"For the best part of three hundred years the common folk have been unable to shake this melodrama out of their imagination."

"For the best part of three hundred years the common folk have been unable to shake this melodrama out of their imagination."

- AL Lloyd on the song's English origins.

"America's favourite crime story, the same tale that Dreiser used in An American Tragedy."

- Alan Lomax, Bad Man Ballads.

"The first time you hear Pretty Polly, you giggle nervously. The dark forest flowing with blood, the beautiful girl, the open grave – it makes you dizzy with a strange mixture of horror and delight."

- Rennie Sparks, The Handsome Family.

At first glance, Pretty Polly is just one more "murdered girlfriend" song. Like Knoxville Girl, it has its roots in a very old English ballad telling of a young man who knocks up his girlfriend and then stabs her to death rather than marry her. And like Knoxville Girl, the source ballad emigrated to America with European settlers where it was drastically cut from its original epic length to form a lean, mysterious and brutal folk song.

So far, it's all familiar stuff. But there are two elements which set Pretty Polly apart from any other murder ballad I know, and they combine to make its protagonist one of the most chilling the genre has yet produced. "He, unlike so many murder ballad beaus, does not murder 'the girl he loved so well'," says The Handsome Family's Rennie Sparks. "His love for Polly was always rotten with the desire to kill." (1)

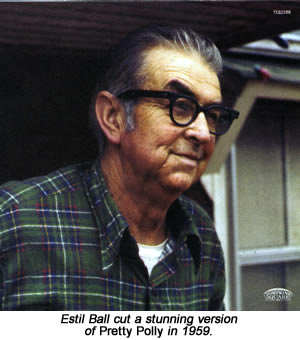

To see why that is, let's start with the moment Polly first glimpses the lonely spot Willie - the young man in question - has chosen for her murder. As he leads her deeper and deeper into the woods, Polly begins to fear this is not the innocent stroll he promised. Estil Ball, in his 1959 recording, describes what follows like this:

They went up a little further, and what did they spy?

They went up a little further, and what did they spy?

A new-dug grave with a spade standing by.

Polly tells Willie she's afraid, and he confirms her worst fears. BF Shelton's 1927 version gives him these words:

"Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, your guess is just right,

Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, your guess is just right,

I dug on your grave six long hours of last night."

It's clear now that Willie was determined to kill Polly long before he even suggested that walk in the woods, and that he's calmly prepared the ground for her slaughter. "This is no crime of passion," Sparks points out. "He stayed up all night to dig her grave ahead of time. You can see him there, measuring the hole, straightening the sides, laying the spade just so. He may be a serial killer. He may be completely insane."

There's more evidence for this is in The Stanley Brothers' 1950 recording, which gives Willie a second, equally psychotic, little speech. Realising that he plans to kill her, Polly falls to her knees, swearing to leave town and raise the child alone. If he'll only spare her life, she says, he need never set eyes either of them again. But Willie is unmoved:

"Oh Polly, Pretty Polly, that never can be,

Polly, Pretty Polly that never can be,

Your past reputation's been trouble to me."

In most other versions of the song, Willie stabs Polly just seconds after they reach her grave, but the Stanley boys give him this sadistic little pause first. "He lingers there with his knife, enjoying her terror," Sparks says. "He says he's heard stories. He has suspicions. He's sure that, hiding somewhere under Polly's pure white veils, there is a dirty slut who deserves to die."

Only a handful of the song's later interpreters have had the stomach to include this particular verse, but Angela Correa was one of them. In her 2004 recording, she manages to make it a notch darker yet by having Willie address Polly as "Honey" when he delivers its final line. The way she sings it makes Willie sound genuinely fond of Polly, but no less resolved to kill her anyway.

I've picked out the most striking examples of the particular verses above, but the ideas they contain are present in just about every version of Pretty Polly. All but the Stanley Brothers' coda can be traced directly back to the 18th century ballad which inspired the song, and so can another characteristic which marks Willie as a very modern killer. It's what the music writer Hank Sapoznik calls Pretty Polly's "bleak, shifting perspective". (2)

Unlike any other murder ballad I can think of, Pretty Polly is constantly switching its narrative point of view, forcing the singer to speak as a neutral witness in one verse, as the killer in another, and as Polly herself in a third. To get the most out of the song, performers must constantly be hopping from one persona to the next, and I think the same may be true of the man it depicts.

Real murderers often speak of stepping outside themselves at the moment they killed. Stuart Harling, for example, who stabbed a Hornchurch nurse to death in 2006, said that he'd felt "as if he were watching himself stab someone in a film or a computer game". Dakotah Eliason, who shot his grandfather dead in Michigan four years later, told detectives he'd "felt at if he were watching a movie about himself " when he pulled the trigger. (3, 4)

The thriller writer Boris Starling describes Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment in similar terms. "It's all about how the murderer disassociates himself from the act of murder," he said in a recent interview. "It's written in the third person, of him watching himself perform the murder. That's what happens." (5)

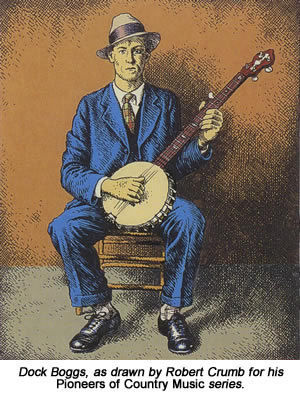

And it happens in Pretty Polly too. In Dock Boggs' 1927 recording for example, the killer describes his early acquaintance with Polly in frank, first-person terms: "I used to be a rambler, I stayed around in town". But the moment he consigns her body to a shallow grave is left for the witness to tell: "He threw the dirt over her and turned away to go". The same switch of viewpoints appears in many other versions of the song, including Bert Jansch's 1963 recording. "I courted Pretty Polly the live-long night," Jansch sings in his first verse. A few lines later, when the actual killing has to be described, this becomes: "He stabbed her to the heart".

One reading of this is to assume the killer and the witness are the same man, but that Willie feels he's watching the murder itself from a vantage point outside his own body - just as Harling and Eliason report doing. Most recordings give Polly just a single verse of narration, leaving Willie to hop between his two different perspectives for the rest of the tale. Always, it is the goriest passages where he chooses to step back and describe events from the outside.

If that seems too fanciful, then consider this discussion of Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer on Adam Pearson's Words From The Wind blog. "Both men have expressed in their interviews that they felt themselves torn between a sense of vivid first-person agency and a sense of disconnected third-person spectatorship," Pearson writes. "It seemed at times as if they became mere spectators to their own actions, watching themselves, as if from outside, carrying out the brutal murders of innocent individuals." (6)

All this suggests that the decades of folk wisdom that went into distilling Pretty Polly managed to intuit some truths about violence it would take scientists another 100 years to codify. For Rennie Sparks, it's still Willie's dark suspicions about women which link him so closely to the monsters of our own day.

All this suggests that the decades of folk wisdom that went into distilling Pretty Polly managed to intuit some truths about violence it would take scientists another 100 years to codify. For Rennie Sparks, it's still Willie's dark suspicions about women which link him so closely to the monsters of our own day.

"Who is this snickering psycho?" she asks. "He's the man in the black raincoat who tried to lure me into his car with a lollipop when I was six years old. He's Ted Bundy with a fake cast on his arm, asking women to help him load a pile of books into the back of a van. He's Ed Gein, who slaughtered and skinned the women who wounded his heart then danced round his yard wearing their bloody faces for a mask. How pretty he must have felt, blood-soaked and screaming in the moonlight."

No doubt he did - and perhaps that's why some versions of Pretty Polly draw our attention as much to the killer's good looks as to Polly's own. Before Willie was any of the people Sparks mentions though, he was a humble ship's carpenter in the English town of Gosport. And that's where we'll meet him next.

Every singer gives their own little twist to Pretty Polly's lyrics, choosing whichever verses they prefer from the 30-odd available and tweaking the words of its key lines to suit their particular interpretation.

I have 37 recordings of the song in my own collection, ranging from the epic 13 verses used by BF Shelton in 1927 to the bare-bones three verses Sarah Elizabeth selected 80 years later. There are a handful of key incidents and images which almost everyone includes, however, and an archetypal version might look like this:

"Oh Polly, Pretty Polly, come go along with me,

Polly, Pretty Polly, come go along with me,

Before we get married, some pleasure to see."

