For bereaved Londoners in 1850, finding a cemetery where their loved ones could be left to rest in peace was no easy matter.

For bereaved Londoners in 1850, finding a cemetery where their loved ones could be left to rest in peace was no easy matter.

The capital's population had more than doubled in the first half of the 19th Century, and the number of London corpses requiring disposal was growing almost as fast. But cemetery space in the city had spectacularly failed to keep pace. This led to graves being desecrated and re-used with alarming regularity, disinterred bones left scattered across the churchyard grass and a greatly-increased risk of disease as material from decomposing bodies leaked into nearby drinking wells and springs. Matters finally came to a head with the cholera outbreak of 1848-49, which killed nearly 15,000 Londoners and made it clear that drastic action was needed.

The man who came up with the answer was Sir Richard Broun. In 1849, he proposed buying a huge tract of land at what is now the Surrey village of Brookwood to build a vast new cemetery for London's dead. The 2,000-acre plot he had in mind - soon dubbed “London's Necropolis” - was about 25 miles from the city, which meant it was far enough away to present no health hazard and cheap enough to allow for affordable burials there. The railway line from Waterloo to Southampton, Broun realised, could offer a practical way to transport coffins and mourners alike between London and the new cemetery.

The idea of using the railways to link London to the new rural cemeteries it so obviously needed had been in the air for some years when Broun presented his plan, but not everyone was convinced. Many thought the clamour and bustle they associated with train travel would not suit the dignity demanded of a Christian funeral.

There were other fears too. In 1842, questioned by a House of Commons Select Committee, Bishop of London Charles Blomfield said he thought respectable mourners would find it offensive to see their loved one's coffins sharing a railway carriage with those of their moral inferiors. “It may sometimes happen that persons of opposite characters might be carried in the same conveyance,” he warned. “For instance, the body of some profligate spendthrift might be placed in a conveyance with the body of some respectable member of the church, which would shock the feelings of his friends.”

Such objections sound foolish to modern ears. But it is worth remembering that, in 1842, train travel itself was still a novelty. George Stephenson had introduced the first regular passenger service as recently as 1830, and it was probably inevitable that extending this noisy innovation to funeral traffic would prove controversial. John Clarke, author of The Brookwood Necropolis Railway, says: “Train travel was still seen as revolutionary. The first through train from Waterloo to Southampton ran in 1838, which is the date of that route being fully opened. Waterloo itself was only completed in 1848, and the first Necropolis Station came along just six years after that. Arguably, at that time, it was a major addition to the service.”

Andrew Martin, who researched the funeral trains while preparing to write his thriller The Necropolis Railway, adds: “When trains first came along, people had a very different attitude. Trains were regarded like cars are now, really. People were scared of them, they were thought of as dirty, noisy things. That was a very mid-Victorian attitude. Dickens hated trains.”

Despite this suspicion of rail travel, MPs took Broun's idea seriously and, in June 1852, they passed an Act of Parliament creating The London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company, a name which was later shortened to The London Necropolis Company. London & South Western Railway became LNC's partners in the scheme, and looked forward to making an estimated £40,000 a year from the extra fares they believed the service would produce. LNC bought two thousand acres of Woking Common land from Lord Onslow, and set aside 500 acres of that for the cemetery's initial stage.

Even with all this in place, however, several delicate problems remained to be solved. L&SWR's shareholders had already decided that they did not want the passenger stock they were lending to LNC mixed up with the carriages used on their mainstream passenger services. If L&SWR's existing customers suspected they were being asked to travel in carriages which had earlier been hooked to a funeral train, the directors feared, they would stay away in droves. It was decided, therefore, that the Necropolis trains would have to be run as an entirely separate service, with its own dedicated rolling stock and timetable.

The Bishop of London's objections were addressed by ensuring that every Necropolis train would offer six distinct categories of accommodation, and that dead passengers would be given just as wide a choice as their live companions.

The first distinction was between conformist funeral parties and non-conformist ones. In a train carrying two hearse cars, for example, one would be reserved for the Church of England's dead, and the rest for everyone else. The passenger carriages would be allocated on the same principle, and each hearse car yoked to the appropriate passenger section. Following this idea through, LNC took care to plan for two stations at Brookwood. One would serve the conformist area on the sunny south side of the cemetery, the other the chilly non-conformist graves on its north side.

