Back in 2015, I posted the first Moshpit Memories collection here, pulling together a bunch of anecdotes from my gig-going and other minor adventures between 1975 and 1981. These were drawn from the diary I kept at the time, and started life as a series of daily tweets. Rather to my surprise, the collected version became one of PlanetSlade's most enduringly popular features. People seem to like this stuff, so I thought I'd better provide some more of it.

Back in 2015, I posted the first Moshpit Memories collection here, pulling together a bunch of anecdotes from my gig-going and other minor adventures between 1975 and 1981. These were drawn from the diary I kept at the time, and started life as a series of daily tweets. Rather to my surprise, the collected version became one of PlanetSlade's most enduringly popular features. People seem to like this stuff, so I thought I'd better provide some more of it.

This time, I'm covering the period from 1982 to 2002, when my main obsessions included Alan Moore, The Pogues, The Jim Rose Circus Sideshow and any twanged-up country band still playing America's bar-room circuit. Along the way, I had glancing encounters with various semi-famous folk, and almost always managed to make a twit of myself in one way or another before the conversation was done.

I'd packed up keeping a full-time diary by the time this era began, but would still write up the odd excursion that seemed worth recording, sometimes just as a set of scrawled notes and sometimes as finished prose. As with the first Moshpit Memories, I've polished up these original accounts to make them a bit more readable here and occasionally added some new stuff to give some context. Thanks to the fact that I never throw anything away, I've been able to find plenty of old photographs, ticket stubs and so on to use as illustrations too.

I managed to get quite close to the stage for this gig - down among the groundlings, about 20 feet back, I'd guess. This placed me on Keith Richards' side of the stage, and I remember thinking how remarkably healthy he looked. "This is a man 15 years my senior," I mused. "If half of what I read is true, he has ingested enough hard drugs to fell an army and yet he looks fitter - and just plain better - than I have ever looked in my life. Bastard!"

Aside from that, and the fact that the set opened with Under My Thumb, I have no recollection of the show whatsoever. The YouTube footage confirms it wasn't much to get excited about, though: somewhere in the six years since I'd seen them at Knebworth, the Stones had discarded whatever embers remained of their evil fire and settled for backing Mick Jagger's live aerobics routine instead.

Far more satisfactory was the Ian Stewart Band concert I saw at London's tiny 100 Club on September 16, 1983. Stewart was the Stones' original pianist, of course, and a founder member of the band, but had been sacked by manager Andrew Loog Oldham because he didn't look the part. "Stew, with his short hair, beefy arms and pugnaciously sensible face looked 'too normal' for what Oldham's mental movie camera was already starting to run," Philip Norman explains in his Stones biography. "Oldham's request was that he stay on as their roadie, driver and occasional session pianist. Stew agreed, though his pride was badly hurt." (1)

Stewart had continued working with the band ever since, both live and in the studio. By all accounts, he was the one man in the room the other Stones really worried about impressing, and the only one capable of cowing them into professionalism when they misbehaved. A guilty conscience is a powerful thing.

The 100 Club gig convened a version of Rocket 88, the piano-led blues and boogie-woogie band Stewart formed with Charlie Watts in the early 1970s to keep the two men amused when the Stones weren't on the road. People like Alexis Korner and Jack Bruce would often play with Rocket 88 as well. Rather than the Wolf/Reed/Waters records which inspired the Stones, they took their inspiration from Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson and Big Joe Turner. The result was what Stewart himself called "a band with the best horn players in Europe, a very powerful rhythym section, and the only boogie-woogie piano team in the world". (2)

Rocket 88 always had a rotating cast, and I can't remember who else was in the line-up on this particular night besides Stewart and Watts themselves. They were bloody good, though. You can guage the mood of the evening from the fact that, come interval time, Watts simply bundled up to the bar with all we punters and ordered his drink for himself. Brushed against my right arm while doing so, as a matter of fact - oh, yes.

A relaxed and intimate gig like this, with no celebrity bullshit and none of the faffing about involved in a stadium show is where the real fun's to be had in my book. You can keep your sense of occasion and your big events - just give me a sweaty little cellar and a handful of bluesmen who really know their trade.

1) "It wasn't done very nicely," Stewart tells Norman of his 1963 sacking. "I just turned up one day to find the others had stage suits and there was no stage suit for me. [.] I thought, 'I can't go back to ICI after this. I might as well stay with them and see the world." Norman's book is called The Stones, and was published by Elm Tree Books in 1984.

2) I've taken that quote from the sleeve notes of Rocket 88's eponymous live album, recorded at Hanover's Rotation Club in 1979. Do yourself a favour and check it out.

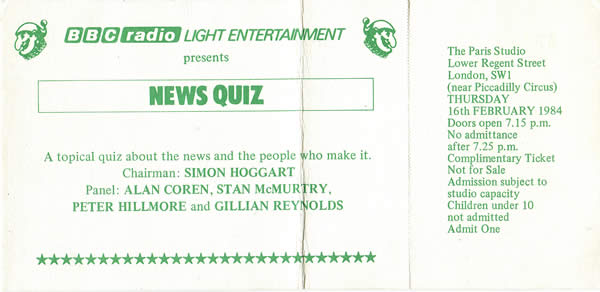

Ah, the great Alan Coren. His columns in (first) Punch and (later) The Times made him the only humour writer I'd even consider mentioning in the same breath as PG Wodehouse. He was always one of the most reliably funny panelists on the News Quiz as well, which is why I applied to the BBC for a free ticket to one of the show’s recordings in central London. (1)

One of the questions that came up that week concerned a team of four housewives who'd just been jailed for smuggling Kruggerands from Jersey to London by hiding them in their knickers. Coren didn't hesitate for a second when this answer was explained: "Talk about penny in the slot," he said.

This remark got a huge laugh in the room, but did not make the show's broadcast edit - presumably because Auntie Beeb thought it was far too filthy.

1) These days, I'd maybe include David Sedaris on my very short list of Wodehouse's peers too. In 1984, though, Coren stood alone.

In the Spring of 1984, I saw a newspaper report that some of the world's best poker players would soon be coming to the Isle of Man for a Texas Hold 'Em tournament organised by Dublin's Eccentrics' Club. I don't play poker, but it all sounded very intriguing, so I booked a week off work and jumped on the Douglas ferry from Liverpool to see what went on at these things.

* The Palace Casino's tournament room is furnished with eight poker tables, plus a sign-in desk and a safe at one end. Each table is presided over by an impeccably-clad dealer. The players are far more casually dressed, however - baseball caps, T-shirts and shorts. The only sign of gambler chic is the odd Binion's tour jacket or a piece of blingy male jewellery.

* The event's first five days, are filled with preliminary games requiring a buy-in stake of anywhere from £200 to £1,000. These are reasonably well-attended, but the real action is in the informal side games, where far more money changes hands.

* Ready money is the only currency poker players appreciate, and such is the demand for it here that the bank next to the Palace runs out of cash on day two. Rather than waiting for cash to be brought in from elsewhere on the island, some players simply fly to the mainland to replenish their bankrolls there.

* Day Six - the big one - is devoted to the Hold 'Em tournament I've come to see. Thirty-four players buy in to the final day's play, each paying a stake of £2,000 to do so, plus a further £200 to pay for dealers and table space. That creates a total pot of £68,000 to be shared among the last five players to survive. The winner will get half, the runner-up 20% and so on. Fifth pace nets you 5%, or £3,400. (1)

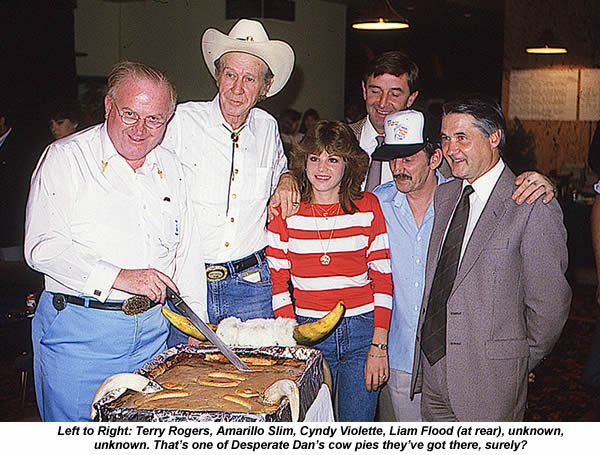

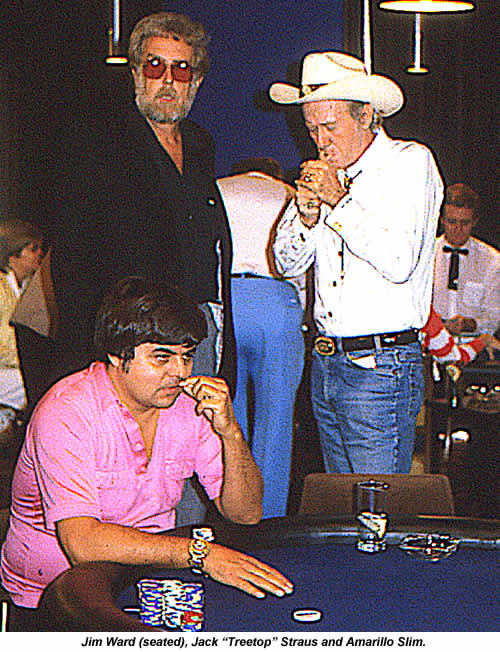

* One of the big name players here is Amarillo Slim, who makes a point of riding to the casino from Douglas Airport on a horse so that all the attending press can photograph him and his surgically-attached Stetson.

* Slim has a colourful turn of phrase. "Good player?" he scoffs at the bar when asked about one of his rivals. "That boy a good player? He couldn't track an elephant through four feet of snow!" When someone else asks him if he's rich, he replies that he's "got enough money to burn up 40 wet mules".

