"After shooting Glover to death, the mob brought his body to Macon and threw the corpse in the lobby of the Douglass Theatre, near the scene of the crime. The police finally rescued it from the crowd of whites, both men and women, who thronged the place."

"After shooting Glover to death, the mob brought his body to Macon and threw the corpse in the lobby of the Douglass Theatre, near the scene of the crime. The police finally rescued it from the crowd of whites, both men and women, who thronged the place."

- New York Age, August 1, 1922.

"Hundreds of whites had converged on the area. Pushing and shoving, many shouted 'Burn him!' or 'Hang him up!' Others merely yelled 'Let's get a look at him!' Many of the revellers did, however, manage to kick and beat the corpse. Even a number of women were present, clamouring as eagerly as their male counterparts."

- Andrew Manis, Macon Black & White.

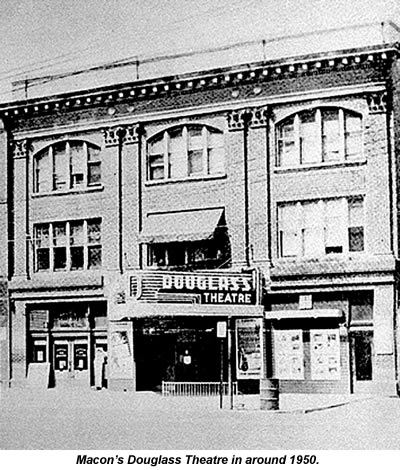

Waters returned to Macon's Douglass Theatre about two months after the Troubadours' June 1922 appearance there - this time for a gig of her own billed as "Ethel Waters of Black Swan Records" with just a single pianist to provide her music. The theatre, located between Mulberry and Cherry Streets on what's now Martin Luther King Boulevard, was owned by Charles Douglass, the son of a former slave who also owned a hotel and a barber shop nearby. This stretch of Broadway was Macon's most important Black neighbourhood, and the Douglass's role as a leading movie theatre and vaudeville playhouse made it a focal point for the city's whole African-American community. On her last visit Waters had found the streets around the Douglass jumping with all the vivacity of a miniature Harlem, but this time the atmosphere was very different. (1)

"We sensed something grim and forbidding about the place," she writes. "The people around the showhouse were the same as usual, except that they didn't say anything. It was as though a sorrow too profound to express hung over them. We weren't there long before we were told the truth. A colored boy had been accused of talking back to a white man. For that he'd been lynched, and the white mob that murdered the youngster had flung his body into the lobby of our theatre. They threw it there to make sure many Negroes would see it." (2)

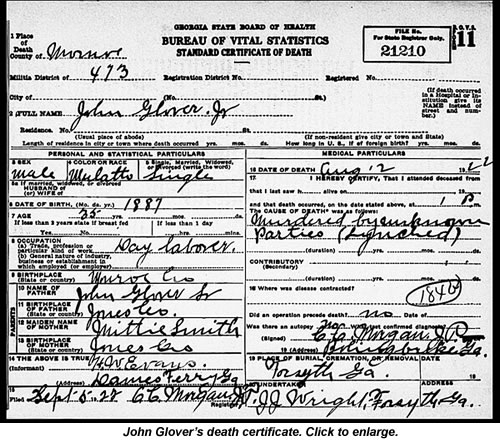

Waters tells us no more about the case than that, but a search of the newspaper archive reveals there's only one Macon incident she can have had in mind - and that's the vigilante murder of John "Cocky" Glover.

It was around 6:00pm on July 29,1922 - a Saturday night - when the Bibb County sheriff's office in Macon got a call saying there was a drunken young Black man waving a gun around and causing trouble at Hatfield's poolroom, right next to the Douglass Theatre. This man was Cocky Glover, a small-time crook and bootlegger who'd had run-ins with the local lawmen before. The sheriff sent three deputies called Walter Byrd, Romas Raley and Will Jakes out to see what was going on at Hatfield's and get it sorted out. (3)

