Prototype Peaky Blinder stabs a Birmingham policeman to death during a March 1875 riot. Four months later, he's hanged for murder at Warwick Gaol.

Prototype Peaky Blinder stabs a Birmingham policeman to death during a March 1875 riot. Four months later, he's hanged for murder at Warwick Gaol.

The Broadside

This A4 ballad sheet, kindly supplied by West Midlands Police Museum, was produced by Thomas Sansom's Birmingham print shop, which gave it the full title Corkery's Farewell to his Mother, Brother and Sisters. The lyrics themselves are credited to "J. West", whose efforts I've tidied up a little in my transcript below. I've also left out the ballad's preamble verse so we can get straight into the story.

It's unusual to find a gallows ballad sheet like Corkery's printed as late as 1875, because by then public hangings had already been replaced by ones in the privacy of a prison yard. This deprived ballad sellers of one of their major marketplaces for verses like these, which could previously have been expected to sell briskly among the watching crowd. The fact that Sansom thought it was worth producing a ballad sheet about Corkery at all tells us the case must have generated a lot of public interest.

The Ballad

CHORUS

Oh my poor mother dear, for your son just shed a tear,

And think of me when I am far away,

My brother, sisters too, I hope will be kind to you,

Till we all meet on that Great Judgement Day,

He lay in Warwick Gaol, his fate he did bewail,

His companions now in sorrow do complain,

They think of friends so dear, who are shedding many tears,

And whose sentences have caused a deal of pain,

The sentence it was passed, poor Corkery's die was cast,

On the scaffold, oh 'twas such an awful fate,

Alas! He is no more, his friends they suffer sore,

Take warning, all, before it is too late,

His companions now, you see, have escaped the fatal tree,

Their sentences were most severe to all,

'Tis done without a thought, the evil doer's wrought,

And by Satan's dark temptation now they fall,

Oh, you parents only think, what it is to be in drink,

What crimes and depredations follow then,

You are good for any strife, to use poker or use knife,

And to act like beasts instead of being men,

Foul Satan and his imps attend everyone who drinks,

But moderation is a maxim true,

For men forsake their home, and women too will roam,

And for wicked crimes then, some are made to rue,

Poor Cresswell and Charles Mee, Thomas Leonard, now you see,

And Thomas Whalin they have sent for life,

Four men in youth and bloom, perhaps to meet their doom,

Pray think upon it, and avoid such strife,

We hope with Heavenly love, to see Corkery up above,

With angels, and his soul forever blessed,

For your dearest parents' sake, all your crimes you must forsake,

Then their happiness and minds will be at rest.

The Facts

The term "Peaky Blinders" was still a decade away from being coined when Jeremiah Corkery and his mates ran riot in the streets of Birmingham - but that's what they were in all but name. The city's slum areas then had nowhere near enough police to keep its violent street gangs under control, nor to stem the tide of public brawling, petty crime and sometimes serious assaults these gangs inflicted on their neighbours. Any policeman daring to interfere in this mayhem was liable to find himself rapidly outnumbered and beaten to the ground. Corkery's victim, PC William Lines, was the first Birmingham policeman the gangs actually killed, but would not be the last. (1, 2)

Attacking the local coppers was a regular sport for men like these, who knew their own superiority of numbers meant they'd almost certainly get away with it. "Some parts of the town on Sundays are monopolised by roughs, who amuse themselves with gambling, throwing brickends at houses, assaulting peaceably disposed foot passengers and rescuing prisoners from the custody of the police," the Birmingham Daily Post complained in June 1873. "Consequently those parts of the town are actually given up to mob law." The area around Garrison Lane was described by one factory owner there as "a veritable pandemonium [where] the peaky blinder and the rough reined supreme". (3, 4)

It's worth saying right away that - unlike TV's stylish Shelby family - the real Peaky Blinders were not remotely worthy of being romanticised or admired. The social historian Carl Chinn, who's written several books on Birmingham's gang history, is great grandson to a genuine Peaky called Edward Derrick, and entirely clear-eyed about the damage such men inflicted on everyone around them. "As a wife-beater, thief, wastrel and violent ruffian, [Derrick] was typical of the peaky blinders," Chinn writes. "They were not fashionably dressed, they did not have a certain charm, they did not have a certain sense of honour and they were not respected by Birmingham's working class. [.] Most importantly, they were not glamorous. They were brutal and vile." (5)