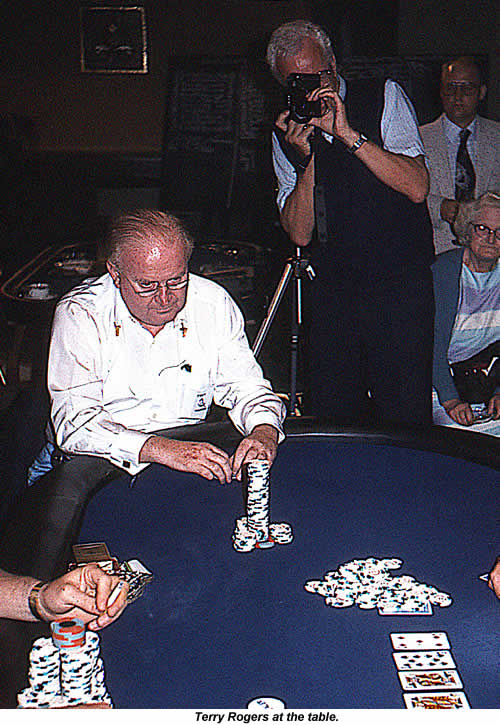

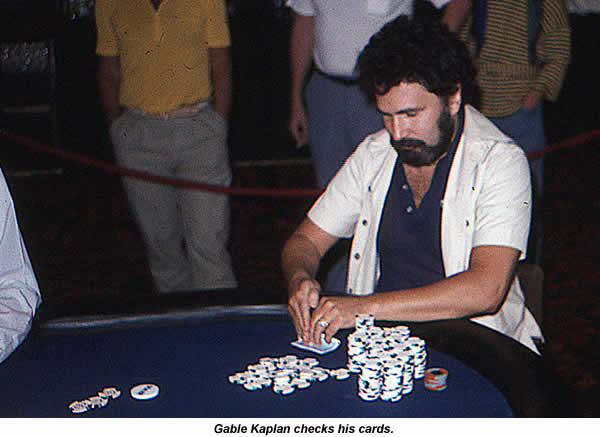

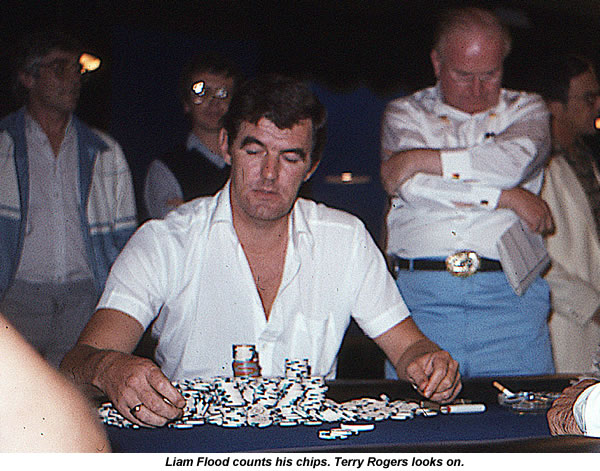

* Other players on the final day include Terry Rogers (the tournament's organiser), Liam Flood (an Irish bookmaker), Cyndy Violette (the only woman taking part), Jack Keller (then the World Series of Poker's champion), Donnacha O'Dea (once an Olympic swimmer), Artie Cobb (who'd won his first WSOP bracelet the previous year), Bill Fain (a physics professor), Gabe Kaplan (who appeared in Welcome Back Kotter), Jack "Treetop" Straus (WSOP's 1982 winner) and Suitcase Johnny (whose real name I never did discover). Rogers, Flood, O'Dea and Johnny are all Irish, the rest American.

* Wandering between tables, I overhear Bill Fain chatting to one of the other players. "I don't believe in all this probability shit," he confides. "I studied physics, so I know that's crap!"

* After 90 minutes play on the final day, just 21 of the original 34 players are left in it. An hour later, Amarillo Slim runs smack into four tens and becomes the first name player to go out. "Ah well," someone nearby tells him. "At least you were beaten in style. Slim grins, agreeing: that's something.

* The remaining 18 players are now grouped around just two tables. Suitcase Johnny is next to fall, followed by Cyndy Violette. A little later, Terry Rogers jumps to his feet after cleaning out Bill Fain to win a place in the last ten. "Ah Terry, Terry, Terry," he declares. "You did it, m'boy, you did it!"

* A buzz goes round the room that Jack Keller is all-in against Liam Flood, so we all gather round the world champion's table to see if he'll survive. He doesn't. Flood takes the hand and Keller is out of the tournament. Just eight players left now.

* As the survivors arrange themselves round the final table, Kaplan welcomes his fellow Americans to what he calls "the legion of doom". The bookies make him a 2-1 favourite to win this thing, with Flood at 7-2 and Rogers at 4-1. O'Dea's the longshot at 18-1.

* The afternoon break is called and Rogers produces a calculator to tot up everyone's current stash of chips and chalk them up on the tournament board. Flood leads with £17,700, followed by Kaplan with £17,150. Rogers himself has £14,850 and Treetop £6,700. Four other players survive, each holding some share of the £11,600 remaining. It's Tom McEvoy's £1,625 which brings up the rear.

* Satisfied he's got his figures right, Rogers ducks over to the edge of the room and - not for the first time, digs a mysterious jar out from under the table. "It's honey," he tells me when I ask. "I don't get much sleep and I need the hit."

* McEvoy's the last player to come down after the break and play resumes about 5:00pm.

* There's a cheer as Flood wins a hand against Treetop. "All this partisanship is terrible," Kaplan jokingly complains. "The Irish cheering every time their man takes a hand. It's like the LA Olympics or something!" He gets his revenge later, as Rogers and Flood face off against each other. "Ah, but I love to see the Irish boys fight among themselves," Kaplan purrs, settling back in his chair to watch.

* Dreams die think and fast over the next hour, and by 6:30pm there's just Rogers, Flood and Kaplan left. Flood now holds £32,400, Kaplan £20,800 and Rogers £14,800. Time for another break.

* Out in the bar, word from the side games is that some guy from Baton Rouge is currently losing between £50,000 and £60,000. Someone else is £30,000 down. My informant's a Scottish lad who'd managed to scare up enough cash to come over to Douglas and play in a couple of the earlier games. His stake soon disappeared, but he seems happy enough with the experience gained. "I know I've got a lot to learn," he tells me. "But now that I've found out where they have tournaments in this country, I'm hoping to play a lot more."

* Play starts up again at 8:00pm. A few minutes later, Rogers goes all-in against Kaplan with a bet of £10,400. Kaplan calmly counts out double the chips and calls. Rogers has two kings and Kaplan two eights, but it all depends on the last communal card - known as "the river". That card is turned, and it gives Kaplan a straight to go with his pair. Rogers is out. "You played great, Terry," one of the spectators consoles him. "You'll never be 4-1 again."

* Half an hour later, it's all over. Flood's modest pair of Jacks is enough to see off Kaplan in what turns out to be final hand and suddenly the Eccentric's have a new champion. "What about a drink then, lads?" Flood declares as he gets to his feet. "I could sure do with one."

* Disappearing to the bar, Flood returns with a drink in his hand. I catch him for a moment to ask how long he's been playing serious poker. "I don't play serious poker," he corrects me. "Tournament play isn't really serious - the outlay's too small." And what are you going to spend the £34,000 on, Liam? "Ah, who knows? I'll probably pay off some of my debts first." (2)

Many thanks to all at The Hendon Mob's poker website for helping me confirm the names of the players in my photos above.

1) In Texas Hold 'Em, each player antes up and is dealt two cards face-down. They examine these cards, and there follows a round of betting. Three communal cards (the flop) are then dealt face-up in the centre of the table, and there's a second round of betting from the remaining players. A fourth communal card (the turn) is then revealed, followed by another round of betting, and finally a fifth communal card called the river. The winner is whichever surviving player can make the best five-card poker hand from his or her own two cards plus the five communal ones.

In tournament play, once you've lost your original buy-in stake, that's it. You're out of the contest, and all you can do is slink off to join a side-game - where the real money changes hands.

2) Des Wilson's 2006 book Swimming With the Devilfish reveals that Flood had been able to muster only 10% of the buy-in money when this tournament began, the remaining 90% being supplied by Rogers and some other friends. That meant they were entitled to 90% of Flood's prize money when he won, of course, so presumably those were the debts he had in mind when we spoke. No wonder Rogers is keeping such a close eye on Flood's chips in that last photo!

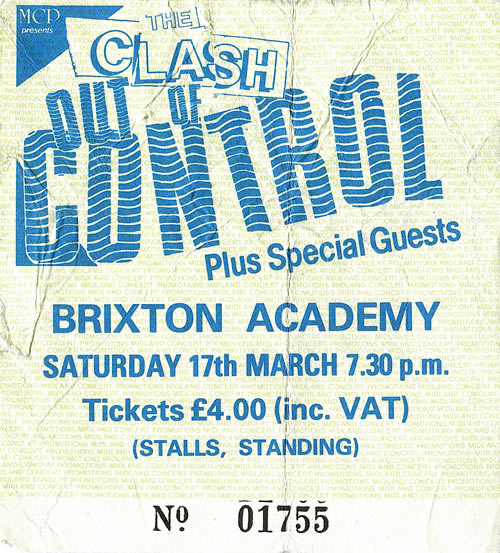

I finally jumped ship as a Clash fan in March 1984, after seeing a truly dreadful gig by the band at Brixton Academy. By that time Combat Rock, their fifth (and very dull) album, had gone top 5 in the US, completing the process of Americanisation they'd begun with London Calling. Only Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon remained from the classic line-up.

On St Patrick's night, I dutifully made my way south of the river to see if they'd managed to salvage anything from the wreckage. It was a dispiriting experience. Strummer did his best, patrolling the edge of the stage with a cut-off mikestand balanced on his shoulder and crouching down to bark impassioned advice at youngsters in the front row. A 31-year-old man with a mohican is always going to look ridiculous though, and it was clear after two or three numbers that he was flogging a dead horse.

I wasn't the only one who thought so. Reviewing the gig in March 24's NME, Gavin Martin called Strummer "an old punk Confucius interspersing the songs with harangues and stream of consciousness raps". Turning to the band as a whole, he said "mostly they were terrible". (1)

Lousy as The Clash were that night, what really irritates me about the gig now is that I missed the support band. They were still about six months away from releasing their first album and their name was Pogue Mahone. The Clash may have lost their place in my heart but - unbeknownst to me at the time - their replacements had already arrived.

1) It was around this time that I wrote a bitter little think-piece about The Clash and submitted it to the NME. I've long since lost the copy, but I can still remember how I ended it: "It took The Rolling Stones 15 years to become completely hopeless but The Clash have managed in it just six. Things happen faster these days."

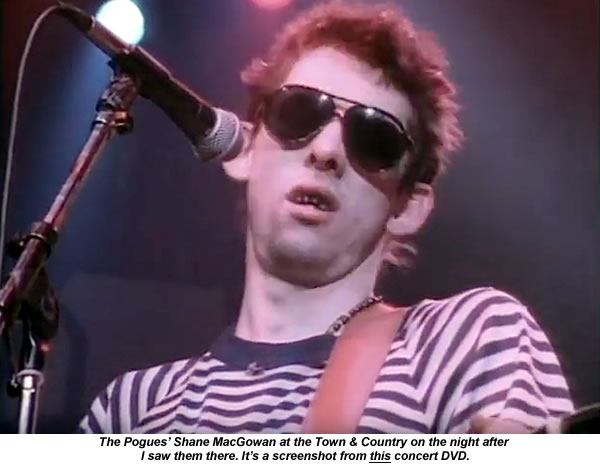

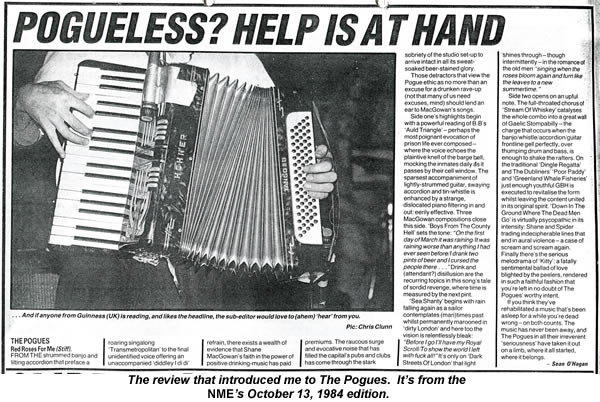

I was still a faithful NME reader at this point and trusted the paper's critics enough to often buy LPs on their recommendations alone. A case in point is Sean O'Hagan's glowing verdict on Red Roses for Me, The Pogues' debut album.

