Street ballads would be produced just as quickly as the newspapers they competed against, often appearing on the streets just a few hours after the trial or execution they described, and offered London's poor a far more affordable way to keep up with the most entertaining aspects of the news. At a time when newspapers cost sevenpence or more, ballads could be had for just a penny, and that made them a very big part of the literate poor's reading.

Street ballads would be produced just as quickly as the newspapers they competed against, often appearing on the streets just a few hours after the trial or execution they described, and offered London's poor a far more affordable way to keep up with the most entertaining aspects of the news. At a time when newspapers cost sevenpence or more, ballads could be had for just a penny, and that made them a very big part of the literate poor's reading.

“One paper-worker told me that, in some small and obscure villages in Norfolk, it was not uncommon for two poor families to club for 1d to purchase an execution broadsheet,” Mayhew writes. “Not long after Rush was hung, he saw one evening, after dark, through the uncurtained cottage window, eleven persons, young and old, gathered round a scanty fire. An old man was reading, to an attentive audience, a broadsheet of Rush's execution, which my informant had sold to him.”

That Rush broadsheet was phenomenally popular, as Mayhew discovered when he asked his contacts in the trade to calculate some sales figures. This produced the following table of six recent executions:

| James Rush (1849) | 2.5m copies |

| Frederick and Maria Manning (1849) | 2.5m copies |

| Francois Courvoiser (1840) | 1.66m copies |

| James Greenacre (1837) | 1.66m copies |

| Daniel Good (1842) | 1.65m copies |

| William Corder (1828) | 1.65m copies |

By far the oldest of the cases in Mayhew's table is William Corder's execution for the 1827 murder of Maria Marten near Ipswich. The song that story inspired - Murder in the Red Barn - began its life as a set of verses on Jemmy Catnach's broadsheet, and is still regularly recorded today. By the time Mayhew gathered his data no-one could put a firm figure on how many copies Thurtell's even older tale had shifted, but all agreed its total sale had been “enormous”.

“The money expended for such things amounts to upwards of £48,500 in the case of the six murders above given.” Mayhew writes. “All this number was got up and printed in London.” On that basis, London sales for the six most popular ballads would have totalled about £4.9m in today's money. Rush alone would have brought in over £1m for the balladeers, and went on to provide a healthy income for other story-tellers too.

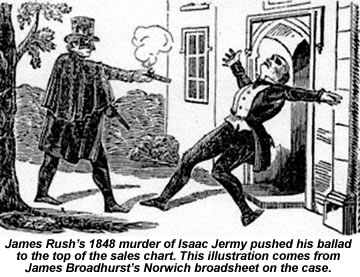

James Rush was a tenant farmer in Norwich, who owed his landlord, Isaac Jermy, the huge sum of £5,000. As the deadline for payment approached in November 1848, Rush shot Jermy and his son Isaac Jr dead on the porch of their Stanfield Hall home. He also shot Jermy Jr's pregnant wife and Eliza Chestney, her serving maid, but both of them survived.

Jermy was embroiled in a dispute about ownership of the estate, and Rush hoped the rival claimants would be blamed for his murder. He wore a wig and false whiskers - some say a mask - to disguise himself as he shot the family. Unfortunately, Rush's girlfriend Emily Sandford, who he'd been relying on to support his alibi, declined to co-operate in court and, despite his vigorous efforts to defend himself, Rush was hanged at Norwich Castle.

Mayhew was impressed by the quality of the Rush broadsheet he inspected. “Rush's sorrowful lamentation is the best, in all respects of any execution broadsheet I have seen,” he writes. “Even the copy of verses [...] seems, in a literary point of view, of a superior strain to the run of such things.” Mayhew also points out that these verses are always supposed to have been composed by the condemned man - adding wryly that even illiterate criminals seem able to accomplish this - and notes the unusually sympathetic tone these take in Rush's case.

You can see what he means. Most killers given a set of verses just tell us how evil they've been and make a few pious remarks about not following their example. Rush, on the other hand, is allowed to wax sentimental about his love of the English countryside, place part of the blame for the killing on his victim and feel sorry for himself about Emily Sandford's betrayal.

“My friends and home to me were dear,

The trees and flowers that blossomed near,

The sweet-loved spot where youth began.

Is dear to every Englishman.”

[...]

“If Jermy had but kindness shown,

And not have trod misfortune down,

I ne'er had fired the fatal ball,

That caused his son and him to fall.”

[...]

“Oh, Emily Sandford, was it due,

That I should meet my death through you?

If you had wished me well indeed,

How could you thus against me plead?” (9)

The convoluted history of disputes over Stanfield Hall's proper ownership had left a legacy of resentment in the area, and that may explain why the ballad writers were prepared to give Rush whatever benefit of the doubt they could muster. The biggest potential profits lay in ballads which reflected your buyers' prejudices, and Rush's sales figures suggest they judged the market shrewdly.

Just as with Tawell's case, though, healthy sales for the true story only encouraged balladeers to milk the case a little further. It wasn't long before they'd concocted a fictional confession for Rush, supposedly delivered to the chaplain at Norwich Castle. “The newspapers screeved about Rush and his mother and his wife,” one balladeer told Mayhew. “But we, in our patter, had him confess to murdering his old grandmother fourteen years back and how he buried her under the apple tree in the garden - and how he murdered his wife as well.”

The case was a juicy enough one to inspire several tellings in other media too, including a series of pottery figures and a 1948 movie.