the correct practical result would then have been achieved - the libertine was dead and the righteous avenger set free.

Dukes' case doesn't quite fit that model, because there it was the avenger who ended up dead. Clearly, though, very few people in Uniontown would have thought Captain Nutt did anything wrong by attacking Dukes in his room or even by coming armed to kill him. For them, Dukes was unquestionably the villain in this whole affair and Captain Nutt had acted in an exemplary way. The unwritten law dictated that Dukes deserved to die for his treatment of Lizzie - whether you assumed that treatment to include impregnating her or not - and the fact that he'd gone on to kill the heroic Captain Nutt just made that verdict all the more plain. Instead, the jury had chosen to let him walk - and that's when the lynch mob started to gather.

Even at his mother's house, Dukes was still within the bounds of Fayette County and far too close to Uniontown to rest easy. Seeing his life was in danger from the mob, his friends persuaded him to write his own detailed account of the fight with Nutt. Even if this account wound up being published posthumously, they argued, it would at least give Dukes a chance to get his side of the story across.

According to Dukes, Nutt had burst uninvited into his room on the fatal night. Here's his own description of what followed:

"[Captain Nutt] did not lift his eyes to mine, but hissed through his teeth, 'I want to see you' and rushed upon me instantly with his cane upraised. I instinctively threw down my head and threw up my arm and the blow fell severely diagonally across the arm. I at once grappled with him and caught the cane.

"We struggled for a few moments about the foot of the bed, and I wrestled the cane away from him and attempted to strike him down with it. He then threw himself against me but the blow had no effect. We were struggling once more and had scuffled over into the corner, back of the bed by the window. I now knew that I was his superior in physical strength and could have drawn my pistol and shot him in the struggle, the pistol being self-acting, but I did not want to kill him.

"I concluded, as I was physically his superior, to do nothing but keep him from hurting me and I cried 'Murder, Murder, Murder' with the full force of my lungs, in order to bring someone to the rescue. As soon as this alarm was given, Captain Nutt called 'Clark! Clark! Clark!' in a much lower tone of voice than that employed by me.

"This call from his nephew, who had accompanied him there, coupled with the threat in his letter of an avenger, filled me with terror and desperation. I instantly threw myself on the cane with all my power, and it was mine. He sprang away from me, back toward the mantel, to avoid another stroke from the cane, and as he went he thrust his right hand into his overcoat pocket and attempted to draw his pistol. It seemed to be entangled.

"I shall never forget the murderous look in his eyes. The awful moment had come. It was he or I. In the twinkling of an eye, my pistol was drawn from my hip pocket, my right foot and arm advanced, the trigger pressed - a flash and Captain Nutt sank down among the wardrobe. My position threw my back toward the door. As Captain Nutt sank down, I heard a confusion behind me."

In Dukes' account, it was only then that Breckenridge, Feather and Williams entered the room. "The statement that Mr Breckenridge or anyone else separated us is positively incorrect," he claims. "I did not know of the presence of any other person in that room other than Captain Nutt and myself when the shot was fired. Captain Nutt was positively not leaning on the mantel when he was shot, His arm was akimbo, his hand clutching his pistol."

In this letter, Dukes also denies statements at the trial that he'd struggled to resist Feather's attempts to take his gun. On the contrary, he says, he'd surrendered both the gun and the cane voluntarily and then immediately walked to the sheriff's office to give himself up. "My mind was in a whirlwind of confusion, but I felt I had been driven to the desperate act for self-preservation and I would submit myself to the law," he writes.

"No man with a shadow of fairness can resist the conclusion that Captain Nutt came to my room on the morning of 24th of December to take my life and that he would have done so had not my dexterity prevented such a result. This conclusion established, then my legal defence is perfect and the attack on the jury is unjust and malicious. [.] I was on trial for the killing of Captain Nutt, not for writing letters."

Let's

pause here for a second to consider the difficult question of whether Dukes' accusations against Lizzie were true.

Let's

pause here for a second to consider the difficult question of whether Dukes' accusations against Lizzie were true.

If we believe the account in his first letter, Lizzie had had full sex with at least one man other than himself, and began fearing she was pregnant when she missed a period at some point in what seems to have been the autumn of 1882. "Unless precautions are duly used, she will become a mother," Dukes writes in his December 4 letter that year. "Just when I am unable to say."