He led her over hills and valleys so deep,

He led her over hills and valleys so deep,

Polly mistrusted, and she began to weep.

"Oh Willie, dear Willie, I'm feared of your ways,

Willie, dear Willie, I'm feared of your ways,

I'm feared that you'll lead my poor body astray."

She went a little further and what did she spy?

She went a little further and what did she spy?

A newly-dug grave with a spade lying by.

"Oh Polly, Pretty Polly, you've guessed about right,

Polly, Pretty Polly, you've guessed about right,

I dug on your grave the best part of last night."

He stabbed her in the breast and her heart's blood did flow,

He stabbed her in the breast and her heart's blood did flow,

And into the grave Pretty Polly did go.

He threw a little dirt over her and turned to go home,

He threw a little dirt over her and turned to go home,

Leaving no-one behind but the wild birds to mourn.

This bleak little tale has its roots in the English town of Gosport in Hampshire. Gosport lies on the south coast of England, just three miles west of Portsmouth, a city that's been the home of Britain's Royal Navy since 1527. Gosport has always existed mostly to serve the Navy's needs, supplying that market with meat, bread, timber, rope, beer, iron tools and labour. "Gosport can claim little that is attractive," one 18th century visitor wrote. "The town has the narrowness and slander of a small country town without its rural simplicity and with a full share of the vice of Portsmouth, polluted by the fortunes of sailors and the extravagances of harlots. To these evils are added the petty pride and sectarian bigotry of a fortified town." (7)

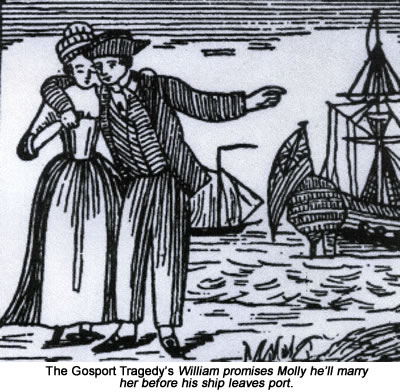

Sailors' tales were a fertile source of material for the printed ballad sheets sold throughout Britain in the 18th and 19th Centuries, and Pretty Polly grew from one of the hardiest examples. Its full title is The Gosport Tragedy or The Perjured Ship-Carpenter.

The oldest copy we have of this song is part of the British Library's Roxburghe Collection, a series of scrapbooks pulling together about 1,500 ballad sheets printed between 1567 and 1790. I'm going to call this copy the Roxburghe Gosport to distinguish it from the many later sheets that followed, and the British Library believes it was printed in the first half of the 18th Century.

The sheet is about A3 size in our terms, printed at a shop in London's Bow Churchyard, and illustrated with a generic woodcut of six people in a row-boat. It takes 34 verses to tell its story - 136 lines in all - separating each stanza from the next with a simple paragraph indent to cram everything in. What happens is this:

A young ship's carpenter called William meets a bright, beautiful Gosport girl named Molly and asks her to marry him. She's reluctant at first, saying she's too young to wed, that she fears William will soon tire of her, and that his job means he'd spend half his time at sea anyway. Bubbling beneath all this is Molly's clear suspicion that William's proposed only because he wants to get into her pants and that, once he's achieved this objective, all his promises of marriage will be forgotten. "Young men are so fickle, I see very plain," she reminds him. "If a maid is not coy, they will her disdain."

William persists for the next four verses, and eventually talks Molly into a night of what the ballad calls "lewd desire". She discovers she's pregnant in the very next line, and reminds William of his promise to marry her. By this time, the king is preparing Portsmouth's fleet to depart on a war mission, but William assures Molly he'll make good on his vow before the Bedford, his own ship, sets sail.

So, with kind embraces, he parted that night,

She went to meet him in the morning light,

He said: "Dear charmer, thou must go with me,

Before we are wedded, a friend to see."

He led her through valleys and groves so deep,

At length, this maiden began for to weep,

Saying: "William, I fancy thou leads't me astray,

On purpose my innocent life to betray."

He said: "That is true, and none can you save,

For I all this night have been digging a grave",

Poor innocent soul, when she heard him say so,

Her eyes like a fountain began for to flow.

"Oh perjur'd creature, the worst of all men,

Heavens reward thee when I'm dead and gone,

Oh pity the infant and spare my life,

Let me go distress'd if I'm not thy wife."

Her hands white as lilies, in sorrow she wrung,

Beseeching for mercy, saying: "What have I done,

To you, my dear William? What makes you severe?

For to murder one that loves you so dear?"

He said: "There's no time disputing to stand",

And, instantly taking the knife in his hand,

He pierced her body till the blood it did flow,

Then into the grave her body did throw.

He covered her body, then home he did run,

Leaving none but birds her death to mourn,

On board the Bedford, he enter'd straightway,

Which lay at Portsmouth out-bound for the sea.

There's another 56 lines of the Roxburghe Gosport to go at this point, but we'll come back to them in a moment. What's clear from the seven verses above is that just about every key element of Pretty Polly was already there in The Gosport Tragedy almost 300 years ago.

There's another 56 lines of the Roxburghe Gosport to go at this point, but we'll come back to them in a moment. What's clear from the seven verses above is that just about every key element of Pretty Polly was already there in The Gosport Tragedy almost 300 years ago.

The Roxburghe Gosport alone gives us the walk to a secluded spot, the passage through hills and valleys, the girl's growing suspicions leading to tears, the grave her killer has already prepared, the knife as his chosen weapon, her blood spilt on the ground and his casual disposal of the body. The English ballad has the same mix of narrators who later appear in Pretty Polly too. Willie's given the slightly more formal name of William, and his victim is Molly rather than Polly, but these are the tiniest of changes.

All that's missing is the striking moment when Polly first sights her "newly-dug grave with a spade lying by". That enduring image appears nowhere in the Roxburghe Gosport itself, but researchers have traced it back to other English ballad sheets printing the same song just a few years later. Some date the grave-and-spade stanza to between 1750 and 1800, but the earliest example I've been able to find comes from an eight-page chapbook printed by the Paisley bookseller George Caldwell in 1808. He makes The Gosport Tragedy his lead song in the book's selection and includes this couplet:

A grave and spade standing by she did see,

And said: "Must this be a bride-bed for me?"

Many early sheets suggest The Gosport Tragedy's lyrics be sung to an old English tune called Peggy's Gone Over Sea, but the fact that its lyrics follow a ballad's structural rules means many other tunes fit just as well. Pretty Polly follows ballad rules too, of course, so all we need do to make the original British words fit the American tune we know today is add a few repetitions and tidy up the scansion a little. The first couple of verses, for example, could easily be rendered like this:

He said: "My dear charmer, thou must go with me,

He said: "My dear charmer, thou must go with me,

Before we are wedded, a friend for to see."

He led her through valleys and groves so deep,

He led her through valleys and groves so deep,

At length, this poor maiden began for to weep,

I doubt if any single version of Pretty Polly includes every one of the ideas in the first Gosport Tragedy extract I gave here, but all survive somewhere in the American song's tangled branches.

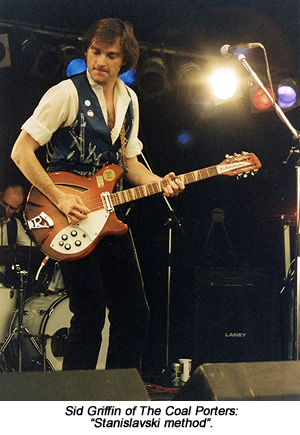

"Heavens reward thee when I'm dead and gone" - here used to mean "punish" rather than "reward" in the modern sense - is echoed on Pretty Polly discs stretching all the way from BF Shelton in 1927 to The Coal Porters in 2010. Peggy Seeger's 1964 version has Willie declare that "killing Pretty Polly will send my soul to hell", and Queenadreena's 2000 recording makes the same point when it reminds us there's "a debt to the devil Willie must pay".

Molly's appeal to William that he should "let me go distress'd if I'm not thy wife" has its equivalent in Pretty Polly too. The Stanley Brothers' were the first artists to have Polly beg "let me be a single girl if I can't be your wife", but that plea's been echoed by Judy Collins in 1968, Patty Loveless in 1997 and many others besides.

