It was a remarkable ceremony - and not just because the bride and groom were both eight feet tall.

It was a remarkable ceremony - and not just because the bride and groom were both eight feet tall.

Queen Victoria had personally wished the couple well and given them the jewellery they now wore. The bride made her way up the aisle following the world's most famous singing Siamese twins, who then took a place in the front pew. Crowds of gawping strangers filled the rear of the church, jostling with newspaper reporters and society columnists for a better view. A mob of even rowdier spectators packed the central London square outside, where the police struggled to keep control.

Still, at least the Daily Telegraph was sympathetic. "A man may get used to being eight feet high," it told readers. "But to be eight feet high and to be stared at by a devout congregation of idlers on the occasion of marrying a lady who is eight feet high also is a trying conjunction of matters. However, Captain Bates got through his difficulties tolerably well" (1).

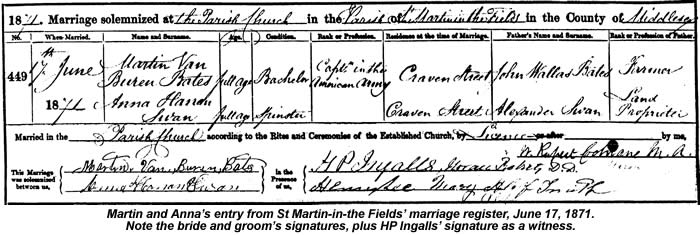

The scene of Captain Bates' ordeal was St Martin-in-the-Fields church in Trafalgar Square on June 17, 1871. Martin van Buren Bates and his bride-to-be Anna Swan had first met in New Jersey two years earlier, and been unexpectedly reunited in April 1871 while sailing from New York to Liverpool with HP Ingalls' small circus troupe. They were both famous attractions by that time, Anna having exhibited herself for nine years and Martin for about six. Ingalls' troupe was completed by Millie and Christine McKoy, a pair of harmonising Siamese twins who billed themselves as "Millie-Christine, the two-headed nightingale".

Martin and Anna, who barely knew each other before the ten-day voyage, were surprised to meet again on-board, as neither had known who else would be in the party when they joined. They began to spend a lot of time together, however, and by the time the ship docked at Liverpool on May 2, they were ready to announce their engagement. They'd each had several marriage proposals before, but always turned them down for fear that the suitors involved were really after the money and fame they'd earned in their sideshow careers. This time, it was different.

The troupe's three-year stay in Europe began with a week in Liverpool, where Martin and Anna stayed at the city's Washington Hotel. Anna's career had brought her to Liverpool before but it was Martin's first visit. His commission in the Confederate Army had given him an undeniable military bearing, and this fact did not escape the Liverpool Daily Courier. "He is probably the finest specimen of a giant that our degenerate modern days have witnessed," it said. "He is a handsome, well-proportioned young fellow, neither weak-kneed nor round-shouldered, as well set-up as any of Her Majesty's Foot Guards" (2). The Daily Post added that Martin's conversation was "that of a self-possessed and highly intelligent London gentlemen" (3).

The couple spent their first day in Liverpool riding round the city in a carriage to publicise the coming shows. Crowds gathered wherever they passed, and rumours began that they planned to marry. Everyone was delighted when they confirmed these plans two weeks later at a fashionable London reception, and Martin rented a London house for them at 45 Craven Street, next to the busy Charing Cross railway station.

At the end of May, Martin and Anna - by then billing themselves as "The Tallest Couple Alive" - gave their first public performance together at an unidentified London venue. This would have been far more refined than the vulgar carnival affair we might imagine today. Martin would read some poetry, Anna would play the piano, and then the couple might mingle with their paying guests, chatting politely and sipping tea. Sometimes, they would perform in short playlets written around their size. Evenings like this became a great success in London society, and it wasn't long before Buckingham Palace summoned Martin and Anna to appear before Queen Victoria herself.

Victoria - then nearing a decade of mourning for her beloved Albert - was captivated by the giant sweethearts' charm, and presented them each with a huge gold watch. These were about the size of a saucer, studded with diamonds, and said to be worth $1,000 apiece. She also gave Anna a diamond cluster ring and a wedding gown as gifts for the coming nuptials (4). Some accounts claim she used her Royal clout to ensure that St Martin's, the monarch's parish church, was made available on Martin and Anna's chosen date.

Booking a central London church for a Saturday wedding in June at less than six weeks' notice can't have been a simple matter, even in 1871, so perhaps this suggestion is less fanciful than it seems. All that would have been needed was for Victoria's staff to discretely make the Queen's wishes known.

The weather on the big day was dry, but with murky and overcast skies. Sunshine, the Telegraph reported, was "transitory and fitful". Martin arrived at the church around 10:45am, and found a large crowd already gathered there hoping to catch a glimpse of him or Anna as they arrived. He took his place at the altar, and Anna arrived a few minutes later. She was preceded up the aisle by Millie-Christine.

Ingalls gave Anna away at the altar, and the ceremony was conducted by Rev. Rupert Cochrane, a 6' 3" friend of Anna's Nova Scotia family, who happened to be preaching in London at the time. Martin wore Victoria's gold watch and Anna the diamond cluster ring. I assume the lace gown Anna wore must have been the one Victoria gave her too - surely the offer would have been impossible to refuse? - but I've yet to see any confirmation of that.

The rear pews of the church were full of curious spectators, creating what Harper's Bazaar sarcastically called "a reverential scene of whispering, giggling and climbing over pews" (5). The Telegraph was less sniffy, saying that "any disturbance was certainly not provoked by the group near the communion rails". Millie-Christine's arrival inevitably caused a bit of a fuss - Harper's mentions "a buzz of comment and much hilarity" - but the Telegraph's man noted that she, like everyone else in the wedding party, did her utmost to ensure the day did not turn into a circus.

"The bride's dress became her well," the Telegraph continued. "And there was something of stateliness and dignity in the skill with which she managed a most imposing train. [...] Captain Bates, the bridegroom, may be pardoned for having looked rather less at ease in a blue coat, white waistcoat and grey or light-tinted trousers." Harper's was unable to resist another snide comment at this point, remarking on the need to excuse Martin's "exceedingly blue tie".