I don't think I'd ever heard the band when I first read this review, but O'Hagan's enthusiasm was enough to convince me it was a must-have. "Shane MacGowan's faith in the power of positive drinking music has paid premiums," he wrote. "The raucous surge and evocative noise that has filled the capital's pubs and clubs has come through the stark sobriety of the studio set-up to arrive intact in all its sweat-soaked, beer-stained glory." That was good enough for me, so I went out and bought the album next day.

It was love at first listen and I immediately started telling all my friends what a great album this was. I took to reminding people that I was half Irish - something I'd never given much thought to before - and adopting a cod Irish accent when singing along to MacGowan's gutter anthems. I went on about the band so much that their name started to register even with people who had no interest in their music. When I changed jobs for a move to London in August 1985, one of the art department guys I'd worked with made me a leaving card drawn up to look like a comic book cover. The lettering he included announced that the story inside was called "The Curse of The Pogues". (1)

One of the reasons I loved this band so much was MacGowan's remarkable songwriting. His best songs dragged the folk tradition's tales of underclass life out of the history books and into the Camden and Soho streets which he and the band's fans walked every day. He filled his songs with everyday details of London low life - rent boys, tramps, pubs and dog tracks - but was never patronising. Like Tom Waits in his early career, MacGowan often chronicled the drinking life and did so with an authenticity and affection which made it clear he was no mere tourist. (2)

Many of his songs were already feeding back into the Irish pub song repertoire which helped inspire them, promising a kind of immortality mere pop stars could only dream of. His epic boozing was already making it look like MacGowan himself wouldn't be with us for long, but you could be damn sure his songs would survive.

When I moved to London in 1985, I rented a room in Stoke Newington and worked in Soho. This put me smack in the middle of Pogues territory and I started to identify with the band's records even more closely as a result. Every night after work, a crowd of us would pile into the Star & Garter in Poland Street for a nice boozy evening. Posters carrying MacGowan's face were plastered all over Soho by this point - part of a Stiff campaign promoting one of the band's early singles - and I'd always point these out as we headed home at the end of the night, imploring my companions to "give this man a hit before he kills himself". It seemed a ridiculous thing to hope for at the time.

1) The card was based on one of Howard Chaykin's American Flagg covers. Flagg was one of my favourite comics at the time, and I tended to drone on about it almost as much as I did The Pogues.

2) Although his songs always have a sentimental side, MacGowan tempers his romanticism with a stubborn realism Waits lacks. The vagrants who Waits sings about in On The Nickel are portrayed as overgrown children, with all the innocence that implies. Although they are forced to sleep rough, no real harm ever seems to come to them. MacGowan's equivalents in The Old Main Drag are close to death and no longer able to control their bodily functions. They are prone to sudden incoherent yells and always at risk of a random beating. I love Waits' boozy songs too, but this distinction between his approach to the subject and MacGowan's is one worth making, I think.

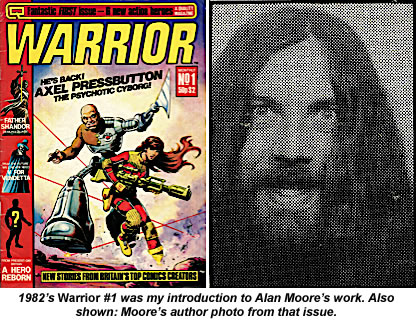

I discovered Alan Moore's work in early 1982, when I stumbled across the first issue of a British comic called Warrior, where both his Miracleman (then Marvelman) and V for Vendetta strips first saw print. Two years later, in January 1984, he started writing Swamp Thing, his first US comic, by which time I'd also been able to catch up on all the earlier 2000AD work of his which I'd missed first time round. I've been a fan ever since.

In September 1985 I went with a friend to Britain's first major comics convention. Known as the UK Comics Art Convention (UKCAC for short), this event had booked an impressive array of comics talent to appear on its panels - including Moore himself.

We got our first glimpse of the great man during the opening day's "Meet the Guests" session, when each writer or artist attending was brought on stage for brief introduction and a run-through of the convention events they'd be doing.

When Moore's name was called, a tall, broad-shouldered figure with long, dark hair, a full beard and hooded red eyes appeared from the wings. He was wearing a glittery blue "Mr Showbiz" suit and matching brothel creepers. None of us in the audience had much idea about Moore's appearance in those dark pre-internet days. Now the mystery was solved: he looked like Charles Manson wearing Ben Elton's stage gear.

Moore's comments from the stage, both in this session and his subsequent panels, made it clear he was far more articulate and much wittier than any of the other guests. I got the impression he was still slightly surprised to find himself so feted in America and very much enjoying the chance to meet the older creators there who'd produced all the comics he loved as a boy. He playfully acknowledged this by dropping in references to Dick Giordano (". or Dick as I call him"), Jack Kirby (". or Jack as I call him") and New York (". or New as I call it") whenever he got the chance.

When Moore made himself available for a signing later in the day, I got him to autograph a few issues of Swamp Thing, told him how much I liked his work, and left it at that. Watchmen was still a year away, but the queue at his signing table was already a long one. Everywhere he went at the convention, he was besieged by adoring fans and not allowed to move on till he'd signed everything they pushed at him and answered all their questions. I would have loved to talk to him properly, but in those circumstances it was never going to be possible.

I've always had a problem knowing what to say to people whose work I admire, as simply throwing compliments at them always makes me feel like a fawning inadequate. There's seldom time for anything resembling a normal conversation, so the preliminaries we usually rely on to break the ice must be severely truncated or omitted altogether. Next time I saw Moore at a convention, I decided, I would attempt to cut to the chase with a single, memorable remark which made clear both my own deep knowledge of his work and the fact that I was no ordinary fan. What could possibly go wrong?

I next saw Moore at the Birmingham Comic Art Show - that's Birmingham in the British Midlands, not the one in Alabama. This time, he showed up in a silver suit.

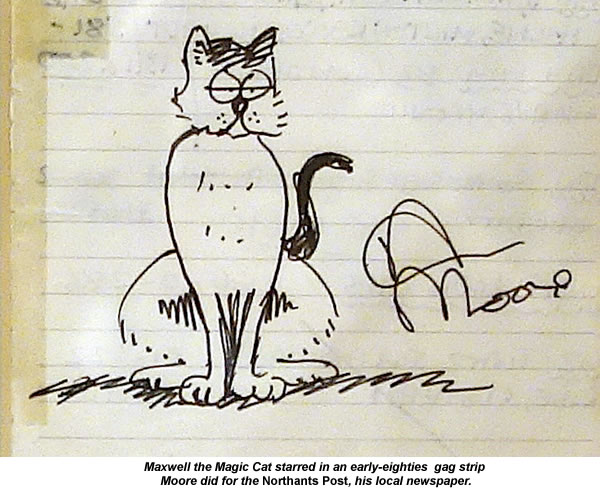

I'd read an interview in some fanzine or other where Moore had noted ruefully that comics were always likely to draw attention more for their art than for the quality of their writing. Fans always wanted artists to draw them a sketch, he jokingly complained, but no-one ever asked their favourite writer to pen them a paragraph. I filed this remark away with my growing stock of Moore trivia and remembered it again at the Birmingham show. Seeing him momentarily alone in the dealers' room, I went over, handed him my pocket diary open at a conveniently empty page and asked him to write me a sentence.

He looked at me askance and replied, "I'll draw you a picture of Maxwell the Magic Cat instead". As he did so, I babbled an explanation of how my mind had been working and he grinned vaguely at what a twerp I was. He handed my diary back with the completed drawing above then made his excuses and left. It had not been the ground-breaking encounter I'd hoped for, but at least I hadn't completely embarrassed myself. If only I'd had the sense to leave it there.

The first time I saw The Pogues live came just a few weeks after they'd narrowly missed nabbing a Christmas number one with Fairytale of New York. They'd had

to settle for the number two spot instead, behind the Pet Shop Boys' Always On My Mind, but it remained a remarkable achievement. (1)

On the strength of The Pogues' unexpected chart success, I managed to talk a bunch of work friends into coming with me to one of their gigs. The band were playing seven consecutive nights in London, the first six at North London's Town & Country club and the seventh at Brixton Academy. We chose the Wednesday night because that was furthest away from our weekly press day, and I was sent off to buy us half a dozen tickets.

One of the workmates I'd persuaded to come along was a rather Sloaney young woman whose normal idea of a raucous night out was yakking in the wine bar with her mates. Let's call her Hannah. I knew the whole of the Town & Country was going to be one huge, drunken moshpit at a Pogues gig - particularly one held in Kentish Town on the night before St Patrick's - and I did try to tell Hannah what she was letting herself in for. She kept insisting she'd be fine.

The first thing we saw as we entered the Town & Country was a young lad passed out on the floor in a small pool of his own vomit. He still had a plastic pint glass clutched in one hand, but had allowed its contents to pour out and soak into his shirt. Hannah stepped over him gamely and headed for the bar. She probably felt like she needed a drink.(2)

Half an hour later, The Pogues were leading a packed Town & Country club through a massive pissed-up ceilidh. The entire dance floor - an area about the size of two tennis courts - was packed tight with 1,200 drunken Pogues fans, who had no space to do anything by pogo, throw their beer in the air and shout along to MacGowan's matchless lyrics. Kirsty MacColl came out to duet on Fairytale, waltzing with MacGowan through a flurry of artificial snowflakes during the song's instrumental passage, and stuck around for three or four of the subsequent numbers too.

The great man was still clean-shaven at this point, still had most of his teeth, and had yet to begin the long slide downhill which would follow. Even so, you could not deny he was pissed. Every now and again, he'd give a gormless glace across the stage which suggested he'd momentarily lost track of what was going on. No matter. MacGowan's role on these occasions was to be the personification of drunkenness itself and the more wrecked he was, the more we loved him for it. If he really had died in his thirties - which was what everyone then expected to happen - we'd all have carried some of the blame for egging him on.

1) I think it's fair to say The Pogues were somewhere round their peak at the time of these gigs. If I Should Fall From Grace With God, probably their best album, had been out for only a couple of months and MacGowan was still (more or less) fully present on stage. By the time they came to record Peace & Love in February 1989, both his songwriting and his singing had sharply declined. The other members stepped up manfully to fill the gap, but without MacGowan firing on all cylinders they'd never be quite the same band again.

