A few years ago, I found myself with an afternoon to kill in San Francisco, so I set off through Chinatown to find myself some Hell money.

A few years ago, I found myself with an afternoon to kill in San Francisco, so I set off through Chinatown to find myself some Hell money.

I was looking for the fake banknotes which Chinese people burn at funerals or beside a grave to ensure their lost loved one has plenty of spending power in the afterlife. I started my quest in the tourist shops lining Grant Avenue, but quickly hit a snag. All the young Chinese-American people I found there spoke flawless English, but had no idea what I was talking about when I asked if they sold Hell money. The alternate terms "ghost money" and "spirit money" produced an equally baffled response.

Even where Hell money did seem to ring some kind of vague bell, the young people I questioned had no interest in the subject, and clearly couldn't understand why anyone would be curious about it. I tried approaching one or two of the older people I found in the same shops, but their English didn't stretch much beyond barking the price of various goods at potential customers, so I had no luck there either.

At the fifth or sixth shop, just as I was ready to give up, I found a charming young teenager who went to fetch her grandfather for me, and stood there translating back and forth as I explained what I was looking for. His face cracked into a big smile at how daft gweilo tourists could be, and between the two of them they directed me to a store about seven or eight blocks away. This took me well away from Grant Avenue's main drag to a backstreet where only the area's native Chinese population went to shop.

The store was the size of a large living room, and staffed by an elderly Chinese man. When I think of it now, I remember a dark interior with dust mites dancing in the odd bit of sunlight that managed to find its way in. The place was crammed with display gondolas, each groaning beneath of the weight of goods piled higgledy-piggledy on its shelves. In the back corner, I found a section packed with bundles of Hell banknotes in eight different designs. Each bundle was held together with a cellophane band, and contained about 30 or 40 identical notes. This was in 2004, when the cheapest bundle was priced at 35c and the most expensive at 50c. (1)

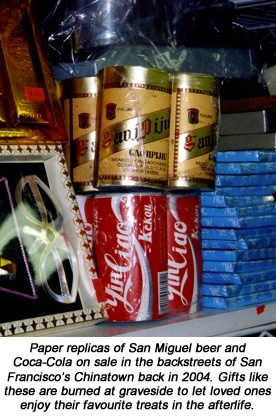

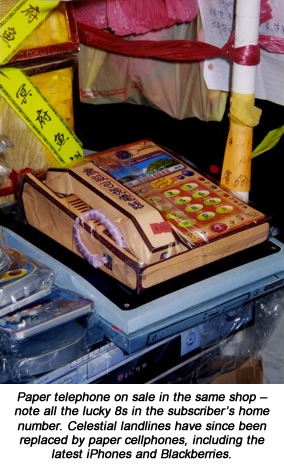

Next to the notes, I found a display of the paper replica goods Chinese people also burn at funerals, again with the idea of "transmitting" them to loved ones in the afterlife. At this particular shop, mourners could find paper telephones, games consoles, cigarettes and jewellery. I took a few photographs, then made my selections and took them up to the counter. The old boy there clearly thought I was mad as well, but we got through the transaction with a mixture of smiles and benevolent nods, and that's how I came by most of the banknotes and all the paper replicas you'll see illustrating this piece.

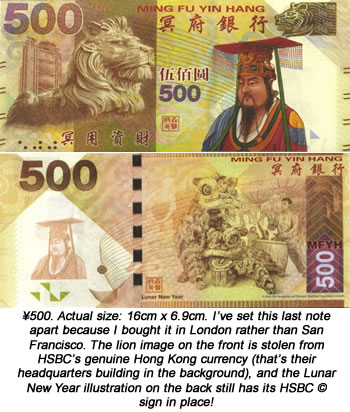

A few months later, I repeated the process in London's Chinatown, again finding it was only the smaller, slightly tattier, shops that could help me. I didn't find any paper replicas in London, but I did add a few new Hell notes to my collection, an example of which you'll find at the end of this article. One day, I hope to find a Hell note denominated in British sterling or (better yet) in Euros, but I haven't managed it yet.

