"NEGRO SHOT BY WOMAN

"NEGRO SHOT BY WOMAN

Allen Britt, colored, was shot and badly wounded shortly after 2 o'clock yesterday morning by Frankie Baker, also colored. The shooting occurred in Britt's room at 212 Targee Street, and was the culmination of a quarrel. The woman claimed that Britt had been paying attentions to another woman. The bullet entered Britt's abdomen, penetrating the intestines. The woman escaped after the shooting."

- St Louis Globe-Democrat, October 16, 1899.

Just 48 hours after Frankie Baker pulled that trigger, a ballad telling her story was already being sold on the city's street corners. Allen wasn't even dead yet - he didn't finally succumb to his wounds until October 19 - but already the balladeers had him six feet under. The song's been in constant circulation ever since.

The fact that Allen's murder took place just a few blocks from where Stagger Lee had killed Billy Lyons four years before means the two ballads have always tended to get tangled up with one another, swapping fragments of their lyrics at will. It's no surprise that many of Frankie's musical biographers - Bob Dylan, Elvis Presley, Mississippi John Hurt - have tackled Stag's story too, but what is unique about her is the degree of interest that Hollywood's always shown.

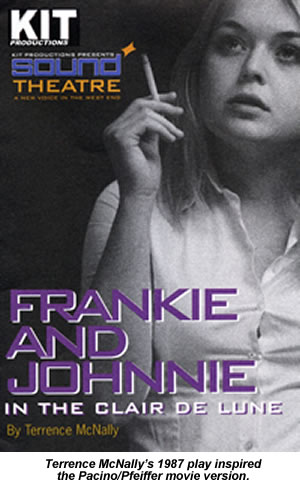

From Mae West's 1933 outing She Done Him Wrong to the 1991 vehicle for Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer, Frankie has seldom been off the silver screen. She's trod the theatre's boards pretty regularly too, appearing in both John Huston's 1930 play about her crime and Terrence McNally's Frankie & Johnny in the Clair de Lune, which was given a London production as recently as 2005. As we'll see, very few of these productions have bothered themselves much with the facts, but they have ensured that the two lovers' names remains firmly linked together in all our minds.

Frankie Baker was a young prostitute, aged about 24 when the killing took place, who lived and worked at 212 Targee Street in the heart of St Louis' flourishing vice district. Richard Clay, a former neighbour, described her like this: "She was a beautiful, light brown girl, who liked to make money and spend it. She dressed very richly, sat for company in magenta lady's cloth, diamonds as big as hen's eggs in her ears. There was a long razor scar down the side of her face she got in her teens from a girl who was jealous of her. She only weighed about 115lbs, but she had the eye of one you couldn't monkey with. She was a queen sport."

Allen Britt, who was about 17 when he died, shared Frankie's Targee Street rooms, and seems to have acted as her pimp. He was a talented piano player and known as a snappy dresser. He was also cheating on Frankie with an 18-year-old prostitute called Alice Pryar.

The film director John Huston, then a struggling writer, interviewed Clay for a footnote essay to his play, the text of which was published in 1930. "Frankie loved Albert all right," Clay recalled. "He was wise for his years but not old enough to be level with any woman. Frankie was ready money. She bought him everything he wanted, and kept his pockets full. Then while she was waiting on company he would be out playing around."

Clay, who had sat with Allen while he died in City Hospital, also gave Huston his own account of what had happened on the fatal night. He said Frankie had surprised Allen with Alice at the Phoenix Hotel, calling him out into the street for a furious public row. Allen, Clay said, had refused to go home with Frankie, so she'd returned to Targee Street alone. Allen turned up there about dawn, admitted he'd spent the night with Alice, and threatened to leave Frankie for good. According to Clay, Frankie had then started crying and started out the door to find Alice. Allen threatened to kill her if she took another step, and that's when the fight broke out(1).