The second distinction depended not on what religion you were, but on whether you bought a first-class, second-class or third-class ticket. As with train travel today, each class offered a few more home comforts than the one below it, and each cost a great deal more than the last. Coffin accommodation was divided into three classes too, with each hearse car split into three sections of four coffin cells each. LNC justified the higher fares it charged for first-class coffin accommodation by pointing to the higher degree of decoration provided on its first-class coffin cell doors and the greater degree of care which first-class coffins were given at both ends of the journey.

Throughout 1854, work to prepare the new service proceeded at a frantic pace. Work on designing and building a London terminus just outside Waterloo for the service started in March of that year. By July, the two cemetery stations were complete. The first sections of branch line track to take trains off the main line and through Brookwood's grounds were laid in September. In October, the London terminus was completed and the first two custom-built hearse cars ordered. Timetables were drawn up allowing for a daily service between London and Brookwood (Sundays included) and detailed rules devised for passengers and corpses of every class. On November 7, 1854, Brookwood's grounds were consecrated and, finally, nothing remained to be done. Six days later, the world's first funeral train was ready to roll.

Throughout 1854, work to prepare the new service proceeded at a frantic pace. Work on designing and building a London terminus just outside Waterloo for the service started in March of that year. By July, the two cemetery stations were complete. The first sections of branch line track to take trains off the main line and through Brookwood's grounds were laid in September. In October, the London terminus was completed and the first two custom-built hearse cars ordered. Timetables were drawn up allowing for a daily service between London and Brookwood (Sundays included) and detailed rules devised for passengers and corpses of every class. On November 7, 1854, Brookwood's grounds were consecrated and, finally, nothing remained to be done. Six days later, the world's first funeral train was ready to roll.

When LNC drew up its original plans for Brookwood, it hoped to create a cemetery big enough to take all of London's dead for centuries to come. “The idea was that it would take everyone who died in London,” says Martin. “It would simply be an alternative London - for the dead.”

LNC never got remotely close to fulfilling that ambition but, working together with L&SWR, it did expand the Necropolis service pretty relentlessly throughout its first 50 years. In 1855, cellars were added to the two cemetery stations, allowing their existing coffin reception areas to be turned into third-class waiting rooms. In 1864, a brand-new mainline station called Brookwood was opened, which stood directly opposite the cemetery's entrance and allowed normal passenger trains to stop there. In 1899, two larger coffin vans were built for the service, each capable of carrying 24 coffins instead of the original vans' 12.

This last development raises the question of how many corpses the Necropolis train might have carried when fully-loaded. First, let's consider the original hearse cars, each of which had a capacity of 12 coffin cells. Clarke says: “There could have been anywhere between four and eight 12-coffin hearse carriages provided at various dates after 1854, and it's quite conceivable that all of those would have been used on a single train. So far, the highest number of funerals we've discovered for a particular date is over 60.”

When it comes to the 24-coffin cars, the picture is slightly clearer. We know that no more than two hearse vans were used on any Necropolis service after 1899, which suggests a maximum load from that date onwards of 48 coffins per train.

As people got used to the trains, they gradually came to accept them, even bestowing affectionately tasteless nicknames such as “the dead meat train” or “the stiffs' express”. For those working at Brookwood, the Necropolis trains were simply part of their normal working day. Clarke says: “One of my earliest contacts at Brookwood was one of the old masons who used to work there. He made the point that, when he worked in the masons' yard and the train was running, it wasn't anything special. It was just a way of life. It's extraordinary to us now, but it was very ordinary to him.”

Even Clarke's mason might have been impressed by one particularly spectacular Brookwood funeral in 1891. Charles Bradlaugh, who died on January 30 that year, was a well-known freethinker and founder of the National Secular Society. Throughout his life, he championed then-unfashionable causes such as birth control, republicanism, atheism and anti-imperialism. He wrote for The National Reformer under the pen name Iconoclast, went on to edit the paper, and later published a controversial pamphlet favouring birth control which led to his arrest. He was sentenced to six months' imprisonment, but successfully appealed and had his conviction overturned on a legal technicality.

