“She fell down on her bended knees,

“She fell down on her bended knees,

For mercy she did cry,

‘Oh Willie dear don't kill me here,

I'm unprepared to die’,

“She never spoke another word,

I only beat her more,

Until the ground around me,

Within her blood did pour.”

- The Knoxville Girl, Charlie Louvin (2007).

It's the fragility of Charlie Louvin's voice that does it. He was 79 years old when he entered a Nashville studio to re-record Knoxville Girl for his self-titled 2007 album, and he sounds like a breath of Tennessee wind could blow him away. There's a palpable sadness in his voice as Louvin's character confesses his old crime, but absolutely no attempt to excuse what he's done. The result is one of the most exquisite readings the song's received in its 80-year history on disc.

Like almost every other version, Louvin's sticks closely to the template set by Arthur Tanner on the song's first commercial release in 1925. Knoxville Girl was already well-known in the South by the time Tanner's record came out, but it was his Columbia 78 which froze it in its enduring form. The version of events Tanner gave us has been adhered to by almost every singer who followed him, and it goes like this:

The narrator meets a girl in Knoxville and spends every Sunday evening at her house. One day, they go for walk and he begins beating her with a sturdy stick. She begs for her life, but he ignores her pleas, continues the beating even more viciously, and doesn't stop till the ground is awash with her blood. He dumps her dead body in the river, then returns home, fending off his mother's queries about his stained clothes by insisting he's had a nosebleed. After a tortured night, he's thrown in jail for life. His last words before the music fades out are to assure us that he really did love her.

Louvin first tackled this grim little tale with his brother Ira in 1956, when they worked as a bluegrass duo called The Louvin Brothers. But Ira's long-dead now, and Charlie's partner for the 2007 session was Will Oldham, better known as Bonny “Prince” Billy, who wasn't even born until 14 years after Charlie and Ira first put the song to disc. Wisely, Oldham doesn't try to mimic the blood-born harmonies the brothers produced then, contenting himself instead with some restrained background singing and few lines of the lead vocal when Charlie takes a breather.

Despite the 43-year difference in their ages, the two men clearly see the song through very similar eyes, and that's one clue to why it's survived so long. Like a shark, Knoxville Girl seems to have reached a peak of evolution many generations ago, finding an unchanging form which suits each new decade as well as the last. Young singers find the song just as irresistible as their grandfathers did, and show just as little inclination to meddle with its established form.

For evidence of this point, just check iTunes. Apple added five brand new versions of the song to its stock in the first six months of 2009 alone, from artists as young as the twenty-something Rachel Brooke, as unexpected as former London punk JC Carroll (late of The Members) and as telegenic as the country singer Ruth Gerson. Most stick closely to the song's classic form, with Brooke adding a layer of faux surface noise to underline her respect for its roots, The Fox Hunt producing a faithful string band version, and Gerson refusing to water down its sheer nastiness.

Knoxville Girl's long back-catalogue continues to find new buyers too, with the same six months bringing re-released versions by The Wilburn Brothers from 1958, Mac Wiseman from 1975 and The Louvins themselves. And if iTunes alone has all that, then how many other versions must have been recorded in the same period without ever reaching Apple's virtual shelves?

So, nearly a decade into the 21st Century, and it's clear that everyone still wants a piece of this unfortunate lass. Even now, though, when you play the song to someone who hasn't heard it before, they all ask the same question: why did he kill her?

The song certainly doesn't spell out any motive, moving from an innocent country walk to the start of the beating in two consecutive lines. The Louvin Brothers' 1956 lyric – which I'm going to use as my model throughout this piece – puts it like this:

“We went to take an evening walk,

About a mile from town,

I picked a stick up off the ground,

And knocked that fair girl down.” (1)

It's as simple and as brutal as that: one minute they're walking quietly along, the next he's bludgeoning her with a makeshift club. To see why he's doing this, we have to consider some clues from the rest of the song. Take this couplet from the opening verse:

“And every Sunday evening,

Out in her home I'd dwell.”

Then there's the victim's words as she begs for mercy:

“Oh Willard dear, don't kill me here,

I'm unprepared to die.”

And finally, this verse:

“Go down, go down, you Knoxville Girl,

With the dark and roving eye,

Go down, go down, you Knoxville Girl,

You can never be my bride.”

Put these three fragments together, and things begin to get a little clearer. The killer didn't just visit this girl's home on Sunday evenings, he dwelt there, which carries a definite suggestion that he stayed the night. Faced with imminent death, the girl says she's “unprepared to die”, which tells us she's not yet had a chance to make her peace with God about some recent sin that's troubling her mind. Her “dark and roving eye” hints that - in the killer's mind at least - she's a bit of a temptress. Although she can now never be his bride, that possibility's evidently been raised, or why else would he mention it?

So, we've got a young man who's slept with his girlfriend, come under some pressure to marry her, and then kills her instead. To see how he reached that extraordinary decision, we need to rewind the clock to 17th Century Shropshire and two of that century's English diarists.

Philip Henry was a non-conformist clergyman living about 20 miles from the Shropshire town of Shrewsbury – then also called Salop. On February 20, 1683, he wrote this in his diary:

“I heard of a murther in Salop on Sabb. Day ye 10. instant, a woman fathering a conception on a Milner was Kild by him in a feild, her Body laye there many dayes by reason of ye Coroner's absence.” (2)

Philip Henry was a non-conformist clergyman living about 20 miles from the Shropshire town of Shrewsbury – then also called Salop. On February 20, 1683, he wrote this in his diary:

“I heard of a murther in Salop on Sabb. Day ye 10. instant, a woman fathering a conception on a Milner was Kild by him in a feild, her Body laye there many dayes by reason of ye Coroner's absence.” (2)

Under the Julian calendar, which then prevailed in England, February 10, 1683, was indeed a Sunday. Henry is a contemporary local witness describing something that happened very recently, so there's good reason to take his account seriously.

