Russell Taylor and Charles Peattie's daily cartoon strip Alex has been a constant presence in Britain's national press for over 25 years, producing stage and radio versions of the character's exploits and winning his creators a couple of MBEs along the way. Of all the British newspaper strips still being produced by their original creators, only Steve Bell's If. can boast a longer run. (1, 2)

Russell Taylor and Charles Peattie's daily cartoon strip Alex has been a constant presence in Britain's national press for over 25 years, producing stage and radio versions of the character's exploits and winning his creators a couple of MBEs along the way. Of all the British newspaper strips still being produced by their original creators, only Steve Bell's If. can boast a longer run. (1, 2)

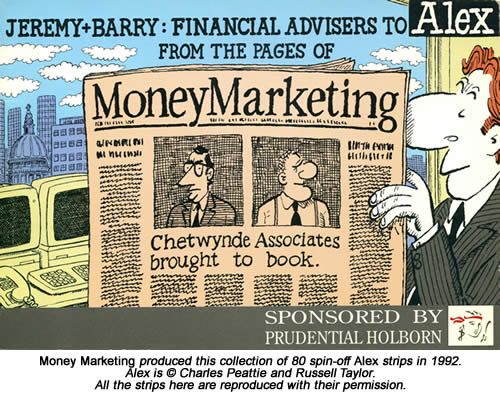

Few people realise, however, that Russell and Charles also produced a series of 80 spin-off Alex strips, running from 1989 to 1992 in a weekly trade paper called Money Marketing. I know this because I was working for MM at the time and managed to worm my way into a small part of the spin-off strip's production process.

Once a month or so, Russell would forgo his usual routine of plush City lunches to enjoy a cup of foul vending machine coffee in our meeting room, where MM news editor Caroline Merrell and I would brief him on whatever issues were exercising the paper's readers that week. Those briefings would give Russell his fodder for the spin-off strip's next two or three gags, which Charles duly drew up for publication a few days later. For a comic strip nerd like me, even this peripheral role in the process was a lot of fun. Once in a while, I'd even get to visit the duo in their garret studios just north of Oxford Street or corner Russell in the pub to drone on about my own favourite strips.

The MM project began in early 1989, by which time the real Alex strip had been running for about two years, first in Robert Maxwell's London Daily News and later in The Independent. Both papers ran the strip on their financial news pages and it quickly built up a following among the real City professionals who Alex's obsessions with cash and status set out to parody. Russell had cultivated a lot of contacts at every level of City life, who were flattered enough by the attention that Alex gave their world to brief him on the scandals of the day from their own insider perspective.

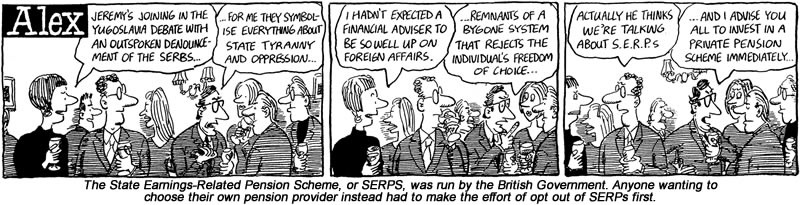

It didn't seem to matter that Alex himself was a far from sympathetic character. "A 25-year-old high-finance whizz kid, he has all the attributes of upwardly mobile living," the strip's first book collection explains, "and an instinctive intolerance for all those poorer or less successful than himself." No-one among Alex's real life counterparts would own up to such traits in themselves, of course, but everyone could point to someone at the next desk who certainly had them. This balancing act of accurately skewering City habits without alienating their key sources was one Russell and Charles pulled off very adroitly, and it wasn't long before someone at Prudential Holborn started wondering if they could repeat the trick with a sponsored strip aimed at Independent Financial Advisers. (3)

These bods, known for short as IFAs, were the people who actually read Money Marketing and they formed an important distribution channel for Pru Holborn to sell its funds. IFAs dealt not with the City high-fliers Alex encountered, but with the general public, selling pensions, life insurance and unit trusts to anyone with a few thousand quid to invest and just enough savvy not to rely on the High Street banks alone. By sponsoring a spin-off Alex strip in their paper, Pru Holborn hoped to keep its name in front of these IFAs in a relatively subtle, classy way. Terms were agreed and Russell duly turned up at our offices to see what jokes it might be possible to extract from the IFA sector's peculiar little world.