2) Next day at work, Hannah assured me she'd really enjoyed the evening. I think she was just being polite, but who knows?

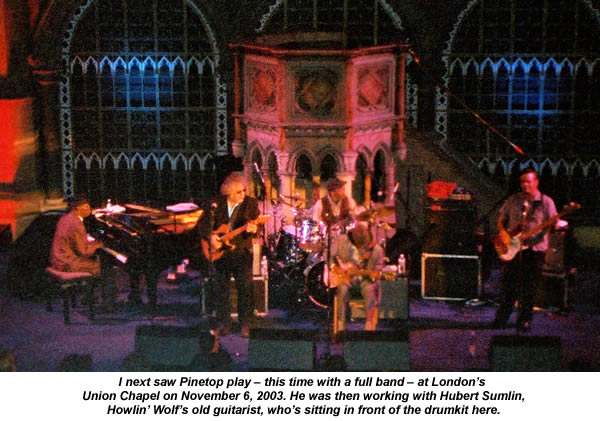

I found a sports bar called Players a couple of blocks west of the Chelsea Hotel (where I was staying) and planted myself there to enjoy a Michelob and read my Village Voice. The Voice had one of New York's best listings sections in those days and I was delighted to find that Pinetop Perkins had a gig lined up at the Lone Star Café in a few days' time.

I knew Perkins' work from his time with Muddy Waters' band, where he played piano from 1970 until Waters' death 13 years later. When Johnny Winter put Waters together with some other expert bluesmen for the magnificent 1977 album Hard Again, Pinetop was right there with him alongside James Cotton, Bob Margolin, Charles Calmese, Willie "Big Eyes" Snith and Winter himself. Muddy and Pinetop were both over 60 when they recorded that album, but they led the band in a performance which many 20-year-olds would envy for its sheer potency. Amazingly, 1978's I'm Ready - a follow-up album which Pinetop also plays on - is just as good.

I loved both those records to bits, and I was still kicking myself for missing the chance to see Waters live when he'd visited London during this late flowering of his career. Still, Pinetop Perkins would be a substantial consolation prize, particularly when he was playing a venue as good as the Lone Star Café. This Fifth Avenue bar, which I'd first visited to see Albert King in 1979, was one of the best places in New York to see rootsy live music. Pinetop was 75 years old by the time I read his name in the Voice that day, but I had no doubt he'd still be capable of tearing the roof off at that particular joint. I took a pen from my pocket and made a big red circle round his name.

The following Monday, I got to the Lone Star about 9:00pm, found a seat near the stage and ordered my first beer of the evening. Most of my fellow drinkers that night were in their 30s or 40s and - as far as I could tell from the conversations I overheard - seemed pretty knowledgeable about the blues heritage Pinetop represented. Here was a man who'd been playing the blues since the era of Robert Johnson and Son House. He'd recorded at Sun Records' Memphis studios a year before Elvis Presley made his first commercial recordings there. The blues legends he'd worked with included not only Muddy Waters, but also Earl Hooker, Sonny Boy Williamson and Junior Wells. (1)

Blues and boogie-woogie make perfect drinking music and always sound better in a bar than they do in any other setting. Seeing Pinetop do his stuff at close quarters in a venue so ideally suited to the purpose was sure to be a treat and everyone gathered at the Lone Star that night knew it. That's just how it turned out too. Pinetop, immaculately attired in his trademark brown suit and fedora, sang and played his way through a loose, rolling set of blues standards like High-Heeled Sneakers, Hoochie-Coochie Man, Chicken Shack, Got My Mojo Working and Kidney Stew. He also gave us several of his own compositions, including Down in Mississippi and the irresistible Big Fat Mama. Bonnie Rait showed up to help with a couple of numbers and everyone had a great time. For pure intimacy and atmosphere, it remains one of the best gigs I've ever seen.

1) Pinetop died in 2011, aged 97. Here's an extract from his New York Times obituary: "His longevity as a performer was remarkable - all the more so considering his fondness for cigarettes and alcohol; by his own account he began smoking at age 9 and didn't quit drinking till he was 82. Few people working in any popular art form have been as prolific in the ninth and tenth decades of their lives."

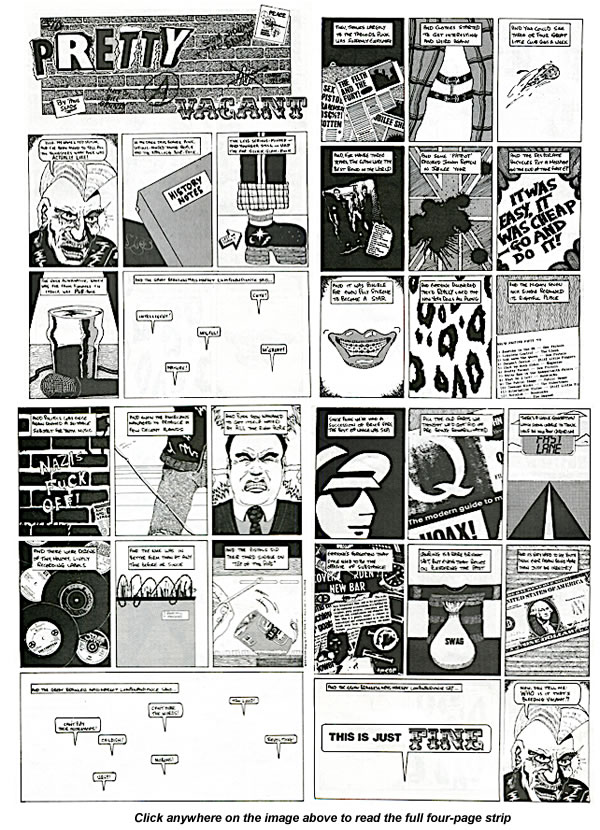

Heartbreak Hotel was a small press magazine I contributed to in the late eighties (and which I've written about here). Each issue was themed round a different style of music, and carried a handful of short comics stories based on famous songs from that particular genre. My turn to do one came with the punk issue, and it was the Pistols' song Pretty Vacant I chose to use. A lot of it got cobbled together over the course of a long Saturday night in June 1988, when reading Clive Barker's Books of Blood had left me too spooked to sleep.

Shortly after the Birmingham show, Moore stopped attending conventions altogether. You couldn't blame him, because his celebrity took a quantum leap with the success of Watchmen and the fan-worship he received at conventions would have become quite unmanageable as a result. Here he is explaining the decision in a 1990 interview with The Comics Journal:

"I used to go to comics marts, small mini-conventions in England, and in the bar comics enthusiasts - who I didn't see as fans at the time - would come up and just talk to me. And I'd enjoy talking to them. I'd have a beer with them and we'd talk on a one-to-one level. It wouldn't have been in terms of me and my adoring audience.

"You can do that when it's only 10 or 15 enthusiasts, but you come to a point where there's 60 or 100 fans [and] you can't have a one-to-one relationship with that many people. Inevitably, you end up addressing them en masse from your podium or whatever.

I'm not interested in those types of relationships with people. They don't feel balanced, they don't feel fair, they don't feel positive. They feel like one or more parties is inevitably going to get degraded in a situation like that, so I try to avoid them."

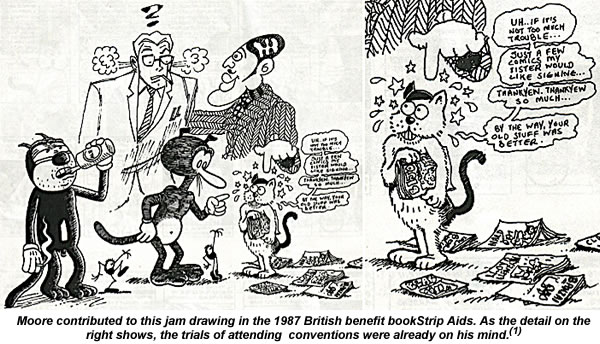

Moore was an occasional contributor to Heartbreak Hotel, the small press mag I mentioned in the previous item, giving it a couple of short comics stories he'd both written and drawn himself. One was about his 1987 trip to New York and the other inspired by the Move's psychedelic 1967 hit I Can Hear The Grass Grow. He'd also given Lionel and Don - the mag's publishers - some stuff for their previous venture, a cartoon anthology called Strip Aids which raised money for London Lighthouse.

All in all, then, it was only natural that, when Heartbreak Hotel threw a party at a London bar called the Conservatory, they invited Moore along. Lionel knew how much I liked Swamp Thing and Watchmen, so he promised to introduce me on the night.

Moore's fame had gone through the roof since Watchmen came out. I still loved the comics he produced, but I could also see that some of the praise given him in the fan press was ridiculously overblown. In the small, self-regarding world of comics, a talent like his shone all the brighter, and this led some reviewers to suggest he was Shakespeare, Milton and Melville rolled into one. My own view was that he was a very good genre writer - even a great one on his day - but that it was people like Clive Barker and William Gibson rather than the giants of world literature who were his true peers. I suspect he'd feel much the same way himself.(2)

This was the cocktail of thoughts swirling through my nervous brain as Lionel steered Moore towards me at the party. Lionel introduced us, Moore said hello and I opened my mouth to see what came out. I should have said I liked his work. I should have said it was nice to meet him. I should have said it was remarkably pleasant weather we were having. Instead, what I said was this:

"Hello. Boy, you really ripped off a lot from Clive Barker, didn't you?"

Moore took this boorish remark as well as anyone could. He blinked a bit, said he didn't think Barker was that much of an influence and asked which particular bits of his work I had in mind. I babbled something about the Winchester House issue of Swamp Thing reminding me strongly of a story in Clive Barker's Books of Blood, and Moore listened politely for a few minutes before Lionel led him off to find someone less oafish he could talk to. My remark was particularly unjust, because Moore had actually given Barker a substantial nod in Swamp Thing by showing one of the book's characters reading precisely the Barker collection I'd mentioned.

Perhaps Moore is right in saying that the worshipper/worshipee relationship implied by fandom dooms all such encounters before they even begin. Two years after the Heartbreak Hotel party, I read the Comics Journal interview quoted above and saw Moore refer to fans who said "ridiculously flattering things about the work which made you feel bad because they weren't deserved, or ridiculously critical things about the work which would make be feel annoyed because they weren't deserved". I cringed all over again after reading that, because I knew I'd avoided the first trap only by stepping squarely into the second. Sorry, Alan.

1) The other contributors to the jam drawing above were: Dan Clowes (Lloyd Llewellyn); Skip Williamson (Snappy Sammy Smoot); Jay Lynch (Pat), Kim Deitch (Waldo) and Larry Marder (beans).