The next piece of the puzzle comes from the third volume of Samuel Pepys' collected ballads, which covers the period from 1666 to 1688. Pepys was a keen collector of the printed broadsheet ballads which were then sold on every London street corner, and amassed over 1,800 examples in his personal archive. Somewhere around 1685, he added one called The Bloody Miller, which came complete with this introduction:

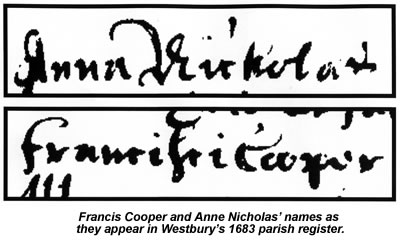

“A true and just Account of one Francis Cooper of Hocstow near Shrewsbury, who was a Miller's Servant, and kept company with one Anne Nichols for the space of two years, who then proved to be with Child by him, and being urged by her father to marry her he most wickedly and barbarously murdered her.” (3)

Sounds familiar, doesn't it? Hocstow, is a 17th Century spelling of Hogstow, a village about 12 miles south-west of Shrewsbury, so the place, the killer's profession, the date and the deed itself all match Henry's account. It's fair to conclude that both documents are describing the same crime, and now we can put a name to each of the main players. The murderer was called Francis Cooper, his victim was Anne Nichols, and he killed her because he'd knocked her up and didn't want to marry her.

The lyrics of the ballad itself give us the remaining details. A young miller spots an attractive girl in his home village and, despite her virtuous nature, persuades her to sleep with him. She discovers she's pregnant, and her father sends her round to the miller's cottage to demand he marries her. The miller suggests they find a quiet country spot where they can discuss the matter in private. He then murders her horribly and is eventually hanged for the crime.

The similarities with Knoxville Girl's plot are striking enough, but it's the wording and scansion of the two songs that really establishes The Bloody Miller as Knoxville Girl's earliest ancestor. Before we come on to that aspect, though, we need to look at another old English ballad too.

Gallows ballads like The Bloody Miller were a popular form in Pepys' day, and often claimed to be an authentic record of the killer's last confession or his dying words on the scaffold. These were composed by workers in London's print shops, run off the presses the night before the execution and sold at the base of the gallows itself while the hanged man's body was still swinging. The goriest ballads tended to sell particularly well, and would be endlessly rewritten and adapted to extend their shelf life, often incorporating local details or adapting themselves to new atrocities as time passed and the sellers travelled from town to town.

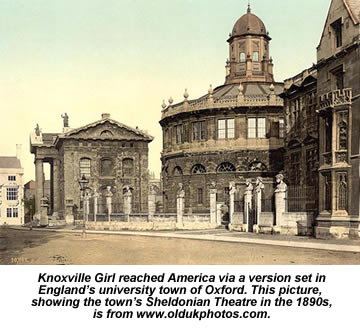

The Bloody Miller spawned other ballads very quickly, and the most significant of these is The Berkshire Tragedy. The National Library of Australia has a copy printed in 1744, but it's probably a good deal older than that. The ballad tells the same basic story as The Bloody Miller, but sets its tale in Wytham, just across the border from Berkshire in the next-door county of Oxfordshire. It also adds several new elements to the tale which are not present in The Bloody Miller, but which crop up again half a century later in the first versions of Knoxville Girl. Most significantly of all, The Berkshire Tragedy's narrator describes his victim as “an Oxford lass” - Oxford's about four miles from Wytham - and that's a development we'll return to later.

It's not clear whether The Berkshire Tragedy was a simple rewrite of The Bloody Miller, with these changes brought in simply because its composer hoped they'd make the thing sell better, or whether they're facts imported from a real Berkshire murder at around that time. If it's the latter, then even this early version of the printed ballad may be an amalgam of two quite separate crimes. I can't explain why it's called The Berkshire Tragedy when neither of the main characters lived there, but perhaps The Oxfordshire Tragedy was simply thought too unwieldy a title.

It's not clear whether The Berkshire Tragedy was a simple rewrite of The Bloody Miller, with these changes brought in simply because its composer hoped they'd make the thing sell better, or whether they're facts imported from a real Berkshire murder at around that time. If it's the latter, then even this early version of the printed ballad may be an amalgam of two quite separate crimes. I can't explain why it's called The Berkshire Tragedy when neither of the main characters lived there, but perhaps The Oxfordshire Tragedy was simply thought too unwieldy a title.

So. Let's recap for a moment. We've got The Bloody Miller, collected by Pepys in around 1685, complete with an introduction giving the killer and his victim's names, plus an independent contemporary account of the crime itself. By 1744, this ballad had produced an alternative version called The Berkshire Tragedy, which adds many of the details we're familiar with in Knoxville Girl today, but which may also draw on a second crime quite separate from the one Pepys' ballad describes.