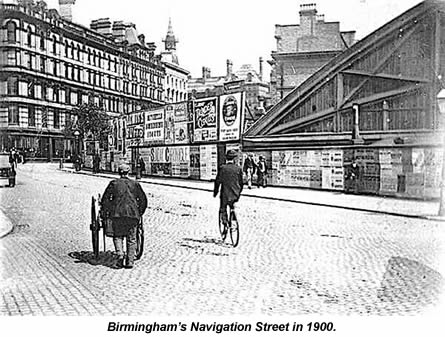

For proof of that, we need look no further than Birmingham's Navigation Street Riot on Sunday, March 7, 1875. The trouble began between 8:00 and 9:00 o'clock that evening, when George Cunnington, the landlord of a Fordrough Street pub called the Bull's Head, summoned two plain clothes officers there to deal with a recent robbery. On the previous evening, one of his staff, a young woman named Sarah Hyde, had heard signs of a commotion in Mrs Cunnington's room above the bar and peeked through the keyhole to see William Downes and another man searching the room. She reported this to her boss, who shortly afterwards discovered some of his wife's property was missing.

Downes was drinking in the Bull's Head on the Sunday night when Cunnington brought Detective Constables Fletcher and Goodman there to arrest him. Corkery was in the pub that night too, along with ten of the eleven other young men who'd later be arrested for the riot that followed: William Kelly, John Cresswell, Richard Smith, Thomas Whalin, Aaron Rogers, Samuel McNally, Stephen Gannott, Thomas Jackson, Thomas Leonard and Thomas Boden. The oldest members of this group were 23, and the youngest just 17. At least four already had criminal convictions on their record.

Fletcher and Goodman cleared the pub of all but a handful of its jeering customers, most of whom hung around outside to see what would happen next, then arrested Downes and marched him off towards the nearest police station. That's when Corkery emerged from the other bar and realised what had happened. "Corkery cried out, 'Have they got Bill Downes? Come on!'" the pub's housekeeper later testified. "He then rushed out of the house, and Smith and Cresswell went out after him." Whalin, who'd been warming his behind against the pub's fire, followed a few seconds later. (6)

Cunnington added that the two detectives and their prisoner were no more than four or five yards from the pub when Corkery burst out and led a mob of some 15-20 men in the chase after them. "They all went towards Navigation Street," he testified. DC Charles Fletcher confirmed this. "We had not proceeded far before someone yelled out, 'They are taking Billy, let's give it to the bastards!'," he said. "We were then followed and stoned. When we reached the corner of Fordrough Street we met PC Lines, to whom I cried to keep back the mob. I then hurried with my prisoner to the lock-up, on the way meeting Sergeant Joseph Fletcher near the corner of Navigation Street and Suffolk Street. I cried out 'For God's sake, run back and assist Lines'." (7)

Sergeant Fletcher did so, getting there just as Lines was chasing one of the pursuing mob away. Fletcher himself was immediately attacked and knocked to the ground by Chesswell with a jagged wound over his left eye. Chesswell, Corkery and Whalin then fell on Fletcher, kicking him in the head till he lost consciousness. Seeing his fellow officer down, Lines ran over to rescue him, striking Cresswell on the head with his police-issue staff as he did so. Corkery and Whalin fled too, but Corkery did not run far.

"[Corkery] looked back," Thomas Leonard later claimed. "I saw him put his hand in his pocket, pull out a knife and run down the street his hardest. I saw him get up to the constable. He then ran back again and, coming down the street by me, said, 'It's me that has chivied him. See? Feel the knife, it's wet'." In the street slang of the time, to "chivy" someone meant to attack them with a knife. (8, 9)

James Moore, a Fordrough Street umbrella maker, saw the attack too. "Corkery came up and ran at Lines," he testified in court. "I saw him raise his hands and strike the constable two blows upon the side of his head. Just as Corkery ran at him, Lines' staff struck him on the eye. The officer then staggered and fell." Later in his testimony Moore added, "I saw Corkery run up to him. I saw the blade of the knife which he held in his hand and saw him put it up to Lines' face and run away. Lines began to bleed from the left ear." (10)

Other witnesses gave very similar accounts. "Corkery stabbed Lines in the ear at the same time Lines struck him with his staff," said local resident Walter Vernon. "Corkery then ran up Navigation Street, up Fordrough Street, and Lines staggered against the lamp-post. I saw blood running down from his ear." Thomas Whalin's sister Ann testified that Corkery had struck Lines with something on the side of the ear. "Blood flowed immediately from the side of his head," she said of the moment Lines collapsed.

