Bob Zabor was just two minutes into his live Peel session as Jawbone when disaster struck. “My bass drum broke in the first song,” he told me from his home in Detroit. “The strap on the pedal broke. Fortunately, I was prepared. I had a bunch of tools ready because I didn’t want anything to go wrong. I was able to fix it in about 30 seconds, but that’s a long time on air. I could tell John was a little nervous about it too. That’s what I really remember – the terror of that pedal breaking.” (1)

Listen to the recording of that broadcast now and you can hear the moment in Ready or Not, Bob’s opening number, when the pedal strap breaks and he’s forced to start kicking the drum instead. As soon as the song’s over, he drops to the floor to set about emergency repairs. “Keep talking, Bob,” Peel anxiously interjects from his booth. “If you stop, an emergency tape kicks in.” Bob replies from off-mic as he tightens a replacement screw: “It’s not Oasis, is it?” Then he’s off again, blasting into Jump Jump and the rest of his 40-minute set.

The show went out on April 14, 2004, cementing Peel’s conviction that this one-man-band from the Motor City was something special. “This has been fantastic,” he cries as the Maida Vale audience whoop and holler their own appreciation of the set. “Jawbone, Bob Zabor from Detroit – almost a definition of what I would like this programme to be about. This has been magnificent.” Peel’s son Thomas later confirmed his dad had gone “almost mad with excitement” on first hearing Jawbone’s Dang Blues debut album a couple of months before the session itself. The show’s listeners were just as keen, voting two tracks from the album into the top half of that year’s Festive Fifty. (2, 3)

The BBC broadcast turned out to be a life-changing event for Bob. “That’s my big story,” he says today. “I had a John Peel session. Everything else has followed from that.” What no-one knew at the time was that Peel himself would die just six months after the Jawbone session went out – the victim of an October 2004 heart attack while visiting Peru.

When the session offer came in, Bob was still busy honing Jawbone’s trademark meld of gutbucket blues and garage-band rock in a string of open mic nights and support slots round Detroit. “I could never headline,” he explains. “That was out of the question – I’d never bring a crowd in. But when I got a chance to play, people were interested and they did respond. There were always a few people there who got something out of it.”

Things started to look up in December 2003, when he sent out a couple of dozen CDR copies of what would become Dang Blues to college radio stations and any other broadcaster he thought might give it a chance. One of those copies went to Peel’s show at the BBC in London, and the DJ fell on it with glee. “He’s been playing it like crazy,” Bob told a Metro Times interviewer in March 2004. “He’s played almost every cut on it.” (4)

The session invitation had come about a month before that interview, when Peel’s producer Louise Kattenhorn phoned a stunned Zabor household from London. With her help, Bob managed to arrange a handful of UK gigs to help pay for the trip. “I was able to stay in London for a week, do the session and some other shows, so it paid for itself,” he recalls. “My wife Ann was with me on that trip, and John took us out to dinner. He and his team took us to a Thai restaurant right round the corner from the BBC that they’d go to all the time, so that was nice. He was going to have me up to his house to do another session next time I visited the UK, but then he passed away.” (5)

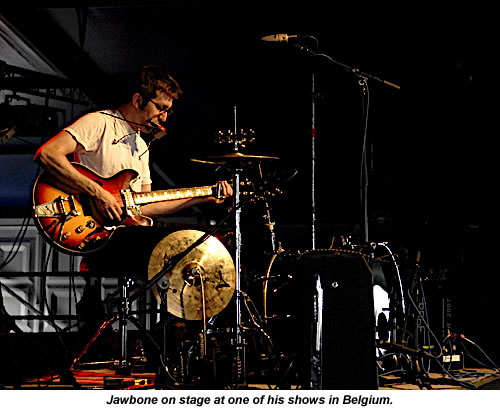

A British label called Loose Music picked up Dang Blues after the Peel session, gave it an official release and ensured it got some publicity. By the end of the year, Jawbone was back here again, this time for a full national tour pulling in his own fans. “They were still small clubs, but now they were full of people who had come to see me and see what I could do,” he says. “That was the difference. I was able to play South by South West [in Austin] and I think that was largely because of Peel. I never toured in the US as Jawbone, though I played a couple of festivals. It was mostly Europe where the interest was – particularly the UK.”