If that pregnancy was real and if it had been allowed to run its full course, then Lizzie would have been about six months gone by the time she granted the New York Times an interview in March 1883. And yet the reporter describes her figure at that meeting as "slender and graceful". Turning to rumours of her pregnancy, he adds: "Her physical condition as indicated by Dukes in his letters is false beyond a doubt". It's fair to conclude then, I think, that whatever Lizzie's condition when Dukes wrote his infamous letter, she certainly wasn't pregnant in March 1883.

That leaves us with several possibilities:

1) Dukes lied about Lizzie ever having been pregnant in the first place.

I'm happy to dismiss this, as it's impossible to imagine any motive Dukes could have had for doing so. Why would any young man of that era tell his girl's father she was pregnant if he knew that wasn't true?

2) Lizzie lied to Dukes when she told him she was pregnant and he repeated that lie in good faith.

Lizzie seems to have had a mischievous streak, so perhaps winding Dukes up in this way was her idea of fun? It may even have been her way of nudging him a little closer to marriage. What's harder to explain is why she'd allow the pretence to persist so long he'd feel driven to alert Captain Nutt.

3) The missed period was a false alarm, but Lizzie for some reason never passed this news on to Dukes.

Women of Lizzie's age and class had very little sex education in the 1880s, so it is possible that she was simply mistaken when she concluded she was pregnant. But why wouldn't she have set Dukes straight when she realised the emergency was over?

4) Nature intervened and Lizzie's pregnancy never went to full term for that reason.

Even today, around 20% of pregnancies naturally miscarry in the first 20 weeks. The rate would surely have been higher in Lizzie's day.

5) Lizzie deliberately brought the pregnancy to an end by medical means, perhaps with the help of her mother.

By 1880, most abortions were illegal in the US, but of course they continued nonetheless. American doctors in the 1890s estimated there were then two million such operations carried out in the US every year. Home remedies were available too, in the form of the abortifacient pills discretely advertised in the Victorian press. Lizzie may have taken this option to preserve her good name and her prospects of a respectable marriage. If so, the family's money would at least have spared her the horrors of a back street procedure. (16)

6) Lizzie actually fell pregnant a little earlier than I'm assuming and had already given birth by the time of the NYT interview.

Dukes' letter gives no specific dates for any of his meetings with Lizzie, which means we can't rule out the idea that she'd fallen pregnant as early as April or May 1882. That makes it just about possible that she could have secretly given birth in February 1883, given the baby away immediately and regained her figure in time for the NYT interview. For that to be true, though, we'd have to believe Dukes waited six months before alerting Captain Nutt to his daughter's condition - and why would he do that?

A secret birth and secret adoption would also have been very complicated to arrange and even harder to prevent people gossiping about when the family was under such close scrutiny. There's no sign of an unexplained child appearing anywhere in the Nutt family at this time, so Occam's razor dictates this theory can be dismissed.

For my money, items four and five on the above list are those which strain credulity the least. The fact is, though, that we'll never know for sure, so feel free to make your own choice.

Now let's move on to the question not of Lizzie's pregnancy, but of her supposed promiscuity. It's interesting that Captain Nutt never denies Dukes' charges against his daughter when replying to that infamous letter. Indeed, he makes it very clear that Dukes' only honourable way out of this situation is to marry Lizzie. We shouldn't assume from that that he'd confirmed Lizzie was pregnant, though.

In the Victorian age, merely losing her virginity was enough to bar any single girl from finding a respectable marriage, and to make that girl's father insist on a shotgun wedding. The letter's suggestion that Lizzie was already the object of salacious gossip among Uniontown's young men made matters even worse. Pretty clearly, nothing she'd told her father when he questioned her about the letter's allegations had been able to put his mind at ease. Dukes' assertion is that it was Bogardus who took Lizzie's virginity, not him, but perhaps Captain Nutt was just too angry at the letter to bother with such fine distinctions.