Byrd, the leader of this little squad, was a big man, well over six feet tall, with a barrel chest and broad shoulders to match. He'd joined the sheriff's department about a year earlier, straight from his former job as a prison guard, and become something of a hero to Macon's white citizens for his role in investigating the Christmas 1921 murder of a white streetcar conductor called Lee Aligood, who'd died while defending his day's takings from thieves. The killers had also stolen his pistol, which Byrd later traced to a local pawn shop and used as evidence to arrest three Black men for the murder. These men were still locked in Macon's Bibb County jail awaiting trial when all the trouble at Hatfield's began. Here's the Atlanta Constitution's report to fill us in:

"The three deputies entered the poolroom, searched it and, failing to find Glover, started out [back into the street]. As they reached the doorway, they saw Glover on the sidewalk. The negro pulled a gun and began firing. Deputy Sheriff Byrd fell to the sidewalk in the poolroom doorway. The bullet struck him in the heart.

"Romas Raley pulled his gun as Glover fired his first shot, and returned fire. The negro ran, Raley said, into the poolroom, and the latter followed, shooting at him. The poolroom was crowded with negros making for the exits. Bullets from Raley's gun are believed to have wounded Marshall and Brooks [two of the fleeing customers]. Glover ran through the back of the poolroom with Raley following.

"The deputy lost the trail for a few minutes, but picked it up later. Other deputies were called in and joined the chase, which led to the river bank at Third Street. The negro eluded the deputies in some way and made his way to East Macon. Late tonight, deputies were looking for him there and were believed to be close behind him." (4, 5)

As this search began, ambulance workers were busy at Hatfield's, where Byrd died about 20 minutes after being shot. George Marshall and Sam Brooks, the two Hatfield's customers wounded in the gunfire, were taken to Macon's Black hospital, but neither was expected to survive long. "Marshall was shot while in the rear of the poolroom," says the Atlanta Constitution. "Sam Brooks was shot as he was eating ice cream at the soda fountain." Both men had managed to stagger out on to the sidewalk before collapsing near where Byrd himself lay. Two days later they were both dead, with Glover rather than Raley now being named as their killer. (6)

As soon as news of Byrd's death got out, gangs of white vigilantes began appearing on the streets around Hatfield's, leading police to lock down that entire block of Black-owned businesses. Shops, bars and cafes there were told they must close immediately, and paying guests were evicted from their hotel rooms and other lodging. "They drove all Blacks out into the streets, including guests at the Douglass Hotel," Andrew Manis writes in his 2004 book Macon Black and White. "Virtually the entire block was cleared out." (7)

I can see the sense of closing down the block's shops and entertainment venues to keep away its usual crowd of Saturday night partiers, but turning out the people who lived there into the very streets where they were now most at risk seems crazy. "Groups of men collected on the streets and occasionally took pot shots at negroes early in the night," the Atlanta Constitution story reports. "Two shots were fired at a negro in front of the Macon hotel and a shot was fired at another as he ran up Wall Street Alley. Another negro was fired at on Broadway, near Poplar. He hopped into an automobile and escaped."

Other papers add details of their own: a Black postman harassed three times by three different white gangs as he tried to work his evening route; Black delivery boys beaten up simply for the colour of their skin; white gangs forcing their way into Black families' homes under the pretext that they needed to search for Glover there. At the height of that evening's chaos, there were several hundred angry white men prowling the city's Black neighbourhoods, and it's only luck which prevented anyone being killed in their attacks. (8)

Rumours swirled round the city that the whole incident at Hatfield's had been deliberately orchestrated to lure Byrd there so that the waiting Glover could assassinate him. In this version of events, Glover was a hired hitman, paid by friends of the two men Byrd had arrested for the Aligood murder to extract revenge. He was just one small part of what some insisted was a "negro murder gang" threatening every cop in Macon. With each new retelling, this story ratchetted up white Macon's anger by another notch. Calmer, more rational thoughts were forgotten in an intoxicating flare of rage.