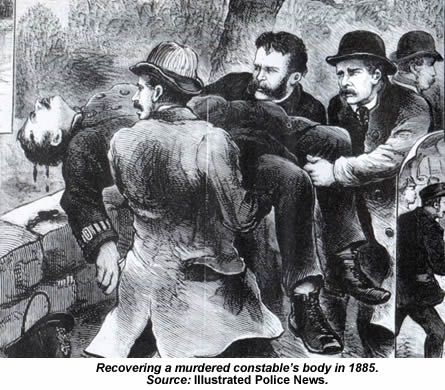

A couple of kindly passers-by - a woman and her young son - had helped Fletcher to his feet by now and were leading him towards a nearby cabbie who'd volunteered to take him to hospital. As he staggered past Lines on the ground, Fletcher heard him say, "I'm dying".

John Cruise, a decorator lodging at the Bull's Head, described the night's events too. "Leonard, Jackson and another man named Mee came into Fordrough Street with a policeman's helmet, which they threw down in the road and jumped on," he testified. "[Mee] said, 'We have done him'. They then turned away, but immediately a number of them came running up from the direction of Navigation Street. Corkery was leading them, and he cried out that the coppers were coming."

Cruise ran into Corkery again next day, seeing he now had a bandage over his right eye where Lines' staff had hit him. "I said to him, 'You've got it hot'," Cruise told the court. "He replied, 'Ah, I got knocked down, but the copper is stabbed'. He later said, 'I done it; I chivied the copper'. He also said that, if Whalin or Rogers were pinched for stabbing, he should round that it was him." This time, the slang term used meant "confess". (11)

Lines was taken to Queens Hospital, where he was found to have a severe wound under his left ear which was still bleeding. Speaking from his hospital bed, he said Whalin, Rogers, Cresswell and one other man he did not recognize had all been near him when he was stabbed. "It must have been one of the four that stabbed me," he added. "But I could not say which." Lines survived for 17 days after the riot, but died in hospital on March 24. Queens' house surgeon Francis Hamilton confirmed it was the stab wound that killed him. (12, 13)

Arrests of the rioters began almost immediately, with Cresswell and Rogers taken into custody on March 7 and Smith and Whalin the next day. Corkery himself was arrested on March 10. The magistrates' hearing to determine who should ultimately face which charges was held on March 30 at Birmingham Police Court. Corkery, Kelly, Cresswell, Smith, Whalin, Rogers, McNally, Gannott, Jackson, Leonard and Boden were all in the dock there, plus another young man called Dennis Kennedy who seems to have joined the riot part way through. Charles "Barber" Mee, the man Cruise would later say he saw stamping on a policemen's helmet, had not yet been implicated in the riot, and so escaped this first hearing.

Of the 12 men before the magistrates that day, Kennedy, Smith, Jackson, Gannott and Boden were discharged for lack of evidence. Told they were free to go, they charged straight out of the court into a gathering of their waiting friends and families. "Quite a scene took place, a large crowd immediately surrounding them," the Post reported. "The whole then adjourned to a neighbouring public house."

The remaining seven men were all formally charged with taking part in a riot and assaulting the police. "All of them looked very serious and two of them cried," said the Post. Corkery was then further charged with the deliberate murder of PC Lines. His fate would be decided at Warwick Assizes on July 9. (14)

Lines was buried at Birmingham's Witton cemetery on March 29, 1875. Pavements and windows all along the route of his funeral procession were packed with mourners, the men solemnly removing their hats as the coffin passed by and many of the women in tears. "All Aston appeared to have turned out for the occasion, and the vast space of wasteland near the brook was literally covered with human beings," next day's Birmingham Mail reported. "The branches of trees and dead walls furnished accommodation for those who desired to be spectators of the scene. There could not have been less than 100,000 persons throughout the entire route."