"Hell money is usually made in Hong Kong, China or Vietnam for the local market," banknote dealer Joel Anderson told me. "Hong Kong uses dollars, and for a long time the US dollar was the preferred currency in the Far East, so most Hell notes are still denominated in dollars. For a long time, the Chinese yuan was not convertible, so I guess they figured it wouldn't do them any good when they got to Hell." (2)

Hell money springs from a very old tradition in Chinese culture, arguably stretching back as far as 1600 BC. Archaeologists have found tombs of that era in China with imitation metal money placed among the human remains. China has been using some form of paper money since the 9th Century, and paper money's been dominant there for nearly 800 years. Joss paper copies of this money have been burned at funerals and graves for almost as long, and some people still prefer to use this form of spirit "cash" in paying their respects today.

Hell money springs from a very old tradition in Chinese culture, arguably stretching back as far as 1600 BC. Archaeologists have found tombs of that era in China with imitation metal money placed among the human remains. China has been using some form of paper money since the 9th Century, and paper money's been dominant there for nearly 800 years. Joss paper copies of this money have been burned at funerals and graves for almost as long, and some people still prefer to use this form of spirit "cash" in paying their respects today.

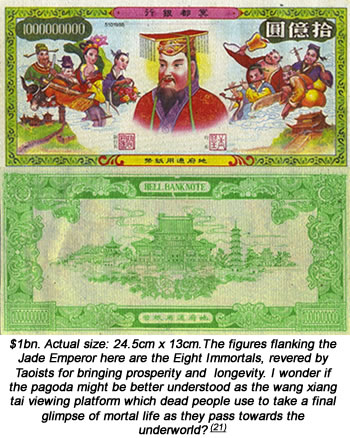

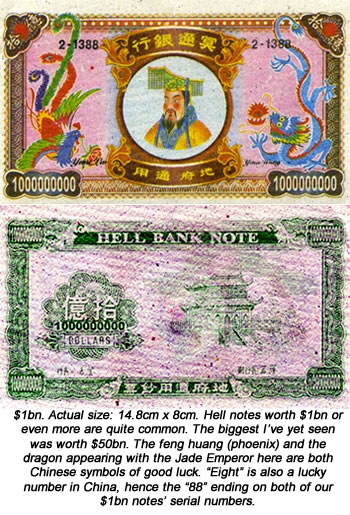

The first Chinese currency resembling a modern banknote was printed around 1890, and it's reasonable to assume that Hell's currency appeared soon after. "The earliest Hell notes I've seen that look like banknotes were printed in the mid-1930s," Anderson told me. "In the past decade or two, they have become increasingly elaborate and colourful." When hyperinflation gripped China in the 1940s, Hell banknotes followed suit, producing the denominations of $1bn, $5bn or even $50bn we see today.

The name "Hell money" is thought to derive from a misunderstanding between the first Christian missionaries to reach China and the people they tried to convert there. Thinking "Hell" meant merely the afterlife in general, rather than the zone it sets aside for evildoers alone, Chinese people were happy to use this word on their dead relatives' offerings. The habit's stuck ever since, with a dozen "Hell Money" designs appearing for every one which labels itself "Heaven Money" instead. For Western collectors like me, this has the added appeal of giving the notes a sexy, badass name which "Paradise Money" or "Afterlife Money" simply can't match. (3, 4)

The Chinese concept of the afterlife is that the dead person's spirit lives on, doing much the same things it did in life. It follows that money will be needed to buy all those little treats that make death worth living, as well as the occasional gift like the consumer goods I found in San Francisco. Sometimes, the hope is that sending your loved ones cash in this way will help to speed their progress through the afterlife's various stages to a happy reincarnation. This can be achieved either by supplementing the offerings they made in life to atone for their sins, or simply by bribing the spirit world's ruling administrators. (5)

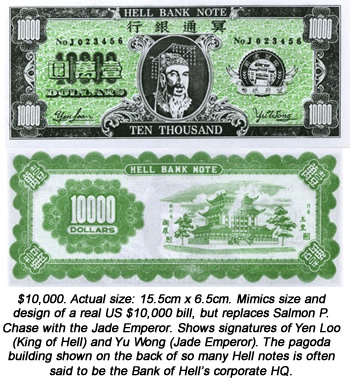

Chief among these are Yu Huang, also known as the Jade Emperor, and Yan Luo, the King of Hell. Their twin signatures appear on many of these banknotes, though the Romanised spelling often varies.