"The good thing about doing cartoons for industry magazines is that you can write about 100 jokes straight off on the subject of cosmetic dentistry or garden furniture or whatever, just utilising all the basic concepts and puns that arise from that particular profession," Russell told me. "As Alex's annoying American boss Cyrus would say, you'd be plucking the low-hanging fruit - and you'd be the only plucker doing it.

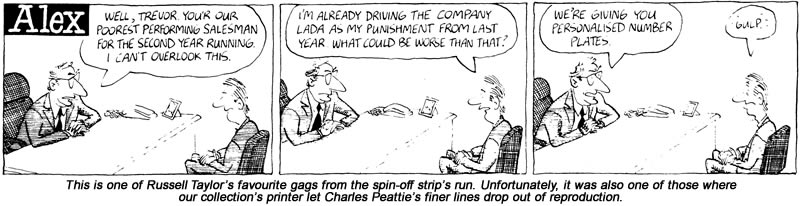

"The practitioners in the industry you're writing jokes about, whether they're prosthetic limb manufacturers or market gardeners, are so delighted and grateful at the fact that their humble and obscure profession is considered worthy of satire that you can also flog your artwork to conferences and for boardrooms and executive loo walls. Many years ago, the cartoonist Ken Pyne did a cartoon about a builders' convention, in which he depicted all the delegates with their bums hanging out of their trousers. He told me once he'd redrawn that cartoon maybe 20 times to sell to different people in the construction trade." (4, 5)

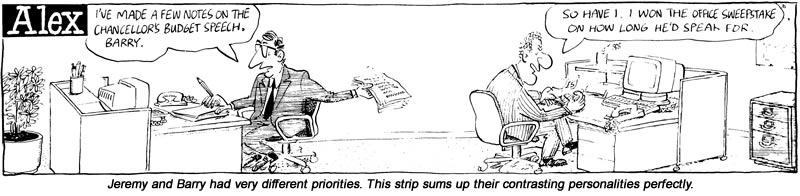

IFAs at that time were still getting used to the new rules imposed on them by 1986's Financial Services Act and ranged across the whole spectrum from conscientious professionals to unabashed old-school salesmen. At our first meeting with Russell, it was quickly decided that the new strip should feature one IFA from each end of this spectrum and that's how Jeremy Chetwynde and his partner Barry Jackson were born. Jeremy was hard-working, keen on business ethics and determined to lift his profession to the same standards as a prestigious law or accountancy practice. Barry was hard-sales all the way, chasing commission with the ferocity of a rottweiler and utterly shameless about cold-calling even the most unlikely prospect.

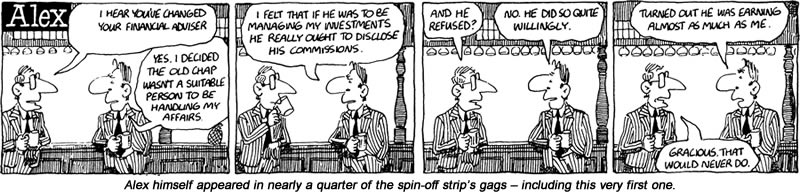

Pru Holborn was keen to use the Alex brand on its new strip, so it was agreed that Jeremy and Barry could be the two minions our hero employed to wade through the unit trust performance tables for him while he was networking at the opera. That had the added bonus of allowing Alex himself to make an appearance in the MM strip from time to time and gave us ample excuse to feature him on the book cover above.

Alex gave us his own perspective on his two advisers' contrasting personalities when Russell persuaded him to dictate an introduction for our 1992 collection of the MM strips. "Jeremy Chetwynde was at school with my father and I've known him since I was knee high," he wrote. "Throughout my youth, he always gave me the benefit of his financial know-how, discouraging me from frittering away my pocket money on Captain Scarlet bubble gum and ensuring I was the only 12-year-old to be wiped out in the secondary banking crisis of the mid-70s.