Frankie gave her own version of events when interviewed by Daring Detective Tabloid in 1935. She said she had known Allen was at a party with Alice on the Saturday night, but refused to let that bother her. She went home and went to bed. "About three o'clock Sunday morning, Allen came in," she said. "I was in the front room, in bed asleep, and he walked in and grabbed the lamp and started to throw it at me. [...] I asked him, 'Say, are you trying to get me hurt?', and he stood there and cursed and I says, 'I am boss here, I pay rent and I have to protect myself.' He ran his hand in his pocket, opened his knife and started around this side to cut me. I was staying here, pillow lays this way, just run my hand under the pillow and shot him. Didn't shoot but once, standing by the bed." Frankie also claimed Allen had beaten her badly a few nights before the killing(2).

Allowing for the assumption that both Frankie and Allen were trying to salvage what pride they could when relating the incident, there's no real contradiction in these two accounts. Allen - via Clay - tells us what happened up to the point when Frankie went home, and Frankie takes up the story from there.

Allen staggered from the room when Frankie shot him, and made it as far as the steps of his mother's house at 32 Targee Street before collapsing. He told her what had happened, and - according to Clay - she began to scream "Frankie's shot Allen! Frankie's shot Allen!" By the time he'd been taken to City Hospital, everyone in the neighbourhood knew that Frankie had got her man.

Police took Frankie to the hospital too, where Allen confirmed she was the one who'd shot him. He died four days later. Frankie was arrested, and went to trial on November 13, 1899, where the jury found for justifiable homicide in self-defence. "I ain't superstitious no more," she later said. "I went to trial on Friday the 13th, and the bad luck omens didn't go against me. Why, the judge even gave me back my gun."

By Christmas of that year, Frankie had already started to hear "her" ballad sung on the streets. Ballad sellers would pick up on the most lurid news stories of the time, turn them quickly into verse and sell the resulting single-sheet copies at 10c a time on street corners. Often, they would stir up interest by singing the songs themselves to attract a crowd. Frankie Killed Allen, the first song to tell this particular story, was composed by Bill Dooley, one of St Louis' most prolific balladeers. By the evening after the shooting, it was already being performed and sold(3).

By Christmas of that year, Frankie had already started to hear "her" ballad sung on the streets. Ballad sellers would pick up on the most lurid news stories of the time, turn them quickly into verse and sell the resulting single-sheet copies at 10c a time on street corners. Often, they would stir up interest by singing the songs themselves to attract a crowd. Frankie Killed Allen, the first song to tell this particular story, was composed by Bill Dooley, one of St Louis' most prolific balladeers. By the evening after the shooting, it was already being performed and sold(3).

The first sheet music version was published in 1904 by Hughie Cannon, a black-face comedian who turned the song into a sequel to his earlier hit Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home. Cannon kept Dooley's tune and refrain "He done me wrong", but threw out everything else. By 1909, when the song collector John Lomax found a Texas version, Allen (or Al) Britt had become Albert. He was rechristened again in Frank & Bert Leighton's 1912 sheet music for their vaudeville song Frankie & Johnny, a name which has stuck ever since. A similar process turned Alice into "Nellie Bly", a name which singers may have found easier to remember and pronounce. The first version of the song recorded seems to be the Paul Biese Trio's jaunty 1921 reading.(4)

Huston's 1930 melodrama sticks closely to the ballad's plot, carefully including the $100 suit of clothes which Frankie buys for Johnny, their vow to remain as faithful as the stars and Johnny's dalliance with Nellie Bly. Frankie kills Johnny with the traditional three shots, giving him time to quote a verse from the ballad verbatim before he dies, and then goes uncomplaining to the gallows. Huston leaves the audience to decide exactly how Frankie's earned the money Johnny steals from her, but does nothing to deny that she's a prostitute.

Huston ensures that everyone speaks in heavy Yosemite Sam accents throughout ("I was a-goin' to turn it over to ye in one lump sum a cash like ye allus wanted") and canters through the whole tale in a brisk 60 pages of double-spaced dialogue. He saves his most macabre touch for the end, when Frankie addresses the crowd gathered round her gallows and offers to lead them all in one final dance. "I'll be showin' ye new steps in a minute," she promises as the hangman places the noose around her neck. "Steps ye've never seen before."

