There's a LOT of exclusive material in my book which appears nowhere on PlanetSlade. If you haven't read it yet, please click on the cover to buy a copy.

In the meantime, feel free to enjoy the following little gems from the book's out-takes.

These are the anecdotes, quotes and sidebar stories I'd have dearly loved to include in the book but which its finite page count just wouldn't allow. Think of them as my equivalent of the deleted scenes, star interviews and bonus features you'd find adorning your favourite DVD boxed set.

Menu

1) Songs

Billy Bragg, Laura Cantrell, Dave Alvin, Rennie Sparks and other leading musicians continue our discussion of their favourite murder ballads. These comments from the book's interviews are the "leftovers" I couldn't bear to waste.

2) Questions

How did you discover murder ballads? Why do we love them so? I asked my interviewees far too many questions for all their answers to fit in the book. These are some of the replies that got squeezed out.

3) Digressions

Other stuff came up too. Includes Jon Langford on putting together The Executioner's Last Songs project, Mick Harvey on the Bad Seeds' studio habits and Dave Alvin on killer bees.

4) Postscripts

Every chapter's research uncovered sidebar stories I had no space to include in the book. Meet Charlie Lawson's killer cousin, see how Winston's sheriff was attacked for failing to catch Ellen Smith's killer and join me on a trip to Tom Dula's grave.

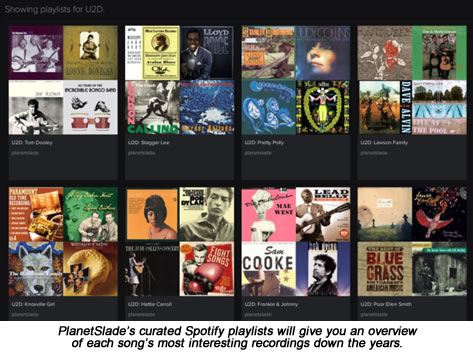

5) Playlists

I've put together a set of eight carefully-curated Spotify playlists to go with the book, each one carefully selecting the most interesting recordings of their chosen song down the decades. See below for all the links.

Bonus 1: Songs

These comments

from the book's

interviews are the

"leftovers" I couldn't

bear to waste.

Stagger Lee:

"One of the greatest. That is the bad boy of bad boy songs." - Dave Alvin.

"For Stagger Lee, I originally had a descending guitar riff like The Stooges' I Wanna Be Your Dog. I still perform it that way sometimes and it works! Whether Stagger Lee and Billy were black or white, young or old, has always been a choice. These songs survive through interpretation: there's no one true version. Depending on the version you're listening to, it could be a tale of vengeance or one of blind cruelty. In my telling of Stagger Lee, he goes too far in a moment of extreme arrogance and ends up in a living hell. - Anna Domino, Snakefarm.

"It was one of the last songs recorded for the record. I knew some sort of bluesy versions, but it's not a song I was overly familiar with. Nick [Cave] had the idea of Marty playing a bass riff that was inspired by The Geto Boys - a really extreme rap group of the 1990s. It just kind of came together." - Mick Harvey, The Bad Seeds.

Frankie & Johnny:

"Stagger Lee, Frankie & Johnny, Delia, they all come from the same era - end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century - when things were transitioning from rural to semi-industrial. The ruthlessness and rootlessness: these were songs of a community in transition. Separated from your home, separated from your family. These are the things that happen when you leave home and leave the simple life." - Dave Alvin.

"Frankie & Johnny was a song I grew up with, so it was a natural to record. We shot short movies for every song before we went on tour [and] I wish I could show you the footage for this song. It was all shot in an old art deco hotel in San Francisco. The camera staggers down a long, dim hallway going in and out of focus and shuddering like someone on their last legs: on drugs, dying or dreaming. Close to oblivion. The moment just before sleep. This is what I was trying to capture in some way." - Anna Domino.

Knoxville Girl:

"Over the decades, verses were discarded so you tend to get these songs - Knoxville Girl being one of them - where, after years and years of editing, you get it down to these crystallised verses that say so much and say very little at the same time. You can read into it just about whatever you want." - Dave Alvin.

"My parents met in Knoxville. It's weird, there's a bit of pride [in the song being set there]. Like all these songs, it has its brutality to it. It feels like it's remade from an older song - that kind of ancient quality to it. That's what comes to mind there." - Laura Cantrell.

"I was given a Louvin Brothers album by a friend in New York in the 1980s, just after I'd gone into this voyage of discovery into classic honky-tonk music. It was Tragic Songs of Life, and Knoxville Girl's on that. It was recorded in the 1950s, probably in Nashville, but it just seemed to be ancient. It's a very timeless sort of story, but not fully explained, and so mysterious. All he tells you is how he loves her, then he beats her to the ground and chucks her in the river. It's like, 'OK, everyone in America's some kind of psychopath who just randomly kills people'." - Jon Langford, The Mekons.

"I've always been a writer and a reader, but had never considered song lyrics could have such power before hearing murder ballads. Knoxville Girl showed me how I could write lyrics. It gave me a way inward." - Rennie Sparks, The Handsome Family.

"I like The Louvin Brothers' version too, but I thought Dad and Carter really knocked it out of the park." - Ralph Stanley II.

The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll:

"That's a gorgeous song. The masterful way Dylan tells the story is pitch-perfect. It's one of the songs from that era that that he still does. I did about 13, 14 shows with him in 1999. We were doing Chicago, New York, Toronto, big cities like that, and he did it just about every night." - Dave Alvin.

"I think it would have to be in the top 20 songs of Dylan's pre-electric period. I would put it in the top tier of those early songs. It puts him right there in the folk tradition, and you can see why people like Pete Seeger thought so highly of him. When you set something - a song, a story - in the tradition, it makes you realise that people have fought these fights before. I think that does help. It sounds in the space where people have those kind of folk memories." - Billy Bragg.