The other young men of Uniontown who Dukes mentions in his letter were quick to spring to Lizzie's defence - though perhaps only because they wanted to save their own skins. Frey, Kennedy, Hagan and Bogardus all issued statements to the newspapers describing Lizzie as the most modest and chaste young lady any gentleman could wish to meet. Anything less than that, and they may have found their own effigies dangling from the town's telegraph poles.

Lizzie herself denied all Duke's charges too. "There is not a word of truth in any of Mr Dukes' letters," she told the NYT. 'What induced him to write them, I cannot imagine, unless his object was to manufacture an excuse for breaking our engagement. [.] Everyone has been deceived by him and I most of all. We had been engaged several months. He was a constant visitor here and was cordially received by the whole family. I did not suspect that he wanted the engagement broken. Why didn't he tell me?"

It's a good question - but here's an even better one. If all Dukes wanted to do was end the engagement, then why try to do so by writing her father such an extraordinary letter? Surely he'd have been able to see that, far from extricating himself from an unwanted engagement, a letter like that could only land him deeper in the mire? (17, 18)

"Then he wrote those vile letters to father," Lizzie continues in her interview. "All the world knows the rest. I would rather have died than that this misery and disgrace should have fallen on my mother and her family. But indeed, sir, I am innocent of each and every charge brought against me."

I'm a little sceptical about Lizzie's protestations here. My guess is that she was really an adventurous and somewhat mischievous young woman who sometimes went a little further with her admirers than polite society would then have condoned. The fact that Captain Nutt was so often away in Harrisburg probably made these liaisons a little easier for Lizzie to arrange. There are several hints in the press coverage that he treated Lizzie with great indulgence, which suggests that - like most daughters - she had no difficulty in twisting dear old dad round her little finger.

If Lizzie had admitted any part of Dukes' accusations, she would have disgraced her family and scuppered her own marriage prospects. The newspapers had already decided that the way to maximise this story's impact was to paint Dukes as a foul traducer of innocent womanhood, and this narrative demanded they present Lizzie in the most saintly light imaginable. That was the story people wanted to believe, which helps to explain why the initially rather stand-offish families of Uniontown society rushed to invite Lizzie round for tea after the trial's conclusion. By issuing these invitations, they signalled that they were happy to welcome her back into their ranks and rally round the consensus tale the newspapers had already adopted. Anyone stepping out of line to offer a more critical view of Lizzie's behaviour risked falling foul of the mob.

Dukes never disavowed the contents of his December 4 letter, but he did come to regret writing it. "I foolishly thought I was doing Captain Nutt a cruel kindness and taking a stand for the preservation of my own honour,' he said after the trial. "Since this occurred, I have concluded that honour is a delusion and a mockery. My enemies teach that the whole matter was a deep-laid scheme: that I deliberately ruined the daughter and then killed him. What motive could I have for such a scheme?

"When I wrote that first letter to Capt. Nutt I committed a most appalling blunder. It was the personification of stupidity and the remorse of a lifetime will be inadequate expiation for the error. When I look back upon it in the light of developments, I can scarcely resist the conclusion that I was labouring under temporary insanity."

One day in 1908, a hobo named Carl Worner walked into Maier's Saloon on Shenandoah Avenue in St Louis and offered to make the owner a whimsy bottle in return for a hot meal and a couple of free drinks.

One day in 1908, a hobo named Carl Worner walked into Maier's Saloon on Shenandoah Avenue in St Louis and offered to make the owner a whimsy bottle in return for a hot meal and a couple of free drinks.

"He would ramble from bar to bar, calling for a large bottle, cigar boxes, scrap wood a hairpin and glue," says Missouri State History's Andrew Wanko. "From these, he would produce a vibrant miniature scene in a bottle in exchange for food and drink at the bar." (19, 20)

The bottle sculpture Worner produced that day depicts the interior of a typical saloon. It shows the owner and his black waiter serving three customers who are standing at the bar, each with a drink in his hand. In the foreground, Worner's added a couple of tall, spiky shrubs and a barrel of Klausmann beer. Above the whole scene, there's a carefully lettered "Saloon" sign and some decorative woodwork, topped by two crossed American flags.