The ballad scholar GM Laws draws precisely this family tree for Knoxville Girl, linking it directly back to 17th Century England. “The ballad in all its forms preserves the same stanzic pattern, the same basic sequence of events, many of the same descriptive and narrative details, and even the same phrases and rhyming words,” he says. (4)

The clearest way to illustrate this point is to assemble a composite version of The Bloody Miller and The Berkshire Tragedy, using the two English ballads' original wording, but setting each verse against its equivalent in the American song. The result looks like this:

The Bloody Miller (c. 1685) /

The Berkshire Tragedy (1744)

| “By chance upon an Oxford lass, | } | |

| I cast a wanton eye, | }B | |

| And promised I would marry her | }T | |

| If she with me would lie. | } | |

| “Thus I deluded her again, | } | |

| Into a private place, | }B | |

| Then took a stick out of the hedge, | }T | |

| And struck her in the face. | } | |

| “But she fell on bended knee, | } | |

| For mercy she did cry, | }B | |

| ‘For heaven's sake don't murder me, | }T | |

| I am not fit to die’ | } | |

| “From ear to ear I slit her mouth, | } | |

| And stabbed her in the head, | }B | |

| Till she poor soul did breathless lie, | }M | |

| Before her butcher bled. | } | |

| “And then I took her by the hair, | } | |

| To cover the foul sin | }B | |

| And dragged her to the river side, | }T | |

| And threw her body in. | } | |

| “Thus in the blood of innocence, | } | |

| My hands were deeply dyed, | }B | |

| And shined in the purple gore, | }T | |

| That should have been my bride. | } | |

| “Then home unto my mill I ran, | } | |

| But sorely was amazed, | }B | |

| My man thought I had mischief done, | }T | |

| And strangely on me gazed. | } | |

| “‘How came you by that blood upon, | } | |

| Your trembling hands and clothes?’ | }B | |

| I presently to him replied | }T | |

| ‘By bleeding at the nose.’ | } | |

| “I wishfully upon him looked, | } | |

| But little to him said, | }B | |

| I snatched the candle from his hand, | }T | |

| And went unto my bed. | } | |

| “There I lay trembling all the night, | } | |

| For I could take no rest, | }B | |

| And perfect flames of hell did flash, | }T | |

| Like lightening in my face. | } | |

| “The justice too perceived my guilt, | } | |

| Nor either would take bail, | }B | |

| But the next morning I was sent, | }T | |

| Away to Reading gaol.” | } | |

| “So like a wretch my days I end, | } | |

| Upon the gallows tree, | } | |

| And I do hope my punishment, | }B | |

| Will such a warning be, | }M | |

| That none may ever after this, | } | |

| Commit such villany.” (3, 6) | } |

The English ballads are a lot more long-winded than their American cousin, and tend to go in for a lot more moralising. But cutting all this out, as I've done above, still leaves all the key elements of Knoxville Girl in place. The private walk's there, and so's the stick, the plea for mercy and the fact that she's not yet made her peace with God. The sadism of the killing itself is present too, as are the hair, the river, the forestalled wedding, the return home, the nosebleed, the candle, the restless night, the trip to jail and the bad end.

One element which was lost when the English ballads started to be shortened was an unambiguous statement of what caused all the trouble. The Bloody Miller has:

| “She did believe my flattering tongue, | ||

| Till I got her with child”.3 |

And The Berkshire Tragedy says:

| “The damsel came to me and said, | ||

| By you I am with child, | ||

| I hope dear John you'll marry me, | ||

| For you have me defiled”.(6) |

Whoever put the earliest versions of Knoxville Girl together retained the source ballads' scansion, and that means the composite version above can be sung to Knoxville Girl's modern tune. Any musicians out there are looking for a novel take on the song might like to see the verse-by-verse comparison I've put together here (PDF).

Set out like this, The Berkshire Tragedy looks much more significant than The Bloody Miller, accounting for 40 lines against the Miller's ten. But it's worth remembering that, without The Bloody Miller, there'd be no Berkshire Tragedy in the first place. It's The Bloody Miller which is most directly connected to the real Anne Nichols' death, and which first coined this whole family of songs' most distinctive and enduring image. Here's how The Bloody Miller puts it:

| “My bloody fact I still denied, | ||

| Disown'd to the last, | ||

| But when I saw this for my fact, | ||

| Just judgement on me passed, | ||

| The blood in Court ran from my nose, | ||

| Yea, ran exceeding fast.” |

Every later version, starting with The Berkshire Tragedy, shifts this scene to the killer's return home, where he uses the nosebleed excuse to fob off questions about his blood-stained clothes. The Berkshire Tragedy verse above has him holding this conversation with a servant, but that would hardly have been a credible circumstance for the early Scottish and Irish settlers who first brought this song across the Atlantic. Knoxville Girl sets the conversation in simple family surroundings, having the killer confronted by his worried mother:

| “Saying ‘Son, what have you done, | ||

| To bloody your clothes so?’ | ||

| I told my anxious mother, | ||

| I was bleeding at my nose.” |

This idea recurs in almost every version of Knoxville Girl, and it's the single most reliable DNA “signature” establishing that all the branches of this song's family tree lead back to The Bloody Miller's trunk. In its first usage, the nosebleed in court may have been intended as an omen of the killer's ill fortune – in this case, his imminent execution.