"That is a devastating song. It could be a film. It's got all the setting of the scene, the drawing of the characters, the emphasis on William Zantzinger - really showing this casual brutality and senselessness. It's a tough song, but like any great story it's hard to turn away from it when you hear it. It's crafted so well that you can't look away. You have to hang with it through to the end." - Laura Cantrell.

"Tom [Brosseau] brought Hattie Carroll to my attention one afternoon when we were working up songs. He had a tome of Dylan's lyrics on his shelf, and when he opened the page to Hattie Carroll I thought 'Hell's Bells, this song is a wordy bastard'. But the cadence of the tongue-twisting melody soon became my favourite part of the song." - Angela Correa, Les Shelleys.

Tom Dooley:

"My association with it is not as a murder ballad, but as a pop phenomenon. I think right away of The Kingston Trio and those sweaters - a murder ballad becoming a pop song in that era. I don't want to take The Kingston Trio to task for making a jaunty melody out of it, but it's not a song that's been able to outrun that ubiquitous version of it." - Laura Cantrell.

"Tony Fitzpatrick's kid was in the studio when we recorded that, and Steve [Earle] told him every time he swore he'd give the kid a dollar. At one point, Steve shouted, 'Fuck me in the dick!', and the kid was sitting there looking at his hands, counting up how much money he was going to get." - Jon Langford.

"We never called ourselves folk singers: I just think of it as a song. We considered ourselves professional entertainers. In the first year of the Grammies, they didn't have a folk singing category, so they looked around and realised the closest thing to it was country & western. Country music was at a low at the time, so they thought giving us a Grammy for Tom Dooley would help it out - which it did. That saved country music, because it was dead in '57 and '58." - Bob Shane, The Kingston Trio.

Pretty Polly:

"I love that song. The Sadies play that live quite a lot. It's almost taunting, that song, isn't it?" - Jon Langford.

"There are many folk songs where dying people request their graves be long and wide, or green and clean, and I always think it's so strange to be making demands when you're dying. But it's even stranger to have a murderer considering the layout of his crime scene before he starts shedding blood." - Rennie Sparks.

"I've heard that song since I was two years old. Soon as I could focus on listening and paying attention, I guess. That was part of Dad's show every night. He recorded it again with Patty Loveless, and I was rhythm guitar man on that track. Everything just went smooth that day. The music, the singing was great, Patty was really into it. She loved Dad. It was just one of those moments in music that's hard to recreate in the studio sometimes - everything just went like clockwork." - Ralph Stanley II.

Poor Ellen Smith:

"There's this hypocrisy in the words. Peter DeGraff is feeling horrible and lonely and hoping God understands him, [but] when Ellen's mentioned she's 'shot through the heart lying dead on the ground'. Her humanity tends to get put in a box labelled 'victim' because it's a little disturbing to go past that. I kind of enjoyed that aspect of it, but you can't tackle it as singer other than to play it very straight." - Laura Cantrell.

"There are certain songs have a more universal feel to them than others. In The Pines, a song like that, could be taking place anywhere, in any time, any culture almost. Whereas Banks of the Ohio has a specificity to it that defines it more to a time and place. Poor Ellen Smith, though it's a very popular version of this kind of song, doesn't feel like a very universal song to me. It's a universal story, but set in a very specific time and place." - Laura Cantrell.

"We didn't record it the way Molly O'Day or The Stanley Brothers would have, we used a little more studio craft. Kenny Kosek, who played fiddle, couldn't be with us when we did the basic track, so he came in after. We tried different things, made him play it five different ways, and might have used bits from all five. So there was a little bit of that 21st Century licence to not go by just the performance in the room." - Laura Cantrell.

The Murder of the Lawson Family:

"The nature of pure folk music, whether it's Delta blues or murder ballads, is that it's music made for and by a community. These were people who lived day-to-day with death. If they wanted meat, they had to kill it themselves, skin it and cook it - so death was never far away. In our modern world, we try to keep death at a distance, but for these people, death and bloodshed was woven more into the fabric of life." - Dave Alvin.

"These are people that lived difficult lives, and the closing lines about the hope of going to a place of peace and love where there's no pain says a lot about the community where the song came from. I remember when we got to the 'peace and love' line there was a real moody feeling inside the studio." - Dave Alvin.

"In folk music, there's always the line beneath the line. There's what the song's saying and what the audience is actually hearing: 'We didn't need no lawyer for him'. In the same way, in blues music of the 1920s and 1930s, there was all sorts of commentary on injustice, but it was told underneath the lines." - Dave Alvin.

How did you discover murder ballads?

"My brother Phil and I were odd little kids. Our cousin Mike, he was what today would be called a folkie. He played banjo, he played guitar, so at an early age we were exposed to the music that he liked, which was Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Dave van Ronk, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, early Bob Dylan - that kind of stuff. We went on this educational thing, self-educating ourselves into American music. In those days, there weren't the number of reissue albums that there are today, so that meant only one thing: you had to go and find the old 78s." - Dave Alvin.

"A friend of mine at school had his Dad's copy of The Times They Are a-Changin' and I swopped it with him for my copy of The Jackson Five's Greatest Hits. We're talking about the early seventies here, so it was the middle of glam. I suppose it was a bit like kids ten years earlier hearing bluesmen for the first time. I hadn't really heard anything that was so raw and so visceral. It remains my favourite Dylan album to this day. There was something about the stories and the way they were told that really, really engaged me." - Billy Bragg.

"Songs like Poor Ellen Smith were so ubiquitous in bluegrass and in the folk era of the 1960s. For me, being southern, I'd heard a ton of bluegrass without ever actually going to a proper bluegrass festival, because it was around. It really was in the air." - Laura Cantrell.