In 1880, Bradlaugh was elected as Liberal MP for Northampton, but prevented from taking his seat in the Commons when other MPs claimed that his atheistic beliefs prevented him from properly taking the oath. Nothing daunted, Bradlaugh stood in three successive by-elections at Northampton, won every one, and was eventually allowed to take his seat in 1886. Two years later, he succeeded in passing new legislation allowing atheists to affirm an oath in Parliament or the courts, rather than swearing by a god they did not believe in. He was still MP for Northampton when he died, by which time his strong support for Indian self-rule had won him the nickname “the Member for India”.

Bradlaugh died on January 30, 1891, and his funeral was arranged for February 3. The day before the funeral, his body was taken to LNC's York Street station, where it lay in a private mortuary overnight. Next morning, it was taken down to Brookwood by the normal Necropolis train. That morning, the streets around Waterloo were jammed with thousands of mourners hoping to attend Bradlaugh's funeral, and LNC was forced to lay on three special afternoon trains to accommodate them.

Bradlaugh was buried in a family plot on the non-conformist north side of the cemetery. Many of London's resident Indian population were at the graveside to pay their respects, including Mohandas Gandhi - later the Mahatma - then just 21 years old and studying law at University College, London. Gandhi later reported overhearing a noisy row while waiting for his return train at North Station, where he found an atheist and a clergyman deep in furious debate.

A bronze bust of Bradlaugh was bought by public subscription and placed on his grave. In a bizarre postscript, however, this bust was stolen on September 12, 1938, the night before a group from the World Union of Freethinkers was due to visit Bradlaugh's grave. It's never been replaced.

The next big change in the service came when L&SWR realised that the LNC's York Street terminus was severely restricting its passenger services' access to Waterloo by creating a bottleneck there. If the growing rail company was going to build the extra passenger lines it needed at Waterloo, it would have to demolish York Street terminus first. But the LNC had a 999-year lease on the property, and that gave it the whip hand in all the negotiations that followed.

The next big change in the service came when L&SWR realised that the LNC's York Street terminus was severely restricting its passenger services' access to Waterloo by creating a bottleneck there. If the growing rail company was going to build the extra passenger lines it needed at Waterloo, it would have to demolish York Street terminus first. But the LNC had a 999-year lease on the property, and that gave it the whip hand in all the negotiations that followed.

L&SWR did eventually persuade LNC to give up York Street, but only after agreeing to build a replacement station for the company, give it a new 999-year lease at a peppercorn rent, pay £12,000 in compensation for LNC's inconvenience, supply a new train for the Necropolis line and agree to accept LNC tickets for travel back to London on L&SWR's other, more expensive, services.

The discrepancy in ticket prices had arisen because LNC's fares were fixed by the 1854 Act which created the company, and not increased again until 1939. By 1902 - the year in which LNC's replacement terminus opened - this had produced a situation where a first-class return ticket from Waterloo to Brookwood cost eight shillings on L&SWR's normal service, but only six shillings on the Necropolis trains. Golfers travelling from London to West Hill Golf Club, which stood right next to Brookwood's grounds, sometimes took advantage of this, dressing up as mourners to ride the Necropolis train down, and so pay a lower fare. The remains of a rough footpath from Brookwood Station to West Hill's clubhouse can still be seen at the cemetery, and Clarke believes it was cheapskate golfers who originally tramped it down.

The site selected for LNC's new London terminus was just behind Waterloo Station at 121 Westminster Bridge Road. Like York Street, the building was equipped with two mortuaries, caretaker's accommodation, waiting rooms of various classes, workshops and all the usual station facilities. In the case of Westminster Bridge Road, however, L&SWR's enforced largess also made it possible to also give the station its own mortuary chapel, where bodies could be laid in state for a while or funeral services arranged for mourners unable to make the trip to Brookwood. The new station opened for business in February 1902.

As the Twentieth Century began, then, the Necropolis Railway looked like it was in pretty good shape. But, even in the first 20 years of its operation, the number of people using Brookwood never came close to the hordes LNC had envisaged. Between 1854 and 1874, the cemetery averaged only 3,200 burials a year, accounting for less than 6.5% of London's deaths at the time. Many of the “missing” bodies would have gone instead to one of the 32 new London cemeteries opened during the same 20-year period.