This is a belief from English folklore which goes back at least as far as 1180, when Nigel de Longchamps' Mirror for Fools has a character interpreting his nosebleed as a sign of bad luck to come. The same idea appears again in John Webster's Duchess of Malfi from 1614 and in Samuel Pepys' 1667 diary. On July 6 that year, Pepys writes: “It was an ominous thing, methought, just as he was bidding me his last Adieu, his nose fell a-bleeding, which run in my mind a pretty while after.” (6, 7)

We know this notion was still current when The Bloody Miller was written, because 1684 also produced The Island Queens, a play by the restoration dramatist John Banks with this exchange:

We know this notion was still current when The Bloody Miller was written, because 1684 also produced The Island Queens, a play by the restoration dramatist John Banks with this exchange:

“DOWGLAS: ‘No sooner was I laid to rest, but just three drops of blood fell from my nose, and stain'd my pillow.’

QUEEN MARY: ‘That rather does betoken some mischief to thyself.’

DOWGLAS: ‘Perhaps to cowards, who prize their own base lives. But to the brave, ‘tis always fatal to the friend they love.’”

Anyone who beats a woman to death while she's carrying his child would certainly count as a coward rather than a brave man, so perhaps that's the idea The Bloody Miller's original composer was trying to convey. Then again, maybe Francis Cooper really did suffer a nosebleed in the dock, and this was included in the ballad merely as a nice little authenticating detail for those who'd heard accounts of his trial elsewhere. Either way, the nosebleed is now cemented deep into Knoxville Girl's foundations, and it's still the surest sign of every variation's parentage.

Once The Berkshire Tragedy had got the process underway, The Bloody Miller quickly spawned a dozen competing versions of its basic story. These had titles like The Cruel Miller, Hanged I Shall Be, The Wittham Miller or Ekefield Town, and all reported the killer's nosebleed when he returned home. All these songs circulated in parallel with one another, and continued to sell well. The Berkshire Tragedy itself was still being hawked around London as late as 1825, when a printed copy was fraudulently retitled to claim the crime had happened just a few months before.

Recycling like this was part and parcel of the ballad seller's trade. “The ballad printers of America and Britain ransacked the old ballad sheets for anything that was usable,” Laws says. “Frequently, an archaic ballad could be given local application, or could be redesigned to fit a predetermined amount of space.”

It's anybody's guess which version of the song reached America first, but the strand I'm going to follow is the one which started with The Berkshire Tragedy's description of its victim as “an Oxford lass”. We don't know exactly when a version called The Oxford Tragedy first appeared. But, given The Berkshire Tragedy's unambiguous setting in Oxfordshire and the fact that the two counties are right next door to each other, the transposition must have suggested itself almost immediately.

Laws suggests that The Oxford Girl appeared full-blown in the US, perhaps as a variation of Ireland's similarly-named Wexford Girl, which again derives from The Bloody Miller. To me, it makes much more sense to imagine an English version of the song called The Oxford Tragedy morphing into The Wexford Murder for Irish consumption, and then both songs crossing the Atlantic to establish a foothold there. Singers in the New World would presumably have been imagining Oxford, Mississippi, rather than Inspector Morse's dreaming spires, but the song was none the worse for that.

The first proven American original we have is The Lexington Miller, printed as an early 19th Century broadsheet in Boston, and currently held by the Harvard College Library. This describes a miller in Lexington, Kentucky, who promises to marry a local girl if she'll sleep with him. We all know what happens next, and events here unfold just as they did in The Berkshire Tragedy a century before.

Unlike later American versions, The Lexington Miller retains many of The Berkshire Tragedy's less important details, such as the Devil tempting our narrator to commit murder, the victim's sister accusing him and the killer's final execution. Once again, though, it's got exactly the same metre we know today from Knoxville Girl, as a couple of sample verses will demonstrate:

“Now she upon her knees did fall,

Most heartily did cry,

Saying ‘Kind Sir, don't murder me,

I am not fit to die’.

“I would not harken to her cries,

But laid it on the more,

Till I had ta'en her life away,

Which I could not restore.” (4)

My own theory is that the various places where the song touches down - Oxford, Wexford, Lexington, Knoxville - are determined more by that “X” sound in their names than by any more subtle consideration. Once The Berkshire Tragedy's Oxford lass found her way into the title and lyrics, any place name lacking that distinctive consonant simply sounded wrong, and it's a tradition the song's offspring have obeyed ever since.

Whatever the reason for its precise location, by the early 1800s America's singers had a bloody miller of their own. All they needed now was a home-grown murder they could tie into the song and, by the end of the century, they'd found one.

Mary Lula Noel lived with her parents in Pineville, Missouri, about eight miles from the town which bore her family's name. On Wednesday, December 7, 1892, she was staying with her sister, Mrs Sydney Holly, at the Holly family's nearby home, when a Joplin man named William Simmons arrived to visit her. Simmons was still there on Saturday, December 10, when Mr and Mrs Holly left for a trip to the town of Noel itself. That meant spending the night away, and the Hollys suggested that Simmons might like to accompany them part of the way and then return to Joplin alone. Perhaps they feared what the two young people would get up to if left alone in the house overnight.

Simmons said he'd rather walk as far as Lanagan and then take a train home from there. Mary said she'd stay with him at the Hollys' Mann Farm home until he left, and then cross the Elk River back to her father's house if the water was not too high. If the crossing was impossible, she'd stay on that side of the river with one of the many relatives the Noels had scattered about there.

Judge JA Sturges, who tells this story in his 1897 History of McDonald County, tells us the river's ford was then too flooded for vehicles, but could be negotiated on horseback. “About 8:00 o'clock in the morning Holly and his wife started away, leaving Simmons and Miss Noel together at their house,” he adds. “This was the last ever seen of her alive.” (8)

Instead of returning home on the Sunday, as they'd originally planned, Mr and Mrs Holly stayed at her father's for the next few days. There was no sign of Mary, but everyone assumed she was safe with one of the family's relatives across the river. On the Monday, they began asking around, but could find no trace of her. They sent a letter to one of Mary's uncles in Webb City, about 40 miles away, because they knew she sometimes stayed with him. When he replied that he hadn't seen her, the horrible truth began to dawn.