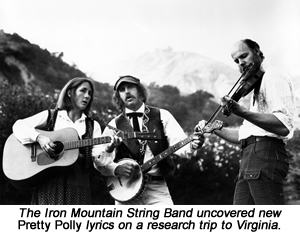

Molly's "lily-white hands" have never quite gone away either, attaching themselves to Polly's arms in versions by Dock Boggs (1927), The Iron Mountain String Band (1975) and Angela Correa (2004). Molly's astonishment that William could "murder one that loves you so dear" is given to Polly on discs by John Hammond in 1927, Pete Seeger in 1957 and Sweeney's Men in 1969.

The killer's determination to hurry things along - "There's no time disputing to stand" - is dotted through Pretty Polly's whole recording history too. It's book-ended in my own collection by Hammond's "There's no time for talking, there's no time to stand" in 1927 and Beate Sampson's almost identical wording 82 years later. As in The Gosport Tragedy's original couplet, this line is almost invariably followed by one which both mentions the knife and uses "hand" as a convenient closing rhyme. Uncle Sinner's verse from his 2008 recording is just one of many examples:

There's no time for talkin', there's no time to stand,

There's no time for talkin', there's no time to stand,

I drew up a hunting knife in my right hand.

Looking at all the evidence above, only one conclusion is possible: Pretty Polly comes from The Gosport Tragedy. All we have to do now is figure out where The Gosport Tragedy came from and the answer to that question lies in a Florida folklore journal published 30 years ago. (8)

As soon as Molly's dead and buried, the Roxburghe Gosport turns its attention to William's life on board the Bedford. He's lying in his bunk one night, when he hears Molly's ghost calling him:

"Oh, perjur'd villain, awake now and hear,

The voice of your love, that lov'd you so dear,

This ship out of Portsmouth never shall go,

Till I am revenged for this overthrow."

She afterwards vanished, with shrieks and cries,

Flashes of lightning did dart from her eyes,

Which put the ship's crew into great fear,

None saw the ghost, but the voice they did hear.

Molly's spirit seems to hope that William will confess to the murder and turn himself in. When he refuses to do so, the ghost decides to appear directly to the crew as well:

Charles Stuart, a man of courage so bold,

One night was going into the Hold,

A beautiful creature to him did appear,

And she in her arms had a daughter most fair.

The charms of this so glorious a face,

Being merry in drink, he goes to embrace,

But to his surprise, it vanished away,

So he went to the captain without more delay.

And told him the story which, when he did hear,

The captain said "Some of my men, I do fear,

Have done some murder, and if it be so,

Our ship in great danger to the sea must go."

This refers to the belief, common among seamen at the time, that sailing with a murderer on board your ship put the whole vessel in great danger. We have evidence of this from several other 18th Century ballads, including William Glen, which is set aboard a ship beset by inexplicable storms. Discovering their captain committed murder before leaving port, the crew throws him overboard, at which point the storms instantly subside and they sail safely on. "All young sailors, I pray beware," the ballad concludes. "And never set sail with a murderer".

This refers to the belief, common among seamen at the time, that sailing with a murderer on board your ship put the whole vessel in great danger. We have evidence of this from several other 18th Century ballads, including William Glen, which is set aboard a ship beset by inexplicable storms. Discovering their captain committed murder before leaving port, the crew throws him overboard, at which point the storms instantly subside and they sail safely on. "All young sailors, I pray beware," the ballad concludes. "And never set sail with a murderer".

The Gosport Tragedy's own supernatural scenes may have been inspired by an 18th century ballad called The Dreadful Ghost. This tells the story of girl who hangs herself after being impregnated and abandoned by her boyfriend. He flees to sea in hopes of escaping the girl's vengeful spirit, but she follows him on board and tells the captain to hand him over:

"And if you don't bring him up to me,

A mighty storm you soon shall see,

Which will cause your gallant men to weep,

And leave you slumbering in the deep".

The terrified crew drags her former boyfriend on deck, and the ghost forces him into a row-boat which promptly bursts into flames and sinks with him in it. The ghost then ascends to heaven, giving this final warning: "You sailors all who are left behind / Never prove false to young womankind". Many versions of The Gosport Tragedy close with a light re-phrasing of exactly that moral. (9)

Returning to our own ballad, the Bedford's captain knows their departure date is drawing near, so he calls all the men into his cabin one by one and confronts them with his suspicions. Soon, it's William's turn:

Then William, afrighted, did tremble with fear,

And began by the powers above to swear,

He nothing at all of the matter did know,

But as from the captain he went to go,

Unto his surprise, his true love did see,

With that, he immediately fell on his knee,

And said "Here's my true love, where shall I run?

O save me, or else I am surely undone."

Now he the murder confessed out of hand,

And said "Before me, my Molly doth stand,

Sweet injur'd ghost, thy pardon I crave,

And soon I will seek thee in the silent grave".

No-one but this wretch did see this sad sight,

Then, raving distract'd, he died in the night,

As soon as her parents these tidings did hear,

They fought for the body of their daughter dear.

Near a place called Southampton, in a valley so deep,

The body was found, while many did weep,

At the fall of the damsel and her daughter dear,

In Gosport churchyard, they buried her there.

Southampton's just 14 miles north-west of Gosport, and only 17 miles from Portsmouth, so all the locations given in the Roxburghe Gosport are consistent with one another. It offers a couple of other important clues too, telling us that the ship involved was the Bedford and that it was moored in Portsmouth harbour when the murder took place. William and Molly are both generic names, used in countless ballads of the time no matter what the real individuals were called, so there's not much to be learned there. Charles Stuart looks a bit more reliable, though, and the ballad is clear the Bedford's crew included someone of that name when the ghost appeared.

Armed with this information, the University of Washington's Professor David Fowler set about researching Royal Navy records to see how many of the Roxburghe Gosport's details he could confirm. The resulting essay, which appeared in a 1979 volume of Florida University's Southern Folklore Quarterly, provides our best account of the ballad's background yet. (10)

Fowler's first problem was to decide which decade - or even which century - to begin his search. The British Library gives two different dates as its best estimate for the Roxburghe Gosport's printing, opting for 1720 in its General Catalogue (GK), but for 1750 in its English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC). Both carry a cautionary question mark to indicate they're only approximations. (11)

Fowler took the first of the British Library's two dates as his starting point and quickly discovered that there really was an HMS Bedford at this time. She was the first of three Royal Navy warships to bear that name, and launched from Woolwich Dockyards in September 1698. This Bedford was what Fowler calls "roughly the equivalent of a destroyer in the modern navy", measuring 150 feet long by 40 feet wide, with 70 guns on board and a full complement of 440 men. (12)

The ship survived in that form until 1736, when orders came to demolish and rebuild her in accordance with new Navy standards. This process was not completed until 1741, when she was relaunched from Portsmouth in her new form. The Bedford was reduced to a hulk in November 1767, and sold off 20 years later. Fowler discovered from Navy records that, except for short stays in Chatham and Woolwich, she was based at Portsmouth from 1710 until 1740.

Let's assume for the moment that The Gosport Tragedy really was inspired by a real crime. HMS Bedford wasn't built until 1698, so that's the earliest that any real-life murder matching the ballad's description could have occurred. The British Library's dates suggest around 1750 as the latest possible date for any such crime, and that rules out all but the first warship to bear the Bedford's name. So far, so good: we've got the right ship in the right port at the right time.

Fowler's next step was to dig out the Bedford's pay books, muster books and captain's log from the crucial period - all of which can still be found at the UK's National Records Office in Kew. Starting in 1699, he read down the long lists of every crewman's name, looking for a Charles Stuart, or some alternative spelling of the same name. He hit paydirt with the entry for January 27, 1726, when the muster book notes that one "Charles Stewart" has joined the crew. Stewart remained on board the Bedford for at least two years, and he's the only man of anything like that name Fowler was able to find on-board.

"The existence of the Bedford, and the confirmation that she was indeed in Portsmouth, as the ballad says, provides justification for taking seriously the name of Charles Stewart, the third piece of evidence from the ballad thus confirmed by Admiralty documents," Fowler says in his essay.