2) This whole period of Moore's career now looks like his juvenalia to me. The real highlights would come much later, including From Hell (comics, 1999), The Highbury Working (audio CD, 2000), Promethea (comics, 2006), Neonomicon (comics, 2011) and Jerusalem (prose novel, 2016). His upcoming movie The Show looks like being something pretty special too.

I next saw The Pogues at Brixton Academy, when The Chieftains joined them on stage half way through the evening. We'd already had ten songs by The Pogues alone at that point, but there were 14 more in store where the two bands would muck in together as a single joint ensemble.

The numbers they chose for this second set were split about equally between The Pogues' own stuff and traditional Irish songs both bands knew. From The Pogues' side of the fence, we got Streams of Whiskey, Repeal of the Licencing Laws, Kitty and London You're a Lady, plus Dirty Old Town and Waxie's Dargle, both of which they'd more or less made their own on the first two albums. They also roped The Chieftains in on a rollicking version of The Irish Rover, which The Pogues and The Dubliners had made a top ten single four years earlier. "And the poor aul' dog was drowned," we all roared along as the song reached its penultimate line.

"The Chieftains had a job holding on to their more subtle bits, but they had a brave try, joining The Pogues in a swampy, joyful mess," the following week's NME reported. That's pretty much how I felt about the night too - though my own clearest memory of it is a visual one. I think it was during Repeal of the Licencing Laws. On one side of the stage, I could see The Chieftain's Derek Bell serenely seated at his beautiful antique harp while, just a few feet away from him, The Pogues' Spider Stacey was hopping about like a lunatic as he frantically tried to shake the spit out of his tin whistle. If you wanted one image to capture the spirit of the whole evening, that'd be the one to choose.

I was living in Finsbury Park by this time, and most weekends I'd trot along to The Osbourne Tavern in Stroud Green Road to have a couple of pints and enjoy the band there. They were an engaging bunch of nutters called Psycho Ceilidh, who played the Osbourne pretty regularly and were always a hell of a lot of fun.

We'll get to them in a minute, but first let me tell you my little story about the Osbourne Tavern itself. I was in there on my own one evening, probably about 8:00pm or so, sat at the bar and minding my own business. There was a small group of guys drinking over to my left, all taking the piss out of one another in what seemed to be a perfectly friendly way. Suddenly, there was a flurry of curses and waving arms from that corner, at which point one of them stormed off shouting in fury. I had no idea what it was all about, but he was clearly very upset - not just angry, but hurt too.

He stopped in the doorway leading out into the street, then turned back to yell at his former companions again. "I've got a fucking GUN in my car!" he shouted. "I'm going to come back in here and shoot every one of you cunts!" He seemed to mean not just the little group of people he'd been talking to, but all the rest of us too.

His companions laughed their heads off at this, telling him to fuck off and stop being such a twat. No-one else in the pub seemed to take him remotely seriously either, least of all the barman, who'd barely glanced up from his copy of The Sun as all this was going on. I turned away from the door again - a little nervously, I admit - finished up my pint as quickly as I could without looking a fool, and then strolled across the road to the White Lion to resume my evening there. There was nothing in that week's Hornsey Gazette about a bloodbath at the Osbourne, so I assume our would-be killer simply went home to sleep it off.

Anyway: back to Psycho Ceilidh. The band's three core members were singer Fiach McHugh (who also played bodhran), guitarist Willie Barr and bassist Steve Daley, who doubled on mandolin. Generally, they'd have a fourth musician with them too, such the fiddler Chris Short or a banjo player called Dick Smith, who went on to join The Coal Porters. They played a set of noisy Irished-up covers with the same attitude of frantic, ramshackle abandon The Pogues had brought to their Kings Cross pub gigs a decade earlier.

Short, now with Churchfitters, played a couple of dozen Psycho Ceilidh gigs at around the time I saw them. "It was very much a live band, very much a pub band," he told me over the phone from France. "I loved playing with them. I had lots of good times. Lots of drinking, lots of having a laugh, but behind it music that had some originality and a lot of kick to it.

"The gigs were all mad, but incredible fun. I remember nearly getting lynched one time in the Osbourne Tavern for our version of Danny Boy. It was a hell-for-leather punk version, with Fiach screaming the lyrics at the top of his voice and the rest of us doing a sort of punk accompaniment behind him. Some of the more traditional drinkers there thought we were taking the piss. It very nearly turned nasty."

One of the things that made Psycho Ceilidh unique was their habit of dragging New York art rock songs like Talking Heads' Psycho Killer into their set and roughing them up a bit. Best of all was the distinctly idiosyncratic rewrite they gave to Lou Reed's Vicious, which usually begins like this:

You're vicious,

You hit me with a flower,

You do it every hour,

Oh baby, you're so vicious!

In Psycho Ceilidh's hands, this became:

You're savage,

You hit me with a cabbage,

Three times a week on average,

Oh baby, you're so savage!

Genius! "As with the Churchfitters, we always wanted to do things in a version you'd never heard before," Short told me. "In the case of Psycho Ceilidh, it was a version you'd never even imagined before!"

There was a stripped-down busking version of the band too, known as Reels on Wheels, which comprised just Daley, Barr and Short. "We would jump into a carriage on the London Underground and Steve would shout, 'Nobody move! This is a polka!'," Short recalls on Churchfitters' website. "Surprisingly, I was arrested only once."

On another occasion, Reels on Wheels had just entered the carriage when the train driver announced he would refuse to move off the platform till these "pickpockets disguised as buskers" got out. "The whole carriage said 'That's not true - you stay right there'," Short told me. "So we just waited till the driver got fed up and moved the train. It was nice to have the support of the people rather than thinking we'd annoyed them, you know?"

If anyone else has memories of Psycho Ceilidh - or, better yet, a photo of them in action - please get in touch. I'd love to pass on any further information here.

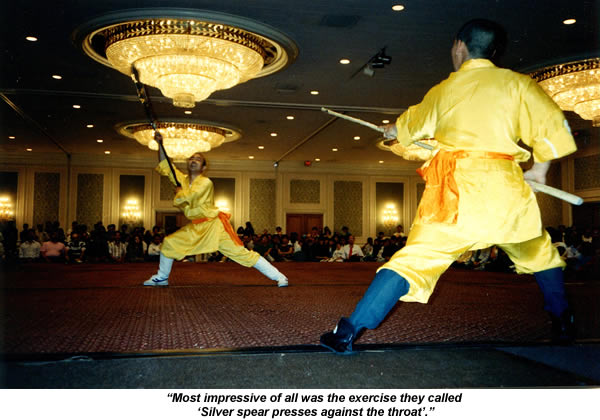

These guys were not to be trifled with, as a note from the evening's programme made clear. This told the story of a young man called Hui Ke, who arrived at Monk Bodhidharma's cave one winter and asked to become the old master's disciple. Bodhidharma replied that he would not take him on till the snow turned red., at which point Hui Ke sliced off one of his own arms, turned the snow red with blood and secured an entry-level position. He went on not just to study with Bodhidharma, but eventually succeeded the old man as abbot of the Shaolin Temple.

Among the audience surrounding a raised platform in the hotel's Plaza ballroom were a group of Chuck Norris types, who I took to be Houston's martial arts elite. Their sense of awed respect throughout the monks' demonstration of their martial arts prowess was palpable. The feats we saw that night had names like "Iron head brick breaking technique", "Golden tongue touches fire" and "Empty hand against sword" - and as far as I could see every one did just what it said it on the tin.

Most impressive of all was the exercise they called "Silver spear presses against the throat". One monk took a six-foot spear, the wooden shaft about as thick as a man's wrist, and slashed a piece of paper with it to show how sharp it was. The paper split as cleanly as if he'd used a razor blade. He then placed the point of the spear against his own throat, just below his Adam's Apple and held up the shaft for a colleague to take. The second monk placed the blunt end of the spear against his own chest and then the two men started slowly walking towards another. The spear's shaft flexed upwards in a parabolic curve as they took each successive step and then, with a loud crack, snapped in two. It was quite a sight. (1)

1) Yeah, yeah: I know. The shaft of the spear probably wasn't anywhere near as strong as it looked and may well have been hollow to boot. Maybe the business end of the spear had sharp edges to allow for the slicing of the paper, but a rounded tip to minimise damage to the performing monk's throat. I'm sure some of these basic magician's tricks figured in the demonstration somewhere, but on the night I chose to put scepticism aside and simply enjoy it.

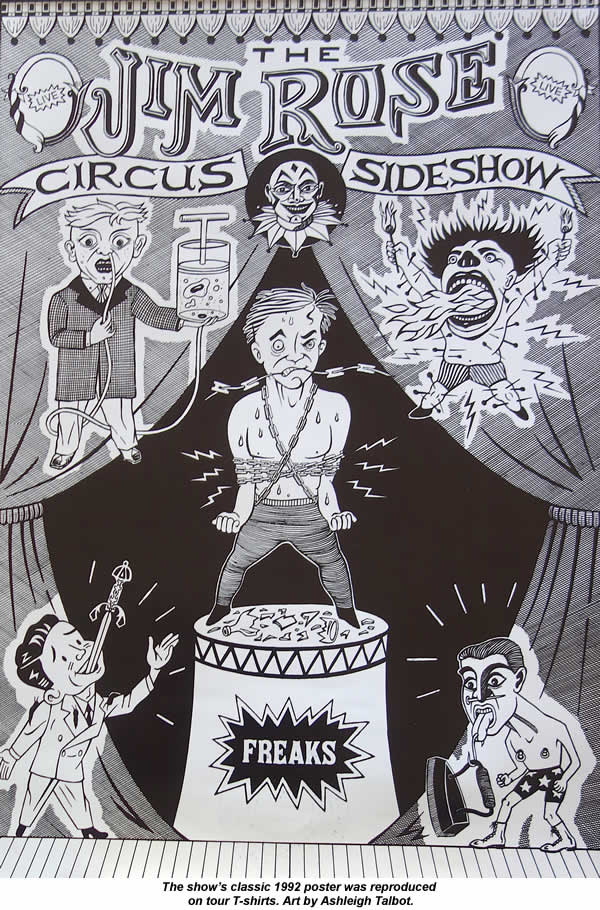

I was half-drunk in a tatty rock club near Washington's red light district. It was approaching midnight, I was miles from my hotel and I had no very firm plan how I was going to get back there after the show. Just yards from where I stood, a man was dangling a concrete block from two chains attached to his pierced nipples, a procedure which threatened - in the words of his friend Jim - to "make Dolly Parton look flat".