"The bride's dress became her well," the Telegraph continued. "And there was something of stateliness and dignity in the skill with which she managed a most imposing train. [...] Captain Bates, the bridegroom, may be pardoned for having looked rather less at ease in a blue coat, white waistcoat and grey or light-tinted trousers." Harper's was unable to resist another snide comment at this point, remarking on the need to excuse Martin's "exceedingly blue tie".

After signing the register, the newlyweds struggled through the crowds outside, making for their carriage and the Craven Street wedding breakfast that awaited them. If the mob blocking their path had known a little more about Martin's bloodthirsty progress through the American Civil War, they might not have been quite so quick to get in his way.

Martin van Buren Bates was born on November 9, 1837, although he seems to have finessed this date a little in later life to extend his career (6). He was the 11th and youngest child of Kentucky farmers John and Sarah Bates.

The rest of the family were all normal size, and there seemed nothing exceptional about Martin until he turned seven. Then he began growing so fast - first fat, then tall - that his parents began fearing for his health and spared him from working on the farm. Instead, Martin concentrated on his education, learning to recite historical dates and events from memory by the time he was eight. Friends who knew the adult Martin credited him with what they called "almost a photographic memory", and this trait seems to have developed early.

We don't have a record of Martin's height at this point, but we do know that he weighed 170lbs (just over 12 stone) at age 11 and 300lbs at 13. He was, as one astonished uncle remarked, "a mighty big boy, by heck".

In his early twenties, Martin travelled to the nearby town of Whitesburg, passed the exams needed for his teaching certificate, and began working in a small log schoolhouse near the Bates' farm. "That 'Big Boy Bates' was a fellow none of us boys ever sassed," a former pupil recalled. "We didn't dare. Why, he was so big, his voice just sort of rumbled like a bull bellowing" (7).

The US Civil War started in 1861, and Martin joined up that September, fighting on the Confederate side as a private with the Fifth Kentucky Infantry. His courage quickly won him a string of battlefield promotions culminating - for the moment - in the rank of First Lieutenant. He fought in battles all over the state, including those at Middle Creek and Cumberland Gap, and did so with such ferocity that Unionist troops soon started singling him out. To them, he was "that Confederate giant who's a as big as five men and fights like 50".

Martin was seven feet tall by this time, and must have made a truly terrifying sight on the battlefield. His great great nephew Bruce Bates describes it like this: "He used two colossal 71-calibre horse pistols that had been made specially for him at the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond. He wore them strapped across his chest in black leather holsters. He had a sabre that was 18 inches longer than the standard weapon. He rode a huge Percheron horse that he took from a German farmer in Pennsylvania" (8).

God knows how they did it, but somehow Unionist troops managed to capture Martin in Pike County, Kentucky, early in 1863. His first taste of life in showbiz came while imprisoned at Camp Chase in Ohio, where Union soldiers nick-named him "The Kentucky Giant" and came to gawp at him in his cell. He was later moved to another Union camp at Point Lookout, Maryland where, depending on whose account you believe, he either escaped or was freed in that May's exchange of prisoners (9).

When the Kentucky Infantry was disbanded in November 1863, Martin joined the Virginia Infantry, only to find his unit there merged with the Seventh Confederate Cavalry, where his brother Robert was already serving. It was during his cavalry service that Martin made captain, a rank he continued to use for the rest of his life.

One of his duties in the Seventh was to help suppress the anarchic guerrilla bands who robbed and murdered Kentucky and Virginia families throughout the Civil War. These men were neither Confederate nor Unionist, but simply out for themselves. When one gang in Crane's Nest, Virginia, became particularly troublesome, Martin took a group of men out there and found the gang's hideout at dead of night.

Burdine Webb takes up the story in her 1941 essay The Giant of Letcher County: "A fire was hurriedly built. The flames spread upward, lighting a considerable distance and the soldiers put themselves in readiness. The guerrillas swept down to see about the conflagration, when hundreds of shots ran out. Twelve of the band fell, rolling down the mountainside. Twelve or 15 more were captured. The ruse worked well" (10).

Martin's most memorable Civil War adventure was yet to come, however. Returning on leave to the family farm near Whitesburg, he found local Unionist sympathisers had kidnapped one of his brothers and tortured him to death with their bayonets. Martin was enraged by this, gathered his men together, and set off to find the killers. One by one, they rounded them up, dragging some from their beds and winkling others out from the hilltop caverns where they'd chosen to hide.

The eight captured men and their families were route-marched to a spot called Big Hollow and held there overnight. Wives, parents, grandparents and children of the condemned were all dragged along. Some of the women were pregnant, and some of the children so young that they had to be carried.

Martin's men found two slim oaks growing about 12 feet apart and lashed a horizontal pole between them, about ten feet above the ground. Then they stripped a long beech log of its branches, laid that on the ground beneath, and strung eight nooses from the pole. At dawn, they awoke their prisoners.

Here's how Bruce Bates describes what followed: “At the sight of the dangling ropes, the women began to wail. The giant appeared on his giant horse, his giant sword and pistols gleaming, his black eyes shining with contempt and hatred. His men appeared out of the gloomy mists herding the prisoners before them, each man's hands bound behind his back.

Here's how Bruce Bates describes what followed: “At the sight of the dangling ropes, the women began to wail. The giant appeared on his giant horse, his giant sword and pistols gleaming, his black eyes shining with contempt and hatred. His men appeared out of the gloomy mists herding the prisoners before them, each man's hands bound behind his back.

“The prisoners were placed on the log, and a noose was dropped around each shrinking neck, the men pleading for their lives. [...] Then the giant raised his hand in a signal. Two men gave the log a shove and it rolled down the hill. The eight bound figures dropped a few inches and choked slowly to death. With swords and cocked pistols the women and children were kept at bay. None could render aid” (8).