Klausmann Beer was a real brand, brewed in the nearby St Louis neighbourhood of Carondelet and presumably on sale at Maier's. Wanko guesses it won its place in the bottle either because it happened to be the saloon's top seller, or perhaps simply because Worner liked it more than any of the other beers on offer there. (21)

"This saloon in a bottle has a personal connection for me, even though I've never seen the saloon owner or met the man who spent a full day working his art into shape for a salty cut of meat and a few beers," Wanko wrote in 2014. "Maier's saloon was located at 3200 Shenandoah in the present day Tower Grove East neighbourhood. The building still houses a bar, Van Goghz, [where] I watched the Cardinals win the 2011 World Series."

The waiter in this bottle is the only black person Worner seems to have included in any of his bottle sculptures. He's carrying a large sliced ham, a common part of the cheap (or even free) lunches which many saloons then supplied for anyone buying a drink. "St Louis reputedly had some of the best saloon lunches of any city in the country," Wanko's MHS colleague Anne Woodhouse wrote in a 1999 article. "The sliced ham was probably a frequent lunch offering at the Maier saloon, perhaps on alternate days with Christine Maier's noodle soup. Both these dishes are salty and would have encouraged the sale and consumption of beer to wash down the meal." (22)

"Carl Worner would never have considered himself a historian, but in a way that's what he was," the folk art expert Allan Katz told me. "His depiction of various bars and commercial establishments are most likely extremely accurate and become a snapshot of these neighbourhood bars and saloons. His bottle sculptures capture the spirit of an itinerant artist. They were created at a very romantic time in history, when America was swelling with a new immigrant population and reflect how these immigrants were changing the American cultural landscape." (23)

We have many other examples of Worner's whimsy bottles, most of which he produced for various bars in the Midwest between 1900 and 1920. His nomadic life took him to Chicago (where he produced bottles for saloons owned by John Neubauer, Frank Bolit and Sven Mellin), Granite City (the HC Meyer Saloon) and - as we know - St Louis (Maier's Saloon, Henry Eiler's Saloon, Frank Behren's Saloon). He seems to have spent most of time in Illinois and Missouri, though we also have two bottles produced in Newark, New Jersey, for saloons there owned by men named Salzman and Rummel.

"His only request was for a cigar box and an empty bottle," Illinois' The Living Museum magazine says of the Granite City bottle. "He cut pieces from the cigar box, coloured them and glued them in place with a long hat pin. The saloon-in-a-bottle was presented to Meyer in exchange for a few free drinks." Unlike ships in bottles, which are built outside the bottle and simply have their masts' raised inside, Worner constructed his whole sculpture inside the bottle, using that long hat pin to reach any area he needed to work. (24)

"His works are generally much more complex, colourful and capable of being researched [than other bottle art pieces]," Katz told me. "When I first came upon a Carl Worner bottle, my reaction was, 'This is a fairly complex piece and there must be more to discover'. Before long, you see another and know that it was made by the same person. Both collectors and historians are intrigued by being able to piece together the storyline of a person's life by reviewing their body of work."

Most of Worner's bottles are now owned by private collectors. In a 2010 PBS episode of The Antiques Roadshow, one guest presented Katz with a Worner bottle which her father -in-law had won in a Chicago saloon's card game at some point in the 1930s. This bottle combined Worner's typical saloon scene with an old German folk tale called "Die Sieben Schwaben" (The Seven Swabians). Katz put its value at $3,000 to $4,000. "Worner's bottles fit perfectly into the Folk Art marketplace," he told me. Holding a piece of wood in your hand and carving it is a timeless folk tradition that has existed in every culture in the world. (ix)

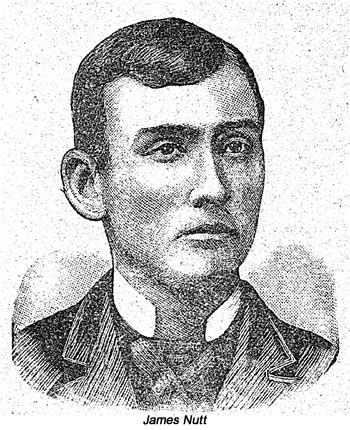

Bythe end of March, Dukes was back in Uniontown and once again living at the Jennings Hotel. He refused to leave even when some delegates from the town's indignation meeting called round to demand he packed his bags. Determined to ride out the town's remaining bad feeling against him, Dukes began carrying a gun everywhere he went, telling friends he would not hesitate to kill anyone who attacked him. One threat worried him more than any other. "Although many in the area had expressed their belief that Dukes should be lynched, the only man whom he said he feared was James Nutt, the twenty-year-old son of Adam Nutt," Ireland writes. (26)