Instead of returning home on the Sunday, as they'd originally planned, Mr and Mrs Holly stayed at her father's for the next few days. There was no sign of Mary, but everyone assumed she was safe with one of the family's relatives across the river. On the Monday, they began asking around, but could find no trace of her. They sent a letter to one of Mary's uncles in Webb City, about 40 miles away, because they knew she sometimes stayed with him. When he replied that he hadn't seen her, the horrible truth began to dawn.

“Their beautiful daughter and sister was gone,” Sturges says. “No-one knew where, and only those who have experienced the feeling can know the agony which clung to them day and night.”

Mary's father and Mr Holly went to Joplin on the Friday of that week to make enquiries. Holly later testified that he'd seen Simmons there, and confronted him with the words: “Will, your girl's gone”.

“Simmons trembled violently a few seconds and replied ‘Is that so?’” Sturges reports. “He asked no questions concerning her and appeared to be desirous of avoiding the conversation. When asked if she came away with him he replied that she did not. They stood in silence for a few moments, when Simmons remarked: ‘You don't suppose the fool girl jumped in the river and drowned herself, do you?’”

Noel and Holly returned to Pineville and, on the morning of Saturday December 17, began a systematic search. The Noels were a prominent family in McDonald County, and hundreds of volunteers joined the effort, most now assuming that Mary had been deliberately killed. Soon, the search gravitated towards the river, where the deepest stretches were dragged and every spot searched. Here's Sturges again:

“Finally, about 2:00 o'clock in the afternoon, in a narrow, swift place in the river at the lower end of a large, deep hole of water, the body was found where some of the clothing had caught in a willow that projected into the water. It was but little more than quarter of a mile below her father's house and within a few feet of the road along which her parents had passed that fatal Saturday afternoon.

“On examination afterwards, conclusive evidence of a violent death were found. A bruise on one temple, one spot on one cheek and three or four on the other, as though a hand had been placed over her mouth to stifle her screams, finger prints on the throat, were all plainly visible. Beside a bruise the size of the palm of one's hand on the back of her head and her neck broken. The lungs were perfectly dry and all evidences of drowning were absent.”

The searchers also found recent tracks made by a man and a woman between the Hollys' house, where Simmons and Mary had last been seen together, to the river's edge, near the deep area where the body was found. Their conclusion was that the couple must have walked down there together, where Mary planned to use the nearby ford.

Simmons was arrested in Joplin, just as he was getting ready to leave town, but it was feared he'd be lynched if sent back to Pineville, so he went to the jail in Neosho instead. He was tried for first degree murder in May 1893, but the hotly-contested case produced a split jury, and a re-trial had to be arranged. That came in November, when the prosecutor indicated that he'd accept second degree murder, on the grounds that the killing could have been done without the deliberate forethought and intent needed for a first-degree charge. The new jury accepted this, returned a guilty verdict, and Simmons was sentenced to ten years.

In 1927, the folklorist Vance Randolph collected a Knoxville Girl variant from a Mrs Lee Stevens in Missouri. She called this song The Noel Girl, and it begins:

“Twas in the city of Pineville,

I owned a floury mill,

‘Twas in the city of Pineville,

I used to live and dwell.” (9)

The rest of the song canters through the familiar tale, mentioning every important milestone along the way. There's the false promise of marriage, the private walk, the sudden attack, the plea for mercy, the river, the candle, the nosebleed - everything. The Pineville reference and the song's title aside, it's a straightforward reading of Knoxville Girl as everyone came to know it from Arthur Tanner's 1925 recording, with exactly the same details of The Bloody Miller and The Berkshire Tragedy left intact.

It's obviously nonsense to suggest, as some people do, that Mary Noel's death is the prime source for Knoxville Girl. Even so, you can see why her case got drawn in to the song's mythology. The real facts of this killing form an almost uncanny echo of the one described half a world away and 200 years earlier.

Just as in The Berkshire Tragedy, Simmons really did take his unsuspecting victim “from her sister's door”, beat her viciously round the head “and dragged her to the river side then threw her body in”. Holly, encountering the killer in Joplin, may well have asked himself “what makes you shake and tremble so,” just as The Berkshire Tragedy's servant asked of his master. And Mary's body really was found “floating before her father's door”. Sturges tells us Mary was “young (and) extremely handsome”, with “lady like manners”, while The Bloody Miller calls its own victim “a fair and comely maid, thought modest, grave and wise”.

It's almost as though William Simmons arrived at Mann Farm with a copy of The Berkshire Tragedy stuffed into his pocket and set out to re-enact it as closely as he could. There's no suggestion in the 1897 account that he killed Mary because he'd made her pregnant, but it's possible that Judge Sturges avoided this issue for the sake of delicacy. He was writing at a time when Mary's father was still alive, and may have wished to avoid embarrassing one of the county's leading families. Certainly he offers no alternative motive for Simmons' deed.