Charles Douglass was the richest Black man in Macon - perhaps the richest in the whole of Georgia - so it's no surprise that he found white resentment targeted at him too. Byrd's death just gave it a new focus, producing baseless accusations that he was hiding Glover in his Macon hotel. Police took the threats against Douglass seriously enough to place a guard of 20 men around his house and to give him a police escort through the evacuated block's white crowds that night to check his theatre's gas lights and heating boiler were safely shut down. Shouted allegations followed him all the way there and back, and persisted even when Deputy Chief Mullally spoke publicly in his support. "Nobody was responsible for that affair except a drunken menace," he said of Byrd's murder. "Douglass could not be connected with it any more than I could." (9)

Fears that the white thugs' behaviour would grow into a full-blown race riot were now very real - real enough for the Macon disturbances to make front-page news in papers as far away as New Mexico and Virginia. As Sunday morning approached and the streets cleared a little, those fears began to recede, leaving a sense of fragile calm to prevail as the sun came up and people prepared for church. The cops still guarding Hatfield's and its block of empty buildings had kept some sort of lid on things for now - but the Cocky Glover affair was far from over. (10)

Sunday remained peaceful, giving police a chance to get checkpoints in place on all the roads out of Macon and begin questioning the Black informants on their payroll. By close of play that day, they knew Glover had been hiding in the swamps on the edge of Macon and was planning to flee the city by train to Atlanta the next night. The problem now was how to arrest him and - more to the point - how to safely hold him for trial when Macon's white citizens were in such a turbulent mood. It would be only one short step from the trouble they'd seen on Saturday night to a lynch mob besieging the jail, and this time the numbers involved might be too big to control. "The Sheriff did not want Glover captured [in Macon], because it meant certain death to the negro," the New York Times later explained. (11)

Sunday remained peaceful, giving police a chance to get checkpoints in place on all the roads out of Macon and begin questioning the Black informants on their payroll. By close of play that day, they knew Glover had been hiding in the swamps on the edge of Macon and was planning to flee the city by train to Atlanta the next night. The problem now was how to arrest him and - more to the point - how to safely hold him for trial when Macon's white citizens were in such a turbulent mood. It would be only one short step from the trouble they'd seen on Saturday night to a lynch mob besieging the jail, and this time the numbers involved might be too big to control. "The Sheriff did not want Glover captured [in Macon], because it meant certain death to the negro," the New York Times later explained. (11)

It was decided Glover should be allowed to catch his train for Atlanta and arrested by the officers who'd be waiting for him there. That way, he could be held 80 miles away from Macon, in a city where the anger at Byrd's death was far less hotly felt. Private detective agencies like the Pinkertons then supplied what they called "spotters" to secretly travel up and down the line and report back to the rail companies' bosses about any ticket sellers they found pocketing fares. Three of these spotters - all of them Black - were recruited to join the scheme. Two would place themselves a few seats away from Glover on the train to keep eyes on him there, while the third waited at Atlanta's railway station with the white cops Mullally had already briefed. (12)

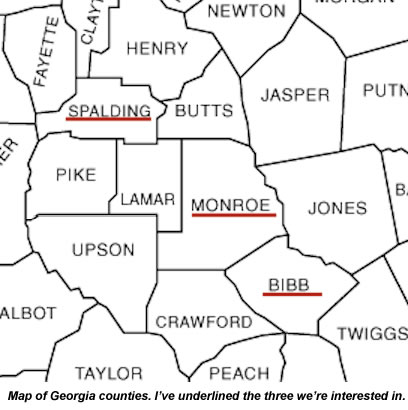

Glover boarded his Central of Georgia train in Macon late on Monday night, followed by the two spotters, and for a while it looked as though everything was going to plan. The line to Atlanta curved north-west from Macon's own Bibb County into Monroe County, then Lamar County, Spalding County and on. Stops were scheduled first in the Lamar County town of Barnesville, then in Spalding County at a town called Griffin. It was during this first leg of the journey that the train's conductor, a man named Beal, decided to put a spanner in the works.

Beal, who knew nothing about the plan to arrest Glover in Atlanta, recognized him as the man wanted for Byrd's murder. He wasn't silly enough to try and tackle a killer himself, but he did call ahead to Griffin, telling the station master there to have some local cops waiting to board the train and grab Glover while they had the chance. In fact, just one Griffin policeman seems to have turned up, an Officer Phelps, who approached Glover on the train when Beal pointed him out. Phelps knew nothing about the Atlanta plan either, so as far as he was concerned this was simply an escaping murderer.