Just as with Stagger Lee, Frankie's tale also produced an underground "toast" version of the song, far too filthy to be published in any respectable journal or recorded commercially. Fortunately, the anonymous compiler of a privately-published 1927 anthology called "Immortalia" liked Frankie & Johnnie enough to include it in his daringly raunchy book. The 18 verses tell the same core story, but offer a far less squeamish account of what its two protagonists' lives must really have been like.

Frankie, we're told, is a "fucky hussy", who's whoring keeps her so busy that she "never had time to get out of bed". She gives all her money to Johnnie, "who spent it on parlor house whores", but still can't stop him "finger-frigging Alice Bly". She shoots Johnnie five times rather than the traditional three, and later boasts in court "I shot him in his big fat ass".

I've never heard a recorded version of these lyrics, but here's a couple of sample verses to give you the flavour. The first comes as Frankie takes a break from awaiting company - as Clay would have put it - to hand over the cash she's earned:

"Frankie hung a sign on her door,

'No more fish for sale',

Then she went looking for Johnnie,

To give him all her kale,

He was a-doin' her wrong,

God-damn his soul!"

And here's what happens when Frankie discovers the awful truth:

"Frankie ran back to the crib-joint,

Took the oilcloth off the bed,

Took out a bindle of coke,

And snuffed it right up in her head,

God-damn his soul,

He was a-doin' her wrong!" (5)

There's several variations on these lyrics, which add additional refinements such as Frankie shooting Johnnie in the balls or firing a bullet directly up his hole. In one version, she brings his penis back from the graveyard as a souvenir, explaining that it's "the best part of the man who done her wrong".

Brutal as these versions are, they may well be closer to the truth. We know from contemporary press reports that cocaine was a popular drug in 1890s brothels, so it makes sense to imagine Frankie using the stuff. Street-level prostitution in any age is likely to be a fairly squalid and violent affair, so it's hard to accuse the toast of being unduly lurid on those grounds. It certainly isn't pretty, but then Frankie's real life must often have lacked decorum too.

The real Frankie soon started to tire of her new notoriety, and left St Louis in 1900. She moved first to Nebraska and then to Oregon, but found the song followed her everywhere she went. After a few years working as a prostitute in Portland and several arrests, she opened a shoeshine parlour there around 1925. The ballad never quite went away - Mississippi John Hurt, Riley Puckett and Jimmie Rodgers all recorded it between 1928 and 1932 - and the first film adaptation came out in 1930, but for a while she was left in peace. In 1933, all that changed.

Paramount Pictures' She Done Him Wrong was Mae West's first starring vehicle, and also the film which kick-started Cary Grant's career. Based on West's play Diamond Lil, it contains many of her best lines, as well as West's own rendition of Frankie & Johnny. When the film reached Portland, Frankie found strangers gathering outside her home to point at her and stare. "I'm so tired of it all, I don't even answer any more," she told a reporter. "What I want is peace - an opportunity to live like a normal human being. I know that I'm black but, even so, I have my rights. If people had left me alone, I'd have forgotten this thing a long time ago."

Frankie sued Paramount, claiming the song's account of her life was defamatory, and full of factual errors. The shooting had happened at home, she said, not in a saloon as the song often claimed. Allen was a "conceited piano player" not a gambler, and her gun had been not a .44 but a .38, which she fired only once, not the three times stated in the song. Asked whether she had ever bought Allen a $100 suit of clothes - another "fact" given in the ballad - Frankie replied "not necessarily". Despite these discrepancies, the jury was not convinced Frankie deserved any compensation, and she lost her case.(6)

Frankie sued Paramount, claiming the song's account of her life was defamatory, and full of factual errors. The shooting had happened at home, she said, not in a saloon as the song often claimed. Allen was a "conceited piano player" not a gambler, and her gun had been not a .44 but a .38, which she fired only once, not the three times stated in the song. Asked whether she had ever bought Allen a $100 suit of clothes - another "fact" given in the ballad - Frankie replied "not necessarily". Despite these discrepancies, the jury was not convinced Frankie deserved any compensation, and she lost her case.(6)

She sued again over Republic's 1936 film Frankie & Johnny, which starred Helen Morgan in a loose adaptation of the song's story. Frankie argued that the new film presented a false and humiliating account of her life and asked for $200,000 in damages. This time, the studio hired the musicologist Sigmund Spaeth as an expert witness. Spaeth, who was paid $2,000 for his testimony, reversed the conclusions of his own 1927 book to argue that the ballad Frankie & Johnny pre-dated 1899, and therefore that it could not have been based on Frankie Baker's crime. Until then, Spaeth had always maintained that Frankie was the ballad's inspiration, but that's not what he said in court. Once again, Frankie lost.(3)

Spaeth's testimony is infuriating, but Frankie's chances of victory had always been pretty slim. Watching the two films now, it's hard to see how she ever hoped to build a case.