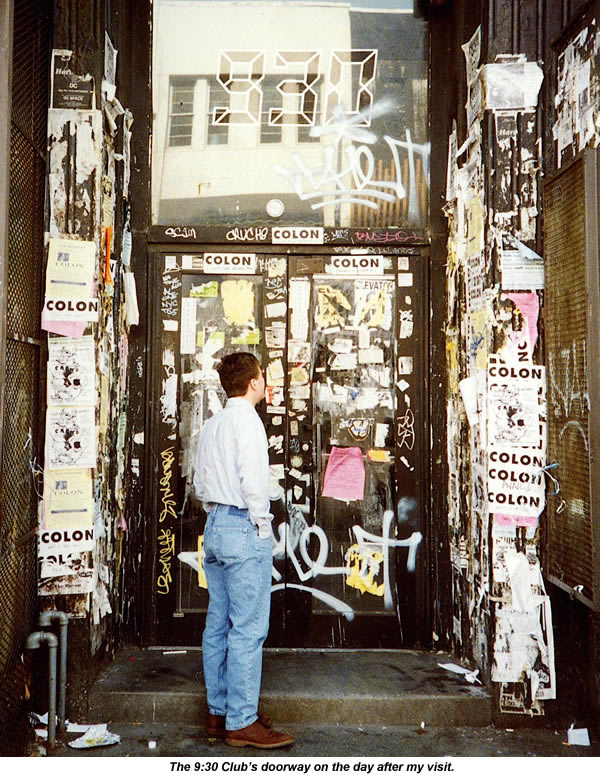

Not everyone's idea of a good time, I know. But I was happy enough. I had come to the 9:30 Club on Washington's F Street to see The Jim Rose Circus Sideshow perform as part of the troupe's 1992 Eyeball Terrorist tour. This was the classic Jim Rose line-up: Rose himself, his wife Bebe, Mr Lifto, The Torture King, The Enigma and Matt "The Tube" Crowley. They'd just got off the 1992 Lollapalooza festival tour, where they'd played to crowds of 7,000 or more all over the US.

I'd set off for F Street far sooner than necessary that night, thinking I'd better leave myself a bit of extra time to find the club. In the event, I needn't have worried because its entrance stood out a mile. The Atlantic Building's once-elegant doorway was plastered with stickers, fliers and spray-paint slogans promoting bands who'd played there or hoped to do so soon. Whichever member of Colon was responsible for placing the band's own stickers had done a particularly thorough job.

Most of the stores and restaurants on this stretch of F Street were semi-derelict and covered in posters of their own. Many bore graffitied tags from the Crips street gang or from someone calling himself "Cool Disco Dan". I retraced my steps to a nearby bar and killed the next hour with a couple of beers there.

Back on F Street, I found the 9:30 packed with typical grunge rockers and college kids. I could see the place was perfect for the sleaziest kind of rock 'n' roll. The barmaids were dressed in cheap knock-offs of Madonna's conical bra, and there were TVs tuned to white noise and static in every corner. The whole place was dark, poorly-decorated and filthy - just what I'd hoped for, in fact.

Nothing was happening on stage yet, so bought a tour T-shirt at the merchandise table and then staked out a spot at the bar which gave me both a clear view of the stage and easy access to more beer. Two Rolling Rocks later, some calliope music kicked in on the PA and we were ready to begin.

Rose's main role was to MC the show, but he also warmed the audience up with a few tricks of his own. He tapped a nail into his nasal cavity with a hammer, allowed Bebe to throw darts into his naked back, rested his face in a bed of broken glass and popped his shoulder to escape from a straightjacket. He also attempted to tumble dry ice on his tongue long enough to produce twin "smoke rings" from his nose and mouth. When this trick failed to come off, everyone applauded anyway. "No, don't," Rose said, spitting out the ice. "I fucked up! I was scared!"

And perhaps he was. Rose's feats were certainly not risk-free. But his own act owed as much to old-fashioned hokum and a knowledge of human anatomy as it did to any fakir-like abilities on his part. The real meat of the show - in more senses than one - came with Mr Lifto and The Torture King.

Lifto's speciality was an unusual weightlifting act, which involved him hefting a suitcase, two domestic steam irons and the aforementioned concrete block from chains attached to his pierced earlobes, tongue, nipples and penis. The most striking part of the act came when he attached the irons to his dick and swung them too and fro between his legs. The supporting organ protested this cavalier treatment by stretching to four times its normal length and threatening to snap in half like an old rubber band.

This is the kind of spectacle that tends to make local councillors a little nervous, and many municipal authorities had ruled that Lifto could perform this part of his act in their town only if his (increasingly) dangly bits were somehow concealed from full view. Sometimes, Lifto dealt with these objections by placing a waist-high gauze screen in front of his soon-to-be-stretched member, producing a bizarre shadowplay.

For the Washington show, he relied on a liberal coating of shaving foam. I have since seen him performing the same feat au naturel, however, so I can vouch for the fact that no prosthetics were involved. Judging by the expression on his contorted face as the irons swung back and forth in Washington, it hurt too.

Next up was The Torture King, who proceeded to push a selection of hatpins and meat skewers through his arms, neck and face. It's the small details of his act which I remember most clearly. I recall, for example, that the flesh on his left forearm extended into a cone shape and resisted for a moment just before the skewer punched through to open air. I also noticed that the long hatpin which he poked through both cheeks picked up a tiny bead of saliva on its tip as it journeyed through his gaping mouth. You could see it there, glinting in the stage lights. (1)

After Mr Lifto and The Torture King, the temperature inevitably dropped a little, and we were left with Enigma's bug-eating routine and The Tube regurgitating beer from his stomach, which members of the audience were later invited to drink. Many did so. Curiously, it was The Tube's relatively mild stunts which prompted the greatest gasps of disgust from the audience. Oh sure - now you're appalled!

Watching all this from my spot at the bar, I felt a surge of intense, fiery joy. I was enjoying this show in the same ferocious way I'd enjoyed The Clash's white-hot Plymouth gig in 1977 or The Pogues at the Town & Country. That was a sensation I'd felt at only two or three concerts since, and one which I had started to believe I'd never experience again. And yet, here it was: that thrilling sense that tonight I'd found my way to the very belly of beast. The wild, hi-octane spirit of true rock 'n' roll was abroad that night and if it happened to be embodied by sideshow performers rather than musicians, then so what? This was indeed entertainment, as Jim Rose boasted, which was "live, real, raw and dangerous". And it was big fun. Very big fun indeed.

I know that describing an evening like this in such glowing terms risks making me look like a slavering sadist, but that really isn't the point. Like any good showmen, Rose and his chums pulled in a crowd by promising to give them something they had never seen before. And how often do any of us get a chance to witness that?

It's also worth pointing out that Rose's dark and funny PT Barnum spiel was a big part of the show's success. He would introduce parts of The Torture King's act by warning the audience that they might pass out ("I've seen junkies faint!") or find themselves soaked in blood ("Sometimes he goes off like a geyser!"). When Mr Lifto hoisted the concrete block with his nipples, Rose would hint that terrible damage might result ("Don't rip 'em out, Lifto.") but then make it clear where his true concerns lay (.we need ya tomorrow night!"). Every now and again, he would stress the show's educational aspects by thrusting his forefinger in the air and uttering a sudden cry of "Science!"

In these anaemic times, when ever eating a little animal fat is thought tantamount to suicide, shows like these provide a valuable reminder that we're all a lot tougher than we think we are. And I certainly don't see Lifto and the rest as objects of pity. They seemed sane enough to me, were plainly doing this by choice and gave every sign of thoroughly enjoying their 15 minutes of fame. Where would you rather be: playing to sell-out crowds all over the world, or working some miserable day job?

1) The truth is that human skin really is much more malleable than we imagine. According to Rose in his 1995 book Freak Like Me, The Torture King's Secret was avoiding veins and blood vessels and pulling out the pins slowly enough to let any blood be may had loosed congeal. Mr Lifto, he adds, trained for his own act by expanding his original piercings with heavy-gauge jewellery and practicing till he formed pain-resistant calluses on the areas that bore most weight.

Shane MacGowan ran out of road in September 1991, halfway through a Pogues tour of Japan, where his impossible behaviour on and off stage finally drove his frustrated bandmates to sack him. When this axe finally fell, MacGowan himself seemed more relieved than anything.(1)

The band fulfilled their remaining 1991/92 tour commitments by getting Joe Strummer to guest with them, just as he had when illness prevented Phil Chevron from joining a North American tour in 1987. They released a couple of lacklustre albums without MacGowan and finally called it a day in 1996. MacGowan went on to record one surprisingly good solo album (1994's The Snake) and one rotten one (Crock of Gold in 1997). These days, The Pogues are really just a nostalgia act, reuniting with MacGowan for regular St Patrick's Night and Christmas gigs to canter through their greatest hits. I'm sure they're still a bloody good night out, but there was a time when they were so much more than that.

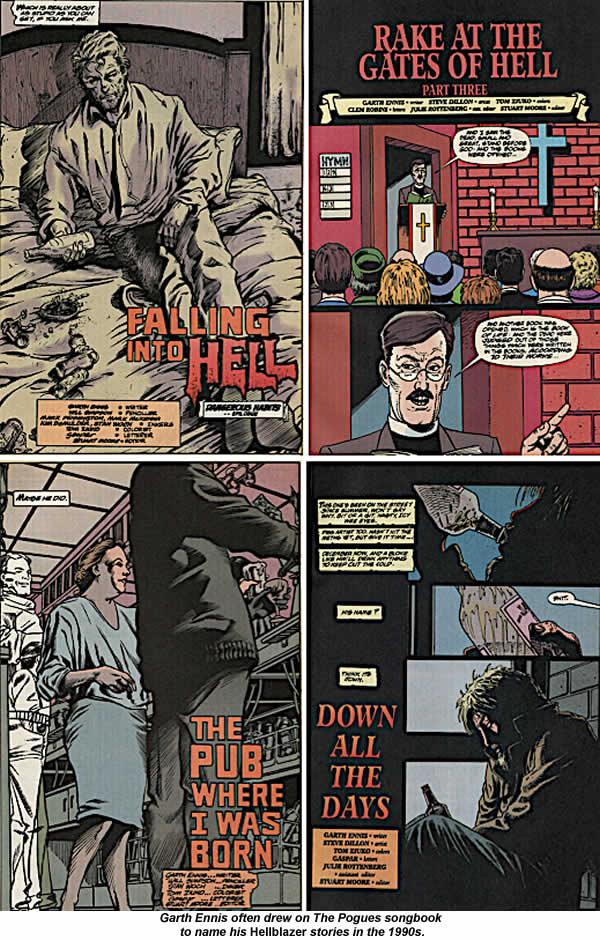

Another aspect of the band's curious after-life came in the work of Belfast-born comics writer Garth Ennis, who began a long run on the Vertigo title Hellblazer in May 1991. The book's main character was a dodgy London occultist called John Constantine who drank in the same tatty pubs I was using myself. He chain smoked, he was often pissed and he'd spent his youth playing in a mid-seventies punk band. Get a couple of pints down in Soho's Blue Posts or the Victoria up in Stoke Newington, and it was very easy to imagine him slumped at the bar beside you.