But Martin had left the best till last. “The giant told the people not to touch the dead or take them down from the gallows,” Bruce says. “They were to hang there and rot by the road, their corruption warning all passers-by of the consequence of killing a Bates. If anyone violated his order, they would die in the same way. Absolutely no mercy would be shown. In addition, his family would be destroyed, his house burned, his stock killed. 'Take warning,' the giant said. 'Because no other warning will be given!' Then he and his men rode away, leaving the dead to twist in the wind and their kin to mourn them.”

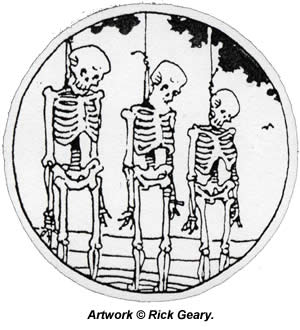

It was only when Martin returned briefly to Whitesburg at war's end in 1865 and gave his express permission for the bodies to removed that anyone dared touch them. “The bodies turned to skeletons before the giant came back,” Bruce tells us. “Only rattling bones were left for burial.”

Martin refused to stay in Kentucky after the war, saying he wanted no part of the local feuds that continued there as old Civil War resentments played themselves out. He may also have feared that the families of the men he'd lynched would one day come in large enough numbers to extract a revenge of their own. “I've seen enough bloodshed,” he told his nephew John Wright. “I don't want any more.”

Instead, Martin and John travelled to Cincinnati together, where they began working in Robinson's Circus. John performed as a trick rider and a sharpshooter there, while Martin exhibited himself and read poetry to show off his education. It was around this time that he reached his peak height of 7' 11½” and his settled weight of 525lbs. He was about 28 years old.

Four years later, Martin met Anna for the first time, while visiting the New Jersey home of General Winfield Scott for what seems to have been a social occasion. Anna, who was touring the US with PT Barnum's Circus, had been brought to the great impresario by HP Ingalls, who clearly never forgot her. In 1871, he signed Martin, Anna and Millie-Christine to individual contracts for the Barnum show he planned to take to Europe. Martin and Anna boarded the City of Brussels in New York Harbour for the trip to Liverpool on April 22, 1871. Less than two months later, they'd be married.

Martin and Anna's neighbours made them welcome in Craven Street, but the couple had little chance to settle there for the next six months. First came their honeymoon in Richmond, Surrey, where they stayed at an inn called the Star & Garter. Martin was so amazed at the exorbitant bill presented to them when they left - £17 - that he took it home with him and framed it.

They had a few weeks in London before embarking on their first UK tour, and used this time to squeeze in three more Royal Command appearances. First, they met the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) at the Masonic Hall, where Grand Duke Vladimir from Russia and Prince John of Luxembourg also attended. Then came another performance for Victoria, and finally an encore for the Prince of Wales at Marlborough House. Less elevated Londoners got a chance to see them too, thanks to appearances at both St James's Hall and the Crystal Palace.

The UK tour billed Martin and Anna as “The Largest Married Couple in the World” and took them as far north as Edinburgh. It was nearly Christmas when the couple returned to Craven Street. In April 1872, they took part in a gala benefit show at Astley's Amphitheatre in London, where they shared a bill with Millie-Christine, Tom Thumb and Blondin, the famous tightrope walker. The show was arranged to raise funds for a popular English showman, whose sudden death had left his widow and children facing destitution.

Anna must have been heavily pregnant during the Astley's show, because she gave birth just a month later. On May 19, 1872, she produced an 18lb baby girl, who died at birth and was never named. Her gravestone identifies her only as “Sister”.

Martin describes the birth in his autobiography The Kentucky River Giant. “Doctors Cross and Buckland were the physicians in charge,” he writes. “It was a girl weighing 18lbs and being 27” tall. This loss affected us both and by the advice of the doctors I took my wife upon the continent. There, we travelled for pleasure, only giving receptions when requested to do so by Royal Command” (11).

It's thought that Martin allowed Sister's body to go to the London Hospital, where it could be studied for research into the causes of gigantism. The London Hospital Museum exhibited a giant baby's remains a few years later, but we don't know whether these were Sister's or not.

After their trip to Europe, Martin and Anna briefly visited Ireland, and then returned to London. But Sister's death had left Craven Street full of unhappy memories, and neither of them had much stomach for remaining in the city. By June 1874, they were making plans to return to America.

Anna Swan was born in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia on August 6, 1846, weighing in at over 18lbs. All the rest of the family were normal size. Her father Alexander had emigrated from Dumfries in Scotland and married Ann, a Nova Scotia girl with ancestors in the Orkneys. Anna was the third of their 13 children and worked, like everyone else, on the family farm.

Anna Swan was born in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia on August 6, 1846, weighing in at over 18lbs. All the rest of the family were normal size. Her father Alexander had emigrated from Dumfries in Scotland and married Ann, a Nova Scotia girl with ancestors in the Orkneys. Anna was the third of their 13 children and worked, like everyone else, on the family farm.

When she was just four years old, Anna was already tall and strong enough to carry two full buckets of water up the steep hill to their log farmhouse. Alexander launched her showbiz career early, exhibiting Anna at Halifax as “The Infant Giantess”. One newspaperman seeing her there wrote: “This healthy child, 4 years 7 months, was as rosy as a milkmaid, weighed over 94lbs and already had arms and wrists as large as a full-grown man” (12).

Six months later, Anna was 4' 8” tall and weighed over 100lbs. By the time she turned six, her father had become accustomed to the regular task of demolishing and rebuilding her bed to keep up with her growth. At eight, she was routinely wearing her mother's dresses when she played outside, prompting one passer-by to stop and watch what he assumed was a retarded adult behaving like a child.

Anna's teachers made her as comfortable as they could at school by building up a table on planks to serve as her desk and allowing her to sit on a high stool there. She began to excel in music and literature, read all the classics and was considered an intelligent young lady. At home, she would sit on the floor, propping her back against the wall in order to eat at the family's standard-size dinner table. Her only escape from this infuriatingly Lilliputian world was to spend as much time as she could outside, where she took long, solitary walks in the countryside or read beneath a tree.