The ship's carpenter when Stewart signed up is listed as John Billson, who joined the Bedford in that post on May 1, 1723, and remained there till his death on-board in September 1726. That means Stewart and Billson were shipmates there for eight months. "Billson's first name is not William, but William and Molly are common names in balladry," Fowler reminds us. "Enough so to at least justify pursuing Billson a bit further."

For the two-and-a-half years before Stewart signed up, the Bedford had been serving as a guard ship in Portsmouth harbour, with a skeleton crew of about 80 men on-board. Quiet periods like this were a golden opportunity for Billson and his gang of eight to twelve junior carpenters to carry out any repairs the ship needed. "The work of the crew, and particularly the carpenters, was primarily a matter of maintenance, which in a wooden sailing vessel of this date was a constant problem," Fowler says. "The ship's crew worked during the day, but had shore leave on a fairly regular basis."

To illustrate this point, Fowler quotes a Madden Collection ballad called New Sea Song which, he says, "gives the sailor's view of such duty":

To illustrate this point, Fowler quotes a Madden Collection ballad called New Sea Song which, he says, "gives the sailor's view of such duty":

Our ship, she is unrigged, all ready for docking,

Straightway on board of these hulks we repair,

Where we work hard all day, and at night go a-kissing,

Jack Tar is safe moored in the arms of his dear.

Billson left no widow behind to receive his out-standing Navy pay after death, so we know he was a single man. If he really is the model for William, this spell of guard ship duty would have been his ideal opportunity to seduce Molly with the promises of marriage the ballad records and enjoy her to the full when those efforts prevailed. Ample time too, for Molly to discover her delicate condition, and remind William of his obligations to her more forcefully each day. She knew full well that a Navy carpenter had to sail with his ship when hostilities broke out - "in time of war, to the sea you must go" - and that peaceful interludes like these never lasted for long.

And so it proved. On January 26, 1726, Edmund Hook, the Bedford's captain, received orders that he should prepare the ship for active duty. Spain had joined with Austria to threaten the British territory of Gibraltar, and was now thought to be plotting with Russia too. Acting on Admiralty advice, King George I ordered the Bedford and 19 other Royal Navy ships to stage a show of force in the Baltic and remind the Russian navy that Britain wasn't to be messed with.

Hook's log entry for January 26 reads: "This forenoon, received their Lordships' direction to man and get fit for channel service as soon as possible, to the highest complement, together with four press warrants which I issued out to my lieutenant to be put into execution". (13)

The new orders meant Hook had to get the Bedford's crew up from the minimal 80 men it used as a guard ship to its full complement of 440, and to get this done in double-quick time. The press-gang warrants gave his men the legal powers to force any seamen they found in Portsmouth's pubs and brothels to join the Bedford whether they liked it or not - a crude form of conscription. In extreme cases, reluctant recruits were simply knocked unconscious and dragged on board against their will. This practice was known at the time as "pressing" or "impressing" the crew.

The new orders sharply increased the workload for Billson and his gang of carpenters too, as Hook began pushing them to complete the thousand and one jobs needed to get the ship ready for active service.

"The crisis in the lovers' relationship comes on 26 January 1726 with the news that the Bedford is to be outfitted for duty with the Baltic fleet," Fowler suggests. "Word goes out that 'the king wants sailors' (as the ballad reports), and impressing of the ship's crew begins. Possibly at this time, the girl informs the carpenter that she is with child, in the hope that this will persuade him to marry her before going to sea."

If Billson really did have a pregnant girlfriend ashore, she'd have known his departure was now looming very near, and that there was no guarantee he'd ever return to Gosport again. If she was going to get him to marry her - no small matter for a single girl in her condition at the time - then she couldn't afford to let him forget the issue for a moment. Billson's only escape from this would have been the equally relentless pressure he faced at work, so his mood would have been far from sunny.

On January 27, 1726, the day Stewart signed up, Hook's log confirms the Bedford has already begun press-ganging new men and getting them on-board. Stewart's own name in the pay book has the single word "pressing" noted against it, but he does not appear on a separate list of men recruited in this way. Fowler concludes that "pressing" was an indication of Stewart's duties rather than the reason he joined.

Although he gave his signature on January 27, Stewart did not come aboard the Bedford until two weeks later, and Fowler thinks that's because he was busy ashore recruiting others. "As a press gang member, he would have been more likely than the average to be known personally to the captain, and would spend more time ashore when the ship was in port," Fowler says. This may help to explain why the Stewart of the ballad was so willing to take his fears to the captain, and – as we'll see in a moment - why he's the only crewman given his real name in full.

On January 30, the Bedford was towed alongside a hulk in Portsmouth dockyard so Billson and his gang could remove the old mizzen mast and get a new one set in its place. Next day, they began the huge job of lightening the ship by removing anything that wasn't nailed down so she could be hauled into dry dock for her caulking to be renewed. The ship spent from February 5 to February 7 in dry dock, with Billson and his gang working on her all this time, and then returned to Portsmouth harbour, where she spent the next three weeks.

All this time, Hook's frantic efforts to rope in the crew he needed were continuing. He'd got the total up to 410 men by the time the Bedford sailed out of harbour to the Navy's Portsmouth anchorage at Spithead on February 26, at which point shore leave became very rare. Still, Hook was adding new men every day, eventually getting the ship up to a strength of 486 crew against its supposed capacity of 440. The Bedford stayed at Spithead for six weeks as she and the rest of Admiral Sir Charles Wager's fleet completed their preparations, then sailed for the Baltic with everyone else.

All this suggests that any real murder behind The Gosport Tragedy - and therefore behind Pretty Polly as well - most likely happened between January 26, 1726 and February 26 the same year. Any earlier, and the Bedford would still have been months away from sailing. Any later, and its carpenter would have had no opportunity to murder Molly or anyone else in Gosport. Once the Bedford left for Spithead, John Billson would never tread on English soil again.

Fowler's own guess is that Molly announced her pregnancy towards the end of January, just as the Bedford was getting ready to go into dry dock, and that the murder itself came around February 1. "Her news drives the carpenter to desperate measures," Fowler writes. "He kills his mistress, buries her in a lonely place, and returns to his ship, where he is now caught up in a whirlwind of activity preparing the Bedford for sea duty."

The six weeks at Spithead that followed trapped the entire crew on their over-crowded ship, but gave them far less work to do than the frantic preparations in harbour. Fowler thinks this is when gossip about a ghost on-board may have started circulating. Perhaps this began because someone in the crew noticed Billson was having disturbed nights, or perhaps because he was foolish enough to confide in one of the other men.

"The first stirrings of conscience start to haunt the carpenter, and the first rumour of voices heard in the night begin to come from the crew," Fowler writes. "The ballad offers some support for the anchorage setting in the cry of the ghost: 'This ship out of Portsmouth never shall go / Till I am revenged for this overthrow', meaning that the Bedford shall not leave the Portsmouth anchorage [at Spithead] until she has her revenge."

With little to do in their off-time but get drunk, rumours of a ghost swirling throughout the ship and plenty of time to swap tall stories, the Bedford's crew must have been ready to glimpse spirits in every shadow. It's at this point that a sloshed Charles Stewart stumbles into the dimly-lit hold and sees what he thinks is a beautiful woman holding a baby in her arms. He steps forward to embrace her, but the image instantly vanishes. You or I would conclude this was trick of the light, remind ourselves how primed we'd been to expect something like this, and swear to lay off the rum in future. For an 18th century sailor, though, a very different explanation suggested itself - he'd just seen Molly's ghost! (14)

There's more evidence for Spithead being the setting for this episode in the ballad's report of Hook's reaction. If there really is a murderer on board, the ballad's captain says, then "our ship in great danger to the sea must go". Partly, that line is just a reflection of the seamen's usual superstition about murderers, but the timing it implies is interesting too.

"It does sound as if the captain wished to settle the matter as soon as possible, while at the same time conceding that the ship will probably have to sail before a verdict can be reached," Fowler says. "On these somewhat tenuous grounds, I conclude that the affair of the ghost was reported to the captain by Charles Stewart at about the time of the fleet's scheduled departure from Spithead (April 7), and that the eventual breakdown and confession of the carpenter came at some future time."

"It does sound as if the captain wished to settle the matter as soon as possible, while at the same time conceding that the ship will probably have to sail before a verdict can be reached," Fowler says. "On these somewhat tenuous grounds, I conclude that the affair of the ghost was reported to the captain by Charles Stewart at about the time of the fleet's scheduled departure from Spithead (April 7), and that the eventual breakdown and confession of the carpenter came at some future time."