"In college, a few close friends introduced me to Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music. That was the beginning of a love affair with old storytelling and traditional folk music. From some of my research, I discovered that old murder ballads and folk songs sometimes functioned as tales of caution in a time rooted in oral tradition. It was fascinating that details and names would change over time, and had even been brought to the States from overseas. All this coalesced into me spending all my time thinking about murder ballads when I was younger. It was strange and new territory at the time." - Angela Correa, Les Shelleys.

"[Murder ballads] were already in my head from family and from the folk revival of the '60s. At that time, all I wanted to play was T. Rex, but St James' Infirmary and all the other traditional ballads got mixed in. They all seemed to go together. I loved the ballads because they were compelling stories. I never did much narrative songwriting myself, but I recognise its power." - Anna Domino, Snakefarm.

"The holy trinity of country & western content to me was drinking, cheating and killing. I really liked the honky-tonk drinking songs and all the murder songs. There were murder songs in the charts right up to the '70s. Olivia Newton-John did Banks of The Ohio. That's a really dark song, but it's a big pop hit - it's fine. My grandma used to sing Delilah when I was a kid, and that's a vicious revenge ballad. I saw that tradition going right back through folk music, so I saw where those songs came from - the melodramatic life and death aspects of it all." - Jon Langford, The Mekons.

"Dad and Carter did murder ballads a lot - they had a lot of them. I heard a lot of their music when I was just a kid. Going on the road, I was with him a lot and I heard it there. My mother used to play The Stanley Brothers' records. Ballads are my favourite. If it was up to me, I could sing slow songs all night long. Something that tells a story." - Ralph Stanley II.

It's almost always a man killing a woman. Is this a misogynist genre?

"If you go back to the Child Ballads, there's this real theme of a man put on the spot by a woman who needs something from him. They've had a child, or she's with child or whatever - something that's going to ruin it all - and there's this desperation, trying to maintain your freedom." - Laura Cantrell.

"When I got into murder ballads I was enthralled by the stories, but felt like there was an entire side of the story missing - the voice of the victim. I felt so much empathy for the gals in the songs, going off with a suitor thinking he was perhaps about to declare his love, and instead getting killed off to avoid shame, scandal or inconvenience. That evolved into telling the other side of the tale in my own songs like Dear William, Sunrise Your Hanging Day and Painted Faces." - Angela Correa.

"Traditional music is meant to be cathartic, so suffering of the innocent looms large. One purpose of these songs was to warn the young of what would happen if they were careless. In many of these femicide songs, the murder is followed by deep regret. Not always, of course, but if you can find all 63 verses, it often makes an appearance." - Anna Domino.

"When you're killing someone in a song, you're not really killing them. Songs are like dreams. The women on those [Executioner's Last Songs] albums all wanted to do the nastiest and goriest ones possible." - Jon Langford.

"It's a mistake to think that art is experienced like reality. No sane woman wants to watch a man actually kill another woman, but art is about expressing deep, inexpressible fears and desires. It's not literal." - Rennie Sparks, The Handsome Family.

Why do we love murder ballads so?

"Murder ballads tend to deal with an unjust death and the better ones tell their story cryptically enough that you can read anything you want into it. Once you get past the macabre side of things that sucks some people in - 'It's a song about a guy that offed his family, man!' - then you get into whatever the strange truth of the song is. They describe the sadness and the pain of the world in three or four verses." - Dave Alvin.

"Maybe it's the same thing that makes us love ghost stories. They bring us close to something that's kind of inconceivable and would be difficult to experience in any other way. You wouldn't always want to be hearing such gory stories, but putting them in this format allows them to be assimilated in some way. I think we need to experience that some way or other and be able to express it." - Laura Cantrell.

"Murder ballads are just part of the American repertoire. There's a sort of pornography of sorrow, and it's always been thus. It's human nature to obsess over the things that frighten us." - Anna Domino.

"It's part of a cultural interest in the idea of murder in general which is quite hard to justify morally - much like light entertainment TV shows on the subject. It's a bizarre kind of anomaly in our culture. I can't quite explain it myself." - Mick Harvey, The Bad Seeds.

"I think it's a way of processing the dark fears we have. That's what I see these songs as doing: they're a way people can process stuff that they might not understand." - Jon Langford.

"It's very difficult to come to terms with our own mortality. These songs give us a way to hint at it: to tell the truth without actually telling it. We all know what we are saying to each other, even if we are unaware that we know." - Rennie Sparks.

Why is country music such a good fit for murder ballads?

"That forlorn thing of being ultimately separated from your home and the finality of it? That's something country music can communicate in a pretty straightforward, simple way - just by a few notes sometimes. People talk about the 'high lonesome' sound, and that applies very well to this kind of material. These songs are a good vehicle for that type of expression." - Laura Cantrell.

"Hard-core country music was trying to deal with reality, but it was kind of reality on steroids. It treats everyday life in a very direct, head-on manner. But it goes way beyond that. It revels in this tragedy - wallows in it. The way these songs process those fears and anxieties is very interesting, I think." - Jon Langford.

What are the challenges of playing murder ballads live?

"When you have an audience that's listening to the lyrics and you do a song like The Murder of The Lawson Family, it tends to take two or three songs to get the audience back. Because they will get into that mood. If you've got 'em listening and you do that kind of thing, you're affecting them, you're painting that picture in their brains and you've got to get them back somewhere else pretty quick." - Dave Alvin.

"I was playing [The Lonesome Death of Rachel Corrie] on that tour, when we were in America. It surprised a lot of people. I had to do a bit of explaining about it, because not everyone was familiar with the story. We were out in the mid-west and it hadn't made much news over there." - Billy Bragg.