In 1860, a Quaker who'd seen Anna in New Annan told PT Barnum about her. Impressed by her measurements - the teenage Anna was then 7' 11” tall and weighed over 400lbs - he sent his scout, HP Ingalls, to find the giant girl and bring her to New York. Anna refused the offer, saying she had no interest in exhibiting herself and that her parents were against her moving to New York.

Instead, she spent that summer living with her aunt in the Nova Scotia town of Truro, and began attending school there. But her aunt's house lacked the modifications Dad had made at home, which left Anna feeling uncomfortable there. Finding the people of Truro followed her around staring wherever she went, she quickly tired of the experience and returned to New Annan.

When Anna turned 16, Ingalls approached her again, and found her resolve beginning to weaken. Her experiences in Truro had shown Anna that a normal life would never be possible for her, and at least Barnum's offer would allow her to pursue her education while earning a good living at the same time. It took one more visit from Ingalls to seal the deal, but this time Anna accepted. In 1862, she and her mother moved to New York.

Barnum paid Anna a generous wage to exhibit herself at his American Museum on the corner of Broadway and Ann Street, near City Hall. Her remuneration package at the museum included $23 a week in gold, plus comfortable lodgings, the finest clothes, a private tutor, provision for her mother to stay in New York and occasional trips to Nova Scotia and back. Anna also received singing, acting and piano lessons. Anna's mother stayed with her in New York for the first 12 months and then, seeing her daughter was in good hands, returned home.

Barnum advertised Anna as “The Tallest Girl in the World”, and had a spectacular dress made for her using 100 yards of satin and 50 yards of lace. The wily old showman had her pile her hair on top of her head to achieve an extra inch or so, and stressed Anna's size in publicity photos by posing her next to one of his many dwarves. Anna's peak height, recorded at about this time with Barnum's chosen hair-do in place, was 8' 1”.

Barnum soon realised that Anna was wasted in the minor room where he first placed her, and promoted her to the museum's grand hall, where she would play piano, lecture on giants in history or pose in classical tableaux. On at least one occasion, she played Lady Macbeth. As the world's only known giantess, Anna pulled in enormous crowds. “She was an intelligent and by no means ill-looking girl,” Barnum wrote. “During the long period when she was in my employ, she was visited by thousands of persons.”

Every now and then, Barnum would publicise the museum by sending Anna out on a carriage ride round New York. The giant carriage he built for this purpose was drawn by two huge Clydesdales, and drew such attention that crowds often followed it all the way back to Barnum's door, where box office staff waited to take their money.

Other attractions at the museum during Anna's time there included two male giants, Monsieur Bihin and Colonel Goshen, who were jealous of one another and would often fight. Tom Thumb (2' 5”) and his wife Lavinia (2' 8”) were also there, and Anna became good friends with the couple. All the performers lived at the museum, where they were expected to share a communal kitchen and living room, which had to be furnished to accommodate everyone from giants and fat ladies to living skeletons and dwarves.

In July 1865, Anna was trapped on the museum's third floor when a terrible fire broke out there. She was too big to escape through the window, the stairwell was filled with flames, and she feared the weakened stairs would not support her weight. The staff eventually got her out by commandeering a nearby derrick, smashing away the wall around the window to enlarge its opening and lowering Anna to the ground by block and tackle.

“The giant girl, Anna Swan, was rescued with the utmost difficulty,” the New York Tribune reported. “A portion of the wall was broken off on each side of the window, the strong tackle was got in readiness, the tall woman was made fast to one end and swung over the heads of the people in the street, with 18 men grasping the other extremity of the line, and lowered down from the third storey amid enthusiastic applause” (13).

“The giant girl, Anna Swan, was rescued with the utmost difficulty,” the New York Tribune reported. “A portion of the wall was broken off on each side of the window, the strong tackle was got in readiness, the tall woman was made fast to one end and swung over the heads of the people in the street, with 18 men grasping the other extremity of the line, and lowered down from the third storey amid enthusiastic applause” (13).

The animals at the museum - lions, kangaroos, bears, tigers - were not so lucky. Those unable to escape into the streets of New York either turned on each other or died horribly in their enclosures. The Tribune estimated that 40,000 people gathered outside the museum to watch it burn and see the bedlam all around it. “Barnum's was always popular,” the paper said. “But it never drew so vast a crowd before.”

The fire cost Anna $1,200 in gold from her savings, plus a substantial sum in cash and most of her other belongings. Barnum sent her home to New Annan to rest while he set about building a replacement venue. In September 1865, Anna returned to New York with an improved contract at Barnum's new American Museum, giving her 10% commission on the sale of all photographs, souvenirs and books carrying her likeness.

Anna hadn't been back in New York long when Barnum's new building was destroyed by a fire of its own in March 1868. This time, the panicking animals woke his stars quickly enough for them to adjourn across the street to an all-night tavern and wait for the fire department there. They were fighting another blaze already, and so took an hour to arrive at Barnum's, by which time they found that night was so cold the water froze in their hosepipes and the building was lost. We know some of the animals escaped this time, because a New York cop later shot a tiger he found stalking round the streets.

Anna had to work while reconstruction continued again, but knew her contract meant she'd have to pay Barnum a hefty royalty for any performances outside Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. In October 1868, she set off to tour the Nova Scotia towns of Albian Mines, Amherst and New Glasgow with a 3' 6" Scottish dwarf called Robert Bruce Jr as her support act.

As part of the show, Anna would wrap a tape measure round her waist, and then invite a woman in the audience to do the same. The length of tape required to circle Anna's waist just once would go three times round the average woman's waist. She was internationally famous by now, and drew big crowds everywhere she went. At one stop of the tour, people followed her to milliners, where they were amused to see Anna sit down while the assistant stood on another chair behind her to adjust the hat she'd chosen.