The Bedford reached the Gulf of Finland at the end of June and anchored at Naissaar Island off the coast of Estonia. The fleet's job there was simply to park somewhere in the Russians' field of vision and stay put for a bit, radiating a quiet sense of British naval power by its presence alone. The more gung-ho Russian commanders were keen to engage the British fleet, but Vice-Admiral Thomas Gordon - who'd defected to Russia's navy in 1714 - persuaded them this would be suicide. After three months in the Baltic, the Admiralty felt Britain's point had been made so the fleet set off back to Portsmouth.

No actual fighting had proved necessary during this expedition, but the voyage home presented some genuine danger. On September 22, the Bedford had reached a point about 150 miles west south-west of Nargen Island - placing her smack in the middle of the Baltic Sea - when storms struck the ship. These storms tore up the Baltic for three days and, as The Weekly Journal later reported, sank no fewer than 17 ships there. It was, The Newcastle Courant adds, "a long and stormy passage".(15, 16)

"At half past 10pm, HF topsail," Hook's log entry for September 22 begins. "At 6am, set fore topsail; broke one of our main shrouds HM topsail. At 8 fixed him again and set main topsail. At 10 saw some breakers bearing NNE 6 or 7 miles; fired a gun being a sign of danger, and tacked."

I asked Admiralty Librarian Jennifer Wraight to translate this log entry into landlubbers' English for me, and she explained that the first section means Hook was hauling in sails on his fore mast and main mast respectively. "Making adjustments to the sails is normally a reaction to weather conditions," she went on. 'In stormy conditions, you would normally reduce the amount of sail a ship is carrying, which would be consistent with the entry you have.

"The shrouds are not sails, but part of the rigging: they provide lateral support for the masts. One of the main shrouds breaking would suggest that the mast was under strain. Taking in the main topsail would have reduced strain on the mast while the broken shroud was being repaired."

There was a second threat too, because the breakers Hook sighted told him there was shallow water and rocks near the ship. Wraight believes these rocks carried more potential danger for the Bedford than the weather alone, adding that they would have been all the more difficult to avoid when storms were cutting both visibility and the ship's capacity to manoeuvre. "Tacking - changing direction - would be eminently sensible," she said. "He's taking the ship away from hazard."

Fowler gives Hook credit for his calm, unemotional language in the log entry, but adds: "There can be no doubt that, on 22 September, the captain of the Bedford considered his ship to be in grave danger. Three days later, John Billson, carpenter, died."

Fowler's theory here is that Billson, still tormented by the fear of supernatural revenge, had by now fallen prey to some unknown illness too. "If, as the ballad suggests, there was a concern on the part of the captain and crew over the possible presence of a murderer on board, the foul weather and the sighting of breakers perilously nigh may well have prompted some of them to begin looking for their Jonah," he says.

Perhaps some of the Bedford's men even threatened to throw Billson overboard, just as those described in William Glen had done to their own jinx. Faced with intolerable stress from both his own guilty conscience and the ill-will of everyone around him, it would be small wonder if the carpenter once again began to fancy he could see Molly's ghost. In a man already weakened by illness, the fits these visions produced could well have proved the final straw. "The death of John Billson provides us with a fourth fact related in The Gosport Tragedy," Fowler says. "Namely, that the carpenter of the Bedford died on board ship."

Fowler calls his whole scenario for The Gosport Tragedy's tale a "hypothetical reconstruction", and I think he'd accept that Billson's death is the point where it becomes most speculative of all. The only thing we know for certain is that Billson died at 9:00am on September 25, 1726. Hook's log entry for that day is his usual long list of times and headings, punctuated by just six words on Billson's death. "At 3am wove to the southward," he writes, "at 6 wove again and stood westward, at 9 John Billson carpenter died, at ½ past tacked westward." (17)

Hook's log entry also tells us that September 25 began with mild winds and fair weather, continuing with clear skies later in the day. That was the first calm morning the Bedford had seen after three days of terrible storms and, if the crew really had blamed Billson for causing these, it must have seemed equally obvious that his imminent death was ending them.

Fowler argues that the ballad's need to concertina all these events together conceals just how much patience Molly's spectre had been prepared to show. "She gets her revenge by alerting the ship's crew and the captain, but is not made a liar by the tardy demise of her victim," he writes.

Hook's terse account of Billson's demise in the ship's log looks callous to modern eyes, but he'd have been well-accustomed to his men dying of various illnesses on board. Fowler has collected figures showing the Bedford lost about 40 of its 486 men to illness during its seven-month Baltic mission. Seven died on the return voyage to Portsmouth alone - including Billson himself - and another five in Gosport Hospital as soon as they reached shore.

We have no official cause of death for Billson, but Fowler thinks it was probably scurvy that did for him. This disease killed more British sailors than enemy action did in the 18th century, and it was not until 1747 that James Lind proved it could be prevented simply by adding citrus fruits to the sailors' very restricted diet. This practice was not adopted by the British Navy until the 1790s, and not fully understood even then.

In his 2005 essay Scurvy: The Sailors' Nightmare, Grant Sebastian Nell describes its final stage as: "a terrible fever which left men raving and ranting before they died". Once again, this does seem to match the ballad's description: "Raving distracted he died in the night". (18, 19)

When I put the scurvy theory to Wraight, however, she was distinctly sceptical. "There are many reasons why Billson may have died, but no apparent reason to assume scurvy," she told me. "It would not normally have been too difficult to obtain supplies of fresh food while serving in the Baltic." In this particular case - as Wraight also pointed out - the Bedford was on a relatively cushy mission, and within easy reach of land throughout the summer. We know Hook's men visited Nargen Island regularly enough, because he set up a tent hospital there to handle the Bedford's sick.

We can't rule out the possibility that Billson died as a result of some random accident on board the storm-tossed Bedford, or even that he had his throat slit by superstitious crewmates. There's no record of any official investigation following his death, however, so some form of illness remains the most likely explanation. Whether it was scurvy or not is a different matter.

The Bedford was over 900 miles from Portsmouth when its carpenter died, about 15 miles from the nearest land, and with over a month of her voyage home remaining. Wondering if there was any point in trying to track down Billson's burial records, I asked Wraight how the ship would have handled his body in a case like this.

"Someone who died on board would have been given a perfectly conventional burial in the nearest available cemetery if this was feasible," she replied. "If the ship was out at sea and this was not practicable, then the corpse would normally have been sewn up in a weighted hammock and buried at sea with due ceremony. [...] Billson would definitely be more likely to be buried at sea than brought home. Sharing a ship with a decomposing body is not pleasant, nor conducive to health and morale. Cases like Nelson's where they did attempt it, are very rare and they didn't find it easy then."

Most likely, John Billson's body ended up at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. His victim on the other hand, as the ballad tells it, was eventually buried in Gosport churchyard. Molly's parents must have been relieved to lay their lost daughter to rest in sacred ground at last, and Fowler thinks it's Charles Stewart who made that possible.

Most likely, John Billson's body ended up at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. His victim on the other hand, as the ballad tells it, was eventually buried in Gosport churchyard. Molly's parents must have been relieved to lay their lost daughter to rest in sacred ground at last, and Fowler thinks it's Charles Stewart who made that possible.

As soon as the Bedford's carpenter has breathed his last, The Gosport Tragedy leaps forward in time again to deal with Molly's burial. The two verses involved, you'll recall, go like this:

No-one but this wretch did see this sad sight,

Then, raving distract'd, he died in the night,

As soon as her parents these tidings did hear,

They fought for the body of their daughter dear.

Near a place called Southampton, in a valley so deep,

The body was found, while many did weep,

At the fall of the damsel and her daughter dear,

In Gosport churchyard, they buried her there.

In fact, it looks as if just over a month must have passed between the second and third lines of this extract. Fowler assumes that Billson confessed all about his crime in the day or two before he died on September 25, but no-one on the Bedford would have had the chance to reach the girl's parents until the ship docked again in Portsmouth harbour on November 4. The ballad's wording therefore implies that her body remained undiscovered in its shallow grave for at least nine months. As the Bedford returned to English waters, all the girl's family could have known was that "Molly" had gone missing around February 1, and that no-one had heard from her since.