The first sign of the disappointing demand for graves at Brookwood came in October 1900, when the Necropolis Railway dropped Sunday services from its timetable. The frequency of the service declined steadily from that point onwards until, by the 1930s, it was running only once or twice a week. The London authorities which provided all those new cemeteries must take part of the blame. The introduction of the motor hearse, which made its English debut in 1909, did not help either. When the Necropolis Railway's final death blow came, however, it was neither of these factors that delivered it. That task fell to the German Luftwaffe.

April 16, 1941, was one of the worse nights of the London Blitz. Thousands of high explosive and incendiary bombs rained down on the city that night, starting over 2,000 fires and costing more than 1,000 Londoners their lives. Westminster Bridge Road, where the Necropolis train was berthed in its siding overnight, did not escape. By next morning, all that remained of the terminus was its platforms, first class waiting rooms and office accommodation. The mortuary chapel, the workshops, the caretaker's flat and the station's entrance driveway were all destroyed. Reports written the day after the air raid describe the Necropolis train itself as being “wrecked” or “burnt out”. LNC closed the station down, stopped running the Necropolis trains and waited for the end of the war to decide whether it should rebuild.

LNC looked at the service again in 1945, but soon concluded that it was no longer a commercial proposition. Even with compensation from the War Damage Commission, rebuilding the Westminster Bridge Road Station would have been expensive. Replacing the rolling stock destroyed or damaged in the raid would have cost money too, as would getting the cemetery's now-neglected line back up to scratch. Demand for the trains had all but disappeared even before the air raid, and it was clear this amount of investment could not be justified. The Necropolis Railway had breathed its last.

Although the Necropolis trains themselves ended in 1941, there is some evidence that single coffins continued to be conveyed to Brookwood by rail well into the 1950s. The most likely procedure seems to be that the coffin would be loaded into the luggage space of a passenger service's brake car, the mourners would travel down in reserved compartments on the same train and everyone would transfer to waiting cars at Brookwood for the remainder of the ceremony.

Transporting the dead in this way was much more common than we now imagine, and many passenger rail services around the country sometimes carried coffins in their brake vans. This led to a particularly grisly spectacle on June 21, 1912, when a passenger train travelling from Manchester to Leeds was derailed near Hebden Bridge. A coffin containing the remains of Charles Horsfield was ejected from the brake van and its contents spilt on to the track. The next day's Halifax Courier reported: “The coffin was found all splintered and the corpse, though unmarked, was pinned under the debris and partly exposed”. A rumour at the time - apparently untrue - insisted that Horsfield's body was one of those recovered after the sinking of The Titanic just ten weeks earlier.

It was not until 1988 that British Rail announced it would no longer carry coffins. “There's been a sea-change in how funerals operate,” says Clarke. “The railways were used for carriage of coffins until relatively recently. Now, I think it's virtually impossible to transport a coffin by rail.”

In the sixty years since 1941, almost all physical evidence of the Necropolis line has disappeared. The frontage of the Westminster Bridge Road station is still there, although the words “London Necropolis” which once appeared over its main entrance have gone. There's still a train service from Waterloo to Brookwood, but all the rail lines inside the cemetery were removed in about 1947.

In the sixty years since 1941, almost all physical evidence of the Necropolis line has disappeared. The frontage of the Westminster Bridge Road station is still there, although the words “London Necropolis” which once appeared over its main entrance have gone. There's still a train service from Waterloo to Brookwood, but all the rail lines inside the cemetery were removed in about 1947.

The two cemetery stations survived for a while as refreshment bars, but both have now been demolished. North Station (by then North Bar) was closed around 1956 and demolished in the early 1960s because of dry rot. South Station (South Bar) was closed in about 1967 and used as a mortuary and storage building for the next five years. In September 1972, it was badly damaged in a fire thought to have been set by vandals, and bulldozed soon after. All that remains of the two cemetery stations now is their platforms, complete with the characteristic dip in their trackside edges to help LNC staff unload coffins from the hearse vans' bottom shelves.

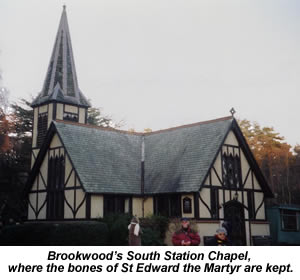

The two stations' chapels have also survived. South Station Chapel has been carefully restored by the St Edward Brotherhood, an orthodox order of monks who worship at the chapel and maintain a shrine there containing the bones of St Edward the Martyr. The Brookwood Cemetery Society conducts regular walking tours of the cemetery, following the route of its old railway line and pointing out the odd bit of track hardware which remains.