Frankie - or in Mae West's case, her stand-in Lady Lou - is presented as a sympathetic character in both films, and never actually kills anyone herself. The worst you can say of Lou is that she knowingly sends a man off to his death, but he's such a revolting character that we're encouraged to think it served him right. The Helen Morgan vehicle sticks closer to real story, but makes Frankie a saintly figure who's saved from pulling the fatal trigger by another character stepping in first.

The truth of the matter is that the damage Frankie suffered from these two films lay less in the plots they used than in the fact that they pulled the song back to the front of everybody's mind and made it even more famous than it had been before. We know that She Done Him Wrong was a huge hit, pulling in $2.2 million on Paramount's investment of just $200,000, and that sort of box-office take in 1933 translated to a vast audience. That's what generated the sudden surge in curiosity about her which Frankie found so distressing, but it wasn't a close enough connection to win her case.

In 1950 or 1951, Frankie was admitted to a mental hospital, aged about 75. She was still perfectly lucid about killing Allen, but seemed confused about every other aspect of her life. In January 1952, she died.

The real Frankie may be dead, but her fictional alter-ego seems as immortal as ever. A 1962 thesis by Bruce Redfern Buckley found no fewer than 291 versions of Frankie's ballad to study. Since then, we've had two more Frankie & Johnny movies, one starring Elvis Presley in 1966 and one starring Al Pacino and Michelle Pfeiffer in 1991. As we'll see in a moment, neither bore any notable resemblance to the facts.

Songwriters have not been shy to apply artistic licence either. Sam Cooke's 1963 version of Frankie & Johnny - a top 30 hit on both sides of the Atlantic - had Frankie giving her beau a sports car and some "Ivy League clothes". Bob Dylan included the song on his 1992 album Good As I Been To You, but could not resist adding details of Frankie's execution on the gallows. Jimmie Rodgers sent her to the electric chair. Jimmy Anderson's 1969 blues version for Excello ended with Frankie getting drunk in the bar where she'd found Johnny, and then merely dumping him instead of killing him.

It's far from the only measure of a song's success, of course, but if it's accuracy you're after, then Mississippi John Hurt's 1928 Frankie is hard to beat. Recorded relatively close to the event that inspired it, this version gets just about everything right.

"Frankie called Albert,

Albert says 'I don't hear',

'If you don't come to the woman you love,

I'm gonna haul you out of here',

You's my man,

And you done me wrong."

"Frankie shot ol' Albert,

And she shot him three or four times,

Says: 'Stroll back, I'm smokin' my gun,

Let me see, is Albert dyin'?

He's my man,

And he done me wrong'.

"Frankie and the judge walked down the stairs,

They walked out side by side.

The judge says to Frankie,

'You're gonna be justified,

For killin' a man,

And he done you wrong'." (7)

All the characters are given their real names, the row in the street which Clay describes is sketched out, and Frankie leaves the court a free woman. True, Hurt has Frankie shoot Albert three or four times, and sends her along to a funeral she never attended, but compared to the liberties taken in other versions, these are very small offences. Everyone else may have done Frankie wrong, but Hurt is an honourable exception.

Appendix I: Ten versions you must hear

Leaving Home, by Charlie Poole & The North Carolina Ramblers (1926). Poole's retitled version of Frankie & Johnny gives the song a jolly hillbilly treatment, courtesy of Ramblers' fiddler Posey Rorer. Poole makes Frankie the villain of the piece. She shoots Johnny in the back for threatening to leave her and then begs to be jailed afterwards. Available on: Charlie Poole with the North Carolina Ramblers and the Highlanders (JSP, 2004).