"We were pretty careful not to put [Poor Ellen Smith] right up against Churches on The Interstate or another one of my songs that also has a train beat. It needs to be a little bit on its own. It would be a good one to come out of a really slow song, so you could build back up to a more electric moment - heading towards something that would be louder and with the drums." - Laura Cantrell.

"[The fact that Stagger Lee's become a fan favourite] is not necessarily a compliment. The bigger the concert, the more dumbed-down it gets. People can go 'Ah, this one'. It's an easy one for people to connect with - they know the words." - Mick Harvey.

Dave Alvin on killer bees:

"I have one problem. This sounds ridiculous, but it is true. On my property, I have a swarm of killer bees. There's a bee guy, he was supposed to be here at ten, which was about half hour ago and he contacted me to say he's going to be here at eleven. If during the interview I start talking to a bee guy, that's the reason. I seriously have killer bees swarmed into my yard.

"I looked out the window day before yesterday and I saw this strange movement that was almost like a funnel cloud. I was like, 'What the Hell is that?' - and it was bees. Fortunately, I know a guy who is a bee expert. I got a hold of him right away, and he was like, ' Oh Hell, you got killer bees. I'll be there Monday'."

Billy Bragg on rediscovering radical folk music in the UK miners' strike:

"I was aware of folk - I was listening to people like Shirley Collins and The Watersons before punk - but the thing about punk was, it kind of swept all that away. Going up and doing the gigs in the coal fields brought me into contact with people like Jock Purdon, and the songs he was singing were much more political than the songs I was singing.

"It was me, coming from my punk tradition, bumping up against what you might call the Bert Lloyd aspect of folk music, which I'd somehow missed. It reminded me that folk music has a strong political thread to it, so I doubled back and started reconnecting with that. That's kind of what led me to writing Between The Wars. I don't think I could have written that if I hadn't had a prior appreciation of the tradition.

"I think the thing folk and punk have in common, particularly with the folk revival in the UK having its roots in skiffle, is 'Here's three chords - now form a band'. Skiffle was very much like that, and so was punk."

Laura Cantrell on Molly O'Day:

"She was a banjo player, and if you hear her voice, she's probably the closest to Sara Carter of women singers of that era - very reminiscent of that Carter Family style. But she was a young woman and it would have felt very contemporary and energetic. She was active in the '40s, early '50s and then had a nervous breakdown and left the commercial music business behind.

"It's hard to remember sometimes when we listen to these old records that it was very young people making them, and they were doing them from gig to gig. You strip away the layers of our ideas about tradition, and they were basically kids, just playing music and trying to figure out how to make enough money.

"Pre-Kitty Wells, Molly was one of the more successful women in country music and recognised by the national recording establishment. She had a few hits. She recorded those early Hank Williams songs, some of which have language that sounds almost Victorian. She recorded Tramp on the Street and Six More Miles to the Graveyard. She made a bunch of recordings for Columbia and they were anthologised and repackaged over the years."

Mick Harvey on making The Bad Seeds' Murder Ballads album:

"We'd recorded Song of Joy, which is the opening track, in the sessions for the previous album, Let Love In. It didn't fit with that album somehow. We didn't finish the song: we'd recorded a basic track for it. Also, we were doing demos for Let Love In, and we recorded O'Malley's Bar in its entirety.

"O'Malley's Bar is one take. Nick re-did some of the singing that afternoon and he did a very long, complicated piano overdub on it, but the whole basic track is just one continuous take. Once we were on a roll with The Bad Seeds, it was four, five basic tracks a day. Once you're in the slot, you should be able to do that. You shouldn't be labouring over stuff. It's just about getting the right feeling going, and then it should be there.

"There was great interest in the album in preparation, which is something you don't normally have. The whole idea of it caught people's imagination. It was something people could latch on to as opposed to 'Oh here's a new batch of songs', which is always a bit indefinable. But when it's an album of murder ballads, it's something people can grab on to. I think they could imagine what it would be like, because it did somehow seem to fit with The Bad Seeds thing.

"Shane MacGowan came in [to Wessex Studios] and tried to get the band to do Boom Boom Out Go the Lights, that John Lee Hooker song, but we couldn't figure out what he was singing. He was trying to play guitar, and it was just totally confusing. It could have been genius, but somehow we couldn't quite get the communication going.

"Recording an album, we'd kind of wind up in a bubble and didn't have much of an idea what are the key songs. It's hard for us to be objective about it - it's kind of 'Well. This is just another weird album, maybe no-one will like it'. We were always surprised when people really liked what we'd done. Even the Kylie thing.

"When we recorded that song [Where The Wild Roses Grow], there was no intention it was going to be the single. It seemed like a weird kind of moody, slow, traditional ballad of sorts. It's certainly out of step with anything else that might have been a hit several years either side of it. It was just another one of the songs, you know? Much like Crow Jane, or one of those odder songs on the album. Even when Kylie got involved, it was 'Well, it can't be a hit single, can it?' The song was too weird."

[Where The Wild Roses Grow spent four weeks in the British charts, peaking at number 11, and scoring The Bad Seeds an appearance on Top of the Pops. "It was just some weird accident," Harvey told me. "It was pretty funny."]

Jon Langford on organising The Executioner's Last Songs project:

"It was a really hostile atmosphere. Bloodshot Records got a lot of death threats and anger. We had some fucking incredible mail from people: 'I thought Bloodshot was a shit-kickin' label, but now I realise you're just a bunch of pinkoes from the north'. I had a lot of stuff: 'Go back to Russia', and stuff like that. Quite fierce.

"There were some people who didn't want to do it. They wanted to be on the album because they thought it'd be cool, but they were pro-death penalty so they thought I might not want them. Each story was slightly different. It was a lot of me hi-jacking people - going to gigs and just kind of tramping in and making the suggestion. It didn't always work. I grabbed Billy Joe Shaver at a gig somewhere and tried to explain why this would be a good thing to do and he just looked at me like I was mental.