Bythe end of March, Dukes was back in Uniontown and once again living at the Jennings Hotel. He refused to leave even when some delegates from the town's indignation meeting called round to demand he packed his bags. Determined to ride out the town's remaining bad feeling against him, Dukes began carrying a gun everywhere he went, telling friends he would not hesitate to kill anyone who attacked him. One threat worried him more than any other. "Although many in the area had expressed their belief that Dukes should be lynched, the only man whom he said he feared was James Nutt, the twenty-year-old son of Adam Nutt," Ireland writes. (26)

Dukes was not the only one who thought James Nutt might try to avenge his father. Charlotte Nutt was concerned enough to press her son to promise he would never do such a thing, but James refused to give her any such assurance. He was angry about his father's death and constantly brooding on the town's vengeful expectations. Surely a dutiful son in these circumstances was honour-bound to make Dukes pay for his father's slaying in blood? And yet, here the killer was, blithely walking the streets of Uniontown where James could hardly avoid encountering him every day. (27)

According to the Quebec Daily Telegraph, James returned home to his mother in a foul mood one day in June. "I can't stand this, " he told her. "I met Dukes on the street today and he laughed in my face." From that day on, the paper adds, Mrs Nutt feared the worst - and a few days later, all her fears were realised. On June 13, 1883, James was walking along the street in Uniontown with Al Miner, the local newspaper's court reporter. Dukes' appeal hearing against his likely disbarment from practicing law was then just two days away, and that's evidently what he had on his mind. (28)

"Dukes, seeing them coming, walked out and in a very offensive way called out to Miner, 'Have you got all the testimony written out in the case against me?'," the New York Times reports. "Nutt stood with his head bowed while Dukes insolently called up a feature of the legal proceedings that bore directly upon the murder of his father and the attempted degradation of his sister. [.] The youth seemed in deep thought all the way home as he and Miner walked along. It was after these repeated insults, together with a growing belief that Dukes would still be permitted to disgrace the profession to which he belonged and also to insult the general sentiment of the community by his presence, that the fatal resolve took possession of him." (29)

After the Dukes trial, Clark Breckenridge had given James the Colt .32 revolver Captain Nutt carried on the day he died. Returning home, James placed a target board against the carriage house wall, then moved a few yards away and began firing rounds into it from his father's gun. Two of his uncles joined this target practice, one of whom was heard urging him not to fail in the task he planned.

James then returned to Uniontown and concealed himself in the shadows of a wrecked storefront, just opposite the corner of Main Street and Pittsburgh Street, where Uniontown's Post Office stood. His chosen spot was an old drugstore, the front of which had been torn off as part of redevelopment plans. James seems to have arrived there about 7:00 o'clock in the evening and to have known that Dukes generally called at the Post Office to collect his mail around that time.

As James took up position, Dukes was chatting amiably to some friends outside the Jennings Hotel. At about 7:10pm, he said his goodbyes and set off to walk the single block to the Post Office, a route which would take him straight past the derelict drugstore. Dukes was dressed in a dark suit and hat, with a high-collared shirt and a black cravat, swinging his jaunty rattan cane as he walked. Here's the NYT's account of what happened next:

"When Dukes reached the spot, or got a little beyond where he stood, Nutt opened fire on him and shot twice in quick succession, the balls striking Dukes in the back, immediately behind the heart. Dukes started on a dead run and was pursued by Nutt who fired three more shots at the fleeing murderer.

"One of these took effect in the back, only about two inches from the first two, another simply went through Dukes' coat without wounding him and the fifth and last struck his left ankle as he was going up the Post Office steps. There were two steps to go up into the office and when Dukes reached the top one, he fell forward on his face.

"There was an immense crowd of people standing around on the outside of the office and they ran in every direction for fear of being shot. The fifth ball only grazed [Dukes'] left ankle and glanced off and went through some lock boxes.