Frankie, by Mississippi John Hurt (1928). As with his reading of Stagger Lee - based on another St Louis murder of the 1890s - Hurt gives his subject all due gravitas. The gentle beauty of his guitar picking is never allowed to disguise what a sad and wasteful episode he is describing. Far from glorifying the sensational aspects of murder, Hurt's version is full of human sympathy. Available on Candy Man Blues (Complete Blues, 2004).

Frankie & Albert, by Leadbelly (1934). Recorded at Angola prison by John and Alan Lomax, Leadbelly gives us a half-sung, half-spoken version set to the steady strum of his own guitar. Frankie's a cook in the white folks' kitchen here, and Alice Pryar is given her real name. Albert's mother gets a walk-on part too, as Frankie apologises for killing the woman's only son. Available on: Best of Leadbelly (X5 Music, 2008).

Frankie & Johnny, by Sammy Davis Jr (1956). Notable not only for the determined use of jazz lingo ("He was her mate / But he couldn't fly straight"), but also for Cyd Charisse's stunningly sultry dancing. The 1956 MGM musical Meet Me In Las Vegas has Sammy singing the story while Cyd slinks through Frankie's role in a big production number which is sexy, witty and inventive. She's never been more of a "queen sport" than this. Available on: The Decca Years (MCA, 1990).

Frankie's Man Johnny, by Johnny Cash (1958). Cash casts Johnny as a touring guitarist who leaves his faithful woman at home to have some fun on the road - just as Cash himself was doing at the time. Powered along by the Tennessee Two's trademark chug, Johnny tries to seduce a redhead at one of his gigs only to discover it's his girl's sister checking up on him. It's a near-miss but he's Frankie's man and "he still ain't done her wrong". Available on Cash: The Legend (Sony. 2005).

Frankie & Johnny, by Sam Cooke (1963). Blasting horns and a smoldering bassline help Cooke nudge the song towards the era's popular teen death anthems. Johnny's updated sports car and ivy league clothes can't save him from Frankie's assumptions of infidelity, but he dies protesting his love for her anyway. Available on Sam Cooke Hits (RCA, 2000).

Frankie & Johnny, by Elvis Presley (1966). Presley sings the song from Johnny's point of view, confessing to his dalliance with Nellie Bly, getting shot by Frankie and telling us all about it from beyond the grave. This version outdid Sam Cooke's chart success with Frankie, reaching number 21 in the UK against Cooke's number 30. The dance number which accompanies this song in Presley's movie of the same name isn't a patch on Cyd Charisse's version, however. Available on: Frankie & Johnny OST (Sony BMG, 1994).

The New Frankie & Johnny, by The Innsiders (1983). Not a great version, perhaps, but worth hearing all the same. This finger-clicking barbershop quartet transplant the story to New York and replace Nellie Bly with Edgar Allan Poe's Annabel Lee. Imagine Homer Simpson's Be Sharps covering the song, and you won't be far out. Available on: The Way We Were (Naked Voice, 2007).

Frankie & Johnny, by Snakefarm (1999). Singer Anna Domino takes it slow for this brooding, bluesy version of the tale. Frankie's love and pride in Johnny is evident in Domino's delivery, but so is a quiet, slow-burning anger. Unlike many other takes on the song, this one takes care to relish Johnny's slow death. Available on: Songs From My Funeral (BMG, 1999).

Frankie, by Beth Orton (1999). Recorded live at Nick Cave's Meltdown festival in London, Orton accompanies herself on acoustic guitar in a fragile, keening rendition that's clearly determined to do Frankie justice. Slipping into the killer's skin for her final verse, Orton concludes the song with a chilling first-person narration. Available on: The Harry Smith Project (Sony BMG, 2006).

Appendix II: Frankie on screen

1930: HER MAN, STARRING HELEN TWELVETREES (PATHE)

I've never seen this early talkie, but I know it involves a barmaid who falls in love with a sailor. Allmovie.com notes that it was based on a "naughty" stage play called Frankie & Johnny, which may be a reference to Huston's opus. Promotion for the film called it "the blood-firing romance of a girl WHO DARED THE WORLD FOR LOVE!" The Radio Times' film guide is less impressed, saying it's an "unconvincing, weary waterfront melodrama" with "little to recommend it".