"The negro was not taken without a struggle," the Atlanta Constitution reports. "When the officer approached him and asked what was in his pocket, he said 'Aw, that's nuthin' but a damn gun', then whipped out the weapon and began firing, shooting five times in all, one bullet striking Policeman Phelps in the hand. The officer, with the assistance of passengers on the train, finally subdued Glover and took him to the Spalding County jail where he was locked up." It was about 5:00am as the cell door clanged shut behind him, and Griffin's authorities were frantically wondering what to do next. What if the lynch mobs Macon's police had feared now converged on Griffin instead? There were even fewer police to guard the jailhouse there. (13)

After a hurried consultation between Griffin's Police Chief Stanley and its city manager, it was decided that Glover must be bundled into a car and driven straight back to Macon for the cops there to worry about. A later Bibb County Grand Jury investigation found this decision was motivated mostly by Stanley and his men's determination to collect the $400 bounty on Glover's head. "[They] thought it was necessary to deliver the prisoner to Bibb County to secure for the arresting officer certain rewards that had been offered," its report says. This was done "regardless of the safety of the prisoner, and having in mind only the collection of the reward." (14)

Glover was loaded into the car, accompanied by Chief Stanley, a patrolman called Huckabee and a local farmer named Roane, who I assume they invited along as a bit of extra muscle. They set off from Griffin at around 7:20 that morning, less than two-and-a-half hours after Glover had been captured there. Knowing that he'd almost certainly be tortured and lynched if he ever set foot in Bibb County again, Glover begged Stanley and Huckabee to give him a quick death right there in the car instead. "Kill me here," he pleaded as they sped south through the deserted country roads. "Don't take me back to Macon." But they wouldn't listen.

News of Glover's arrest reached Macon in record time, and a caravan of over 20 cars full of armed vigilantes quickly assembled there. By the time Stanley's car left Griffin, their own convoy was heading north along the same roads, determined to wrest Glover from police custody and kill him. More cars followed them as the news spread through Macon, increasing the convoy's total force to nearly 300 men. Now Stanley had another reason to keep his foot down: if Glover was going to be dragged away and lynched while they were still on the road, he could at least ensure that it didn't happen in Spalding County. Get him across the line into Lamar or Monroe, and at least the lynching itself would be some other police department's problem.

News of Glover's arrest reached Macon in record time, and a caravan of over 20 cars full of armed vigilantes quickly assembled there. By the time Stanley's car left Griffin, their own convoy was heading north along the same roads, determined to wrest Glover from police custody and kill him. More cars followed them as the news spread through Macon, increasing the convoy's total force to nearly 300 men. Now Stanley had another reason to keep his foot down: if Glover was going to be dragged away and lynched while they were still on the road, he could at least ensure that it didn't happen in Spalding County. Get him across the line into Lamar or Monroe, and at least the lynching itself would be some other police department's problem.

Stanley hadn't bothered to let the Bibb County sheriffs know he was bringing Glover back, but Mullally soon got wind of it anyway. He immediately called the Monroe County authorities, asking them to deploy their own officers on the road to stop Stanley's car as it passed through Monroe and force it to turn back. He reminded the Monroe sheriff just what was likely to happen to Glover if the Macon mob got hold of him, but all his requests were ignored. Mullally then sent out officers of his own, two to a car, telling them to cover all the roads leading into Macon in a bid to stop Stanley, take Glover into custody for themselves and remove him to some place of safely. It was one of these Bibb County cars, occupied by officers Newberry and Brannon, who spotted Stanley's car as it was passing through Monroe. Obeying Mullally's orders, though, seemed to be the last thing on their minds.

"Officers Newberry and Brannon, meeting the group of Spalding County officers with the prisoner, escorted them in the direction of Bibb County, passing through Bolingbroke," New York Age reports. "A mile from the latter point, they were overtaken by five men in a car [one of whom] was subsequently indicted for the lynching of Glover. No effort was made to arrest any of the five men in the car which had overtaken the officers, and it is stated that Officers Newberry and Brannon 'could hear, ahead of them, in the woods beyond, cars running in all directions'. Instead, the Bibb officers continued to guide the party on the main road toward Macon, directly into the mob that was scouring the country roads."