"Most of the musicians in the kind of sphere that I was operating in were just like, 'Right, that's fine, I get it.' I told Dave Alvin about it and he just said, 'OK, I'll fly in'. We got Bloodshot to pay for him to fly in, he rented a car, came to the studio and he just played all day. He played on all these different tracks and when we ran out of tracks for him to play on, he played on Dean from the Wacos solo album, he played on this Kevin Coyne album I was working on. He was just fantastic: 'I'm here to play, what do you want me to play?'

"Brett [Sparks] was worried that the guy didn't get hung at the end [of Knoxville Girl]. He thought that was some sort of criteria for the album - that everyone had to be hung. He ends up in a prison cell, doesn't he? Maybe it didn't quite fit, but I think it's dark enough."

"We just kept discovering songs. It was the volume of the stuff people would keep bringing to the table: 'Oh, aren't you going to do so-and-so?' And I'd never heard of that song! So it was a fabulous education to get from all these people who were fanatical about the history of country music. I like the fact that people were studying old country music, and taking things from it, but at the same time pushing it in a slightly different direction - a direction which mainstream country music had chosen to abandon."

[Langford launched The Executioners' Last Songs project to help raise funds for The Illinois Death Penalty Moratorium Project. Governor George Ryan's January 2000 moratorium was followed 11 years later by legislation abolishing executions throughout the state. "It was really gratifying," Langford told me.]

Department of Nothing Changes:

"We always made more money off of live performances than we did on records. In those days, you didn't get paid any big money on recordings. You got 2c on a play." - Bob Shane of The Kingston Trio on the music business in the 1960s.

"My Mom and Dad have some music service on their cable TV. Channel 1500 is bluegrass, or whatever. [.] My Dad bolted up out of bed and said 'They're playing Poor Ellen Smith!' It was my version of it. It's a nice thing for the parents, but I know of course that I'm getting paid exactly two pennies." - Laura Cantrell on the music business in the 2010s.

Bonus 4: Postscripts

The book's

research uncovered

many sidebar stories

I had no space

to include.

Here's a few of

my favourites.

Lawson Family: The OTHER Charlie Lawson

Shirry Madison, whose great-grandfather Samuel Hill conducted tours of the Lawsons' cabin back in the 1930s, passed on an intriguing bit of family lore when interviewed for A Christmas Family Tragedy. "[My grandparents] said there were two Charlie Lawsons in the family," she tells the documentary's director Matt Hodges. "There was Laughing Charlie and Loafing Charlie. Laughing Charlie's the one that killed his family."

Charles Davis Lawson, who inspired the ballad covered in my book, slaughtered his wife and six of their seven children on Christmas Day 1929 and then killed himself. The massacre took place in Stokes County, North Carolina, and made headline news from New York to California. That's Laughing Charlie, and his crime's been well-documented. But who was Loafing Charlie?

One candidate is Charles William Lawson, born just across the state line in Patrick County, Virginia, in 1893. Both Charlie Lawsons have a paternal line tracing back to Jonas Lawson (1756-1816) and both lived within a few miles of each other along the Virginia/North Carolina border for over 20 years. Both had a spell working in the West Virginia coalfields too, though never at the same time.

I hope that's all clear so far, because this is where it starts getting weird. Charles William Lawson murdered a close member of his own family at Christmas time too and did so less than 50 miles from the other Charlie Lawson's home in Walnut Cove. His crime filled the same newspapers which would report Fannie Lawson and her children's deaths 16 years later and his own demise was even more brutal than the Walnut Cove Charlie's suicide. He's worth a ballad all of his own, the first verse of which would place us in Virginia on New Year's Day 1914.

That's when people in the small community of Ararat noticed that a prosperous local tobacco farmer had gone missing. William Lawson's farm lay about eight-and-a-half miles north east of Mount Airy and was run with the help of his two sons Sam and Charlie, who were both about 20 years old. When queries were raised about their father's whereabouts, they and their mother said he'd left home on foot just before Christmas, telling them he was going "up on the mountain" to buy a sawmill and would be away for several days. He'd taken $50 with him for the purchase - a sum worth about $1,200 today. Hilliard Jessup, one of the family's neighbours, backed up their account, saying he'd seen William walking along the road near his home on the afternoon he vanished.

William was known to be a big drinker and his sons confirmed he'd been "somewhat under the influence of liquor" when he left the farm. At first people assumed he'd simply gone off on a bender and would return home whenever he felt like sobering up again. Another theory developed that he may have been trying to cross the nearby Dan River while drunk, fallen in and drowned. Still a third suggested he must have been killed by brigands for the cash he was carrying.

William's brother refused to swallow any of this, organising search parties to comb the surrounding area and firing off telegrams to anyone he thought William might have been visiting. The breakthrough came when another Ararat resident stepped forward to say he'd seen Sam and Charlie ploughing one of their father's fields in the early hours of Christmas Eve. He'd thought it odd at the time, not only because there was barely any light to work by, but also because the field was far too wet and mud-clumped for ploughing to do any good.

On January 16, Sam and Charlie joined the lines of men forming up in the field with pitchforks and sharpened sticks, which they used to test the ground every few feet as they moved slowly forward. One man jabbed his pitchfork into the ground and found the earth beneath the ploughed furrow was looser than the packed-down mud he'd expected to find. Drawing his fork out again, he noticed sub-soil mixed in with the top-soil, suggesting a hole had recently been dug there and filled in again.

