This new PlanetSlade book - my fourth - contains all the gallows ballads essays which once filled this section of the site. I've kept them all available as free online pieces for well over ten years, but now I'm asking people to buy the book instead.

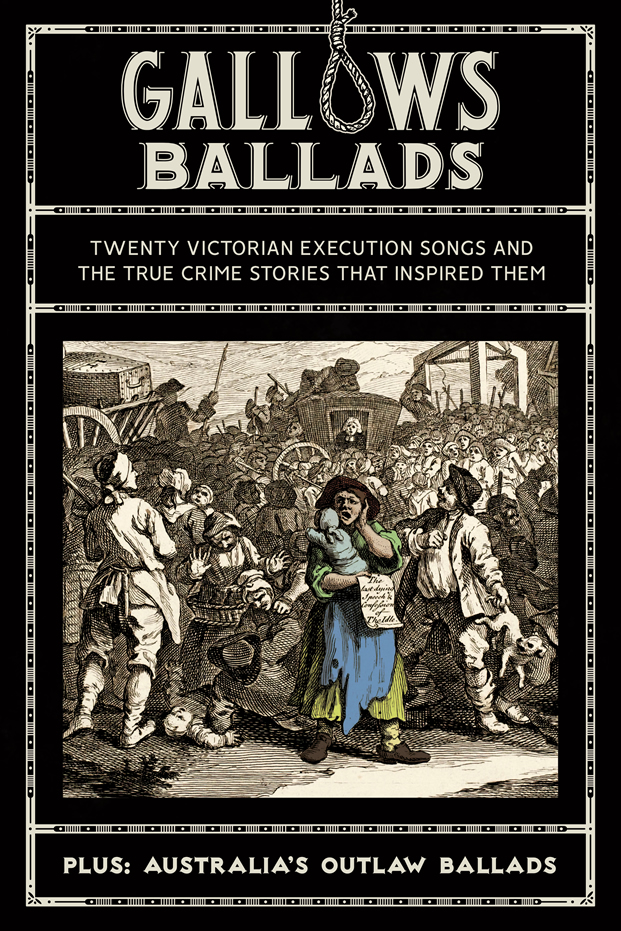

Gallows ballads were the cheap, one-sheet publications knocked out by jobbing print shops for sale to the eager spectators at Britain's regular public hangings. Typically, they'd include a lurid account of the condemned man's crime, plus a set of ballad verses describing his downfall in song. Though often presented as the killer's own words, these "last goodnights" were actually produced by a freelance band of seedy but prolific hacks.

Beginning with an essay explaining the nuts and bolts of this trade and introducing a couple of the colourful rogues who ran it, the book goes on to cover 20 individual ballad sheets chosen from the British Library's collection. Each song appears with its full lyrics and my extensive research on the true crime story which inspired it. PlanetSlade readers took up my invitation to set these old lyrics to their own music and perform them once again as living songs. The book has all the links you'll need to hear the 29 recordings this produced - the best of which are very good indeed.

Later in the volume, I've added a lengthy section looking at Australia's vintage bushranger ballads and their continuing influence on the country's rebel music today. Jack Donohoe and Ben Hall are two of the outlaws whose songs figure there. Finally, I like to include something in each book that's never appeared anywhere else at all, and in this case it's my short play set in an 1853 London print shop. The week's big hanging is approaching fast, but Jemmy Catnach's star writer has let him down...

All these delights can now be yours in either paperback or e-book form for the price of a couple of drinks. Head over to Amazon US or Amazon UK to buy your copy now!