Yu Huang was a wise and kindly Chinese leader whose good deeds in life and cultivation of his Tao won him immortality. When he defeated a terrible demon who was set to take over every realm of existence, the gods rewarded him by giving him command of what Christians would call Heaven, Hell and the mortal world. Yu Huang delegated part of these duties to Yan Luo, who presides over Diyu. Everyone has to go to Diyu when they die, where Yan Luo's first job is to judge whether their next stop should be the Taoist version of Heaven or Hell. It's this decision - or perhaps the length of a stay in Hell/Limbo - which people hope to influence when they offer Yan Luo these banknotes as a bribe. (6)

Almost all the Hell notes I've seen use a Yu Huang portrait showing him in his trademark flat hat with the beads dangling from it. He's generally placed where a US President would appear on American currency, or the Queen on a British banknote. Most of the other images used, as I've detailed in the captions, are good luck symbols of one kind or another: a fish, a phoenix, a dragon and so on. Hell notes are mostly found in Cantonese areas throughout Asia, and draw on both Taoist belief and Chinese folk religion for their customs and imagery. (7, 8)

Almost all the Hell notes I've seen use a Yu Huang portrait showing him in his trademark flat hat with the beads dangling from it. He's generally placed where a US President would appear on American currency, or the Queen on a British banknote. Most of the other images used, as I've detailed in the captions, are good luck symbols of one kind or another: a fish, a phoenix, a dragon and so on. Hell notes are mostly found in Cantonese areas throughout Asia, and draw on both Taoist belief and Chinese folk religion for their customs and imagery. (7, 8)

The Chinese characters on the notes say the same sort of things as the English text, mostly just giving the note's value or naming its issuer as some variety of Hell Bank.

Some notes go a step further, and blur the line between innocent parody of a real banknote and something more like deliberate forgery. "The Chinese printers often copy images and names from legitimate bank notes to make the Hell notes more authentic," Anderson told me. "One of my favourites copied a US $100 bill, changing only the legend on the back. Understandably, the US Secret Service was not too pleased, and that issue seems to have been discontinued."

You can see the $100 Hell note Anderson has in mind here, where it's wrongly described as movie prop money. These notes were produced in Vietnam in the late 1990s or early 2000s, and the only change they make to the genuine $100 bill is replacing the words "The United States of America" with "Ngan Hang Dia Phu" on the reverse side. This translates as "Bank of Limbo". (9)

Among my own collection, the note that comes closest to a forgery is the ¥500 note below, which takes almost all its imagery from genuine Hong Kong banknotes like this one.

China's currency designers have suffered their share of theft too. The image of the Hukou waterfall shown on the back of my ¥50 Hell note, for example, is lifted from China's genuine ¥50 note. The long flat building shown on the back of my red ¥100 Hell note is China's Great Hall of the People, and the image itself is lifted from China's real ¥100 note. Even the use of four Jade Emperors on my blue ¥100 Hell note seems based on the genuine ¥100 note's design, which shows four former Chinese leaders in a similar arrangement. (10)

With this degree of detailed copying in their design, it's small wonder some people mistake Hell notes for genuine currency. "A few years ago, I got a phone call from someone in India who had a high denomination Hell banknote and wanted to know how to contact the bank to redeem it," Anderson told me. "I tried to explain that it was not a real banknote, but was printed for use by dead people.

"He did not grasp the concept, and a few minutes later his wife called with the same question. Again, I tried to explain that Bank of Hell did not exist. I added that the money could only be used by dead Chinese, but she too did not grasp the explanation. They were convinced that they had a real banknote that could be redeemed by some bank in China or Hong Kong."

Searching for paper replicas of consumer goods in San Francisco, I found nothing more exotic than the beer, jewellery and electronic items mentioned above. But these just scratch the surface of what a dead loved one can receive.

Searching for paper replicas of consumer goods in San Francisco, I found nothing more exotic than the beer, jewellery and electronic items mentioned above. But these just scratch the surface of what a dead loved one can receive.

At the luxury end of the market, people also burn paper replicas of gold and platinum credit cards, travellers' cheques, laptop computers, passports, airline tickets, luxury villas with manicured gardens, Mercedes limousines (some complete with a liveried chauffeur), sub-zero refrigerators and even domestic servants. Often, these elaborate paper models are commissioned specially to reflect not only the family's wealth but also the dead individual's own preferences and style. The British Museum's Living and Dying exhibition has a particularly nice example in this rather beautiful paper motorcycle from Malaysia. The same show has photographs of a Penang family burning a life-size paper Mercedes in order to deliver it to one of their own dead relatives.