While all this was going on, Mullally was in his own car racing north. The first people he encountered were the bulk of the Macon caravan, some 250-300 people in all, who'd formed a roadblock near the Monroe County town of Forsyth. He seems to have spoken briefly to them before continuing north. A few minutes later, he found the cars carrying Stanley's party and his own two officers, but - according to the following month's Grand Jury report - made no attempt either to either stop them or to warn them to detour round the roadblock ahead. "Several roads were available by which this could have been done," New York Age tells us, "but evidence showed the prisoner was carried directly into the assembled mob." Mullally turned his own car south, just as Newberry and Brannon had, turning Glover's two-car convoy into three. (15)

As the three cars approached the Forsyth roadblock, someone ordered a path should be cleared for them and they were allowed to pass through. As they neared the Bibb County line, they were stopped again and everyone ordered to get out. Eight or ten of the mob's Macon ringleaders surrounded them now - about half of them armed - and Mullally recognized some of his own officers among the rest of the crowd: Will Mosely, Charlie Roberts, Lee Davis. He made one last plea for them to let him take Glover on to jail and a proper trial, but it did no good. The terrified prisoner was dragged a few yards away into the woods, followed by the mob's most bloodthirsty members. (16)

After a brief attempt to make him confess he'd murdered Byrd - which Glover refused to do - they tied him against a tree and emptied their guns into him. One paper speaks of "volley after volley", with "hundreds of bullets fired from shotguns, rifles and pistols". He must have been shot half to pieces, but for some that still wasn't enough. One group within the mob piled dry bush around Glover's feet and set fire to it, but others intervened to stamp it out. Finally, they cut his body down and threw it into a truck for the journey back to Macon. (17, 18)

The truck containing Glover's body got back to Macon at around noon and headed straight for Broadway, where Byrd had died on the sidewalk outside Hatfield's just three days earlier. All the other shops, bars and cafes along that block had been closed again by police order as soon as news of Glover's journey towards Macon came through, and all the Black people who'd normally have filled those businesses told to stay away. Everyone knew that if there was going to be renewed trouble in the city, this would be where it kicked off. Angry white crowds were already gathering there, listening for the sound of an approaching engine.

The truck containing Glover's body got back to Macon at around noon and headed straight for Broadway, where Byrd had died on the sidewalk outside Hatfield's just three days earlier. All the other shops, bars and cafes along that block had been closed again by police order as soon as news of Glover's journey towards Macon came through, and all the Black people who'd normally have filled those businesses told to stay away. Everyone knew that if there was going to be renewed trouble in the city, this would be where it kicked off. Angry white crowds were already gathering there, listening for the sound of an approaching engine.

The truck screeched into Broadway with its horn blasting, halted in front of Hatfield's, and someone on board dumped Glover's body out onto the sidewalk there. The crowd fell on it like a pack of starving animals, tearing away scraps of his clothes to take away as souvenirs or simply kicking and punching the corpse in a spasm of gratuitous hatred. One man climbed atop a Ford truck and started screaming "Let's burn him!" as four Macon policemen watched passively nearby. Any African Americans who wondered within sight were chased and beaten - as often by the cops as by the mob itself. Someone shattered the windows of Douglass's barbershop and began smashing up the furniture inside.

Finally, Glover's body was manhandled to a billboard outside the theatre and propped half-upright there. Some reports - such as Waters' - say it ended up in the theatre foyer, so perhaps the doors there had been broken open too. Macon city cops were dotted all round the area throughout these events, often only a few yards away from the worst abuses, but made no attempt to stop the riot. Finally, at long, long last, they moved in and took Glover's body to the safety of the police barracks. (19)

The Bibb County authorities were just as keen to avoid responsibility for Glover as those in Spalding County had been, so they quickly decided it should be Monroe County's job to deal with the body from here on. That was where Glover had died, after all. Later that day, his remains were delivered to Forsyth - though not with the quiet dignity one might have hoped. "The body was dumped in a lumber yard by an unknown group of men, who shouted 'Here's your nigger, you killed him'," August 2's New York Times reports. "Monroe County will investigate the case." (20)