Returning to the Bedford's pay and muster books, Fowler discovered a series of new marks against Stewart's name running from November 18, 1726, until April 12 the following year. These, he says, are "a series of check marks indicating a legitimate absence from the ship - that is, he is not being paid on board during this period, but neither is he a runaway". We can rule out Stewart's press-gang duties as a reason for this because the Bedford was set to remain in Portsmouth for the next five months, and would not leave Britain again until May 1727.

Instead, Fowler suggests, Hook picked Stewart as someone he could trust with a different task: find the girl's parents, tell them what happened to their daughter and pass on whatever information Billson had volunteered to help locate her body. "I assume that the captain decided no legal action needed to be taken since, before the ship returned to port, the confessed murderer was himself dead," Fowler writes. "Nevertheless, I think it would be in character for Hook to take responsibility for seeing to it that the carpenter's confession was communicated to the murdered girl's parents."

The Bedford remained in Portsmouth harbour until February 28, 1727, and then sailed back to the anchorage at Spithead, where she spent the next week. On April 9, she left Spithead for a new mooring at the Nore, where the mouth of the Thames meets the North Sea. Stewart rejoined the ship there on April 12, and a week later the marks against his name change again to indicate "paid on board". They remain that way for the rest of the year. That gives him a spell of five months on-shore, during which he seems to have both contacted the girl's parents and told his story to the London print-shop owner who produced the Roxburghe Gosport.

Neither The Gosport Tragedy nor the Navy's records give us any clue to Molly's real identity - even that Christian name is a fiction, remember - which scuppers any possibility of finding her grave. We do know that Gosport's parish church back in 1726 was St Mary's at Alverstoke, though, so that's almost certainly the place the ballad has in mind when it mentions "Gosport churchyard". If Stewart really did manage to trace the girl's parents and give them enough information to find her remains where the killer had dumped them, that would have allowed them to rebury her at St Mary's, just as the Roxburghe Gosport says.

Reverend Ted Goodyer looks after St Mary's today. "We do indeed have a number of gravestones dating back to the early part of the 18th century," he told me. "Holy Trinity Church in Gosport was built in 1695, and did have a churchyard which has now been flattened, so the records of that church may also be helpful." (20)

Fowler searched the burial records, gravestone inscriptions and church wardens' accounts at both St Mary's and Holy Trinity, as well as the era's inquest files, but found nothing of any use. It occurred to me that he may not have thought to look for a "truculenter occisa" (violent death) note like the one that tipped me off in my own Knoxville Girl investigation, but I've now been through St Mary's 1726 and 1727 burial records for myself, and no such note exists.

Surviving newspapers from the 1720s are few and far between, but both Fowler and I have searched those available and turned up nothing that's relevant. If there ever was a real murder behind The Gosport Tragedy, then the ballad itself seems to be our only record of it. But even if the tale's based in nothing more substantive than the Bedford's prevailing gossip, there's good reason to think Stewart had a role in transmitting it to the wider world.

Stewart's progress from Gosport to the Nore during his time away from the Bedford would logically have taken him through London, and perhaps to one of the many seamen's inns there he'd have known there from his work with the Navy's press-gangs. These joints were known as "rondys" - short for "rendezvous" - and there were a couple of big ones near the Bow Churchyard print shop where the Roxburghe Gosport was produced.

"The oldest rendezvous was at St Katherine's Stairs on Tower Hill, the neighbourhood being frequented by seamen because of the proximity of the Navy Office where pay tickets were cashed," Christopher Lloyd writes in his book The British Seaman 1200 – 1860. "A convenient tavern there was The Two Dutch Skippers. Other well-known places in London were the White Swan in King Street, Westminster, and the Cock & Runner in Bow Street." Inns like these kept a "press room" on the premises - essentially a jail cell where men the press gangs had already rounded-up could be safely locked away before being taken to the ship.

We know from Henry Plomer's dictionary of 18th century printers that the Bow Churchyard shop was operated by a man called John Cluer from 1726 till 1728, which puts him in charge there when Stewart passed through London. Fowler suggests that Cluer may have frequented pubs like the Cock & Runner hoping to gather material for future ballads, and that Charles Stewart found him there one night on just such an expedition.

That would certainly explain why Stewart is the only man given his real name in the song, why that name is spelt out in full, and why he's described in such flattering terms ("a man of courage so bold"). Cluer would have been keen to keep such a useful source of material happy, either because he needed more than one interview to get the Gosport story down in full or because he hoped other lucrative yarns might follow. (21)

Just how much of that is true, we'll never know. Someone must have provided the bridge that transformed The Gosport Tragedy from a sailors' oral tale to a printed ballad, though, and the details above make Stewart a very tempting candidate. "He is my choice as the mariner who held a London publisher with his glittering eye," Fowler says, "telling an intriguing story of love, death and the supernatural, which was then turned into one of the most popular broadside ballads of the last 250 years". (22)

Ballad shops all over the UK continued to produce sheets with The Gosport Tragedy's tale right through the 19th century, often adding small improvements to the scansion or cutting its length as they went.

Ballad shops all over the UK continued to produce sheets with The Gosport Tragedy's tale right through the 19th century, often adding small improvements to the scansion or cutting its length as they went.

In some cases, these refinements may have begun in the song's oral tradition, as singers passed it from mouth to mouth and it slowly evolved in response. When that happened, the balladeers had only to transcribe what they'd already heard sung in the streets, but in other cases they'd be composing their own verses from scratch. Whatever its source, the most significant change came when someone decided William was getting off rather too easily in the original song. What was needed here, they felt, was for someone to give him a far nastier death.

It's possible that this change appeared as early as 1805, but the earliest concrete example I've been able to find is a Liverpool sheet produced around 1822. This retitles the ballad Love and Murder, cuts it to just 44 lines, and sets its action in the English town of Worcester. The story is just as we know it, but the girl's name has now morphed from Molly to Polly. Her killer is called Billy, and his entire life after escaping to the ship is condensed into the ballad's final three verses:

One morning before ever it was day,

The captain came up, and this he did say:

"There is a murder on board that has lately been done,

Our ship is in mourning, we cannot sail on".

Then up stepped one: "Indeed it's not me",

Then up steps another: "Indeed it's not me",

At length up steps Billy, and this he did swear:

"Indeed it's not me, I vow and declare".

As he was running from the captain with speed,

He met with his Polly which made his heart bleed,

She stripped him and tore him, she tore him in three,

Because that he murdered her baby and she.

"This direct action by the ghost to achieve a violent revenge is unprecedented in the history of our text," Fowler writes. "In other ballads, ghosts do tear their victims [...] but up to this point, there has been no hint of such a practice in The Gosport Tragedy."

There's something very appealing about the dead girl being given this far more active role in her killer's demise. William's old "raving" death simply couldn't compete, and was almost instantly replaced by the new scene. Oxford's Bodleian Library has 16 ballad sheets telling The Gosport Tragedy's story in its collection, all produced between 1815 and 1885. Some call the truncated song Love and Murder, some call it Polly's Love and some call it The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, but every one of them gives the ghost its expanded and more vicious role.

Those sheets' original buyers would have gained an extra little shiver from the number of pieces Polly selects for her lover's corpse. Three was a number often encountered in beliefs about demonology at the time, which presumed the Devil and his agents used it as a means of mocking the Holy Trinity. Satan, it was said, knocked three times on the door before coming to claim your soul, so giving that number a part to play in Billy's death made the ghost more frightening than ever.

Fowler's a bit sniffy about the new verse, calling the folk process which he assumes produced it "a species of alchemy which converts gold to lead". For my money, though, it brings a welcome touch of added drama to the song, and all the more so once a tidy little internal rhyme had been added. (23)

"She ripped him and she stripped him and she tore him in three," Peter Bellamy sings in his 1969 recording. I'm not sure when that phrasing was introduced, but it's now become a fixture in its own right, appearing also in recordings by Waterson:Carthy in 2009 and Jon Boden two years later. Boden included the song in his 2011 A Folk Song A Day project and adds a note there applauding the fact that it gives Polly such a satisfying revenge.