China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Vietnam and Malaysia all have specialist Gods Material Shops, where a wide range of paper replicas and Hell notes can be bought by grieving relatives. Some are keen to ensure the deceased enjoys not only the normal consumer comforts, but a healthy sex life too.

In April 2006, China Daily reported that Dou Yupei, deputy secretary at the Ministry of Civil Affairs, had introduced fines for anyone found burning "vulgar" items at graveside. Among the examples he complained of were paper models of condoms, Viagra tablets and the bar girls hired to pamper men at expensive nightclubs. Some families had even been found burning paper dolls representing the "Supergirls" made famous by China's version of America's Got Talent. (11)

"Not only is [this custom] mired in feudal superstition, but it just appears low and vulgar," Dou said. He asked people to make their tributes online instead, but this suggestion was widely ignored. A year later, the Nanjing Morning News was condemning the sales of paper Viagra tablets all over again. "The people who make this stuff are definitely lacking in taste and civilisation," it quoted one reader as saying. (12, 13)

Mao tried to wipe out the custom of burning paper offerings in graveyards too, but even he never quite succeeded in doing so. Tomb Sweeping Day, the annual festival when Chinese families tend to their loved ones' graves, was banned under communism, but reinstated as a public holiday in 2008. That's still the day when a lot of Hell notes get burned. Some families stack them in loose piles on the grave before setting a match to them, while others fold them into intricate patterns to distinguish the Hell notes from real cash. A third group burn Hell notes alongside their paper replica gifts, believing the money will distract evil spirits who would otherwise intercept the burned gifts for themselves. (14, 15)

For those unable to travel to their own family graves on Tomb Sweeping Day a convenient patch of waste ground is pressed into service instead. "In the evening, the street corners all over town will light up as people make small fires to burn the Hell money and things to send their ancestors," Joann Pittman, an American teacher living in Beijing, reports. (16)

At funerals, it's also acceptable to place Hell notes intact in the loved one's coffin, or simply to release them into the wind so they'll waft to the afterlife that way. Some families distribute Hell notes to mourners as they arrive at the funeral for just this purpose. (17)

Although many young Asians continue to use Hell notes today, they generally do so out of respect for family tradition rather than any literal belief in the notes' power.

Although many young Asians continue to use Hell notes today, they generally do so out of respect for family tradition rather than any literal belief in the notes' power.

That's certainly what a group of anthropology students found when they interviewed a young Vietnamese woman burning Hell notes at a Taoist temple in California. Their interview also gives an intriguing glimpse into how different generations of the same family view this custom. This became clear from the students' very first question: "What is Hell money?"

"It's not Hell money, it's Heaven money," the young woman replied. "My dad got mad at me for calling it Hell money. (18)

"I personally don't believe in Heaven money and all the other stuff that goes along with it, but I know it meant a lot to my Grandma, so I was mainly doing it for her and other members of my family. All I know is that my mom made me do it, and she told me the money floated up to Heaven for Grandma to use."

At this point, the young woman's mother came over to see what was going on, and the students were able to interview her too. "I have done the same thing my parents and their parents did before," she explained. "We pray for the dead person to give us good luck and good health. We burn Heaven money and paper clothes on the anniversary of the death. Burning Heaven money is mostly religious, but it can be somewhat of a cultural thing also. They use the money to buy a Prada suit or something." (19)

The other young people burning Hell money at the same temple gave very similar answers to this woman's daughter, placing them more in the cultural camp than the mother's religious one. For those without this family's traditions to follow, popular culture such as gaming or TV may provide their only encounter with Hell money. The 2012 video game Sleeping Dogs: Murder at North Point, for example, asks players to collect Hell money from various hidden shrines in Hong Kong. The game itself pits cops against supernatural gangsters, so you can see how Hell notes fit its theme.