"His partner Barry Jackson is of somewhat different mettle. Looking like he might be more at home flogging off remaindered Robochefs in a repossessed showroom on Oxford Street, Barry is one of the new breed of IFAs who thrived in the aggressive market conditions of the 80s. By all accounts he was rather a tearaway in his youth. But he now rues those wasted years of playing truant from school, as it has left him an annoying shortage of old classmates to cold-call." (6)

"I have a theory that there are only two essential comedy characters: the bully and the wimp," Russell says. "Many comedic situations involve cruelty or insensitivity and therefore the basic dramatis personae tend to be the perpetrator and the victim of that cruelty. So it was probably no surprise that the two characters who emerged confirmed to these prototypes. Jeremy was the posh, effete and hapless one, while Barry was streetwise, ruthless and materialistic. In many ways, they were just different incarnations of Alex and Clive in the main strip."

Barry was such a colourful character that he came to dominate the strip more and more as time went on. He was based on a real IFA I'd interviewed shortly after the paper launched in 1985, who'd quickly got frustrated with my naïve questions and treated me to a no-holds-barred account of what it took to survive in his Willy Loman world. This developed into a hugely entertaining tirade, almost none of which was usable in print. Still, I knew this guy was too good to waste, so I was delighted when Russell decided to give him a doppelganger in the strip.

Once we'd decided on the characters and given Russell just enough background to place them in a convincing setting, he went off to concoct the first couple of gags and I was given the job of writing a jokey profile of Alex himself to run in Money Marketing. Even after only two years in print, Alex was already a very well-known strip, so nabbing its first spin-off was something of a coup for the paper and we wanted to crow about it a bit. You can read the profile for yourself as a PDF here.

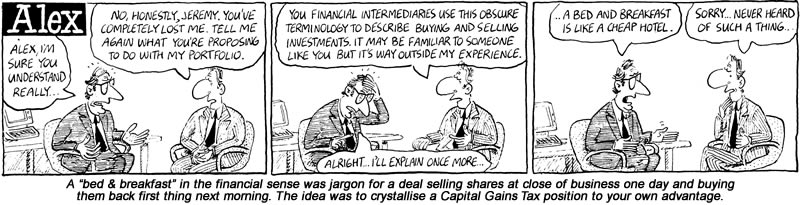

For the next three years, Russell would come into Money Marketing's Soho offices once a month of so for us to tell him about whatever industry scandals and rows were in progress at the time. Most of the issues we described for him were far too convoluted to ever be compressed into a three-panel gag strip, but once in a while we'd unthinkingly blurt out a bit of industry jargon which he did find useful. The "bed & breakfast" strip above is my favourite example of these particular gags, because it's so true to Alex's character. It makes perfect sense that he'd be at home with this phrase as stockmarket slang, but completely baffled by the notion of an inexpensive hotel.

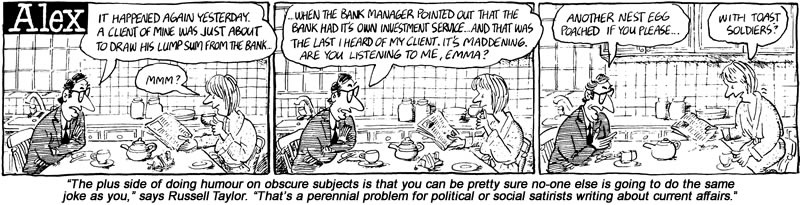

In one way, Russell found that writing the MM strip was actually easier than writing Alex jokes about the City. One problem with the main strip was that some of the jokes proposed were so technical in nature that no-one outside a few dozen very specialist City folk could be expected to understand them. Even on its financial pages, a national newspaper had to appeal to a far wider audience than that, so these were the ideas he always rejected.

The beauty of writing gags for Money Marketing, on the other hand, was that all the paper's readers were directly involved in the IFA trade. That meant Russell could safely assume they already knew all the background needed to chuckle over gags about the Fimbra council or the amount of booze supped on the industry's leading conference cruise. "Being a cartoonist is a strange outlet for humour in that, unlike a stage comedian, you rarely get to see the reaction of the audience," he told me. "You just have to hope that they liked your joke. Of course, it's even stranger when you have to take someone else's word for it that the joke is funny in the first place."