Speaking to an interviewer from National Student magazine, he gave this entertaining description of just what punters could expect at a typical Jawbone show:

“I stand up and sing a song using a harmonica and a drum. I sit down and play some guitar songs. Scream a bit. Howl some. Stomp them drums. Sweat. Break a guitar string. Try to tell a joke while I’m fixing it. Start playing again. Stand up. Scream some more. Catch my breath. Try to retune my guitar. Fail. More harmonica. More howling.” (6)

Jawbone was back in the UK again in 2005, when his gigs included an appearance alongside New Order and The Fall at the Queen Elizabeth Hall’s all-star Peel tribute night. “I have no idea why I did this, but I opened with a spoken word piece,” he recalls. ”I stood in front of my rig with a microphone and a floor tom and would rhyme a few lines and then bang the drum for emphasis. My version of performance art. It was just for a minute or so - some lyrics from a song I never released about the almighty power of music. It went over well enough, but it remains to this day one of those ‘What the fuck was I thinking?!’ memories.”

A second album, called Hauling, followed in 2006, along with another string of UK gigs and slots on tribute albums honouring Johnny Cash, Leadbelly and Hank Williams. One or two other Radio 1 DJs championed him briefly during this time, which helped keep ticket sales healthy and allowed Bob to return home after each UK tour with a small profit.

“It was fantastic,” he says. “It was great to see the country. And the people were really nice. I didn’t make a ton of cash, but I could cover all my expenses and come home with some grocery money for a couple of weeks. I even played a wedding over there in an old hotel somewhere near Liverpool. The guy getting married was a big John Peel fan and he really liked Jawbone. He said: ‘I see you’re coming over – would you play my wedding? We’ll put you up, we’ll pay you…’.” Bob agreed and treated the guests to a half hour set of Jawbone’s finest as they partied at the reception.

By this time, Bob had organised a batch of Jawbone T-shirts and other merchandise to sell at his gigs, which generated some handy extra cash but often proved a nightmare to lug around on tour. “I could never get a booking agent to work with me so I had to book all the shows, schedule the trains and find places to stay,” he recalls. “I’d have to arrange with the club or another band to borrow their bass drum and hi-hat. My wife Ann was with me on the first trip and was able to help me cart everything around, but on subsequent visits, I was carrying everything – guitars, T-shirts, CDs – on a couple of handcarts, pushing one and pulling the other, wearing a backpack. It was borderline ridiculous. Escalators were their own form of terror.”

After four or five UK tours like these – each one completed in a flying visit of 10 or 12 days - it became clear that British gig-goers’ initial appetite for Jawbone’s music had faded, as had their fascination with Detroit bands in general. By 2008, only The White Stripes retained any sizable British fanbase, and Bob realised his UK adventures had come to an end. This time, when he returned to Detroit, he decided to stay there. For those of us watching from London, he seemed simply to vanish overnight.

“It was a bunch of things,” he said when I asked what prompted this decision. “John Peel was gone. I don’t think there was as much excitement with the record. There was personal stuff at home. My wife opened a bakery, so we were working a lot at that. And the economy kind of collapsed. Things were changing musically too. The scene here in Detroit dried up. Unless I could get back to Europe, it wasn’t really worth trying to do.”

With two young children in the family, both still under ten, Bob turned his attention away from music and towards the need for a reliable income. “My first kid was born in 1999, and until then I was just painting houses and industrial buildings and things like that,” he says. “ I’d gone to college and got a degree in computer science in the 1980s, and when the internet exploded I started in doing some web development work.” Now he’s using that computer expertise in a full-time job at Chrysler. “I needed something that would give us health insurance,” he explains. “I needed a real job.”

And that, until very recently, looked to be where the Jawbone story would end.

Bob’s adventures as a musician began in the mid-eighties when, fresh out of college, he moved back to Detroit and set about forming a band called The Gear, with himself on guitar and vocals. “We were influenced by a lot of sixties stuff and British bands like the Buzzcocks, The Jam and the The Clash,” he says. “We lived in a crappy house and we had a van. We were always just trying to get gigs out of town so we could get on the road and have some fun. We played CBGBs a couple of times – but on a Tuesday night, you know? Nobody was there, but for us it was an accomplishment.”

Bob’s adventures as a musician began in the mid-eighties when, fresh out of college, he moved back to Detroit and set about forming a band called The Gear, with himself on guitar and vocals. “We were influenced by a lot of sixties stuff and British bands like the Buzzcocks, The Jam and the The Clash,” he says. “We lived in a crappy house and we had a van. We were always just trying to get gigs out of town so we could get on the road and have some fun. We played CBGBs a couple of times – but on a Tuesday night, you know? Nobody was there, but for us it was an accomplishment.”