Back in Macon, the crowds had drifted away from the Douglass Theatre to reconvene in nearby Central City Park. There were about 300 people there now, all stirring themselves into a frenzy and wondering where to vent that fury next. The plan they settled on was to march to Bibb County's jailhouse a few blocks away, overcome the guards there and lynch the three Black suspects being held for Aligood's murder. This idea was dropped when they saw the strength of the extra cordon of men Bibb County's Superior Court Judge Malcolm Jones had placed round the jail to ensure it was not invaded. After a little impotent shouting at the jailhouse walls, the mob broke up and returned home to swap war stories and take stock of their souvenirs. When Georgia's Governor Thomas Hardwick called Jones to ask if he needed state troopers to keep order from here on in, Jones replied he was confident his own men could handle it.

It seems to be a few days later that Waters arrived in Macon for her gig and found everyone around the Douglass in such a subdued mood. I can't explain why she doesn't mention the real accusations against Glover. Perhaps, when she came to write her book 30 years later, she simply confused him with one of the many, many young Black men who really were killed for something as trivial as talking back to a white man. In the end, it hardly matters: cop-killer or not, nothing could begin to justify the utterly barbaric way Glover's white neighbours chose to treat him, and Waters' account tells that larger and much more important truth well. "The house I was boarding at was next to the house of that dead boy's family," she writes. "I sat with them, prayed with them and tried to comfort them. But what is there to say to the mother of a lynched boy?"

Bibb County and Monroe County both launched Grand Jury investigations into Glover's death. Their job was to consider whether there was probable cause for criminal charges against any identifiable individuals involved in the lynching. If the answer was yes, those charges would go to trial as formal indictments, and it would be up to the trial jury to decide on each of the accused men's guilt or innocence. The Bibb County Grand Jury questioned nearly 200 witnesses and, on August 11, announced its first five indictments. The charges were rioting, assembling for the purpose of lynching and carrying a concealed or unlicenced weapon, and the five men named were:

Herbert Block (manager of the Hotel Dempsey).

Hector McSwain (President of Southern Co-operative Fire Insurance Co).

Nathan Unice (soft drink merchant).

Guy Jones (city fireman).

Gordon Herndon (auto mechanic). (21)

All five were arrested, but released again on bail ranging from $1,000 to $3,000 per man. On August 31, the Monroe County Grand Jury issued five indictments of its own in connection with Glover's lynching, this time on charges of murder. It was a very similar list:

Hector McSwain (President of Southern Co-operative Fire Insurance Co).

Nathan Unice (soft drink merchant).

Gordon Herndon (auto mechanic)

Troy Raines (grocer)

DL Wood (hotel clerk).

Once again, arrests were swiftly made and, this time, murder being a capital offence, no bail was allowed. The two Grand Juries both passed their evidence to prosecutor Emmett Owen and preparations for a trial began.

New York Age was pleased to see the process get this far, noting with satisfaction that even Block and McSwain, two of Macon's most prominent citizens, had not been able to escape it. But the paper had no illusions about why this particular lynching produced action when so many before it had not. "The reign of terror which swept the whole of Macon has aroused a number of white citizens to the fact that lynching is not merely an outrage against Negroes, but that it is a menace to orderly government and makes every citizen within its scope unsafe," the paper wrote. "If the men are tried, convicted and sentenced on the charges which have been brought, it will mark a new era in law enforcement in the state of Georgia."

There was another concern too. As all this played out in Macon, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill was going through Congress and had already been passed by the House of Representatives. If this Bill become law, lynching would be a federal crime rather than something that was left to the individual states to deal with. If Georgia's own politicians wanted to avoid that - and, believe me, they did - then they had every incentive to demonstrate they were perfectly capable of handling a matter like the Macon riots themselves. Hence their willingness to back the two Grand Jury enquiries and see the worst offenders brought to court. (22)

The murder trial was held in Forsyth in September, with Raines, Unice, Herndon and McSwain all in the dock. It was a farce, with many witnesses directly contradicting the Grand Jury evidence they'd given just a few weeks before. "One of the witnesses had told the Bibb Grand Jury he had seen Troy Raines participate in the Glover shooting," Manis points out. "Now, at trial in Monroe, he testified he did not recognize Raines." There were a lot of new-minted disagreements between the witnesses to deal with too. Manis again: "One witness had McSwain helping the officers to protect Glover, while another testified to seeing him place a rope round Glover's neck. One witness identified Raines as a member of the firing squad that shot Glover, while another claimed Raines was unarmed." Owen raised the possibility of perjury charges, saying he believed many of the state's witnesses had been intimidated. He'd never seen any case with so much changed evidence, he added.