The fact that we have so many surviving copies of this song's various ballad sheets is testament to just how many were produced, and hence of how popular the song remained. They also allow us to trace quite small details of its development through the years, as various ballad shops polished up the verses' logic and flow from one edition to the next. Take this rather awkward line, which we can watch being gradually improved over a spell of about 20 years:

There's a murderer on board has lately been done. (Pitts, London, circa 1831).

There's a murderer on board, he has it lately done. (Hodges, London, circa 1850).

There's a murderer on board, and he must be known. (Harkness, Preston, circa 1853).

As this process continued in Britain, copies of the original ballad were still being produced in America. The earliest version we have printed on that side of the Atlantic is titled The Gosport Tragedy and appears in a collection called The Forget-Me-Not-Songster, editions of which were produced in Boston, Philadelphia and New York. The particular copy I'm looking at here comes from a Boston print shop called Deming's, and has been dated to about 1835. (24)

We don't know quite when the song first appeared in America, but Fowler suggests one interesting route that may have got it there. The Bedford served a second tour of duty in the Baltic in 1727, with Charles Stewart once again on board, returning to Portsmouth in August of that year for a month's stay in its home port. "During this time, the Bedford sent 38 men to Gosport Hospital, and we know that one of them was Charles Stewart," Fowler writes. "The musters show that he left the ship on 26 August and returned from Gosport on 8 September." Throughout this period Stewart, like the other men sent for treatment has the letters "ss" noted against his name to indicate "sick on shore".

Fowler identifies the hospital used as Forton Hospital at Gosport, which had also treated some of Hook's men after the Bedford's 1726 expedition. Just 50 years after Stewart's stay there, the British Navy needed somewhere to house its captives from America's Revolutionary War, and turned Forton Hospital into a POW camp.

"Thanks to the preservation of a journal and songbook kept by American prisoners there, we know a great deal about life in Forton Prison in Gosport during the Revolution, including some of the songs they sang" Fowler writes. "Unfortunately, The Gosport Tragedy is not preserved in the American songbook of 1778, but the existence of this collection, which includes British as well as American songs, suggests one path by which our ballad may have found its way to America."

Our first American text for the song - let's call it the Deming Gosport - starts by naming its characters William and Molly, then switches to calling the girl Mary half-way through from what seems to be sheer carelessness. It takes a leisurely 108 lines to tell the story in its traditional form, frankly describing Molly's unwanted pregnancy and with William raving himself to death rather than being torn to pieces by the ghost. The ship he flees to is not named, but it's said to be preparing to "set sail from Plymouth to plough the salt sea". Plymouth is another British naval city, about 150 miles west along the coast from Portsmouth, and I imagine it's just the similarity of the two names which accounts for this confusion. (25)

"Prints like the Boston one helped keep the American version alive," Fowler writes. "This, together with some form of the shorter version known as The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, combined to determine the future development of the ballad in American oral tradition." The Deming Gosport's main contribution to that development comes in the new wording it introduces for some key scenes.

Often, that wording would remain in place for well over a century. As William's lining Molly up for her fatal walk in the woods, for example, the Boston sheet makes his promise of marriage more explicit than ever: "And if that tomorrow, my love will ride down / The ring I can buy our fond union to crown". That couplet was still appearing as late as 1962, when the Canadian Leo Spencer phrased it as: "If it be tomorrow, and you will come down / A ring I will buy you worth one hundred pound."

When it all goes wrong and Molly's begging for her life, it's not her the Deming Gosport describes as "so comely and fair", but her assassin. This idea appears again in a 1957 recording of Pretty Polly by the Kentucky banjo player Pete Steele, which Sparks singles out in her 2005 essay on the song. "He calls Pretty Polly's murderer 'Pretty Willy'," she writes. "They are both beautiful - the killer and the killed."

When it all goes wrong and Molly's begging for her life, it's not her the Deming Gosport describes as "so comely and fair", but her assassin. This idea appears again in a 1957 recording of Pretty Polly by the Kentucky banjo player Pete Steele, which Sparks singles out in her 2005 essay on the song. "He calls Pretty Polly's murderer 'Pretty Willy'," she writes. "They are both beautiful - the killer and the killed."

The Deming Gosport's re-imagining of William's confrontation on board ship is particularly striking, swapping the English ballad's somewhat stilted language for a far more conversational tone. Stewart reports his own ghost sighting to the captain, and then:

The captain soon summoned the jovial ship's crew,

And said "My brave fellows, I fear some of you,

Have murdered some damsel 'ere you came away,

Whose injured ghost haunts you now on the sea.

"Whoever you be, if the truth you deny,

When found out, you'll be hung on the yard-arm so high,

But he who confesses, his life we'll not take,

But leave him upon the first island we make".

Then William immediately fell on his knees,

The blood in his veins quick with horror did freeze,

He cried "Cruel murder! Oh, what have I done?

God help me, I fear my poor soul is undone."

The traditional verses resume at this point, explaining that William's the only one glimpsing the ghost this time, describing his lonely death and getting Molly's remains properly interred at Gosport in just 12 swift lines.

By 1850, after a century or more in print, The Gosport Tragedy was familiar enough to make it worth parodying in London's music halls. A version called Molly The Betrayed or The Fog Bound Vessel was produced for the comic singer Sam Cowell. The ballad shops quickly printed up sheets using Cowell's lyrics, hoping to capitalise on the popularity of his performance, and by 1855 it had some official sheet music too.

Cowell had begun his stage career as a child, touring America in various Shakespeare plays with his actor father. Sometimes, he would perform 'coon' songs front of curtain to keep the audience entertained while scenery was being changed behind him. Returning to England in about 1840, and still just 20 years old, he decided there was more money in this burlesque side of his act and ditched the Bard to make room for more comic songs.

"By 1850, he had abandoned the legitimate stage entirely in favour of the songs and supper rooms of the West End," says The Cambridge Guide to American Theatre. "An ugly little man with a lugubrious expression, he specialised in cockney song-and-patter acts."

And that's exactly what Molly The Betrayed is. Spelling out its words phonetically in an attempt to mimic Cowell's bizarre stage accent, the parody tells the same core story as The Gosport Tragedy but mixes its narrative passages with a string of silly jokes. Its targets include the ballad sheets' sometimes rather strained rhymes, their reliance on highly melodramatic plots and the conventions of rural folk songs at the time. (26)

This last element suggests audiences in 1850 were just as likely to have encountered the original tale in its folk song form as they were to have found it on a printed ballad. Certainly, Molly The Betrayed would have meant nothing to anyone who didn't already know the original song in one form or another, which testifies again how popular it had become.

What emerges from all this is something very like the comic monologues Stanley Holloway made famous in the 1930s. A few extracts will give you its flavour:

In a kitchen in Portsmouth, a fair maid did dwell,

For grammar and grace none could her excel,

Young William, he courted her to be his dear,

And he by his trade was a ship's carpen – tier.

Singing doodle, doodle chop, chum, chow choral li la.

Now it chanced that von day, ven her vages vos paid,

Young Villiam valked vith her and thus to her said,

"More lovely are you than the ships on the sea",

Then she hugged him and laughed, and said"Fiddle-de-dee".

[...]

Then up came the captain with "Unfurl every sail",

He guv'd his command, but to no avail,

A mist on the hocean arose all around,

And no vay to move this fine ship could be found.

[...]

Then he calls up his men with a shout and a whoop,

And he orders young Villiam to stand on the poop,

"There's summat not right," he says, "'mongst this here crew,

And blowed if I don't think, young Villiam, it's you".

Then Villiam turned vite and then red and then green,

Vile Molly's pale ghost, at his side it was seen,

Her bosom vas vite, the blood it vas red,

She spoke not but vanished, and that's all she said.

This version added a fifth title to the song's growing collection. Already, it was variously known as The Gosport Tragedy, The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, Love and Murder and Polly's Love, but now Molly The Betrayed joined the list as well. The first evidence we have of it taking the name we know today comes in another parody, which seems to have been current in the 1890s.

That's when a woman identified only as Mrs MM says she learned the song she performed for collectors at her Missouri home in August 1938. She called this song Pretty Polly, and its four verses form a bawdy parody of our own ballad:

"Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, oh won't you come to me,

Pretty Polly, Pretty Polly, oh won't you come to me,"

"Oh no, my young man, I'm afraid you'll undo me,

Oh lay your leg over me do."