MacGowan's lyrics made a perfect mental soundtrack to this grubby world and Ennis took every opportunity to plunder them for Constantine tales. Rainy Night in Soho gave him the story title Falling Into Hell and Sally MacLennane contributed The Pub Where I Was Born. MacGowan songs like Down All the Days and Rake at the Gates of Hell gave their names to Hellblazer stories too.

Sometimes, Ennis didn't take his titles from Pogues songs, but simply deployed a snatch of MacGowan's lyrics at key points in the narrative. This happened with both Boys From the County Hell in Hellblazer #80 (".And burn this bloody city down in the summer of the year") and Transmetropolitan in issue #83 ("Goodnight and God bless, now fuck off to bed").

Ennis continued this habit right through his first stint on the book (which ended in 1994). I'd like to think some readers were inspired to check out the source of his quotes and found themselves becoming Pogues fans as a result.

1) Here's James Fearnley, the band's accordion player, describing what drove them to fire MacGowan in his 2012 memoir Here Comes Everybody: "In the course of the past two years, our gigs had been decimated by [Shane's] fits of screaming, his seemingly wilful abandonment of his recollection of the lyrics, his haggard, terror-stricken appeals which we had mistaken for panicked requests for a cue, his maddening and petulant refusals to come out on stage with us. Jem lamented the fact that Shane no longer accompanied us anywhere, preferring to shut himself in his room, appearing only at show time, more often than not with seconds to spare and hardly in a condition to do much."

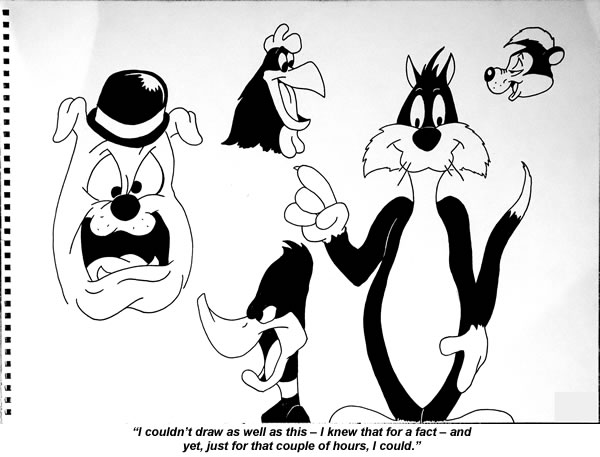

OK, this is a weird one. I can't put an exact date on it, but I was sitting alone at home one night in Finsbury Park when I decided to pass some time by trying to copy a few of the character drawings in Steve Schneider's That's All Folks: The Art of Warner Bros Animation.

The circumstances could not have been less promising. I was slumped in my armchair, awkwardly propping Schneider's open A4 book on one knee and my own A3 sketchpad on the other. All I had to draw with was a bog-standard felt tip, and I knew full well that I couldn't draw anywhere near well enough to get the Warner Brothers characters right anyway. (1)

And yet, just for the next couple of hours, I couldn't put a foot wrong. I made no attempt to pencil any of the figures first, but simply started copying them from the book in ink. Every mark I made on the paper fell perfectly in place, and every line followed precisely the path required. I felt more like a spectator than anything as I watched all this unfold - it was an almost mystical experience.

One by one, Spike, Foghorn Leghorn, Sylvester, Pepe and Daffy all appeared beneath my pen, each one realised with a perfection I've never come close to before or since. I couldn't draw as well as this - I knew that for a fact - and yet, just for that couple of hours, I could. Then the spell snapped off again and I was back to my old cack-handed self.

All writers know the feeling of being "in the zone", a rare trance-like state when the words flow painlessly through you on to the page with easy grace. It seems to be a question of finally managing to get out of your own way, and I can only assume something similar happened here. If it weren't for the concrete evidence the evening left behind, I'd honestly think I must have dreamt the whole thing.

1) Believe me, this is NOT false modesty. Something like the face at the top of this page is normally the very best I can do as far as drawing's concerned - and that's a world away from the clean, elegant lines of the Warner Brothers characters.

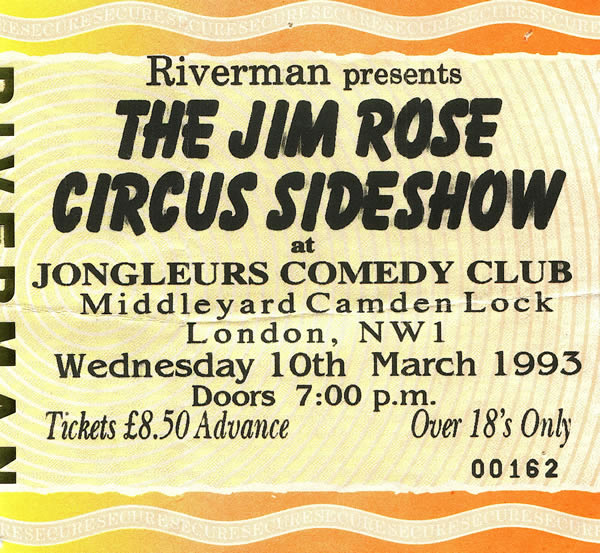

I next saw the JCRS at Jongleur's in Camden Lock in March 1993, then at a couple of shows on their 1995 UK tour. "Thrills, chill and doctor's bills," it promised in the press ads.

All I can remember now about the Jongleurs gig is that Lifto came on stage wearing a Suede T-shirt, acknowledging his support for what was then London's hippest and most provocative new band. Suede's songs were all about life's sleazier pleasures, which made their shirt a perfect fit for Lifto's act. (1)

The 1995 Watford gig was my first chance to see a new routine Rose called the Jim Rose Chainsaw Stunt Team, which began with him, Lifto and a new performer called Mark the Knife juggling three active chainsaws on stage. Then came the evening's grand finale.

Rose announced he was about to plunge the auditorium into darkness and told us it was imperative we all remain seated when this happened. Lifto and Mark would then don miners' helmets with lights on the front and run up and down the aisles passing their still-active chainsaws just inches over our heads. Before anyone had a chance to react, the lights snapped off and the hall was suddenly full of noise. I could hear roaring chainsaws, running feet, sirens and the occasional scream, but see only the illuminated bulbs of the miner's helmets dashing about. Seated as I was just one chair from the aisle, I thought it best to sit very still indeed.

Rose describes this routine in Freak Like Me - though here he's discussing an earlier gig in Australia. "There's nothing like a power tool coming your way in the dark to put the fear of God into you," he writes. "Just as the audience were clasping their hands to pray, all hell broke loose. [.] Enigma bolted towards them, waving a siren with a red flasher. Bebe and Rubberman grabbed high-powered squirt guns and spritzed the audience with cold water, Mark the Knife continued terrorising the front row with his chainsaw and he was even scarier in the dark. All the while I'd yell into the mike, 'Scream if they get too close'. Screams begat screams." (2)

Shepherds Bush, four days later, was the tour's final stop. Rose had barely started the tamest preliminaries of his own routine there - such as his Human Blockhead act - when a young lad standing just in front of me fainted dead away and hit the floor. His girlfriend, clearly a more resilient soul, looked utterly disgusted with him when this happened and even more so when the bouncers arrived to carry him outside. After a brief struggle with her conscience, she decided she'd better go with him. A monstrous biker greeted this sight by shoving his tattooed and pierced face into mine, clenching his fists and screaming a triumphant, "Yeesss!!!" Couldn't agree more, mate. Good, wasn't it? (3)

After the show, I queued with the rest of the fans to get my newly-purchased "Freak" T-shirt signed by Rose, Bebe and the rest. Two teenage girls waiting with me at the lip of the stage took this opportunity to shout "Get your cock out" at Mr Lifto. He patiently replied that he'd finished work for the night and that, if they wanted to see the item in question again, they'd have to come back for tomorrow night's show. I'd seen enough of Jim Rose audiences on both sides of the Atlantic by then to realise that it was always the girl-next-door types who wound up baying for blood and nudity the loudest. (4)

When my turn for a signature came, I climbed the stage steps next to Rose and started babbling about my memories of the Washington gig. He gave me a cool glare indicating that, by stepping on to his stage without invitation, I'd come just a little too close for comfort. There was a lot of authority in that glare, so I reversed hastily back down the steps and order was restored.

Next day, I happened to be passing the giant HMV store opposite Poland Street in central London, when I spotted The Enigma there shopping with a friend. He was covered from to head to foot with a tattooed jigsaw puzzle, some pieces of which he'd already started filling in with solid ink. Half-naked on stage - which is how I was used to seeing him - he made a very striking spectacle, but fully clothed in Oxford Street with a hat pulled low over his eyes, he was just one more bloke out buying CDs. So that's what someone who "blurs the line between man and monster" does on his day off.

1) For my own T-shirt that night, I chose the Jim Rose one I'd bought at the 9:30 club, confident in the knowledge that very few London fans would have had the chance to acquire this Eyeball Terrorist tour design. "Where'd you get the shirt, mate?" a bloke to my left gratifyingly asked as I entered the hall. "Washington," I smugly replied.

2) Walking back to the station after this show, I noticed something wet in my hair and gave it a sniff to see what it was. I know now that this must have been simply water from one of the squirt guns Rose mentions, but at the time I persuaded myself it smelt like motor oil, thrown out by the blades of a perilously nearby chainsaw. That's the power of suggestion for you, folks.

3) "A faint," Rose explains in Freak Like Me, "is a falling ovation".

4) I wonder if this is because they're under such constant pressure to behave with ladylike decorum in the rest of their lives? Give them a glimpse of Lifto's act and it's like a hen party squared.

Like everyone else, I greeted the announcement of this gig with considerable scepticism. Here was the band which had inflamed us all into a crusade against fat, bloated, irrelevant rock stars coming together again 20 years after their prime to headline an open-air event in front of 30,000 worshipping fans, each of whom was asked to pay £22.50 for admission. Surely the only proper response was a contemptuous sneer?

On the other hand, this was the Sex Pistols, undeniably the most important band of their generation, and one of the very few significant punk acts I'd never seen live. The Pistols' 1976 Anarchy tour had played a Plymouth club called Woods just nine months before I moved to the city and that near-miss still rankled with me. Finsbury Park was just a short walk from my front door and Iggy Pop had been booked as the day's main support act. I'd never seen him live either and quite fancied the chance to do so. Somewhat shame-facedly, I shelled out my £22.50 and bought a ticket.

When the day dawned, I filed in through the park's main entrance with all the other punters, found a spot near the back of the crowd and spent most of my afternoon wandering back and forth between there and the beer tent. When Iggy came on, I shouldered my way through to somewhere near the front of the stage and threw myself into the moshpit. I'd been pogoing around there for only a few minutes when I started to feel like I was going to have a heart attack and had to reverse my way back to a calmer section of the crowd. Twenty years earlier, I'd have spent most of Iggy's set in that moshpit and the songs would have just flown by. Now I could barely stand the pace for two numbers. When had I become so old?