"Everyone present at once began to gather about the spot," the Western Sentinel reported. "After digging down about two feet, one of the shovels struck the hand of the buried man. When the coroner arrived, he immediately ordered the body to be uncovered. The head was wrapped in six fertiliser sacks and a string tied around the neck held the sack over the head. The physicians who examined the body found the skull had been smashed into 15 pieces and gave as their opinion that he had been struck with an axe or sledgehammer." William had also been shot through the heart, which suggests the pounding his head received came in a spasm of excess hatred when he was already dead. (1)

The police immediately arrested Sam and Charlie, together with Jessup who it was now clear had deliberately lied in backing their story. Soon after, they decided they had enough evidence to hold only Charlie, so then other two were released. Charlie confessed to killing his father, explaining that it had all happened on December 23. William Lawson had come home drunk and attacked his wife with rock, the lad said. Charlie had acted to defend his mother in similar circumstances before, but this time things got out of hand and William ended up dead. With their mother's contrivance, the two boys had buried him in a shallow grave, ploughing over the whole field next morning to conceal their work. Jessup had known about the crime too, though whether he played any role in the body's disposal remains unclear.

Charlie was tried for murder at Stuart in December 1914, found guilty and sentenced to ten years. According to the Winston-Salem Journal, he served about seven years before a petition from sympathetic friends and neighbours persuaded Virginia's governor to grant him a pardon. He took a job in West Virginia's coal mines, where an explosion killed him in August 1922 at the age of just 29. The Union Republican reported that he'd been "blown into three pieces" and would be buried at the family cemetery near his mother's home in Patrick County. If he really was Loafing Charlie, then the name seems a most unjust one. (2, 3)

Sources

1) Western Sentinel, 23 January 1914.

2) Winston-Salem Journal, 11 August 1922.

3) Union Republican, 17 August 1922.

[My thanks to Claire Santry of Irish Genealogy Toolkit for her work on both Charlie D. Lawson and Charlie W. Lawson's family trees.]

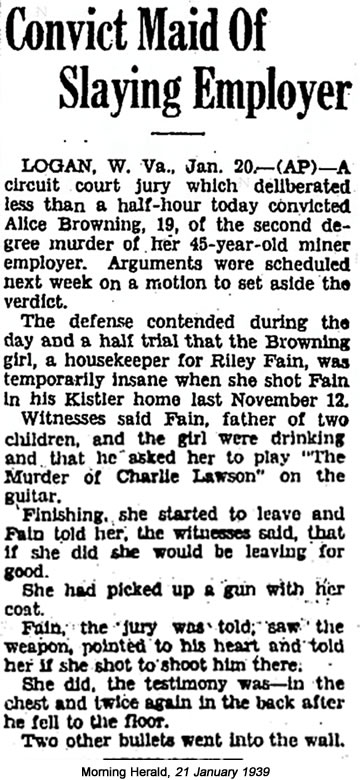

Lawson Family: The Cleaner

This story, which came to light as part of my Lawson Family research, first appeared in a Uniontown, Pennsylvania newspaper. The lesson seems to be that, if you're about to fire your housekeeper, don't plant the idea of murder in her head first.

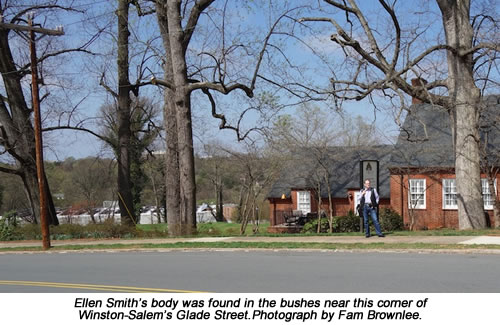

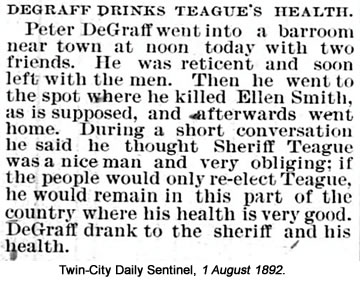

Poor Ellen Smith: Teague party

Peter DeGraff fled from Winston to Mount Airy after killing Ellen Smith, and this allowed him to remain at liberty for a full year. The Twin-City Daily Sentinel, which was determined to remove county sheriff Milton Teague from office, used Teague's failure to capture DeGraff to launch a campaign against him.

This ran the gamut from serious factual charges to highly dubious stories which Teague would nonetheless have found impossible to disprove. The thrust of these was always to make him look both a fool and a coward. DeGraff, on the other hand, was presented as a swashbuckling figure who ran rings round Teague with contemptuous ease.

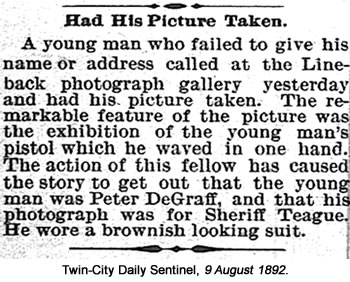

One line the paper took was to claim DeGraff had been sighted in various Winston shops or bars, always behaving in a way that suggested he did not fear Teague in the least. In fact, we know he was already in Mount Airy by the end of July 1892 and would not set foot in Winston again until June 1893. And yet - if you believe the T-CDS - here he is toasting Teague's health and having his photo taken:

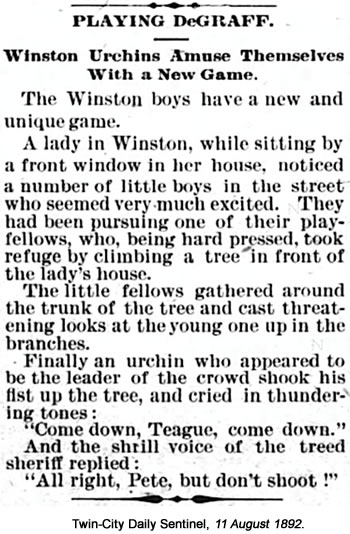

When the novelty of reporting supposed sightings of DeGraff waned, the T-CDS switched to concocting little fables about children's games or the homely wisdom of North Carolina's farmers. These stories always held Teague up as a laughing stock, but were sourced so vaguely he had no chance of fighting back. Here's a couple of my favourite examples:

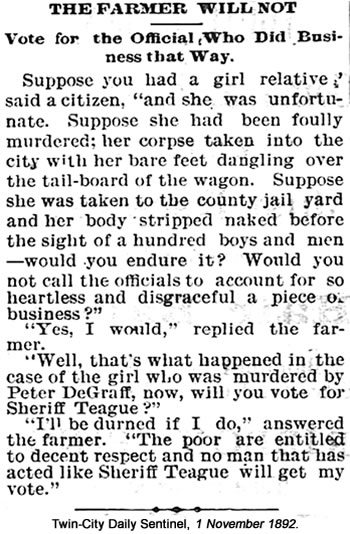

Teague, a Republican, came up for re-election as sheriff on 11 November 1892, when he faced a tough challenge from the T-CDS's preferred candidate, a Democrat named Bob McArthur. As election day drew closer, the paper stepped up its campaign, reminding readers that Teague had done nothing to stop the indignities visited on Ellen at her very public autopsy. Did the farmer above really exist? I doubt it.

Teague lost the election to McArthur, who duly replaced him as Forsyth County's sheriff. Everyone agreed it was Teague's failure to capture DeGraff - combined with the T-CDS's determination to keep this issue in the public eye - which cost the old sheriff his job. DeGraff was arrested when he returned to Winston in June 1893, found guilty of Ellen's murder, and had his hanging day set for 8 February 1894. All the Winston papers reported on his execution with great glee, but only the T-CDS's sister title the Western Sentinel saw it as a chance to chase bad debts:

Tom Dooley: Visiting the dead

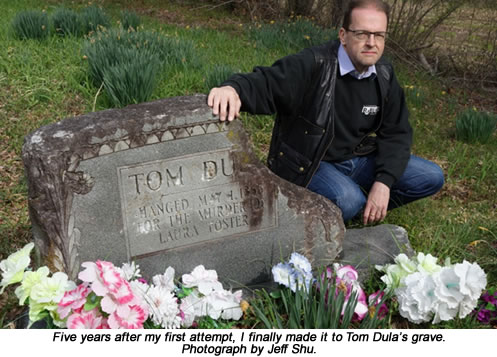

My first attempt to find Tom Dula's grave, back in 2010, was not a success. When I returned to North Carolina in April 2015, I decided to have another go.

This time, I had a much better set of directions to work from, plus the help of a local musician who'd offered to act as my chauffeur and guide. Jeff Shu, the pedal steel guitar player with Winston-Salem's leading honky-tonk twangmeisters The Bo-Stevens, picked me up in the centre of town and off we went. The band's got a handful of murder ballads in its own repertoire - some written by Jeff himself - so I knew we'd have plenty to talk about.

As we headed west towards Wilkesboro, Jeff and I kicked around everything from the coming Presidential election to a recent loosening in NC's own gun laws. I'd been puzzled by a sign in the middle of town saying it was now legal to carry concealed handguns in public parks - an idea which seems utterly bizarre to a visiting Brit - so I was glad to have a Winston-Salem resident there to explain the background for me. US politics and the country's gun laws are subjects I don't get to discuss half as much as I'd like back in London, which means the conversation was a treat for me.

I was under strict instructions from my publisher to get plenty of photographs on this trip, the idea being to demonstrate that I'd not only researched the book's songs from written sources, but also gone that extra mile in visiting their key sites for myself. We stopped for our first shoot at the Tom Dula highway marker on Highway 268, where I had a chance to discover if I looked more of a prat with my sunglasses on or without them. It was a close call.

The sign's information, combined with the Roadside America print-outs I'd brought along, gave Jeff and I all we needed to find the grave. We were looking for an unpaved farm road on the left of the highway, just over a mile past the marker sign where we'd stopped- and there it was. A dirt access road, running parallel to the highway, blocked by a wooden gate and visible for only the first ten yards or so before disappearing into the trees. The road led up a steepish incline, and the whole area round its gate was plastered with signs declaring it private property and saying all trespassing was forbidden.

I left Jeff to park the car while I squeezed past the end of the gate and set off up the incline to see what I'd find. I'll confess to being a little nervous at this point. My chat with Jeff about North Carolina gun enthusiasts was still very much at the front of my mind. I'm sure I was just being needlessly melodramatic, but there was no doubt I was trespassing here, and it did cross my mind that the consequences might be rather more serious than the few minutes of being yelled at by an irate farmer I'd have expected back in Britian. Still, I'd come too far to stop now. What was it Woody Guthrie said about "No Trespassing" signs? "On the other side, it didn't say nothing / That side was made for you and me."

I was following a long strip of overgrown, uneven land, about 20 feet wide and scattered with dead tree trunks. There was a long fence to my left, marking the beginning of the land in agricultural use, and a line of trees to my right blocking any view of the highway running alongside. After a minute or two, I saw Dula's grave ahead, surrounded by colourful artificial flowers. Someone had recently planted a clump of daffodils there too, though these seemed to be struggling.

I knew from my research that about a quarter of Dula's headstone had been stolen over the years, chipped off and carried away as small souvenirs by idiotic vandals. As I drew closer, I could see now that the whole of the its top right corner was missing, exposing the stone's rough interior to a coating of moss and dirt which bled down to obscure part of the inscription with an ugly stain. It was this revolting desecration of the stone that's led to the land's owner being so suspicious of visitors, and who can blame him?

I squatted down to read the stone's wording: "Tom Dula. Hanged May 1, 1866 for the murder of Laura Foster," it read. That date, I knew, was wrong - 1866 being the year of Foster's death rather than that of Dula's hanging two years later. Jeff had caught up with me by now, so we each posed for a few photographs by the stone, then returned to his car and headed west again along 268. We'd seen the killer's grave, and now it was time to pay our respects at his victim's.