1933: SHE DONE HIM WRONG, STARRING MAE WEST (REPUBLIC)

The closest thing to a character portraying Frankie in this Mae West vehicle is West's Lady Lou, a saloon singer working on the New York Bowery in the 1890s. Lou's old boy friend Chick Clark has been jailed and she's hooked up with Gus Jordan, the saloon's owner instead.

What she doesn't know is that Gus runs a counterfeiting operation and helps the sinister Russian Rita with what seems to be a white slavery scheme. Then there's Dan Flynn, a police informant who hopes to steal Lou away from Gus by shopping him to Cary Grant's Captain Cummings (aka The Hawk), a fearless Federal agent who's working undercover at the saloon as a Salvation Army captain.

When Rita's lover Serge falls for Lou, Rita gets jealous and attacks Lou with a knife, only to stumble on to it herself and die. Meanwhile, Chick escapes from jail, threatens Lou, and then hides in her room. Lou sees him sneak in there as she's singing Frankie & Johnny from the saloon stage, and signals the watching Dan to go and wait for her there. Dan slips out of the audience hoping for an assignation with her, but surprises Chick instead, who promptly kills him.

The gunshots spark a police raid, during which The Hawk arrests both Chick and Gus, sending them off to jail. We think he's going to arrest Lou too, but instead he whisks her into a separate carriage where the two kiss and head off for a life of married bliss.

The links to Frankie's real story are limited to the film's title - which simply flips gender to reflect its female star - the version of the song we hear Lou sing on stage - which stops short of describing the actual murder - and the odd self-aware line. "Some guy done her wrong," Lou says at one point. "The story's so old it should have been set to music long ago."

1936: FRANKIE & JOHNNY, STARRING HELEN MORGAN (REPUBLIC)

Helen Morgan's 1936 version sticks much closer to the real story although, once again, its stars are all white. Morgan plays Frankie, a St Louis saloon singer of the riverboat era who's never given a surname. Saloon singers were presumably the closest movies of the day dared come to making a prostitute their main character.

Frankie falls for Johnny Drew, a riverboat gambler who's new in town. She ditches her plans to marry the faithful Curly and gets set to wed Johnny instead. Seeing their happiness, the evil Nellie Bly threatens to scar Frankie's face with a lethal-looking hatpin, but is dragged away before she can act.

Frankie and Johnny marry, but Johnny loses all their money at the tables. She tries to help him, but Johnny just hears that as nagging, and decides he needs a fresh start in New Orleans. He announces he's going to leave on The Natchez' midnight sailing, and promises to send for Frankie as soon as he's built up a stake there. They can't afford two tickets right now, he claims.

Frankie arranges to borrow $1,000 from her friend Lou so she can go to New Orleans with Johnny straight away, but he intercepts the money, and runs to Nellie instead. He can't face staying with Frankie, he tells her. "I'm not a bad guy, Nellie," Johnny insists. "I'm just not the kind Frankie thinks I am." Nellie agrees to go with him.

Curly can see there's dirty work afoot, so he warns Johnny that if he ever hurts Frankie, there'll be trouble. He then tells Frankie that he's seen Johnny heading for Nellie's place, and she heads off after him with a gun. The ending's left deliberately ambiguous, but the one thing we can be sure of is that it's not Frankie who finally pulls the trigger. Johnny gets killed all right, but my money's on Curly as the shooter.

1951: ROOTY TOOT TOOT, DIRECTED BY JOHN HEBLEY (UPA)

This stylish seven-minute cartoon offers its own unique and witty take on the story. You should really watch it for yourself, but I will just say here that the court finds Frankie innocent of Johnny's killing, but sends her to jail for murder anyway.

It's title, of course, comes from the original ballad's description of the noise Frankie's gun made as she pulled the trigger: "Rooty-toot-toot, three times she shot / Right through that hardwood door".