Lines was buried at Birmingham's Witton cemetery on March 29, 1875. Pavements and windows all along the route of his funeral procession were packed with mourners, the men solemnly removing their hats as the coffin passed by and many of the women in tears. "All Aston appeared to have turned out for the occasion, and the vast space of wasteland near the brook was literally covered with human beings," next day's Birmingham Mail reported. "The branches of trees and dead walls furnished accommodation for those who desired to be spectators of the scene. There could not have been less than 100,000 persons throughout the entire route."

As the city waited for Corkery's murder trial to begin, his friends were busy trying to intimidate the witnesses expected to testify against him. Ann Whalin, Thomas Whalin's sister, who'd named Corkery as Lines' killer at the earlier hearing, was one of those targeted. Her attackers claimed that she and other witnesses in the Police Court had agreed to pin the murder on Corkery to ensure their own friends and family would not hang for it instead.

One Saturday night in late March, Ann and three female friends (one of them called Margaret Morgan) were attacked in Wharf Street by a couple who lived there. "James Hamilton and his wife threatened and menaced them, accusing them of swearing away the lives of innocent men," the Birmingham Mail told its readers. "The men then struck and kicked Whalin and chased Morgan from the corner of Wharf Street to Navigation Street." Ann protested to police that she'd been left in fear of her life, and the Hamiltons were duly arrested. (15)

In a separate incident the same day, a man called John Shannon was rash enough to criticise Corkery and the other indicted rioters while drinking in a Navigation Street pub. This earned him a beating from two of the pub's other customers and a trip to Queens Hospital to have his forehead wounds taken care of. Once again, the attackers were arrested.

Corkery's murder trial on July 9 called all the same witnesses we've heard from already, who repeated the accounts they'd given in the Police Court four months earlier. In his closing statement for the defence, Corkery's lawyer did what he could to cast doubt on this evidence, saying several of the witnesses were friends of Thomas Whalin's who "clearly had a motive and an interest in coming here to save one at the expense of another". This was the same accusation Ann Whalin's attackers had flung at her in Wharf Street, and was repeated later in court by Corkery himself. "There is a plot to put me in this case and to get other people out," he told the jury as his trial neared its end. (16)

All the swagger and cheek Corkery had shown at the previous hearing had now vanished. "Throughout the whole of the case, there was an absence of that defiant carriage which characterised him before the magistrates," the Post remarked. It took the jury just 15 minutes to find him guilty of murder, at which point the judge donned his black cap and sentenced Corkery to hang. As the sentence reached its customary final words - "May the Lord have mercy on your soul" - Corkery uttered a faltering "Amen".

While awaiting his execution, he wrote to Home Secretary Richard Cross, confessing now that he had killed Lines but begging to be spared the death penalty. Cross replied that the law must take its course. Corkery's friends and family got up a petition making the same plea, and presented that to the Home Secretary too, but got the same chilly response. (17)

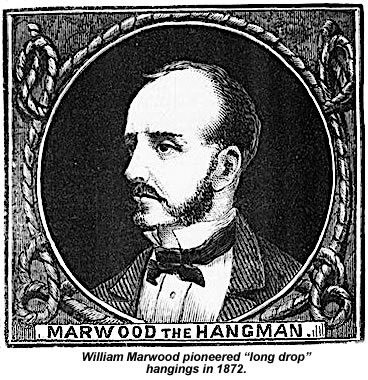

The hanging itself followed on Tuesday July 27 at Warwick Gaol. Preparations had begun the day before, when the Lincolnshire-born hangman William Marwood arrived to check the prison's gallows was in good order. Unlike the raised platform we're used to seeing, Warwick's mechanism placed its trap door at ground level, the prisoner dropping into a deep brick-lined pit beneath when the trap was pulled. The noose was attached, via a short length of iron chain, to a sturdy horizontal bar above, fixed to the walls on either end at the yard's narrowest point. Marwood, who'd pioneered the "long drop" technique of hanging a man three years earlier, seemed to distrust the chain used at Warwick, looping his rope back on itself to tie it directly to the supporting beam as well. (18, 19)

Corkery spent a disturbed night. "On Monday night he retired to bed about eleven o'clock, " the Post reported on July 28. "He, however, got very little sleep, tossing about in a troubled manner, and evincing much mental suffering. He rose at 4:30, and from that time until the moment of his execution his terror and consequent helplessness appeared to rapidly increase. Breakfast was offered him, but he refused to touch it, and sat in his cell in a most wretched and dejected state."