Anna was back with Barnum's operation in time for the 1869 US shows which led to her first meeting with Martin, then had Barnum book her on an eight-month European tour. A London diarist called Arthur Munby paid a shilling to attend her reception at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly on March 15 that year. “She sat like a Colossos among the crowd, taller by a head than the men who stood around her; and when she rose there seemed no end of the rising,” he wrote. “I looked up at her and spoke to her with great interest. Even thus, it seemed, one might speak with some creature of a larger species from another world; not human, yet belonging to a like grade of being” (14).

The British Library has a poster advertising Anna at the Egyptian Hall in what may well be the same show (15). This shows her as a solo act, billed "The Largest Woman in the World" and headlining above Chang and Eng, the original Siamese twins. The twins were big stars in Victorian London, and it's a measure of Anna's drawing power that she could force them from the top of the bill. Just two years later, she'd return as part of a double act with her equally impressive husband, and put even that fame in the shade.

Martin and Anna left England for the last time on July 2, 1874, sailing to Nova Scotia. They spent some time with Anna's family in New Annan, where a ten-year-old girl joined the crowd outside their house. "They came out and mingled among the people in a very friendly manner," she later remembered. “When they returned to the house, not only did they have to stoop to get inside, but they had to turn sideways as well.”

The next stop was Seville in Ohio, where Martin bought 120 acres of prime farmland. Anna had been diagnosed with consumption by this time, and they hoped Seville's lakeside site would help her condition.

The Bates' stay in Europe had been a lucrative one, and they arrived in Seville with a lot of money to spend. They set about designing a custom-built house where everything could suit their size and engaged local builders to begin work. The house, built from yellow pine on a timber frame, was completed in 1876. It had 14-foot ceilings, 8½-foot doors and giant furniture for Martin and Anna's use. After a lifetime of frustration at living in a world where everything seemed built to three-quarters scale, they finally had a home which suited their own bodies.

Lee Cavin describes the house in his 1959 book There Were Giants on the Earth! “From a side view, the house seemed to be built in stair steps,” he writes. “The front portion, with high ceilings, doors and windows was for the use of Captain and Mrs Bates. It had two side entrance doors and a porch across the front. An open stairway and fireplaces with mantels of imported marble graced this portion. Sliding doors between rooms were panelled in rare woods. Toward the back, the house, which was in four sections, each nearly square, dropped in height. Local explanation for this was that rear portions were used exclusively by servants, and Captain Bates saw no need to waste ceiling space on people who didn't need it” (16).

Martin, who had supervised the construction personally, stocked the surrounding farm with Percheron horse and shorthorn cattle. The carriage he and Anna had built was pulled by two huge Clydesdales, each 18 hands high. In the winter, they pulled the couple's sleigh instead.

The Bates threw a housewarming party, staged in the giant section of the house, but found that none of their female guests would risk trying to tackle the out-size furniture. Victorian ladies valued their dignity, and the prospect of showing their knickers while clambering on or off a giant chair was too terrible to contemplate. Anna's sister Maggie would often visit the Seville farm in later years, but always had to endure Martin's teasing as she struggled to cope with the place. “The furniture was all built to order,” Martin writes in The Kentucky River Giant, “and to see our guests make use of it recalls most forcibly the good Dean Swift's traveller in the land of Brobdingnag.”

The Bates threw a housewarming party, staged in the giant section of the house, but found that none of their female guests would risk trying to tackle the out-size furniture. Victorian ladies valued their dignity, and the prospect of showing their knickers while clambering on or off a giant chair was too terrible to contemplate. Anna's sister Maggie would often visit the Seville farm in later years, but always had to endure Martin's teasing as she struggled to cope with the place. “The furniture was all built to order,” Martin writes in The Kentucky River Giant, “and to see our guests make use of it recalls most forcibly the good Dean Swift's traveller in the land of Brobdingnag.”

Old friends from the circus and sideshow world would sometimes visit the farm too, including The Living Skeleton, Millie-Christine, Tom Thumb and his wife Lavinia. Martin and Anna picked up the Thumbs from the railway station on one trip, but the ever-competitive Martin got into a carriage race with one of his neighbours on the way back. As they hurtled down the rough country road, tiny Lavinia was nearly bounced into the hedgerow before Anna could make Martin slow down. On another visit, one elderly Seville resident remembered, he saw Tom Thumb sitting beside Anna in the carriage “like a doll resting on the seat”.

James Craven, a former animal trainer with Barnum's operation, owned a circus menagerie just west of Seville, and would sometimes give Martin and Anna one of his surplus animals. In this way, they acquired a boa constrictor and a monkey called Buttons, which Anna adopted as her pet. Buttons was kept on a chain at the centre of the circular lawn dividing the Bates' twin driveways, where he amused himself by throwing things at the staff. Not to be outdone, Martin installed a parrot on the front porch which he trained to screech “Get off my property” at a hated neighbour.

Martin's construction work did not stop at their own property. A single service crammed into a standard pew at Seville's First Baptist Church prompted him to commission a giant replacement, which he told the carpenter to finish by the following Sunday. When it became clear this deadline wouldn't be met, Martin kicked at the carpenter, who grabbed the protruding foot and propped it on to his shoulder. This left Martin hopping helplessly on one leg until the man released him and ran away. Martin got his special pew in the end, but not without having to find a replacement carpenter first.

This incident was a rare come-uppance for Martin, who seemed to become more bad-tempered as he got older, and more inclined to bully anyone who crossed him. He was walking with a cane by this time, which he sometimes used to hit people who displeased him. He also took to wearing his old Confederate uniform around Seville, hoping to provoke a reaction from someone. On one occasion, he got into an argument with two men at the town's barber shop and ended up fighting them both simultaneously.

Dale Swan, Anna's great grand-nephew, sums up Martin as “a gruff, argumentative man”, while one of Cavin's Seville interviewees calls him “a man of violent temper”. But he had his kinder side too. After church each Sunday, local children would cluster round Martin to hear the giant watch Victoria had given him chime the hour, or climb him like a tree to get at the sweets he kept for them in his pockets. When a toddler called Mable Mapledoram got restless during the service one morning, Martin soothed her by holding his watch against her ear until the ticking sent her to sleep.