Rooty Toot Toot was directed by John Hubley - best known as the creator of Mr Magoo - for UPA's Jolly Frolics series. Frankie's singing voice was provided by Annette Warren, who'd done the same job for Ava Gardner in Show Boat earlier that year. The cartoon was nominated for an Oscar as Best Animated Short Film in 1951, but lost out to Tom & Jerry's The Two Mousketeers.

[Thanks to Rebecca Goldman for drawing this cartoon to my attention.]

1966: FRANKIE & JOHNNY, STARRING ELVIS PRESLEY (MGM)

Frankie & Johnny here are singers working on a Mississippi riverboat. Johnny's also an unlucky gambler, who regularly loses his money at the boat's roulette table, and Frankie despairs that he'll ever settle down and marry her. "You know what I'd do if he ever done me wrong?" she asks, miming a pistol with her right hand. "Bang! Bang! Bang!"

Johnny consults a gypsy fortune teller, who tells him he needs a lucky redhead to restore his fortunes. Frankie, unfortunately, is a blonde. Meanwhile, the flame-haired Nellie Bly arrives on the boat to resume her romance with Clint Braden, its owner.

Seeing all this, Johnny's pal Cully writes a song about the three of them, which turns out to be the ballad we all know. Frankie, Johnny and Nellie stage this number at the show that night in a casino scene which culminates with Frankie shooting Johnny. There's a lot of nonsense involving identical Mardi Gras costumes and identity mix-ups as Frankie and Nellie try to make their respective men jealous. Johnny kisses Nellie (thinking she's Frankie), and wins a lot of money. Braden starts to worry that Johnny might steal Nellie from him.

At the show that night, Braden's comic stooge replaces the blanks in Frankie's stage gun with real bullets, thinking he's doing his boss a favour. What he doesn't know is that Braden's just asked Nellie to marry him and she's accepted. Frankie fires the gun and Johnny collapses, but luckily the bullet hits the charm medallion which Frankie gave him earlier. Everyone laughs off the stooge's attempt at murdering an innocent man and the credits roll. Even Nellie turns out to be quite nice in the end.

1991: FRANKIE & JOHNNY, STARRING AL PACINO AND MICHELLE PFEIFFER (PARAMOUNT)

We know the Frankie & Johnny in this modern-day New York love story have both heard the ballad, because they tell one another so, but that's as far as the link goes. Far from doing Frankie wrong, this Johnny pursues her relentlessly throughout the entire movie and finally persuades her to accept his love.

The song's acknowledged a few times in the dialogue ("Didn't they kill each other?"), we get a verse of James Intveld's version on the soundtrack, and that's your lot. London's Sound Theatre quoted the ballad's lyrics on their posters when they staged Terrence McNally's source play in 2005, but his plot's got nothing to do with the originals either.

Sources and Footnotes

1) Frankie & Johnny, by John Huston (Benjamin Blom, 1968)

2) The Real Story of Frankie & Johnny, by Dudley L. McClure (published in Daring Detective Tabloid, June 1935)

3) We Did Them Wrong: The Ballad of Frankie & Albert, by Cecil Brown (published in The Rose & The Briar, ed. Sean Wilentz & Greil Marcus, WW Norton & Co, 2005).

4) The name Nelly Bly first appeared as the title of an 1850 minstrel song, composed by Stephen Foster. It was then adopted as a pen name (spelt "Nellie Bly") by the journalist Elizabeth Cochrane, who became famous in 1889 when she recreated Phineas Fogg's trip from Around The World in Eighty Days. The name would still have been familiar to Americans as Frankie's song became popular, but perhaps staring to drift free of its context. Neither Foster's character nor Cochrane's alter-ego had any connection with Frankie's story, but the sound of the name echoed Alice Pryar's quite closely, and this substitution gave singers a less awkward line to negotiate. It's my guess that Nellie replaced Alice in the cast for that reason alone.

5) Immortalia, by A Gentleman About Town ( Parthena Press, 1969). Dan Clowes adapted this version into a three-page comic strip, which appears in his 2002 Fantagraphics collection Twentieth Century Eightball.

6) St Louis Post-Dispatch, February 13, 1942.

7) Frankie, by Mississippi John Hurt (Okeh, 1928).