Despite losing so many of its relics, the Necropolis Railway continues to exert a strong hold on writers' imagination. The first book to tackle the subject in recent years was Basil Copper's Necropolis, a 1980 crime novel which uses the funeral trains as its setting. The first edition of John Clarke's history of the service followed in 1983 and Andrew Martin's murder mystery in 2002.

Clarke first became fascinated by the trains in the mid-seventies, when his interest in the First World War led him to visit Brookwood's Commonwealth War Graves section. Strolling round the cemetery at random, he chanced on the remains of North Station, and wondered what a railway platform was doing in the middle of a cemetery. From that moment onwards, he was hooked. “It was the unusual nature of the railway that drew me in,” he says. “It was the first railway funeral service in the world and, as far as I'm aware, it was the one that lasted the longest.”

Martin's interest was sparked when researching Waterloo Station for his Tube Talk column in London's Evening Standard. “I bought a copy of the Oxford Companion to British Railway History, and I came across in there,” he recalls. “All the time I was writing Tube Talk, I kept on coming back to it. It was so moody and so atmospheric. The whole thing seemed to have been invented exactly so that someone could write a novel about it.

“But, of course, it was very logical. It remains logical. I think it would be rather nice to be carried to your last resting place on a train.”

This article first appeared in Fortean Times 179 (January 2004). The Brookwood Cemetery Society offers regular guided tours, including one which follows the route of the old rail line. For details, see www.tbcs.org.uk.

Adam Leat's short film about the Necropolis Railway, which he built round a PlanetSlade interview narrating the story, can now be viewed on-line here.

Episode 43 of Monocle Radio's The Urbanist opens with PlanetSlade discussing The Necropolis Railway. First broadcast August 11, 2012. Free audio here.

Appendix I: The benefits of first-class travel

For anyone who could afford it, first-class travel on the Necropolis trains conferred some very definite privileges. First-class passengers were relentlessly pampered at every stage of the journey, and constantly protected from having to mix with the lower orders.

The dead were no less segregated than the living, not only on the train but also at all the LNC's stations. “It is clear there were separate mortuaries for the better-off and the hoi poloi,” says Clarke. This situation reached absurd heights in 1918, when L&SWR abolished second class travel on all its services. It extended this change to the Necropolis trains' live passengers but forgot to include the dead ones. For the next 23 years, dead people on the service were offered three classes of accommodation to choose from, while live passengers had only two.

To illustrate the difference between the different classes of travel available, I've taken the example of a 1903 Necropolis run and assumed the funeral services involved would have taken place at Brookwood rather than in London. In cases like this, a horse-drawn hearse would usually collect the body from the deceased's family home and take it directly to LNC's London terminus as part of a funeral procession. LNC chaplains would travel down on the train and conduct whatever services were required at Brookwood.

1) At Westminster Bridge Road

i) First-class passengers

First class funeral parties were asked to arrive at the LNC's Westminster Bridge Road terminus at least ten minutes ahead of the train's scheduled 11:55am departure time. Mourners would be directed to one of the station's private waiting rooms, while the day's

first class coffins were hoisted one-by-one to platform level in the lift provided for that purpose.

When the coffin was ready for loading, the mourners were offered the option of

gathering on the first-class platform to watch it being slotted into a first-class compartment in the appropriate hearse carriage. A photograph from around this time shows a first-class coffin shouldered by four formally-dressed pall bearers as they prepare to load it onto the train.

When the coffin was safely on board, the funeral party accompanying it would be shown to their own private compartment on the train. The first-class fare in 1903 was six shillings for mourners (return) and £1 for coffins (single).

ii) Third-class passengers.

Third-class funeral parties would have to turn up at Westminster Bridge Road half an hour before departure time, where they would wait in a communal waiting room on the third-class platform. An opaque glass screen shielded this platform from the view of the toffs opposite.

Third-class mourners were not allowed to watch “their” coffin being loaded into its third-class compartment. The fare for third-class travel in 1903 was two shillings for mourners and two shillings and sixpence for coffins.