The X-Files has used these banknotes in one of its own plots too. In the season three episode Hell Money, Fox Mulder finds the charred remains of a Hell note on a murder victim's body in San Francisco's Chinatown, and it provides a vital clue. Told by local detective Glen Chao that only a few shops in Chinatown sell the Hell money - a fact I can vouch for myself - Mulder replies: "That's good. Maybe we just found a way to identify the body." (20)

Nielsen ratings show this particular episode of The X-Files was watched by close to 15m people on its first airing alone, giving Hell notes what's almost certainly their biggest exposure yet to a mainstream western audience. Factor in repeats, syndication and video/DVD sales too, and that number would be much, much higher.

I've also seen pictures of Hell notes featuring actors like Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart and James Dean. Another set concentrates on dead world leaders, presenting the unlikely quintet of John F Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and Ho Chi Minh.

To see many more photographs of Hell notes and other paper offerings, please visit the PlanetSlade pages here.

Sources & Footnotes

1) Despite the wide variety of Hell notes available, there's very little interest in them among banknote collectors. They've yet to be documented in any properly organised catalogue, which may explain why they're still so cheap to buy.

1) Despite the wide variety of Hell notes available, there's very little interest in them among banknote collectors. They've yet to be documented in any properly organised catalogue, which may explain why they're still so cheap to buy.2) Exchange of e-mails, June 2013. Joel Anderson's site for collectors of coins and banknotes is here: http://www.joelscoins.com/.

3) I suspect it's the notes' badass name which appeals to the good folks at Planet Voodoo (no relation). They suggest adding Hell notes to mojo bags in order to draw money to you, using them as "bribes to the Dark Spirits" when practicing necromancy or incorporating them into your crossroads or graveyard rituals: http://www.planetvoodoo.com/voodoo-temple/hell-bank-note-ritual.htm.

4) The Chinese folk healer called a hoat-su uses Hell notes in his own magic rituals too. He stamps the notes with characters describing the problem at hand, then burns them and stirs the ashes into a cup of water. When he's taken a sip of the water and spat it out again, the problem's gone too.

5) Hell notes can also be burned at the Hungry Ghosts Festival, when the dead return to visit their living relatives. This is thought to appease the ghosts with no families of their own, who would cause mischief otherwise. Capturing Penang has this photo: http://www.capturingpenang.com/2010/08/hungry-ghosts-returning-to-hell.html.

6) Diyu translates as something like "underground hold" or "underground court". It's both the afterworld's holding cell and its courtroom.

7) According to Wikipedia, over 450m people around the globe practice Chinese folk religion, accounting for about 6.6% of the world's population. China Consumers' Association figures reported here say the nation spends over ¥10bn (about $1.6bn) of real money on paper funeral goods every year. The most expensive single item CCA found was an elaborate paper villa priced at ¥16,888 (about $2,700).

8) Other creatures you'll see on Hell notes include the foo dogs whose statues guard public buildings in China and the ch'i lin, a hybrid creature from myth which is said to appear when a great leader dies.

9) Joel Anderson told me the only other currency he's ever seen used on a Hell note besides yuan and dollars is the Vietnamese dong. Many of the earliest Hell notes seen in the USA were brought home by soldiers who'd fought in the Vietnam War.

10) You can see the real Chinese notes on this China Today page and their Hell money copies here.

11) As with any other TV show, this programme's sponsors were keen to see their company name included in the show's title. Rather wonderfully, this has led to the show being called Mongolian Cow Sour Milk Supergirl.

12) China Daily, April 25, 2006.

13) Daily Telegraph, March 22, 2007.

14) Burning real money, even in small denominations, is considered bad luck in China.

15) In still another tradition, Hell notes can be piled neatly on to a relative's grave and left there intact as a simple offering. A photo appears on Joann Pittman's blog page below.

16) Outside-In, by Joann Pittman: http://joannpittman.com/chinese-culture/2012/hell-money/

17) I've also read accounts of mourners who like to retain one Hell note from every funeral they attend, presumably as a remembrance of dead friends. I've no idea if this is a widespread custom or not.

18) This interview was conducted by students at the University of California in Irvine. You can find their full report here: http://www.anthropology.uci.edu.

19) It's official: the Devil really does wear Prada!

20) The X-Files: Hell Money, written by Jeffrey Vlaming (Fox). Season 3, episode 19. First aired: March 29, 1996.

21) I put this idea to the British Taoist Association. "I rather like your suggestion," Shidao replied. "Pagoda-style structures are often used to mark a significant location and provide a place for seeing further into the distance - surely good attributes for a wang xiang tai."