The Gear got as a far as putting out a handful of self-published records and tapes and gigged fairly regularly, but never threatened to really take off. “We never went out for more than about five days,” Bob says. “We’d go to Minneapolis of Chicago or something then come home. It was fun, but we never met with any sort of success. None of us was really any good at what we were doing - I was still learning how to write songs and things like that.”

The band lasted about five years, with Bob and one of the other members shifting their attention to busking as its prospects shrank away. They chose a spot in Detroit’s Trappers Alley – then the only place in the city’s devastated centre where any kind of nightlife survived. “There was nowhere to play, so we would just go and do that,” Bob says. Armed with a guitar each and Bob’s harmonica, they belted out a set of covers that wouldn’t seem out of place at a Jawbone gig – or a Gear one either, I dare say. Listing what he can remember of the duo’s busking set today, Bob names The Rolling Stones’ Not Fade Away, Bo Diddley’s You Can’t Judge a Book by the Cover, Chuck Berry’s Memphis Tennessee and Love Potion Number 9 by The Clovers. “We’d bring some wine with us and goof around till somebody snatched our money or the police told us to move along,” he remembers with a grin. (7)

When

The Gear made their split official around 1990, Bob moved to the Detroit suburb of Hamtramck, keeping his hand in with solo open mic nights on the area’s burgeoning coffee house circuit. Once in a while, he’d visit his brother-in-law in New York and do a bit of busking on the subway there. “That was maybe the next five, six years,” he says. “The late nineties was when I starting to do more blues stuff. I had a few songs, so I thought ‘OK, I could do shows with these things. I could open up for somebody, or I could move between bands. I could do something’.”

“It actually started with Dylan,” Bob told me when I asked what influences he’d brought to shaping Jawbone’s sound. “His first couple of records are just guitar and harmonica, and he does some really raw things on there. There was that, and – do you know Bob Log? He was in a band called Doo Rag before going solo – just a two-piece – and that was a really big influence for me. I’d think ‘This is amazing and it’s pretty basic’, so I would give Bob Log a lot of credit for that. There’ve been a lot of one-man bands out there like Dr Isaiah Ross, who lived in Michigan and did some records. I’m still exploring all that – it’s endless.” (8)

“It actually started with Dylan,” Bob told me when I asked what influences he’d brought to shaping Jawbone’s sound. “His first couple of records are just guitar and harmonica, and he does some really raw things on there. There was that, and – do you know Bob Log? He was in a band called Doo Rag before going solo – just a two-piece – and that was a really big influence for me. I’d think ‘This is amazing and it’s pretty basic’, so I would give Bob Log a lot of credit for that. There’ve been a lot of one-man bands out there like Dr Isaiah Ross, who lived in Michigan and did some records. I’m still exploring all that – it’s endless.” (8)

Harmonica and electric guitar were Zabor’s foundations when his started building his one-man band rig. He hooked up his guitar to a 12-volt car battery with some old jump leads to provide power for sidewalk gigs, but quickly realised he was going to need some percussion as well. His first solution was lashing a tambourine to his leg, but that soon gave way to a full-size bass drum he could sit behind and play with its pedal.

“Listening to guys like Bob Log and Dr Isaiah Ross, I realized that if I wanted to play live the bass drum would give me a bigger sound,” he explains. “People seem impressed if you can do more than one thing at a time. If you’ve just got a guitar, they think you’re going to do a James Taylor kind of thing – and there’s nothing wrong with that – but I guess I still wanted to be in a band, so I tried to create one around myself.” (9)

By 2003, he had a full set of his own songs in place for Jawbone and had already put Dang Blues together as a 14-track CDR. “That first record was all live,” he says. “It was done on a cassette four-track. I had a few microphones, so I could adjust the levels like that, but it was all recorded live.” In December that year, he mailed the crucial disc to London. But how, I wanted to know, had a Detroiter like him ever heard of John Peel in the first place, let alone got a sense of the kind of music he played?

The answer turned out to be that any decent Detroit record store at that time was sure to have a John Peel Sessions section in its displays, presumably stocked with the Strange Fruit discs which specialised in putting the best of those sessions out on vinyl. The White Stripes, another back-to-basics Detroit band, had broken big on both sides of the Atlantic in 2001, recording two Peel sessions of their own that year, which may explain why the city’s record stores were so aware of his show. “I heard their session online and thought ‘This guy plays all kinds of stuff, maybe I’ll send him something’,” Bob told me.