Third-class travel to Brookwood may have been basic, but at least it offered the poor an affordable way to promptly bury their dead. When only more expensive conventional funerals had been available, poor families would often keep the corpse at home for over a week while they scraped together the undertaker's fees required.

2) In transit

The Necropolis train left Westminster Bridge Road at 11:55am and was scheduled to arrive at Brookwood at 12:52pm. This produces a journey time of 57 minutes, one of the few features of the Necropolis train which was exactly the same for passengers of all classes.

3) At Brookwood

i) First-class passengers

The train would pull off the mainline at Necropolis Junction and run onto the single-track line taking it through the cemetery itself. Proceeding at a respectful walking pace, its first stop would be North Station.

First-class passengers with non-conformist bodies to bury would be taken to the chapel near North Station, while the appropriate coffin was loaded onto a hand bier for the same trip. A funeral service could then be held at the chapel before everyone moved on to committal at the graveside.

Meanwhile, the train would proceed to South Station, where Anglican funeral parties could go through exactly the same procedure.

ii) Third-class passengers

Non-conformist third class funeral parties would also be directed to the chapel, where a single service would be said over all the appropriate coffins from that particular train load.

However, it is worth pointing out that even a third-class (or “pauper class”) body got a plot to itself at Brookwood, as opposed to the communal pit which it would have been consigned to at many other cemeteries of the time.

3) The Return Journey

i) First-class passengers

After the committal service, mourners could either enjoy a pleasant walk through Brookwood's grounds, or return directly to their station, where they could wait in a private room for the train to take them back to London.

The train was scheduled to leave Brookwood at 2:35pm, allowing mourners time to enjoy lunch or a drink in the station's refreshment room. If all went according to plan, they would be back at Westminster Bridge Road at 3:26pm.

ii) Third-class passengers

Third-class passengers would also return to the station after their own committal services, but had to share a communal waiting room when they got there. It is not clear whether third-class passengers were allowed to use the stations' refreshment rooms.

Appendix II: Boozing at Brookwood

One controversial decision made by the London Necropolis Company was that the refreshment rooms at its cemetery stations should serve alcoholic drinks. It is said that each of these rooms had a sign above the bar reading: “Spirits served here”. If so, no doubt the concession was appreciated by Brookwood's permanent residents.

There are several tales of drunken behaviour on and around the Necropolis trains, although the station bars were not always to blame. On one occasion in the 1850s, two mourners turned up at LNC's York Street station in such a state that the caretaker refused to let them board the train. A ticket collector on another Necropolis train found one group of passengers so drunk that they were dancing round their carriage during the return journey to London.

Sometimes the staff got drunk too. On January 12, 1867, the Necropolis train's driver enjoyed a liquid lunch while waiting for the day's funerals to be completed. When he reported back for duty, he was clearly incapable of driving the train, so the fireman had to take over and pilot it back to Waterloo. The driver was sacked.

When the matter came to be investigated, L&SWR suggested that the driver must have gotten drunk at one of the cemetery stations. LNC denied this, saying he had not been served on their premises, but had retired to a nearby public house instead. It was eventually decided that LNC would supply all future train crews with a free ploughman's lunch and a single pint of beer so they wouldn't be tempted to go to the pub.

Sources

In writing this article, I have drawn heavily on the information in John M Clarke's The Brookwood Necropolis Railway (Oakwood Press, 1995). It's available here.

Other sources inlude:

* An Introduction to Brookwood Cemetery, by John M Clarke (The Brookwood Cemetery Society, 2002).

* Charles Bradlaugh: The Man of Action who Founded the National Secular Society, by David Tribe. National Secular Society website (www.secularism.org.uk).

* Guinness Book of Records, edited by Norris and Ross McWhirter (Guinness Superlatives Limited, 1970).

* The Times London History Atlas, edited by Hugh Clout (Times Books, 1997).

* The Charlestown Curve Derailment of June 1912, by Stuart Morris (Platform, Winter 2001).

* Express Wrecked Near Hebden Bridge, by “our own reporters” (The Halifax

Courier, June 22, 1912).

* Great Lives of the Century, edited by Arleen Keylin (New York Times Company / Arno Press, 1977).

* Necropolis, by Basil Copper (Sphere, 1981).

* The Necropolis Railway, by Andrew Martin (Faber & Faber, 2002).