At about 7:00am, an hour before the hanging's scheduled time, a priest named Kelly visited Corkery in his cell where they prayed together for a while. At a few minutes to eight, he was led, along with Father Kelly, to a small room where Marwood introduced himself and supervised the process of Corkery's wrists being tied together. "[The prisoner] made no remark, paying undivided attention to the priest," the Post tell us. "Scarcely had the operation been concluded when the clock of St Mary's Church, Warwick, began to strike the hour of eight. The party then proceeded to the gallows." (20)

Waiting for them there was a small crowd of prison officials and reporters, including the Post's man, who filed this eye-witness report:

"The morning was beautifully fine, there being a clear blue sky overhead and the sun shining brightly. The very beauty of the morning, however, appeared by contrast to intensify the deathly and shocking look of the condemned man. He walked slowly and hesitatingly forward, stopping when about four feet from the gallows, and appearing as though about to faint. His face was deadly pale, his mouth half-opened and his eyes nearly closed. He trembled violently and his knees occasionally seemed to almost give way.

"Marwood took him by the shoulder and gently urged him forward onto the drop, placing him immediately below the fatal noose. A short halt was then made, and Father Kelly, advancing to the front of the culprit, took him by the hand and motioned to him to kneel. Corkery immediately did so, dropping heavily on his knees, and causing the drop to give forth a hollow sound. Father Kelly then knelt in front of him, and commenced a long, confessional prayer, Corkery repeating the words.

"During this prayer, the priest held close to the condemned man's face a black ebony crucifix, occasionally waving it gently before his eyes. Corkery expressed his deep sorrow that he had been guilty of a fearful offence, and humbly implored mercy. At one point there occurred a sentence referring to the death he was about to meet, and on repeating those words, the murderer's head sank to his breast.

"At the conclusion of these devotions, Corkery was told to rise. All his strength, however, seemed to have deserted him. He made an effort to regain his footing, but would have been unsuccessful had not two of the wardens assisted him. On being placed in an erect position, he staggered and would have fallen had not the wardens again been vigilant. Marwood, however, steadied the culprit, and from that time he stood pretty firmly.

"While his legs were being pinioned, he repeated another prayer with father Kelly, and continued to do so until the executioner drew the white cap over his face. At this time, the felon's features were dreadfully agitated, his lips working convulsively, and there being strong nervous twitches of the muscles of the face.

"Probably in consequence of Corkery placing his chin on his breast, Marwood was some considerable time in adjusting the rope. At length, however, he accomplished it to his satisfaction, and stepping quickly across the drop, he ran half-way down the stairs leading into the pit, and drew aside a long iron lever. In a moment, the drop fell with a dull, heavy sound, and the unhappy murderer's body descended a distance of nearly five feet with a swift rush, being 'brought up' at the end of the rope with a terrific jerk." (21)

In all probability, Corkery died instantly of a broken neck - that was the whole point of Marwood's long drop method after all. The observers gathered round the drop noted some convulsive movement in his body as it twisted slowly back and forth on the rope, but this was ascribed to post-mortem muscular contractions. Marwood reached out a hand to still the body's spin as Father Kelly continued his prayers.

Wardens hoisted a black flag over the gaol's main gates, telling the crowd of some 15 people gathered there that Corkery was dead. After the customary hour left hanging on the gallows, his body was taken down, placed in a cheap coffin, and interred with other murderers in the prison's own graveyard. "Thus passed away Jeremiah Corkery, who was guilty of a fearful crime, and who amply merited its terrible punishment," concluded the Post. (22)

Notes

I know of two other Peaky Blinders ballads besides this one. The first, entitled, Condemnation of Jeremiah Corkery, seems to think that Cresswell, Leonard, Mee and Whalin ended up in Australia:

The Judge in solemn terms addressed them,

"You are found guilty, every one,

And for life I now transport you,

For the law it must be done."

In fact, England had stopped sending convicts to its overseas penal colonies in 1868, seven years before the Navigation Street Riot took place. My guess is that whoever wrote this ballad had adapted it from an earlier set of verses, and carelessly failed to update their transportation reference as he slotted in the new names.