No such concerns bothered Iggy himself. He was 49 at the time - ten years older than me - but he threw himself around that stage for a solid hour with all the energy of a hyperactive toddler. As I watched his slim, muscular, shirtless form cavorting about, I remembered the sight of Keith Richards at Wembley back in 1982, and felt exactly the same surge of jealousy all over again. Double bastard!

The Pistols took the stage in front of a backdrop of giant newspaper headlines drawn from the hysterical tabloid coverage of their 1976 TV appearance with Bill Grundy. Prominent among these was the Daily Express front page which gave this tour its name: "Punk? Call it Filthy Lucre". Thankfully, their singer made no attempt to impersonate his Faganesque younger self, choosing instead to stroll sedately around the stage in a tablecloth-check shirt with his hair teased into a sarcastic crown of bleached blonde spikes. "It's Johnny and the boys," he announced. "Fat, 40 and back".

That set the tone for the whole set. No-one was taking this occasion terribly seriously - least of all the band themselves - so there were no great expectations to fulfil and no risk of disappointment if those expectations weren't matched. In the event, Pistols '96 weren't too bad at all. Steve Jones' guitar sound was as admirably crunchy as ever, Rotten/Lydon managed to remember all the words and there was nothing wrong with Glen Matlock and Paul Cook's rhythm section either. If you closed your eyes for a second, you could almost believe you were hearing the band at its 1970s peak, rather than enduring the third-rate tribute act we'd all feared would turn up instead.

They opened with Bodies, going on to play their four classic singles and most of Never Mind The Bollocks. I rejoined the moshpit for Anarchy In The UK, but retreated again immediately afterwards. The band stayed on stage for about an hour (encores included) and bade us farewell with a ramshackle version of Iggy & The Stooges' No Fun. I'd hoped they might invite Iggy out to join them on this particular number, but no such luck.

Next day, I ran into my lodger Duncan, who told me he'd refused to buy a ticket for the gig but managed to get in anyway. He'd been milling around with a crowd of other excluded fans outside the security fence till the end of Iggy's set, when someone managed to break a section of that fence down. Duncan rushed in along with everyone else and had therefore seen the Pistols perform for nothing while I'd paid through the nose. His punk credentials were left gleaming by this episode, while mine looked very sorry indeed. I felt even older after that.

The Academy was already swarming with sullen-looking Cave fans when I arrived, most of whom had taken pains to make themselves look as debauched as possible. Skin was worn with a pasty white pallor and every item of clothing just had to be black. Everywhere I looked, I saw hair teased into alarming vertical sculptures and make-up which had been applied with both haste and vigour. If you wanted to call them Goths, I wouldn't be inclined to argue with you. (1)

When Cave and the band came on, they played like demons. Their performance was supremely tight, sharply focussed and delivered with apocalyptic force. Cave himself, dressed in a black pinstripe suit, spent much of the gig with one pencil-thin leg propped against his stagefront monitor, leaning forward to bark his lyrics into a hand-held microphone at the thrashing crowd beneath.

The Murder Ballads album had been out for only about six months at this point, and the band book-ended their set with that record's Stagger Lee at the beginning and O'Malley's Bar at the end. Sandwiched between those numbers, we got a judicious selection of their earlier work, including Do You Love Me?, Red Right Hand, The Weeping Song and The Mercy Seat. They also reviewed Into My Arms and Black Hair from what would become their 1997 album The Boatman's Call. (2)

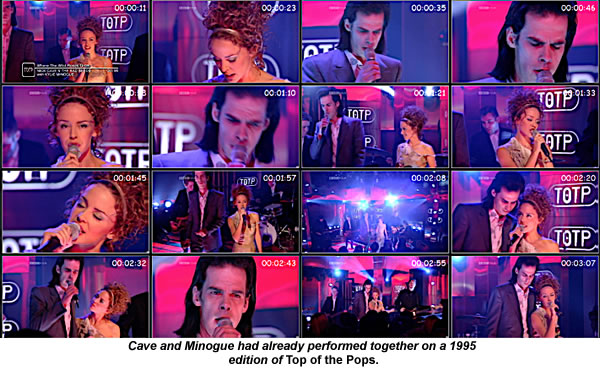

When the time came to play Where The Wild Roses Grow - another Murder Ballads track, of course - Cave announced a special guest and Kylie Minogue came bouncing on from the wings, giving us all a cheery wave and a 100W smile as she walked across the stage. The crowd was about as far from her core audience of shiny pop kids and kitch-loving gay men as its possible to get, but already she'd won us over.

Many of the arch-miserabalists at the Academy that night would have been smack in the middle of Kylie's school-age demographic when she'd had her first hits back in 1988, and her appearance on stage seemed to take them straight back to those carefree days when coloured clothes were still a possibility and a spot of sun did not shrivel them to ashes. "It's Kylie!" they seemed to be thinking. "And she's smiling at us!"

The moment soon passed of course, but while it lasted it really was rather sweet. Then Kylie slotted herself into Cave's arms and smiled blissfully up at him as he sang about bludgeoning her to death with a rock.

1) Cave's audience was a much Gothier bunch back then. It was only with 1997's The Boatman's Call that he began reinventing himself as a mature, sophisticated balladeer along the lines of late-period Leonard Cohen.

2) Years later, I interviewed The Bad Seeds' Mick Harvey, who told me what a hell of a job they'd had finding the right spot for Stagger Lee in the band's set. "It's so out of step with the other material," he explained. They eventually solved this problem by making the song one of their regular encores, which allows it to stand slightly apart from everything else. Back in 1996, they were evidently still experimenting - in this case by making Stagger Lee their opening number.

The Harringay Arms in Crouch End was one of my favourite pubs when I lived up that way. It was a thin, rectangular room, with its short edge opening on to Crouch Hill and a bar lining most of the long right-hand wall. Opposite the entrance, at the far end of the room, there was a dartboard, a TV bolted to the wall (always tuned to either racing or football) and a table in the corner full of old boys who seemed to have been drinking there since early adolescence. The smoke of a thousand roll-ups had stained the ceiling immediately above them a grubby shade of nicotine brown.

Dave Stewart's recording studio - a converted church - was just three doors away from the Harringay, so now and again you'd also find some up-and-coming band dropping from in there in to kill a bit of time while they complained about whichever member wasn't present. All this made for an interesting mix of people, and one which is far harder to find in London pubs today. I always made a point of taking friends from outside London to the Harringay when they visited, and often dropped in there on my own for an hour or two to have a few beers while I read a book.

On this particular night, I was reading Victor Bockris's 1998 memoir Muhammad Ali in Fighter's Heaven, an account of the writer's stay with Ali at his Pennsylvania training camp in 1973/74. I'd only intended to stop in for a hour on my way home from a meeting up at Alexander Palace, but I was enjoying the book so much that I just stayed put. Chapter followed chapter and pint followed pint. Small wonder, then, that by 9:00pm or so I was starring to feel distinctly pissed.

That's when I noticed a new arrival was causing some sort of commotion at the other end of the bar. I squinted over and saw it was Suggs, the lead singer of Madness, who (as I later discovered) had been working on his first solo album at Stewart's studio and decided he fancied a pint before going home. I'd seen Madness play live way back in 1979 and loved their cheeky, music hall approach to English pop in the chart-topping years that followed. Under different circumstances, I'd have loved to have a chat with Suggsy, but I had no wish to repeat the Alan Moore debacle of ten years earlier, so I decided to play the jaded Londoner and keep my mouth shut instead. Pop stars? Get 'em in here all the time, mate.

Half an hour later, I glanced up to find Suggs wedged at the bar next to me - the only vacant spot - and asking if the book was any good. I said, yes, it was excellent and we got talking about what a brilliant bloke Ali was. I'd just seen Leon Gast's 1996 Ali documentary When We Were Kings so, what with that and the book as well, I had plenty to say on the subject. How much sense I was making by this point in the evening, I don't know, but there was loads of information in there somewhere.

All this time, I'd dealt with the Alan Moore problem simply by refusing to acknowledge that I knew who I was talking to. Eventually, Suggs took the initiative and started to introduce himself. I told him that I knew perfectly well who he was, but that I'd thought it best to avoid all the usual fannish palaver. "You don't want all that old bollocks," I said. He seemed to accept this explanation and we went back to talking about Ali.

We chatted for another 20 minutes or so, then Suggs went off to talk to somebody else and I decided I'd better go home. Noticing my somewhat unsteady progress towards the door, he took a moment to come over and make sure I was OK before saying goodnight. The man's a gent.

Purely by chance, my stay in Nashville coincided with The Southern Festival of Books, a three-day publisher's fair which I discovered setting up opposite my hotel on the Friday I arrived.

Two of the most interesting-sounding sessions were booked for the next day. A sociology professor named Jay Howard would be talking about his book Apostles of Rock, which he'd subtitled The Splintered World of Christian Contemporary Music, then it was former Sunday Times editor Harold Evans on his own latest volume The American Century. If I skipped the audience Q&A at the end of Howard's talk, I calculated, I'd just have time to grab a lunchtime sandwich before going back to hear Evans.

Howard started his session by explaining just how fractured Christian Contemporary Music (or CCM) had become. There was Separational CCM like DC Talk, Integrational CCM like Amy Grant and Transformational CCM like Terry Scott Taylor. Each of these categories was peppered with sub-genres, creating hybrid forms like Integrationalist Transformational. A class of schoolkids in their early teens, dragged along to the talk by their teacher, dutifully wrote all this down. They gave every sign of being bored out of their minds by the whole subject, but I thought it was fascinating. Even British dance music hadn't spawned this many factions!

Howard went on to explain that some hard-line Christian rockers liked to police their rivals be imposing a "JPM" count on every song - which stands for "Jesuses per Minute", of course. Fail to mention Christ in every verse and you were immediately dismissed as a lily-livered atheist. Other CCM groups - the Integrationalist ones, I suppose - favoured what he called "Jesus is my girlfriend" songs. By this, he meant they wrote cross-over lyrics that could be taken as a conventional love song by the mass market, but which the cognoscenti knew were really about Christ.

Howard played a brief snatch of music from each of the artists he mentioned - some of which wasn't bad - and handed out a factsheet with extracts from their lyrics. Among the verses he cited there were these two from a DC Talk song called Jesus Freak:

Separated, I cut myself clean,

From a past that comes back in my darkest of dreams,

Been apprehended by a spiritual force,

And a grace that replaced all the me I've divorced.

Kamikaze, my death is gain,

I've been marked by my maker - a peculiar display,

The high and lofty, they see me as weak,

'Cause I won't live and die for the power they seek.

Reading these particular lyrics, it struck me that much of their language - "kamikaze", "my death is gain", "darkest of dreams" - could just have easily have appeared in a death metal song, yammered out by band of teenage Satanists. Whether young American musicians were using their songs to declare an allegiance to Christ or to try and shock their parents by denying him, the imagery they chose seemed much the same. (1)