I've got no proof for this, but I like to think the Mary Noel story's most enduring legacy is to give Knoxville Girl's killer his modern name. Arthur Tanner's 1925 record has the line “Willie dear, don't kill me here / I'm not prepared to die”, and that's the name that's stuck ever since. Tanner's is the earliest version I've been able to find using this name, and I'm content to believe it was the William Simmons case which inspired it. All it would take to scupper this theory is a single pre-1892 version using the name “Willie”, but so far I haven't found one.

In 1917, the song collector Cecil Sharp visited Kentucky, where he persuaded two women named Wilson and Townsley to sing a song which they called The Oxford Tragedy. What emerged was a “missing link” between the British and American versions of the song, taking its title from England but setting its tale in America. Once again, the protagonist is a miller, but this time he tells us:

In 1917, the song collector Cecil Sharp visited Kentucky, where he persuaded two women named Wilson and Townsley to sing a song which they called The Oxford Tragedy. What emerged was a “missing link” between the British and American versions of the song, taking its title from England but setting its tale in America. Once again, the protagonist is a miller, but this time he tells us:

“I fell in love with a Knoxville girl,

Her name was Flora Dean”. (10)

When Flora's body is later found, it's:

“A-floating down by her father's house,

Who lives in Knoxville town.”

Eight years later, with Tanner's record, Knoxville became the accepted setting for this tale, and all the other locations sank to footnote status. Once a song's been committed to disc and widely heard on the radio, that rapidly becomes the official version, and any deviations from its line are seen not merely as variations, but mistakes.

Tanner's record might never have reached the market at all if it hadn't been for an earlier 1925 hit by Vernon Dalhart called The Death of Floyd Collins. This told the tale of a young man who got himself trapped in Kentucky's Sand Cave in February 1925, and whose plight was avidly followed by newspaper readers and radio listeners throughout America. Collins eventually died of starvation and exposure, and Columbia scored a bit hit with the Dalhart record that followed in May. (11)

Henry Sapoznik, writing in the sleeve notes for Tompkins Square's People Take Warning compilation, say's Dalhart's record “set in motion a rage for country-tinged exploitation event songs which made 78s and sheet music the broadside ballads of the post-industrial age”. Looking for more of the same, Columbia had Tanner re-record the same version of Knoxville Girl which they'd scrapped from his earlier session, and that was when the song took off. (11, 12)

By the time The Louvin Brothers started their radio career around 1941, Charlie recently recalled, Knoxville Girl was the most popular song in their repertoire. “Knoxville Girl was the most requested song that Ira and I would ever sing,” he told Smoke Music Archive's Nathan Salsburg. “We found out that people liked the song, and if we didn't do it, somebody in the audience would get mad, so we started including it always.” (13)

Charlie uses the same interview to set out his view of why the song's victim had to die. For him, it's her “dark and roving eye” that provides the explanation. “There's still these idiots out there that will say ‘If I can't have you, then nobody can’,” he says. “That causes a bunch of murders in this country, simply because this guy's in love with her, and she's not in love with him. She likes him as a friend, but not to marry, so he comes up with this great plan.”

As we've seen here, the song's history produces a different conclusion. But if you consider the lyrics to Knoxville Girl alone, then Charlie's explanation makes perfect sense. Besides, who am I to argue with the song's finest living interpreter?

For all its debt to the old English ballads, there's no doubt that Knoxville Girl is a better song than any of its predecessors. It's much sharper and more concise than the English originals, for example, and gains all the more punch from that. The 12 verses of Knoxville Girl in its classic form are far easier for a singer to memorise than the 44 verses he'd have to contend with in The Berkshire Tragedy's original text, and present far less a challenge to the modern audience's patience.

Where the flavour of the English songs is one of cheerful tabloid vulgarity, Knoxville Girl replaces this with a stoic fatalism that quietly acknowledges the Devil lurks inside us all. The line describing Knoxville as “a town we all know well”, suggests the song is an intimate confession to the singer's close neighbours, and that's a feeling missing from the earlier versions too. If he prefers not to spell out his tale's sexual content in graphic detail, then that just hints at a thwarted small-town decency which makes it all the more heartbreaking.

Death was an everyday reality for the subsistence farmers who first brought Knoxville Girl to America's southern states, and their harsh Calvinist religion offered no illusions about the rewards sin would bring. The few pleasures they could hope for – rutting, moonshine and fiddle tunes – seemed only to promise eternal damnation.

“The people of the South were ‘God-fearing’ in the strictest sense of the word,” says Ben Austin in his Introduction to the Folk Background. “The dangers of immoral behaviour inherant in religious fundamentalism, coupled with the harsh realities of frontier life, produced an ambivalence towards sexuality, alcohol and music. [...] Confronted with the hardships of the frontier, these people dealt with their lonliness and frequent defeat and despair through an other-worldly religion and through the folk songs, ballads and hymns which they brought from Britain.” (14)

The folk tradition has written these qualities into every note of Knoxville Girl and it's that which accounts for its extraordinary power.

For testimony of that power, let's return to Ruth Gerson. The New York Times recently called her “as galvanic as Bruce Springsteen”, she's sung on American network TV's Conan O'Brien Show, and includes Knoxville Girl on her 2011 album Deceived. I e-mailed Gerson via her website to ask what the song meant to her.

“Deceived is a collection of songs about the bad things that happen to ‘bad girls’,” she replied. “Knoxville Girl was one of the first songs that inspired the album. The first time I heard it was a Nick Cave version, then I listened to The Louvin Brothers – and threw up from being so disturbed.

“We think the murder of those weaker and unable to defend themselves is wrong, but we do not scream out against it: we sing and dance to it. Knoxville Girl is an incredible song, but it shakes me down every time I sing it.”