"A number of persons rushed up the steps when Dukes did. At the same time, Policeman Pegg ran up and caught Nutt, who made no resistance whatsoever, but said to the officer, 'Here, you take this,' as he gave him his revolver. Pegg said to him, 'You have done a bad piece of work'. To which Nutt replied, 'Yes, but I could not help it'." (30)

Pegg arrested Nutt there and then, placing him in the town jail under Sheriff Hoover's supervision. By the time Hoover turned the key, crowds were already gathering round Dukes' body. "People rushed to the scene of the shooting by hundreds," the NYT reports. "It was all that a dozen men could do to keep the immense crowd from the body. There were one or two cries of 'Stand back and give him air' and many shouted: 'He needs no air. Let him die, he got what he deserved'. [.] The universal feeling is that James Nutt did perfectly right."

Amid all this chaos, a man called Lingo tried to speak to Dukes as he lay on the ground, but got no more than a few weak gasps in reply. Within a minute of the last bullet striking him, Dukes was dead. Eyewitnesses said they'd seen him turn round when the first shot was fired and stare James straight in the face for a second before breaking into his run. Another mentioned how ashen Dukes' face had looked when he'd glimpsed it fleeing past. As soon as some semblance of calm was restored, Dukes' body was taken back to the Jennings Hotel, where he was laid out in the same room where Captain Nutt had died just six months earlier.

The same unwritten law which had wanted to see Dukes hanged for Captain Nutt's killing now demanded that James Nutt must escape punishment for murdering Dukes. "Several leading newspapers declared that Nutt had shot Dukes 'down like a dog' and accompanying stories joyfully proclaimed widespread public approval," Ireland points out. "Editorials throughout the country cheered the death of a 'monster', a 'moral leper' and a 'miserable wretch', arguing that James Nutt had properly invoked the unwritten law."

Lizzie Nutt was quick to applaud her brother's actions too, saying she'd have done the same thing herself if given half a chance. One newspaper reported that she, like James, had been practicing her marksmanship at the family farm for several months and that it was revenge against Dukes which both siblings had in mind.

Southern newspapers, which had long ago grown sick of Yankees lecturing them about Dixie's brutal jurisprudence, were quick to crow about the embarrassment this case was creating for their northern neighbours. The Atlanta Constitution said Dukes' acquittal had been the most "complete failure of justice" in US history adding that, if Captain Nutt had been a Southern gentleman, he would have killed Dukes straight away and hence saved his son the trouble. The Louisville Courier-Journal declared that any Southern jury would have convicted Dukes without a second thought, again bringing the matter to a speedy end.

Even the stately New York Times accepted that attacking Dukes was the only honourable choice James had been left with. "It is because all men share and almost all men justify this feeling and consider the duty it imposes more urgent than even the duty of being a law-abiding citizen that Nutt is not in the slightest danger of losing his life or even his liberty," the paper said in its June 15 editorial. "There is no ignoring the plain fact that public sentiment will acquit him and no ignoring the equally plain fact that, before the law, he is guilty of a crime punishable with death."

However predictable the outcome might seem, still the full procedure of the law had to be gone through. Doctors examining Dukes' body found four bullet holes in the back of his coat, all gathered on the left-hand side, together with some corresponding holes in the back of his waistcoat. He had a short knife, designed for stabbing rather than slashing, hanging from one of his trouser buttons and the revolver he'd used to kill Captain Nutt in his right hip pocket. Neither weapon had helped him at all when the attack finally came.

The coroner's inquest, which began next day, found that only three of James's five bullets had entered Dukes' body, all targeted closely at his heart. One bullet had fractured a rib and another had moved past his backbone to puncture a lung and then lodge in his heart's right ventricle. The NYT invited its readers to admire James's marksmanship, noting with approval that he'd placed the three entry wounds so closely that a ring no more than four inches in diameter would cover them.

Although the three bullets in Dukes' body were safely recovered, the remaining two could not be found. Most likely, they were scooped up by souvenir hunters. Word of the killing had got round all the surrounding hamlets by now, bringing many curious rural visitors into Uniontown, where they soaked up every detail from the inquest and eagerly questioned the town's residents.