Ballad shops all over the UK continued to produce sheets with The Gosport Tragedy's tale right through the 19th century, often adding small improvements to the scansion or cutting its length as they went.

Ballad shops all over the UK continued to produce sheets with The Gosport Tragedy's tale right through the 19th century, often adding small improvements to the scansion or cutting its length as they went.

In some cases, these refinements may have begun in the song's oral tradition, as singers passed it from mouth to mouth and it slowly evolved in response. When that happened, the balladeers had only to transcribe what they'd already heard sung in the streets, but in other cases they'd be composing their own verses from scratch. Whatever its source, the most significant change came when someone decided William was getting off rather too easily in the original song. What was needed here, they felt, was for someone to give him a far nastier death.

It's possible that this change appeared as early as 1805, but the earliest concrete example I've been able to find is a Liverpool sheet produced around 1822. This retitles the ballad Love and Murder, cuts it to just 44 lines, and sets its action in the English town of Worcester. The story is just as we know it, but the girl's name has now morphed from Molly to Polly. Her killer is called Billy, and his entire life after escaping to the ship is condensed into the ballad's final three verses:

One morning before ever it was day,

The captain came up, and this he did say:

"There is a murder on board that has lately been done,

Our ship is in mourning, we cannot sail on".

Then up stepped one: "Indeed it's not me",

Then up steps another: "Indeed it's not me",

At length up steps Billy, and this he did swear:

"Indeed it's not me, I vow and declare".

As he was running from the captain with speed,

He met with his Polly which made his heart bleed,

She stripped him and tore him, she tore him in three,

Because that he murdered her baby and she.

"This direct action by the ghost to achieve a violent revenge is unprecedented in the history of our text," Fowler writes. "In other ballads, ghosts do tear their victims [...] but up to this point, there has been no hint of such a practice in The Gosport Tragedy."

There's something very appealing about the dead girl being given this far more active role in her killer's demise. William's old "raving" death simply couldn't compete, and was almost instantly replaced by the new scene. Oxford's Bodleian Library has 16 ballad sheets telling The Gosport Tragedy's story in its collection, all produced between 1815 and 1885. Some call the truncated song Love and Murder, some call it Polly's Love and some call it The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, but every one of them gives the ghost its expanded and more vicious role.

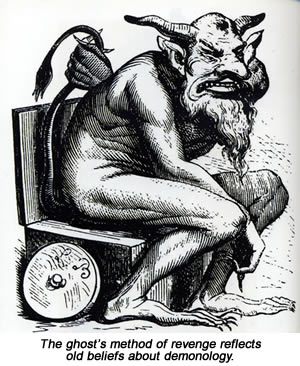

Those sheets' original buyers would have gained an extra little shiver from the number of pieces Polly selects for her lover's corpse. Three was a number often encountered in beliefs about demonology at the time, which presumed the Devil and his agents used it as a means of mocking the Holy Trinity. Satan, it was said, knocked three times on the door before coming to claim your soul, so giving that number a part to play in Billy's death made the ghost more frightening than ever.

Fowler's a bit sniffy about the new verse, calling the folk process which he assumes produced it "a species of alchemy which converts gold to lead". For my money, though, it brings a welcome touch of added drama to the song, and all the more so once a tidy little internal rhyme had been added. (23)

"She ripped him and she stripped him and she tore him in three," Peter Bellamy sings in his 1969 recording. I'm not sure when that phrasing was introduced, but it's now become a fixture in its own right, appearing also in recordings by Waterson:Carthy in 2009 and Jon Boden two years later. Boden included the song in his 2011 A Folk Song A Day project and adds a note there applauding the fact that it gives Polly such a satisfying revenge.

The fact that we have so many surviving copies of this song's various ballad sheets is testament to just how many were produced, and hence of how popular the song remained. They also allow us to trace quite small details of its development through the years, as various ballad shops polished up the verses' logic and flow from one edition to the next. Take this rather awkward line, which we can watch being gradually improved over a spell of about 20 years:

There's a murderer on board has lately been done. (Pitts, London, circa 1831).

There's a murderer on board, he has it lately done. (Hodges, London, circa 1850).

There's a murderer on board, and he must be known. (Harkness, Preston, circa 1853).

As this process continued in Britain, copies of the original ballad were still being produced in America. The earliest version we have printed on that side of the Atlantic is titled The Gosport Tragedy and appears in a collection called The Forget-Me-Not-Songster, editions of which were produced in Boston, Philadelphia and New York. The particular copy I'm looking at here comes from a Boston print shop called Deming's, and has been dated to about 1835. (24)

We don't know quite when the song first appeared in America, but Fowler suggests one interesting route that may have got it there. The Bedford served a second tour of duty in the Baltic in 1727, with Charles Stewart once again on board, returning to Portsmouth in August of that year for a month's stay in its home port. "During this time, the Bedford sent 38 men to Gosport Hospital, and we know that one of them was Charles Stewart," Fowler writes. "The musters show that he left the ship on 26 August and returned from Gosport on 8 September." Throughout this period Stewart, like the other men sent for treatment has the letters "ss" noted against his name to indicate "sick on shore".

Fowler identifies the hospital used as Forton Hospital at Gosport, which had also treated some of Hook's men after the Bedford's 1726 expedition. Just 50 years after Stewart's stay there, the British Navy needed somewhere to house its captives from America's Revolutionary War, and turned Forton Hospital into a POW camp.

"Thanks to the preservation of a journal and songbook kept by American prisoners there, we know a great deal about life in Forton Prison in Gosport during the Revolution, including some of the songs they sang" Fowler writes. "Unfortunately, The Gosport Tragedy is not preserved in the American songbook of 1778, but the existence of this collection, which includes British as well as American songs, suggests one path by which our ballad may have found its way to America."

Our first American text for the song - let's call it the Deming Gosport - starts by naming its characters William and Molly, then switches to calling the girl Mary half-way through from what seems to be sheer carelessness. It takes a leisurely 108 lines to tell the story in its traditional form, frankly describing Molly's unwanted pregnancy and with William raving himself to death rather than being torn to pieces by the ghost. The ship he flees to is not named, but it's said to be preparing to "set sail from Plymouth to plough the salt sea". Plymouth is another British naval city, about 150 miles west along the coast from Portsmouth, and I imagine it's just the similarity of the two names which accounts for this confusion. (25)

"Prints like the Boston one helped keep the American version alive," Fowler writes. "This, together with some form of the shorter version known as The Cruel Ship's Carpenter, combined to determine the future development of the ballad in American oral tradition." The Deming Gosport's main contribution to that development comes in the new wording it introduces for some key scenes.

Often, that wording would remain in place for well over a century. As William's lining Molly up for her fatal walk in the woods, for example, the Boston sheet makes his promise of marriage more explicit than ever: "And if that tomorrow, my love will ride down / The ring I can buy our fond union to crown". That couplet was still appearing as late as 1962, when the Canadian Leo Spencer phrased it as: "If it be tomorrow, and you will come down / A ring I will buy you worth one hundred pound."