Another little girl called Elgia Ogilvie was walking home after an errand at the Bates' house one day when Martin, driving his team hard, swept up the narrow road behind her and sent her scurrying into the ditch. She clambered out, her clothes ruined, and was so angry that she started shouting after the departing rig and throwing stones at it. Surprised, Martin returned to apologise, helped her on to the seat beside him and gave her a lift home. She arrived disarrayed, but triumphant.

Anna led a far quieter life in Seville than her husband. While Martin was kicking carpenters, brawling in barbershops or driving little girls into ditches, she occupied herself with quilting bees, where she told stories of her adventures round the world, and teaching at the local Sunday school. She always insisted that the farm's workers wash and smarten themselves up before sitting down to the evening meal.

Whatever the trials of having giants for your neighbours, most people in Seville seemed to regard Martin and Anna with affection, recalling in old age the times they had been allowed to sit in the giants' laps as children or proudly pointing visitors to the local dance floor which had collapsed when Martin and Anna cut a measure there. In 2006, the town staged its first annual Giant Fest, a three-day event in the couple's honour.

Things took a darker turn in 1878, when the couple found two years of non-stop building work had exhausted their savings. Martin had made matters worse by agreeing to lend money to several local enterprises, where he became a silent partner, but may never have seen any return. He's known to have launched several lawsuits over business matters too, which suggests that many of these loans proved ill-advised, and that Martin was not the shrewd businessman he imagined himself to be.

Just two years earlier, Martin had been rich enough to present a handful of diamonds to anyone he wanted to impress, but now he and his wife needed to start earning again. They signed up for a tour headlining with the WW Cole Circus, where a specially chartered train took them round the mining towns of the American West.

This was 1878, remember, and the American West was still very wild indeed. The real Al Swearengen - played by Ian McShane in the HBO series Deadwood - opened his Gem saloon there in April 1877, going on to run the prostitution and opium trades in a mining town every bit as squalid and lawless as the TV series depicts. Wild Bill Hickok had died only in 1876, Jesse James survived until 1882, and the indian wars lasted till 1890.

Cole's circus pushed into each new territory as soon as a railway line was laid to take it there, and was often the first professional entertainment the town had ever seen. Many of the towns Martin and Anna visited during this phase of their careers must have been just as rough as Deadwood, and a very far cry from the European palaces they'd frequented seven years before.

Back in Seville, Anna entered 1879 preparing for the birth of her second child. She began a hellish labour on January 15, attended by AP Beach, the small but dapper local doctor. When Anna's waters broke, she produced an estimated six gallons of fluid, and Beach called in his colleague Dr Robinson for help.

As the labour progressed, Beach and Robinson found the baby's head was too big to fit their forceps around it, and so they were forced to help him emerge by pulling at a strong bandage placed round his neck. The 22lb baby boy who appeared in the early hours of January 19, died after just 11 hours and was never named. His gravestone reads only “Babe”. Contemporary models of the child, sculpted with an average baby for comparison, make Babe look like a toddler holding his infant brother. “He was 28” tall, weighed 22lbs and was perfect in every respect,” Martin later wrote. “He looked at birth like an ordinary child of six months” (11).

Martin and Anna embarked on a second tour with Cole's circus later that year, partly to distract Anna from the pain of losing a second child, but they would never tour again. Their last public appearance together came in 1882 at the Barnum and Bailey Spectacular in Cleveland, where old friends remarked how thin and pale Anna was looking. On August 5, 1888, she died peacefully of heart failure, brought on by the consumption she'd suffered since 1874. It was the day before her 42nd birthday.

Anna left an estate of $40,000, willing $500 of this to each of her parents and $1,250 to each of her six surviving siblings. Martin commissioned a suitable coffin for her from a Cleveland company, sending them the required measurements by telegram. Unfortunately, the company decided these dimensions must be a mistake and delivered a standard coffin instead. It took Martin an agonising three days to get the proper casket made up and delivered, and he never forgot this experience.

The funeral, watched by a large crowd, was conducted on the veranda of Martin and Anna's house, and she was buried at Seville's Mound Hill Cemetery alongside her son. Martin had a 15-foot statue of a woman in Greek robes erected there, meaning it as a tribute to Anna rather than a representation of her. His chosen inscription, from Psalm 17, read: “As for me, I will behold thy face in righteousness. I shall be satisfied when I awake with thy likeness.”

A memorial service for Anna was held at the Baptist church she and Martin had attended, and their customised pew there was draped in mourning cloth. A stand full of flowers was placed where Anna used to sit. The Seville Times obituary mentioned her inquiring mind and thirst for knowledge, adding: “Her knowledge of the world was wide and varied, a fact which added in no small degree to her ability to entertain and instruct.”

Martin married again 1900, this time to Lavonne Weatherby, the daughter of a Baptist minister, who stood just over five feet tall and was some 30 years his junior. Lavonne insisted they move out of the giants' house to a normal home in Seville's East Main Street. This building already had the high ceilings which Martin needed, but the bedroom had to be enlarged to fit his enormous bed. The old house in Seville was sold, and eventually demolished by a family who found it too expensive to heat and maintain.

It was around this time that Martin - no doubt remembering his problems with Anna's coffin - commissioned a giant casket for himself and had it brought to Seville by train. A neighbour agreed to store it in his barn until it was required. That day came on January 19, 1919, when Martin succumbed to kidney failure at the age of 81. He was buried next to Anna, but not before enduring a somewhat disorderly funeral.

Finding the casket was too long to fit properly inside his hearse, the undertaker padded the end against any damage, and left it poking out from the hearse's rear door. It was feared the six pallbearers Martin had named in his will would not be strong enough for the task, so eight younger men were recruited to replace them. The six original nominees flanked the coffin as a honour guard instead.

And so the second of two truly remarkable lives came to its end. Few people remember Martin and Anna Bates today, let alone their wedding ceremony in the heart of Victorian London. For anyone who knows their story, though, it's impossible to pass through Trafalgar Square or glance up at St Martin's church without giving them a thought. Raise a glass to them next time you're there - and make it a tall one.