Peel was then broadcasting sessions by a lot of other Detroit bands too. By the time Bob contacted him in late 2003, Motor City bar bands like the Soledad Brothers, The Dirtbombs and The Detroit Cobras had all played live on Peel’s show, and all were attracting British fans as a result. There was a buzz in the UK music press that Detroit might turn out to be “the new Seattle”, which focused even more attention on the city. “There was a whole scene going on here,” Bob confirms. “It wasn’t just The White Stripes - they pulled a lot of bands along with them. For me, it was weird timing, because I’d just had my second kid and I was trying to get a real job. I felt ‘Oh my God, there’s all this stuff going on, and I’m just sitting here with the baby’. That’s a lot of what pushed me to get out there.”

For another perspective on Jawbone’s 2004 breakthrough, I tracked down Louise Kattenhorn and Hermeet Chadha, the two producers who then worked on Peel’s show. The first thing I asked them was just how many unsolicited records and CDs the show would receive each day and how they filtered these down to manageable proportions. Just how long were the odds that Jawbone’s disc had to beat simply to get noticed in the first place? (10)

For another perspective on Jawbone’s 2004 breakthrough, I tracked down Louise Kattenhorn and Hermeet Chadha, the two producers who then worked on Peel’s show. The first thing I asked them was just how many unsolicited records and CDs the show would receive each day and how they filtered these down to manageable proportions. Just how long were the odds that Jawbone’s disc had to beat simply to get noticed in the first place? (10)

“I reckon there were two mail sacks worth of records every week, if not more,” Louise replied. “John didn’t like it when Hermeet and I weeded too much stuff out, but we would do a first pass. We’d weed out all the promo CDs that came from major labels – he’d be interested in that music but it wouldn’t be a priority for him. John would gravitate very clearly towards demos and CDRs.”

The next step was to fill two or three cardboard boxes with the most promising submissions and load them into Peel’s car for the trio’s Thursday evening drive from the BBC to Peel Acres in Suffolk, where that night’s show would go out live from his home studio. This drive was their first chance to start listening to the new CDs and discuss their merits. Miraculously, even after 40 years on air, Peel never became cynical or dismissive about this process. “He was very conscientious, and he wanted to listen to everything he was sent, because he valued the relationship between himself and the musicians,” Louise explains. Hermeet agrees: “I remember him saying a couple of times, ‘The next Elvis might be in there”.

And here’s Hermeet again: “As I remember, the Jawbone CD was one of the records John came back with after the Christmas break, one which he was absolutely emphatic we must play – like it was something super-special. I remember Louise mentioned that we had dates at Maida Vale free, and it was really down to her to get Bob to come over. The Maida Vale sessions were a special treat for us, because it was an opportunity to get an audience in. We did one or two a month. I remember John being so into Jawbone that it was almost a given that he’d do a ‘live-live-live’ session on the programme rather than a pre-recorded one.” (11)

Before any of that could happen, there was the question of whether Bob could justify flying all the way across the Atlantic just for one radio appearance. The BBC’s session fee then was just £81.90 for each band member, enough to cover rail fare or petrol money to London in the case of a UK band, but not much help to anyone based in Detroit.

“Sometimes, if the band was broke, we’d let them bring a few of their mates along and include them in the line-up,” says Louise. “We couldn’t do that with Jawbone, because he was a one-man band, of course. I remember him not being sure whether he could afford to come over. It was a pretty big deal for him to do that. I think I reached out to some people and hooked him up with a promoter.”

Looking back now, both Hermeet and Louise see Peel’s love for Jawbone as rooted in his earliest musical passions. “It was a very blues-orientated 1950s record culture that John came from,” says Hermeet. “That was something he knew about: he knew when it was good and he was able to tell people like Louise and I why it was good. Jawbone played an amazing version of that music, and he was so young. It was new music from a new generation, but it sounded like it came from the 1950s.”

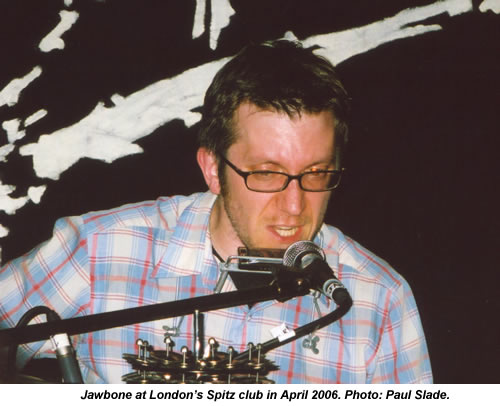

It was the Jawbone T-shirt I bought myself at that Spitz gig which ensured his music never quite slipped my mind. Every time it surfaced in my wardrobe, I’d smile at my memory of the gig and maybe even play a track or two from Dang Blues for old times’ sake. That’s the way things stayed till July 30, 2020, when an unexpected e-mail pinged onto my screen. “Jawbone is alive and well and making music in Detroit,” it declared.