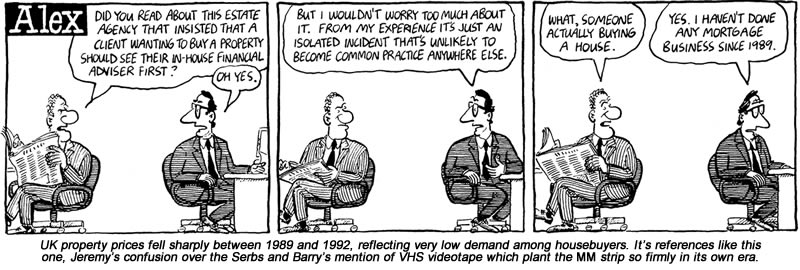

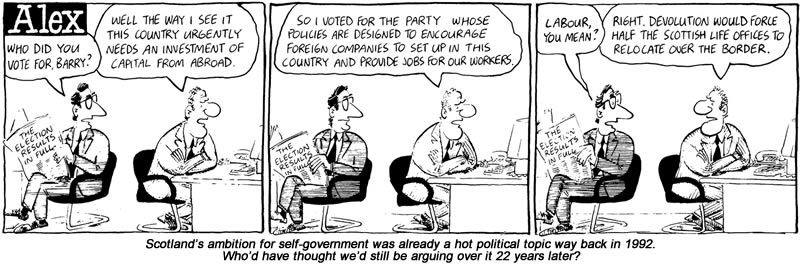

The Money Marketing strip came to an end after about three years - the rumour at the time being that Pru Holborn had wanted to give Russell and Charles a pay cut which they refused to accept. We produced the book shown here collecting all 80 MM strips as a little giveaway for the paper's 1992 Christmas party and then just drew a line under the whole thing. Somewhere in cartoon limbo, I like to think Jeremy and Barry are still beavering away: flogging a pension to Sam Lark, perhaps, or persuading Wellington he needs pet insurance for Boot. (7)

"There is an irony in noting that what Jeremy and Barry were doing in the late eighties/early nineties was flogging the financial products that have, 25 years later, occasioned the £30bn or so of provisions British banks have had to put aside as compensation payments for mis-selling," says Russell. "Somehow, it gives the strip a retrospective satirical significance. It turns out that what we were writing about was far more relevant than we (or any of Chetwynde Associates clients) realised at the time.

"One of the more popular Alex strips we've published recently in The Daily Telegraph involved Alex throwing a party to celebrate his 50th birthday. What he didn't want his guests to find out was that he had paid for the party with the miserable proceeds of an endowment policy he had taken out in the mid-eighties. It was supposed to pay off his mortgage and give him a handsome retirement income, but in reality just funded a few bottles of champagne and some canapés. That useless financial product would, of course, have been sold to him by Jeremy and Barry."

You can follow Alex every day on Peattie & Taylor's own alexcartoon.com or on The Daily Telegraph's website. Apologies to Charles Peattie for reproducing some of his art so badly here. Both the sites I've just linked to do a far better job.

Sources & Footnotes

1) If. made its debut in 1981, six years before Alex's first appearance. As of January 28, 2014, If. had published a total of 7,177 strips against Alex's 6,273.

2) Reporting these figures to Russell, I pointed out that Alex's greater frequency meant he and Charles were slowly reducing Bell's lead. "He's still beating us," Russell replied. "By my maths, I reckon it would take us another 20 years to overhaul him and I can't face doing this job till I'm 75."

3) Alex, by Peattie & Taylor (Kingswood Press, 1987).

4) Exchange of e-mails, February 2014.

5) You can find Ken Pyne's builders cartoon by scrolling down the Procartoonists site here.

6) Jeremy & Barry: Financial Advisers to Alex, by Charles Peattie and Russell Taylor (Centaur Communications, 1992).

7) The Larks and The Perishers (where Wellington and his dog Boot appeared) are two other long-dead British newspaper strips.