Appendix I: Loved so well: Ten Knoxville knockouts

Knoxville Girl, by Arthur Tanner & His Corn Shuckers (1927). The first commercial recording, and the one which set the lyrics in stone for everyone that's followed. Tanner's vocals are surprisingly clear for such an old record, and the fiddle and guitar accompaniment keeps everything moving along nicely. Available on: Paramount Old-time Recordings (JSP, 2006).

Knoxville Girl, by The Louvin Brothers (1956). Bearing a clear influence from The Blue Sky Boys' 1938 version, The Louvins add a shuffling beat and produce the song's single most essential version. The Everly Brothers idolised Charlie and Ira Louvin, and this record tells you why. Available on: Tragic Songs of Life (Righteous, 2009).

Knoxville Girl, by Charlie Feathers (1973). The former Sun Studios session musician and self-styled “King of Rockabilly” brings a touch of Elvis to this hillbilly rap version. There's a stop/start beat, a knowing melodrama to his spoken-word vocals and some enjoyably twangy guitar. It should be a mess, but actually it works rather well. Available on: Long Time Ago Vol 1 (Norton, 2008).

Knoxville Girl, by Kevin Williams & Friends (1997). Each musician takes the lead for a verse or two in this rather lovely instrumental version. Williams' mandolin and Craig Duncan's hammered dulcimer describe the slaughter, while Glen Duncan's fiddle is left to mourn the results. Available on Smoky Mountain Memories: Songs of Tennessee (Green Hills, 1997).

Knoxville Girl, by Mark Jungers (2002). A busy acoustic guitar lurches us into this flat-out rockabilly treatment. Jungers and his band take the course at 90 MPH, conjuring up a picture of sweaty quiffs, heavily-tattooed arms and a drummer who stands up to play. Splendid stuff. Available on: Standing in Your Way (American Rural, 2002).

The Oxford Girl, by Waterson:Carthy (2004). That's Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy, of course, who give us this rare recording of Knoxville Girl's ancestor. Tim van Eyken's melodeon sets an appropriately mournful tone as Norma sings her way to the gallows. Available on: Fishes & Fine Yellow Sand (Topic, 2004).

Knoxville Girl (Parting Gift), by Jennie Stearns (2005). Not a version of the original song, but Stearns' meditation on the Knoxville Girl's fate and the baffling cruelty of men. The gift, it turns out, is Stearns' song itself, placed like a gentle flower on the victim's grave. It's every bit as sweet as it sounds. Available on: Sing Desire (Blue Corn, 2005).

Knoxville Girl, by Sheila Kay Adams (2005). Sheila learned this song as a child in the evocatively-named town of Sodom, North Carolina, and her a cappella version is one of the loveliest I've heard. Clear, steady and tuneful, it's a little gem. Available on: Song Links 2 (Fellside, 2005).

Knoxville Girl, by Charlie Louvin & Will Oldham (2007). Young bands often revel in the brutality of Knoxville Girl, but Louvin's sombre solo reading is a chastening reminder of what violence really means. Make way for a grown-up, children. Available on: Charlie Louvin (Tompkins Square, 2007).

Knoxville Girl, by Rachel Brooke (2008). Brooke coats this recording with surface noise to mimic the 78s she so obviously loves, which creates a pleasing old-time feel. She gives a clever twist to the lyrics too, turning the story into one about a girl murdering the woman her true love prefers. “I murdered that Knoxville Girl,” she boasts at the end. “That girl he loved so well”. Available on: Rachel Brooke (Rachel Brooke, 2008).

Appendix II: Banks of the Ohio: KG's distant cousin?

There's no mention of the crucial nosebleed in this 1971 Olivia Newton John hit, but its resemblance to Knoxville Girl's plot is still striking.

A couple go for a private walk by the river, one of them produces a knife and ignores the other's protest about being unprepared for eternity. After the stabbing, the victim's body is dragged into the river and the killer returns home protesting true love.

But there are differences too. This time, it's the murderer who wants to get married, and the victim who refuses. When the knife appears, the victim seems almost eager to die, pushing on to the blade as it pierces flesh.

The fact that this song's so often sung by a woman produces some twists too. Newton John casts herself as the murderess (“I killed the only man I love / He would not take me for his bride”), but Kristen Hersh plays the victim (“He drew his knife across my breast / And in his arms I gently pressed”).

Snakefarm's Anna Domino seems to be singing as a male killer (“I asked your mother for you dear / And she said you were too young”), but the more I listen to her carefully ambiguous lyrics, the less certain I am. Couldn't that “lily hand” she mentions equally belong to a young man killed by a besotted older woman?

Olivia Newton John took her version of Banks to number 6 in the UK charts back in 1971, and it stayed in the top 50 here for 17 weeks. This remains Knoxville Girl's closest claim to major chart success, and one which later Banks covers by Johnny Cash, The Handsome Family and Otis Clay have been unable to match.

Song scholars trace Banks back to an older song with an identical plot called The Banks of the Old Pee Dee, first collected in 1915. The best-known river of that name originates in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina, a region where we know Knoxville Girl's source songs had been adapted for American use since the early 1800s. Somewhere along the way, Banks discarded its telltale nosebleed, but the family resemblance remains unmistakable.

Appendix III: Staking my claim to 1683's parish register nugget

I first researched Knoxville Girl back in early 2005, when I was hoping to sell BBC Radio 4 the idea of a series about murder ballads.