Her drawers they was tied and he couldn't undo 'em,

Her drawers they was tied, and he couldn't undo 'em,

She snorted and cried "Just take your knife to 'em,

Oh lay your leg over me, do."

And then they began like lighnin' and thunder,

And then they began like lightnin'and thunder,

On the green, green grass, with Polly layin' under,

"Oh lay your leg over me, do."

In about nine months, Polly went to weepin'

In about nine months, Polly went to weepin'

And then she remembered that crawlin' and creepin',

"Oh lay your leg over me do."

The structure there is very much like Pretty Polly's and the opening lines are almost identical. Both songs include a knife, both have Polly weeping at some point along the way, and both give her an unwanted pregnancy. The fact that Mrs MM knew her song as Pretty Polly, coupled with the very prominent use of that phrase in its opening lines, suggests the real ballad may already have adopted that name when the parody was produced. If so, no printed copy seems to have survived.

The structure there is very much like Pretty Polly's and the opening lines are almost identical. Both songs include a knife, both have Polly weeping at some point along the way, and both give her an unwanted pregnancy. The fact that Mrs MM knew her song as Pretty Polly, coupled with the very prominent use of that phrase in its opening lines, suggests the real ballad may already have adopted that name when the parody was produced. If so, no printed copy seems to have survived.

More reliable evidence emerged in 1917, when the English song collector Cecil Sharp heard an unusual version in North Carolina. Sharp had already expressed some interest in The Gosport Tragedy, saying in 1907 that it was one of the few supernatural folk ballads still popular among the rural singers he interviewed. (27)

Sharp's North Carolina find was titled The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, and sung with a new twist to William's death:

He entered his ship on the salt sea so wide,

And swore by his maker he'd see the other side,

While he was a-sailing in his heart's content,

The ship sprang a leak: to the bottom she went.

While he was a-lying there, all in sad surprise,

He saw Pretty Polly appear before his eyes,

"Oh William, oh William, you've no time to stay,

There's a debt to the devil that you're bound to pay".

William's victim had first been called Polly almost a century before, and retained that name on and off ever since. If you discount the Missouri parody, then Sharp's is the earliest version I've seen to call her "Pretty Polly" in full. Once Molly became Polly on that 1822 Liverpool sheet, the temptation to attach "Pretty" in this way was always going to prove irresistible. The fact that several unconnected folk songs sometimes called themselves Pretty Polly already did not prevent our own ballad being re-titled in her honour. (28)

Song collectors still find the odd American version calling the girl Molly rather than Polly today - another reminder of the song's roots - but these are very much the exception rather than the rule. Less than a decade after Sharp noted down the lyrics above, the song's first commercial discs appeared. By 1927, John Hammond, BF Shelton and Dock Boggs had all released recordings of the song they called Pretty Polly, and all its earlier names simply dropped away.

The first man to put Pretty Polly on disc was John Hammond, who cut it for Gennett Records at a Richmond, Indiana session in April 1925. Gennett stressed his roots as an East Kentucky banjo player by calling the song Purty Polly on its 1927 release.

Hammond's lyrics show that the process of Americanising Pretty Polly still had some way to go. He sets the story in London for a start, and allows himself a leisurely 11 verses to get it told. No trace of the maritime setting remains, but there's still the odd line which retains a flavour of English folk songs, such as his description of Polly "with her rings on her fingers and lily-white hands". Others carry a distinct whiff of American puritanism: "A love of her body has sent her soul to hell".

This last element is characteristic of many American adaptations of British songs, which often erase their source ballads' frank acknowledgement that an unwanted pregnancy caused all the trouble. Hammond comes as close as he dares to suggesting Polly's indiscretion in his fourth verse:

"Come and go Pretty Polly, come go along with me,

Come and go Pretty Polly, come go along with me,

Before we get married, there's pleasure to see."

In the English ballads, which spell out the nature of that pleasure elsewhere, Willie needs only to tell Polly that he wants them to visit some friends. The much shorter American song has to make each verse work that bit harder, though, and Hammond's coinage is a clever way of nodding towards sex while also allowing him to insist that wasn't what he had in mind at all.

Two other banjo players released their own versions of Pretty Polly in 1927, and both were as careful as Hammond to skirt around this sensitive issue. BF Shelton, another Kentucky native, and Dock Boggs from the next-door state of Virginia, both use the "pleasure to see" verse, but only Shelton gives this additional hint of what Willie and Polly have been up to:

"I courted Pretty Polly one live-long night,

I courted Pretty Polly one live-long night,

And left the next morning before it was light."

All this careful evasion falls a long way short of The Gosport Tragedy's unblinking gaze: "At length with his cunning he did her betray / And to lewd desire he led her away". It takes quite a determined search of Pretty Polly's lyrics to reveal even a hint of that idea in the American song, and for most casual listeners the result is that Polly herself emerges as a rather baffled virgin.

"Who can ever completely explain the cringing terror that made us remove all references to sex in Pretty Polly?" Sparks asks. "Our Polly is a mannequin, and an empty shell. [...] She's too weak to lift her arms in an embrace. Her lips are too slack to kiss. She can only be entered with a knife." Later she adds: "Our Polly seems utterly unaware of sex. She does, however, know a grave when she sees one. Her only sin is recognising her grave, having knowledge of death. In America, this may be sin enough."

The most obvious manifestation of this idea comes in the song's "spade lying by" verse, which is a direct transplant from the English original. Hammond shies clear of that stanza, but replaces it with a suggestion that Willie is somehow testing Polly as they walk through the woods:

He led her over hills and valleys so deep,

He led her over hills and valleys so deep,

Polly, she mistrusted, and then began to weep.

For Sparks, this is the moment when Polly realises her faith in Willie is unjustified, and it's witnessing this loss of her innocence which finally resolves him to kill her. The switch in Willie's head flips from "madonna" to "whore", and in that instant his virgin Eve is banished from the Garden. "I sometimes wonder if Pretty Polly might have lived if only she had looked at her grave and seen an innocent hole in the ground," Sparks says. "The knowledge that kills her is the knowledge of life and death."

Far from weakening its impact, Pretty Polly's terror of sex makes it a much more mysterious and haunting song than The Gosport Tragedy ever was. "Like the wordless unspeakable parts of our own psyche, murder ballads hold secrets that loom larger the further down they're pushed," Sparks says. "Pretty Polly only gained magic as we whittled her down and wrapped her in veils."

That's unquestionably true. By avoiding any hint that Willie's victim was pregnant, the American song removes all clues to his motive for killing her, and so denies us the chance to neatly rationalise his crime away. In the American song, Willie kills for no reason at all, and seems to consider it a trivial act. That makes him a far scarier figure than his English ancestor.

That's unquestionably true. By avoiding any hint that Willie's victim was pregnant, the American song removes all clues to his motive for killing her, and so denies us the chance to neatly rationalise his crime away. In the American song, Willie kills for no reason at all, and seems to consider it a trivial act. That makes him a far scarier figure than his English ancestor.

In 1938, The Coon Creek Girls became the first women to record Pretty Polly. They were a string band led by Lily May and Rosie Ledford, a pair of Kentucky sisters recruited to provide music for an Ohio country music station. Their rendition sticks too closely to their male predecessors' lyrics to offer any striking new perspective, but they were the first recording artists to let Polly speak for herself as Willie draws his blade:

"Oh Willie, oh Willie, please spare me my life,

Oh Willie, oh Willie, please spare me my life,"

So deep into her bosom he plunged that fatal knife.

Lily May Ledford sings most of the rest from Willie's point of view, showing no greater empathy with Polly than any of the male singers had managed. She's certainly a good deal tougher than Dock Boggs, who coyly insists that the dead Polly has merely "fell asleep" in his own version. (29)

The Stanley Brothers recording followed in 1950, underpinning Ralph Stanley's high lonesome vocals with a stately stand-up bass to fatten out the sound. It's notable not only for the slurs on Polly's past reputation which we've already discussed, but also for a masterly bit of misdirection in the opening verses, which depict Willie as a rather gentle figure:

"Oh Polly, Pretty Polly, would you take me unkind,

Polly, Pretty Polly, would you take me unkind,

Let me sit down beside you and tell you my mind.

"Oh my mind is to marry and never to part,

My mind is to marry and never to part,

The first time I saw you, it wounded my heart."