Foster's grave lay about 5 miles on, identified by an upright concrete marker, shaped like a lectern, to the highway's right. Spotting this, we pulled over to see what it said:

DIED MAY 28, 1866

MAY SHE REST IN PEACE

On the 28th of May, 1866, Laura Foster, a beautiful but frail girl, was decoyed from her father's house at German Hill in Caldwell County to a place in Wilkes County and was murdered. Tom Dula (Tom Dooley) was later hanged for her murder. She was buried on the bank of the Yadkin River on the farm of John Walter Winkler. Laura's grave is across the road surrounded by the whitewashed locust fence.

Looking up across the road, we could see the tiny plot fenced off with wooden slats as the sign described. It was at the far edge of a large field, backed by tree-covered hills and protected on the roadside edge by a wire fence which previous visitors' online comments warned was electrified. Jeff and I found an old plank by the side of the road and took turns to force the fence's top strand down so we could each straddle it and step across. It's a manoeuvre I hadn't undertaken since my childhood in Devon, and I'd forgotten just how sharply an electrified wire two inches from your testicles can concentrate the mind.

The field was empty except for a few cowpats, so we made our way to Laura's grave without further incident. Presumably, the wooden fence is there to keep livestock away when the field's in full use. The plot's been spread with white stones to keep the weeds down too, and we found a small bunch of maroon flowers left at her headstone's base.

Laura's stone itself is much smaller than Dula's, though mercifully it remains untouched by vandals. The inscription reads: "Laura Foster. Murdered in May of 1865. Tom Dula hanged for crime." Once again, that date's wrong - a year premature in this case - but more interesting is the fact that even Laura's own gravestone refuses to unambiguously state it was Tom who killed her. I mentioned this to Jeff, reminding him the marker had used the same careful wording. "A lot of people still like to think it was Ann Melton who killed Laura." I explained. "Someone's hedging their bets." We stayed long enough for a few more pictures (I'd decided by then the sunglasses were definitely a mistake), then gingerly negotiated the field's wire fence again and returned to Jeff's car.

Our final stop before returning to Winston-Salem was Whippoorwill Academy & Village, where I'd read they had a small Tom Dula museum. The village comprises a collection of old-timey buildings - a jailhouse, a school, a blacksmith shop and so on - recreating the area's pioneer past. Most striking of all is a wonderfully sinister old wooden chapel, topped by a bell-tower and a tall cross, which looks for all the world like it's been summoned here from the pages of a Stephen King novel.

The whole place was closed up when Jeff and I arrived, but the lady who runs it saw us getting out of the car and kindly offered to give us a quick tour anyway. I cranked the English accent up a notch and did my best to be charming. When I explained I was researching a book, she agreed to open up the Tom Dula museum's building and left us to make a fuss of her dog while she went off to find the keys.

Among the exhibits we found inside was a massive diorama depicting Dula's execution, a framed lock of Laura Foster's hair and a fragment of Dula's original tombstone. This original stone was replaced by the one we'd just visited in 1959, when The Kingston Trio's hit version of Dula's ballad created a whole new wave of interest in his crime. The Trio's Bob Shane tells me another section of the original stone is now decorating someone's garden in California.

Far and away my own favourite of these exhibits was the diorama. Each of its 15 figures is about four inches high, with Dula himself shown standing in an open cart drawn up beneath the gallows. He's dressed in shirtsleeves and braces, the noose already round his neck and its rope thrown over the gallows' crossbeam. He's addressing the crowd, his right hand outstretched to make a point, as a dozen grim-face spectators look on. The sheriff's there too, rifle in hand, and a patient black horse stands in the cart's shafts, waiting for the command to move forward and leave his passenger dangling.

Dula shares his perch on the cart with two other figures, who I take to be his sister Eliza and her husband George. Whatever Tom's just said, they clearly don't like it much, because Eliza's just buried her face in a tear-stained handkerchief, and George is halfway to his feet, looking both horrified and amazed as he places an arm on Eliza's back to comfort her.

My guess is that the diorama's creator meant to capture their reaction at the moment Dula admitted he really had killed Laura Foster. That confession actually came in writing rather than during his hour-long address from the gallows, but that small degree of artistic licence can be forgiven. In many other respects - the cart, Eliza's presence next to her brother, the fact that Dula really did speak with a noose round his neck - the diorama sticks closely to verifiable fact. It's a lovely piece of work, and I only wish the glass case protecting it hadn't buggered up the focus on all my photographs.

An hour later, Jeff dropped me back at my hotel in Winston-Salem and we said our goodbyes with the sense of a day went spent. The day I'd wasted trying unsuccessfully to find these sites back in 2010 had rankled with me ever since, so I was glad to have finally tied up the loose ends it created. I felt I'd laid an old ghost to rest - and isn't that exactly what visiting someone's grave is supposed to do?

I've put together a set of eight Spotify playlists to go with my book, each one carefully selecting the most interesting recordings of their chosen song down the decades.

To hear these playlists, just click the Spotify link above and search for "U2D" (which is the prefix I've used for all Unprepared To Die's playlists). If you're not already a Spotify user, you may have to open an account with the site first, but you'll still have the option of streaming all the music free. Don't forget, you're looking for the Playlists section rather than Artists, Albums or Profiles, all of which seem to be stuffed with some earnest-looking Irish fellas.

Each playlist is about an hour long. The full list of songs covered is:

U2D: Stagger Lee

U2D: Frankie & Johnny

U2D: Knoxville Girl

U2D: Hattie Carroll

U2D: Tom Dooley

U2D: Pretty Polly

U2D: Poor Ellen Smith

U2D: Lawson Family