Our third and final Peaky Blinders ballad was found by song collectors interviewing a Birmingham woman named Cecilia Costello in 1967. Costello, born in 1884, had seen plenty of Peakies in her own neighbourhood as a teenager and still recalled the pride local girls took in dating them. Questioned by folk music researchers Charles Parker and Pam Bishop, she sang them this old street song from the 1890s:

My bloke's a Peaky, none the worse for that,

He's got bell-bottom trousers and a Peaky Blinder's hat,

Rings on his fingers and round his neck a daff,

So all you nosey parkers can take it out of that. (23, 24)

A Mrs Holden from Halesowen in Dudley contributed an additional verse of this song, presumably one she remembered from her own youth, which has since found its way into the English Folk Dance & Song Society's collection:

Never trust a Peaky an inch above your knee,

I've trusted one, and he's been the ruin of me,

He went away and left me with a baby on my knee,

My chap's a Peaky, Peaky Blinder.(25)

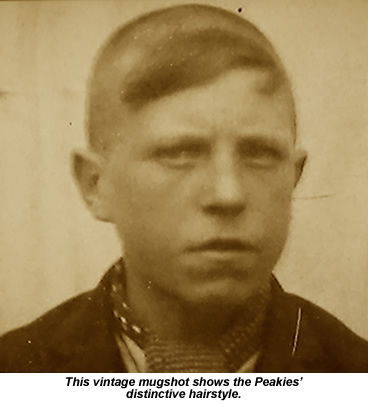

Costello's memory of the Peakies' wardrobe is confirmed by many other sources. Arthur Matthison's 1937 memoir, Less Paint More Vanity, for example, recalls the typical Peaky he'd met in Edgebaston as a young man. "He took pride in his appearance and dressed the part with skill," Matthison writes. "Bell-bottomed trousers secured by a buckle belt, hob-nailed boots, a jacket of sorts, a gaudy scarf and a Billycock hat with a long elongated brim. His hair was prison cropped all over, except for a quiff in front, which was grown long and plastered down obliquely on his forehead."

The hats Matthison describes were modified bowlers, with their front brims reshaped to form a peak like the spout of a jug. This part of the brim was pulled down sharply over the wearer's right eye, partly blocking his vision. The popular name for a hat like this - a peaky blinder - came to describe the men who wore them too. The real Peakies were a loose collection of small street gangs rather than the single, organized force the Shelbys run on TV, and by 1895 the name was being applied to any of the city's unruly young men. Newspapers used the phrase "peaky blinder type" in the same vague way they'd label someone a "hooligan" today. (26, 27)

Around the turn of the century, Billycock hats gave way to flat caps, but the notion that the Peakies sewed razor blades into these caps was never more than an urban myth. Chinn traces its wider spread first to a 1950s campaigner called Norman Tiptaft, who used the claim to promote his own alarmist views on Birmingham crime, and then to John Douglas's 1977 novel, A Walk Down Summer Lane. He's very clear that the notion is completely untrue. "There is no evidence they sewed razor blades into the peaks of their caps," Chinn writes. "Of all the weapons noted in police, court or newspaper reports of attacks by peaky blinders, none mention the use of a razor blade sewn into the peak of a flat cap. Likewise, no such weapon is recalled in the memories of people from the time." (28)

The Peaky's real weapon of choice was his belt, quickly whipped from the waist and wrapped tightly round his fist with the heavy buckle swinging free to act as a flail. Almost every report of trouble involving the Peakies in the 30-year period I've looked at mentions these belts and the vicious injuries they could inflict. George Eastwood, whose 1890 beating I mention in the footnotes below, was just one example. "He was overcome by a terrible blow from a buckled belt [.] and was struck several times about the head with buckled belts," The Birmingham Daily Mail reported. Eastwood was left with a fractured skull and wounds to his scalp up to an inch long.

And finally .

Of all the clippings I unearthed while researching the real Peaky Blinders, this may be my favourite. It's taken from the Birmingham Daily Mail of May 30, 1896:

A big PlanetSlade thank you Corinne Brazier of West Midlands Police Museum for her help finding the original ballad sheets and Corkery's mugshot. Thanks also to the EFDSS library for its information on My Bloke's A Peaky.