The defence called no witnesses at all, opting instead to have each defendant give a lengthy speech on his own behalf. All four of them insisted they'd gone out to the lynching scene merely because they wanted to help the Bibb County officers battle the African American death gang they'd heard was targeting Macon's police. They were good family men, they said, who'd been in jail for 12 days and now wanted nothing more than to return home. It took the all-white jury just 30 minutes to acquit them all. (23, 24)

When the Bibb County Grand Jury's report was published a few weeks later, it revealed just how determined police witnesses had been to obstruct the initial investigation. Bibb County officers like Mosely, Roberts and Davis had spent 30 minutes mingling with men they knew well at the scene of Glover's death, and yet failed to identify a single one by name when questioned. "The evidence given by officers of the law was very meagre indeed, in spite of the fact that many of them have seen many years service in this county and knew most of the citizens in this county," the report complains. Macon's city police had proved equally unhelpful when asked to identify anyone involved in the Byrd or Glover riots, it says, adding: "This Grand Jury has had to rely almost entirely on evidence furnished to it by private citizens."

When Governor Hardwick had called him to offer state troopers to restore order in Macon, Judge Jones had declined, saying Macon's people were "law abiding citizens" who merely "got off the track" from time to time. The report took a very different view, pointing out that even those who'd not directly participated in the riots had encouraged bad behaviour by their determination to come along and gawp. This remark was picked up by a scorching editorial in New York Age:

"With sheriff's officers who willingly surrender their prisoner to the mob and look on at the lynching, a police force that permits the body to be thrown about in the street and aids the mob in assaulting inoffensive citizens because of their color, these 'good citizens' encouraged the proceedings to gratify a morbid curiosity.

"The findings of their own grand jury, while lacking in the specific testimony needed to convict individual members of the mob of murder, frame an indictment of the 'good citizens' of Macon, the brutish mob and the cowardly officials which should be embalmed in the court records to the eternal disgrace of the city."(25)

The only anti-lynching song anyone remembers today is Billie Holiday's Strange Fruit, recorded in 1939 from a poem published just two years earlier. What's forgotten is that Waters was performing an anti-lynching song of her own on Broadway as early as 1933 - and that it was memories of meeting Glover's parents which fueled her performance every night.

The only anti-lynching song anyone remembers today is Billie Holiday's Strange Fruit, recorded in 1939 from a poem published just two years earlier. What's forgotten is that Waters was performing an anti-lynching song of her own on Broadway as early as 1933 - and that it was memories of meeting Glover's parents which fueled her performance every night.

That song was Supper Time, written specifically for Waters by Irving Berlin as part of his 1933 Broadway revue As Thousands Cheer. It takes a slightly more oblique approach to its chilling subject than Strange Fruit does, but in its way it's just as powerful a song.

The concept behind As Thousands Cheer was to present 21 songs and sketches drawn from the news of the day, with each one given its context on stage by a backdrop collage of appropriate headlines. In the case of Supper Time, that meant a headline reading "Unknown Negro Lynched by Frenzied Mob", which appeared behind Waters as she walked on from the wings in a cheap housedress and pinny.

Her character for the song was a hard-pressed Black mother, still reeling from the news that her innocent husband has just been lynched. As she struggles to prepare her children's evening meal, she wonders how she's going to tell them that they'll never see their father again and - harder yet - how to preserve both their faith and her own in a merciful God. "How can I remind them to pray at their humble board?" Berlin has her ask. "How can I be thankful when they start to thank the Lord?"

"In singing that sing, I was telling my comfortable, well-fed, well-dressed listeners about my people," Waters wrote years later. "I had only to think of the family of that boy down in Macon, Georgia, to give adequate expression to the horror and defeat of Supper Time."

Sources and footnotes.