In June of that year, it occurred to me that I should check the burial records for Hogstow in Shropshire to see if there was any trace of a Francis Cooper or an Anne Nichols being interred there in 1684.

I worked out that the closest surviving church was the Holy Trinity in Minsterley, told Alan Toop, the vicar there, about The Bloody Miller, and asked him if he had any churchyard records going back that far.

Reverend Toop said any records from that era would be stored at the Shropshire Archive, so I e-mailed them with all the details I had and sat back to await results. On June 30, 2005, I got a reply from the Archives' Jean Evans saying:

“I have searched the transcript of the Westbury Register for 1683 and found an entry for the burial of Anne Nicholas, murdered (truculenter occisa – ie a violent death), and then later a baptism of a child, Ichabod, son of Francis Cooper, homicide, and Anne.

“There is no entry for a burial of Francis Cooper, and the child baptised would be the child of Francis and Anne Cooper.”

Jean sent me the documents she'd consulted a few days later, enclosing a photocopy of both the Westbury Parish Register's hand-written original and a printed transcript. These showed that Anne had been buried on March 1, 1683, and Ichabod baptised on March 24.

The lack of a burial record for Francis Cooper was disappointing, but I'd half-assumed the church would have refused to bury an executed murderer on holy ground anyway.

I was delighted. Here was documentary proof that there really had been a Shropshire murderer called Francis Cooper at the time Philip Henry made his February 1683 diary entry. Not only that, but we also had a murder victim called Anne Nicholas - a very close match to the Anne Nichols mentioned in Pepys' Ballads - and evidence that they'd had a child together.

Whoever named that child Ichabod knew what they were doing too. The name means “no glory”, and comes from the First Book Of Samuel, where the wife of Phinehas delivers a son just after hearing its father has been killed in battle and her people defeated. She calls the child Ichabod to reflect the grim circumstances of its birth, and then promptly dies herself.

I still couldn't explain how the Westbury Ichabod had come to be born when the ballad insisted his mother had died in pregnancy, nor the parish register's implication that Francis and Anne were married after all. But the rest of the facts fitted quite well enough to establish that they were definitely the same people described in The Bloody Miller's introduction, and that was no small beer.

What's more, I seemed to be the first person who'd ever dug this information out of the archive. I gave myself a little pat on the back, slipped the copies into a file and thought what a cracking revelation they would make for Radio 4's Knoxville Girl episode.

Meanwhile, Rev. Toop, still trying to help with my original query, had contacted a local historian called Peter Francis, who later posted on The Mudcat Café folk music forum.

His post, which appeared on July 25, 2005, confessed that he'd only just come across The Bloody Miller story, asked Mudcat readers for any more details they could provide, and added that he'd been unable to find anything in the Shropshire Archive. At that point, I was still hoping Radio 4 might buy the murder ballads idea, so I was saving my own findings for that.

On November 2, 2005, Peter Francis posted on Mudcat again, this time with exactly the same information I'd uncovered four months earlier. He also wrote it up for his local church magazine, adding some baptism entries he'd discovered, which indicated Francis was 27 when the murder happened and Anne was 23.

Radio 4 never did buy the murder ballads idea, so I was left kicking myself for failing to claim my find while I had the chance. Peter Francis found the information independently, though, so I really can't complain. It may have been my call to Rev. Toop which first set him on the trail, but everything else came through his own efforts.

I've since visited the parish church in Westbury, Shropshire, where genealogist friends assure me Anne Nicholas would almost certainly have been buried. The churchyard there has no surviving gravestones older than about 1800, but it's still nice to know the general area where she was laid to rest. You'll a find a photo elsewhere in this article.

I may seem to be belabouring all this, but those names in the Westbury Parish Register are probably the only bit of genuine original scholarship I'll ever get to contribute to the study of a major folk ballad like Knoxville Girl. With that in mind, I'm going to claim a modest first for myself in digging them out, and the date I'm pinning my flag to is June 30, 2005. So there.

Sources

(1) Knoxville Girl, by The Louvin Brothers (Capitol 1956).

(2) Diaries & Letters of Philip Henry 1631-1696, by Philip Henry (Trench & Co, 1882).

(3) The Pepys Ballads Vol III, ed. Hyder Edward Rollins (Harvard University Press, 1930).

(4) American Balladry from British Broadsides, by GM Laws (University of Texas Press, 1957).

(5) J Pitts Collection of Ballads & Songsheets, University of Minnesota Libraries (http://mh.cla.umn.edu/pitts.html).

(6) A Dictionary of Superstitions, ed. Iona Opie & Moira Tatum (Oxford University Press, 1989).

(7) The Cassell Dictionary of Folklore, ed. David Pickering (Cassell, 1999).

(8) History of McDonald County, Missouri, by Judge JA Sturges, published 1897.(http://www.archive.org/details/illustratedhisto00stur)

(9) Ozark Folksongs Vol IV, ed. Vance Randolph (University of Missouri Press, 1980).

(10) English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, ed. Cecil Sharp & Maud Karpeles (Oxford University Press, 1960).

(11) Root Hog Or Die (http://roothogordie.wordpress.com/2008/09/09/on-murder-ballads/).

(12) People Take Warning: Murder Ballads & Disaster Songs 1913-1938, by Various Artists (Tompkins Square Records, 2007).

(13) Smoke Music Archive (http://www.smokemusic.tv/content/sing-murder).

(14) Introduction to the Folk Background, by Ben S. Austin (http://frank.mtsu.edu/~baustin/britfolk.html).