Sources & footnotes

1) The first printed reference we have to "peaky blinders" appears in the Birmingham Daily Mail of March 24, 1890. This reported a "murderous outrage at Small Heath", where an innocent man had his skull fractured by "several men known as the 'peaky blinders' gang". George Eastwood, singled out by the gang simply because he'd ordered a non-alcoholic drink in an Adderley Street pub, was so badly beaten that he had to be trepanned.

2) Even a cursory study of the newspaper archive reveals a string of attacks on Birmingham police at around this time, with knives or thrown bricks and bottles the weapons most often used. Officers named Snipe and Gunter were murdered by Birmingham gangs in 1897 and 1901 respectively. "We fear there will be more constable-slaughter in Birmingham," said the city's Daily Gazette.

3) Birmingham Daily Mail, June 23, 1873.

4) Birmingham Daily Mail, July 10, 1901.

5) Peaky Blinders: The Real Story, by Carl Chinn (John Blake Publishing, 2019). Chinn also appears in a two-part BBC television documentary called The Real Peaky Blinders, which will remain available on iPlayer till March 2023.

6) Birmingham Daily Post, March 31, 1875.

7) Fordrough Street has long since vanished beneath the developers' bulldozers. It stood roughly where the western end of Navigation Street meets the Queensway traffic system today.

8) There were gasps of horror from the crowded public gallery as Leonard gave this testimony.

9) This usage survives in our term "shiv" for an improvised prison blade.

10) The second part of Moore's account here came at Corkery's murder trial, which was reported in the Birmingham Daily Post of July 10, 1875.

11) Cassell's Dictionary of Slang, edited by Jonathan Green (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998).

12) Corkery, unlike the other three men Lines names here, did not live on the officer's own beat. Assuming the fourth man was Corkery, that may explain why Lines didn't recognise him.

13) Lines was just 30 when he died, and left behind a wife and young daughter. He'd been in the police for 11 years.

14) Cresswell, Leonard, Mee and Whalin were later given life sentences with hard labour for their actions in the riot. The rest received sentences of up to 15 years. Downes and a man called Carey - his partner in the original robbery - were sentenced to five and 15 years respectively.

15) Birmingham Mail, March 30, 1875.

16) This idea that Corkery was innocent may explain why the ballad takes a relatively sympathetic view of him ("Poor Corkery" etc).

17) Corkery would confess to Lines' murder twice more before he died: once to relatives visiting him in his cell and once to Warwick Gaol's Governor Anderson.

18) Any mishap on the day could have resulted in Corkery being given a long, choking death rather the instant demise from a broken neck Marwood's long drop method was designed to ensure.

19) Marwood hanged a total of 176 people in his nine years as an executioner. He was famous enough for a jokey little street rhyme to appear about him: "If Pa killed Ma / Who'd kill Pa? / Marwood."

20) I can never think of the moment Marwood introduced himself to Corkery without remembering a line from Elvis Costello's Let Him Dangle: "As the hangman shook Bentley`s hand to calculate his weight".

21) Birmingham Daily Post, July 28, 1875.

22) According to the Post, most of the people gathered outside the gaol were "women and young girls, some of the latter having infants in their arms". They seem to be hinting that the girls in question were Corkery's baby-mamas.

23) You can hear Costello's preamble and her own performance of the song online here. The Birmingham folk singer Jon Wilks uses her verse with a different tune in his 2018 recording of Aye For Saturday Night.

24) "Daff" had me puzzled here till Wilks explained it was the slang word for a silk scarf. That's supported by Holden's version of the song, which gives the line as "a muffler round his neck".

25) This verse takes us back to the young mothers gathered outside Warwick Gaol as Corkery swang.

26) A June 17, 1899, letter in Birmingham's Sports Argus complains about encountering aggressive cyclists "of a very peaky blinder type" on Jockey Hill in Sutton. The writer also calls them "cads on castors".

27) A July 1901 story in the Nuneaton Tribune gives a glimpse of the hold Peaky Blinders had on the public imagination. A mentally disturbed man found begging in Nuneaton's Coventry Street told police there that the Peaky Blinders wanted to kill him. Once it would have been ghosts or evil spirits troubled souls like him lived in fear of, but now it was the Peakies.

28) I don't mean to criticize Steven Knight, the TV show's creator, at all here. I'm a massive fan of the epic he created - it's arguably the best telly of the past 10 years - and I think he was entirely right to "print the legend" in how he chose to tell it.