For a selection of Martin and Anna photographs, see http://phreeque.tripod.com/bates.html

Appendix I: The two-headed nightingale

Millie-Christine played only a supporting role at Martin and Anna's wedding, but effortlessly outshone the giants at their first UK press conference.

When the twins arrived in Liverpool in May 1871, the Daily Post called them "the most attractive feature of the new exhibition", and the Daily Courier "the most singular and psychologically-interesting member of the party". For the Liverpool Leader's man, it was love at first sight. "She has you on both sides," he wrote. "If you remove your head from one position, you are immediately the victim of another pair of eyes which fix you and, in fact, transfix you" (17).

You can see his point. Millie and Christine McKoy were just as refined and charming as Martin or Anna, but had made an infinitely more difficult journey to get where they were. Born into slavery in 1851, and tightly joined together at the base of their spines, the twins changed hands as property four times before their sixth birthday.

Only one of their owners showed the girls any kindness, but that was enough for them to begin the long climb from wretched poverty to worldwide fame.

The girls' parents were Jacob and Monemia McKay, two black slaves owned by Jabez McKay in Welches Creek, North Carolina. Jabez sold them to a showman called John Pervis for $1,000 when they were just ten months old. At first, McKay retained a 25% share of the profits Pervis earned from exhibiting the twins, but later gave this up for another $200 in cash (18).

Pervis sold the girls on to another showman called Brower, who'd borrowed his own funds from Joseph Pearson Smith, a North Carolina merchant (19). Somewhere along the way, their surname switched vowels to become "McKoy".

Brower took the twins to New Orleans, where a Texas con-man swindled them away from him in a fraudulent land deal and fled with the twins in tow. Without his star attraction, Brower had no way of repaying the loan, so Smith called in his collateral and found himself the girls' new owner - even if he didn't know where they were.

Smith hired a private detective to track the twins down, who followed a trail through Philadelphia and New York before discovering they were no longer in America. By now, it was 1855, and they were owned by William Millar, who was showing them in England. Millar's former partner, William Thompson, was also chasing the twins, claiming Millar had stolen them from him in Philadelphia.

Smith knew that an English court would not recognise any claim of ownership to the girls, but hoped it might rule that they should be returned to their mother. With this in mind, he purchased Jacob and Monemia from Jabez McKay and took Monemia to England with him. It's true that Millie and Christine represented a considerable investment for Smith, but he seems mostly to have been motivated by genuine kindness of heart and a desire to reunite their family.

Smith persuaded the Birmingham police to help him and Monemia grab the twins in a dramatic scene at the city's Exchange Rooms show, and won the following court case arguing they should be returned to Monemia's custody. After a brief period trying to work with the treacherous Millar, he spirited mother and daughters off to Liverpool docks and took them back to North Carolina, arriving there in 1857 or 1858.

Smith and his wife set about educating the girls, teaching them to read, write, sing, play piano and speak five languages. Simply by teaching slaves to read and write, they were breaking the law, and the girls never forgot Joseph's great kindness. "He seemed to us a father," they wrote in an 1868 promotional booklet. "He was urbane, generous, patient-bearing and beloved by all" (20). They were equally fond of Joseph's wife. "We can trust her," they said. "And, what is more, we feel grateful to her and regard her with true filial affection."

In 1862, Joseph died, willing Millie-Christine and Monemia to his son, Joseph Jr. His father's death meant the family needed to start earning money again, so Joseph resumed the girls' showbiz career, this time ensuring they received a fair share of all the money they made.

When the end of the Civil War made them free women in 1865, Millie and Christine began sending money back to Jacob, their birth father, who used it to buy Welches Creek land. By 1871, HP Ingalls' British promotional literature was claiming Jacob now owned the plantation where he and his daughters were born.

It was also during their UK tour with Martin and Anna that Ingalls first coined the twins' "Two-headed Nightingale" billing. This was designed to capitalise on the popularity of Jenny Lind, a recently-retired soprano known as "The Swedish Nightingale". Lind was still remembered very fondly in England, and any link with her - however vague - could only boost the box office receipts.

On June 24, 1871 - just three week's after Martin and Anna's appearance - Millie-Christine had a Royal Command of her own. Queen Victoria noted the occasion in her journal. “Directly after breakfast, went down with the children to see an extraordinary object, far more extraordinary than the Siamese twins,” she wrote. “A two-headed girl, or rather two girls, yet one, joined together by a sort of bar of flesh. [...] It is one of the most remarkable phenomena possible. They are very dark-coloured, if not exactly negro, and look very merry and happy. They sang duets with clear, fine voices”.

Any reference to “the Siamese twins” at that time meant Chang and Eng, the first couple to use that billing. Victoria was not alone in preferring Millie-Christine, who most people agreed was more cheerful than the sometimes sour Chang and Eng, as well as more fluid in her movements. The girls had learned to co-ordinate their four legs well, incorporating a few dance numbers into their act, and never seemed to feel sorry for themselves. “Although we speak in the plural, we feel as but one person,” they wrote in 1868. “We would not wish to be severed, even if science could effect a separation. We are contented with our lot, and happy as the day is long” (20).

When the Bates left for the continent in 1872, Millie-Christine stayed on in London, appearing at the Agricultural Hall, the South London Palace and the Standard Theatre. After a family holiday with the Smiths in Brighton, where they visited the Royal Pavilion, Millie-Christine and Joseph Jr left for Vienna to begin her own European tour. They were back in London for an 1875 show at St James's Hall. “She sings beautifully,” the poster declared. “She dances elegantly, talks with two persons on different subjects at the same time, and excites the wonder and admiration of all beholders” (21).

Millie-Christine held a farewell tour of England in 1885, and then returned to Welches Creek where the girls bought a small farm and funded a school for North Carolina's black children. She must have continued touring in the US for a few years, because we have a string of memos from bemused railway officials all over America wondering whether she should be charged for one ticket or two.