It was the Jawbone T-shirt I bought myself at that Spitz gig which ensured his music never quite slipped my mind. Every time it surfaced in my wardrobe, I’d smile at my memory of the gig and maybe even play a track or two from Dang Blues for old times’ sake. That’s the way things stayed till July 30, 2020, when an unexpected e-mail pinged onto my screen. “Jawbone is alive and well and making music in Detroit,” it declared.

This turned out to be a message from Bob himself, sent to all of us whose names still appeared on his old Jawbone mailing list. “I’ve been working on more music lately [and] I’ve already got a couple of new songs out,” he continued. Links to all the usual streaming platforms followed, where the two new tracks – Jawbone Blues and Medicine in the Water - were already on offer. Since then, he’s averaged another new track every six weeks or so, adding up to a total of 13 new songs by Christmas 2021. I’ve been buying them all, with Chinese UFO, Barn Don’t Burn and Rubberleg among those I like the most. (12)

Despite his decade-plus break from touring and recording, Bob never neglected his music entirely. He was writing songs all that time, and used the break to teach himself piano too. Most important of all was a construction project he embarked on in 2019. “I was able to build a little studio off the back of our garage and that made all the difference for me,” he says. “Now if I’ve got a couple of hours, I’ll just go out to the studio and mess around for a while. Building that was a big part of it for me – just having a place where I could go and work.” He still makes every element of Jawbone’s music himself, but now incorporates occasional drum loops and a spot of multi-tracking when needed.

He sells the new tracks on Bandcamp at $1 a pop, and streams them via Spotify and Apple Music too. Without an outside record label getting involved, new Jawbone discs aren’t a practical proposition right now, and he’s got no immediate hunger to return to live shows either. “I’m happy just recording, practicing and playing,” he says. “If I was to play live, I’d probably just go busking outside a Tigers game or something like that. See where it goes.”

With a big backlog of songs still to work through from his recent hiatus, there seems no danger Jawbone’s well will run dry again. “I’ve usually got four or five songs in the process of recording and thinking about and re-doing, and I’ve got at least that many right now,” he says. Old songs or new, the end result is still unmistakably Jawbone, complete with all the ramshackle thunder that grabbed John Peel’s attention back in 2004. “I always try to make it sound as good as I can, and it always comes out like this,” he told me as we wrapped up our conversation. “If that’s my brand, I’m fine with it.”

Jawbone’s music is available here: Bandcamp / Spotify / Apple Music. All the photos in this article except the Spitz and Zoom ones were supplied by him and used by permission.

Sources & footnotes

1) Unless otherwise attributed, all the Zabor/Jawbone quotes here come from my Zoom conversation with him in December 2021.

2) Peel’s son Thomas Ravenscroft is now a BBC DJ in his own right. His quote’s taken from an article in The Times on December 16, 2005.

3) Jawbone’s 2004 Peel session can still be heard on YouTube. Here’s the link.

4) Metro Times, March 3, 2004. Peel played a track from Dang Blues in all but one of his nine shows between January 27 and February 12 that year. The remaining show, February 3’s, had a Jack White session, so perhaps Peel thought that was enough Detroit for one night.

5) The invitation to do a Peel Acres session was a honour in itself. Peel not only had to really love the performer’s music, but to feel he had a personal rapport with them too. He was inviting them to his family’s home, after all.

6) National Student, September 9, 2008. Judging by the Jawbone gig I saw at London’s Spitz club in April 2006, I’d say it’s a remarkably accurate description!

7) I visited Trappers Alley myself to see some Detroit bands in 2002. Scroll down here to read more about my trip.

8) YouTube has clips of both Bob Log III and Dr Isaiah Ross in action. Bob cited the Delta harmonica player Frank Frost as another key influence when we spoke.

9) Bob’s comments here made me think of something Billy Bragg said early in his own career. Then performing with just his own voice and amplified guitar, Bragg announced his aim was to be “a one-man Clash”.

10) I spoke to Louise and Hermeet via Zoom on December 22, 2021. All their quotes are taken from that conversation.

11) The Maida Vale studio had an open floor for the bands to perform on with Peel’s DJ booth facing them from behind glass. Fans watched the band from the edges of the ground floor or a small balcony above. As soon as the audience was in place, Hermeet or Louise would appear with a couple of carrier bags full of free lager and supermarket wine to encourage a party atmosphere.

12) See above for my links to all Jawbone’s platforms.