1) Many of this era's biggest blues stars appeared at the Douglass, including Ida Cox, Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. It was also an important venue for early Black cinema.

2) His Eye is on the Sparrow, by Ethel Waters (Da Capo Press, 1992)

3) It's not clear whether Glover's name was first mentioned in the initial call to the sheriff's office or only when sheriffs were briefing reporters about the evening's events. All the newspapers I've seen - Black as well as white - accept he was the man involved, though.

4) Atlanta Constitution, July 30, 1922.

5) Some other reports say a third Black man was injured by Raley's fire at Hatfield's, but he's never named and never mentioned again.

6) The change from Raley to Glover may have come as the result of fresh evidence emerging. It's equally possible, though, that the sheriff's department and the newspapers it briefed decided it would be more convenient to blame Glover for all three deaths and leave Raley out of it. He was one of their own, after all.

7) Macon Black and White, by Andrew Manis (Mercer University Press, 2004).

8) There were many more or less random arrests made among Macon's Black population that weekend too. Some were hauled in for daring to protest at being ejected from their hotel room, others simply because they'd had the bad luck to be in Hatfield's when Byrd was shot.

9) Mullally's boss, Sheriff Hicks, was out of town on the day Byrd died and would not return till August 8. That's why Mullally had to take charge of everything.

10) I've gathered reports of July 29's Macon trouble from newspapers in Mississippi, Kansas, Florida, Oklahoma, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, New Mexico and Florida - as well as Georgia itself, of course. They all put the story on page 1.

11) New York Times, August 2, 1922.

12) Railway carriages and all station facilities were segregated at this time, so a white spotter trying to follow Glover would have stuck out like a sore thumb.

13) Atlanta Constitution, August 2, 1922. Other reports add that one of the men helping Phelps had to club Glover unconscious before he'd give up the gun, and say the officer now faced the possibility of losing his arm.

14) New York Age ran lengthy excerpts from the Bibb County Grand Jury report in its October 7, 1922 issue.

15) It's hard to make sense of Mullally's actions here. All I can think is that he may have decided it was now too late to turn Stanley's car back and that his only remaining option was to get Glover to the relative safety of a Macon jail cell as quickly as possible.

16) Some newspapers reported next day that the car containing Glover had attempted to swerve round the Forsyth roadblock but immediately got stuck in the roadside mud. The implication is that it was only this bit of bad luck that allowed the mob to seize him. The subsequent Grand Jury report is clear that all three cars moved straight on through the roadblock, however, suggesting the mud story was made up by police to put their own actions in a better light.

17) The Grand Jury established that Mosely, Roberts and Davis were all among the men who watched Glover being shot to death but made no attempt to stop it. Two unnamed Griffin officers were watching too.

18) I'm struck by the anodyne language some white newspapers used to describe Glover's killing. The Charlotte News, for example, said simply that he'd been "put to death", leaving its readers to imagine a clinical, semi-judicial execution instead of the bestial cruelty that was really involved. Black newspapers were far franker in their own descriptions of lynching deaths.

19) I've compiled this account from the various press articles describing Macon's noonday riot. These include the New York Times (August 2, 1922), Durham Morning Herald (August 2, 1922) and New York Age (October 7, 1922).

20) Monroe County was none too happy about this, but went ahead and organised an inquest. The Forsyth coroner concluded Glover had been killed by persons unknown. The body was buried in the Black section of what's now Forsyth City Cemetery.

21) Bibb County issued lesser indictments against John Vann, Fred Whidden, Billy Smith and Alvin Hightower too. It also charged Macon police and the sheriff's departments of both Bibb and Monroe counties with neglecting their duty.

22) In the event, they needn't have worried. The Dyer Bill was killed in a Senate Filibuster by Southern Democrats in December 1922.

23) Atlanta Constitution, September 13, 1922.

24) I'm writing this in March 2021, which makes it impossible to miss parallels between the Macon rioters and the Trump supporters who invaded the US Capitol this year. The "negro death squad" rumours were Macon's equivalent of Q-Anon's idiocy, and there are other parallels too: the fact that the rioters included successful small business owners; the casual way they spoke of hanging another human being; their baffled outrage at being held to account.

25) New York Age, October 7, 1922.