Joseph Jr, who was travelling with Millie-Christine at the time, was quick to claim a refund whenever an extra ticket was demanded, and most of the railway companies let him have his way. "Millie-Christine, the dual woman, is transported over these lines for one ticket," HM Emerson of the Atlantic Coast Line told his conductors. "Not withstanding the fact that she has two heads" (22).

After a fire in 1909, which destroyed most of their possessions, Millie started to show signs of TB. She'd always been the weaker of the two sisters and died three years later, on October 8, 1912. Christine survived her by just 17 hours. They were 61 years old.

Millie-Christine's joint remains have recently been exhumed from what had become an endangered site and given an honoured spot in Welches Creek Cemetery, where the town has named a nearby road after her (23). The sisters' original inscription, now replaced with two brief biographical sketches, read: "A soul with two thoughts. Two hearts that beat as one."

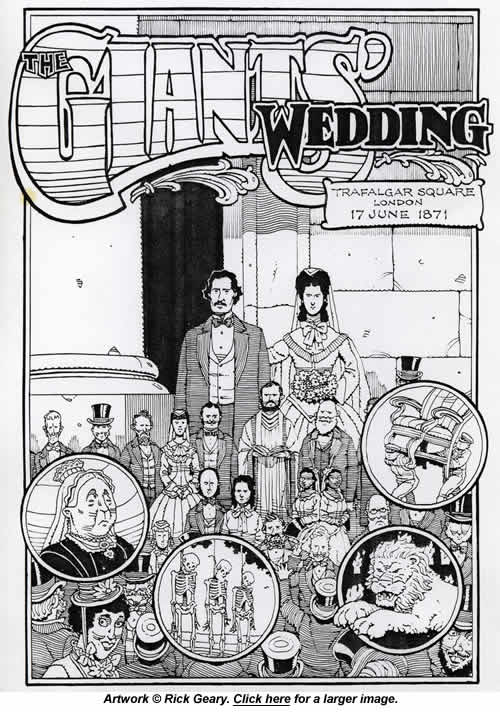

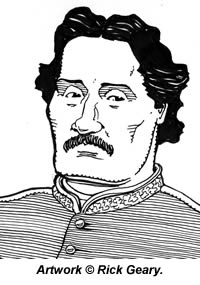

Appendix II: Rick Geary's artwork for this piece

I first stumbled across Martin and Anna's story in 2004 as a single sentence in a book of London walks, and set about researching it just for my own interest. As I found out more and more about them, it struck me that the many dramatic visual elements of their story - the wedding, the Barnum fire, the Kentucky lynching - would make it ideal material for a graphic novel. As soon as that idea came to me, I knew Rick Geary would be the perfect artist.

Rick's an American cartoonist whose work I've loved ever since I first saw it in National Lampoon back in the 1980s. In 2007, he completed a nine-volume series of graphic novels under the umbrella title A Treasury of Victorian Murder. Each of these meticulously-researched books tells the story of a different 19th Century killing, from the London Ripper murders to Lizzie Borden's double parricide and Abraham Lincoln's assassination. Rick's made the Victorian era something of a speciality, and always draws its characters and their world with great wit and charm.

I sent Rick a copy of all my Martin and Anna research in early 2006 and suggested we pitch the idea round a few publishers. Just as I'd hoped, he found their story fascinating too, and confirmed it was just the sort of subject he liked to tackle. As ever, though, he was very busy, and had several other projects that would have to be completed first. The ball was in my court.

You could buy $2 for every £1 then, which let me commission Rick to produce the sample splash page and the two portraits you see here. I framed the originals for my wall and started sending out photocopies and a synopsis to what I hoped were the most likely publishers.

Of course, all that was before the Credit Crunch hit, so Lord knows whether the project will ever come to anything. In the meantime, we have the drawings here to savour, which Rick was kind enough to say I could reproduce on my site.

Sources

1) Daily Telegraph, June 19, 1871.

2) Liverpool Daily Courier, May 1871.

3) Liverpool Daily Post, May 1871.

4) Anna Swan: Nova Scotia's Remarkable Giantess

(http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/205/301/ic/cdc/aswan/storyindex.htm)

5) Harper's Bazaar, July 29, 1871.

6) This is the birth date shown on Martin's grave marker (see http://www.findagrave.com), and it's the one I've used in all my age calculations. Martin's autobiography gives his year of birth as 1845.

7) The Giant of the Hills: Martin van Buren Bates, Tennessee Independent Herald, August 5, 1993.

8) The Rest of the Story About the Civil War Giant, by Bruce Bates, FNB Chronicles, Spring 1998

(http://www.tngenweb.org/scott/fnb_v9n3_giant.htm)

9) The various sources contradict one another on the details of Martin's military career, so I've put together the most logical sequence I can from the available information.

10) The Giant of Letcher County, by Burdine Webb, reprinted in The Kentucky Explorer, June 2005.

11) The Kentucky Giant, by Martin van Buren Bates (Lulu, 2005).

12) Anna Swan, by Mary M Alward

(http://www.suite101.com/article.cfm/biographies/100546)

13) New York Tribune, July 14, 1865.

14) A Dictionary of Victorian London, ed. Lee Jackson (Anthem Press, 2006).

15) British Library catalogue.

(http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/evanion/Record.aspx?EvanID=024-000001830&ImageIndex=0)

16) There Were Giants on the Earth! by Lee Cavin (Saville Chronicle, 1959).

17) Liverpool Leader, May 1871.

18) Mark Gilchrist, Whiteville News Reporter, October 2008.

19) Millie-Christine: Fearfully and Wonderfully Made, by Joanne Martell (John F Blair, 2000).

20) The History of the Carolina Twins, by “one of them” (Buffalo Couruier Printing House, 1868).

21) British Library Catalogue

(http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/evanion/Record.aspx?EvanID=024-000001773&ImageIndex=0)

22) Biographical Sketch of Millie Christine, the Carolina Twin. Surnamed the Two-Headed Nightingale and the Eighth Wonder of the World (Hennegan & Co, circa 1909).

23) Find a Grave