"The community in the vicinity of this tragedy is divided into two separate and distinct classes. The one occupying the fertile lands adjacent to the Yadkin River and its tributaries is educated and intelligent, and the other, living on the spurs and ridges of the mountains, is ignorant, poor and depraved. A state of morality unexampled in the history of any country exists among these people, and such a general system of freeloveism prevails that it is 'a wise child that knows its own father'."

"The community in the vicinity of this tragedy is divided into two separate and distinct classes. The one occupying the fertile lands adjacent to the Yadkin River and its tributaries is educated and intelligent, and the other, living on the spurs and ridges of the mountains, is ignorant, poor and depraved. A state of morality unexampled in the history of any country exists among these people, and such a general system of freeloveism prevails that it is 'a wise child that knows its own father'."

- New York Herald, May 2, 1868, on Wilkes County, North Carolina.

"And so you dance and drink and screw,

Because there's nothing else to do."

- Jarvis Cocker, Common People.

Sometimes, it's not the information a song contains which gives it its power, but precisely what it chooses to leave out.

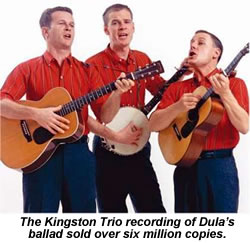

The Kingston Trio's 1958 recording of Tom Dooley scored a top five hit on both sides of the Atlantic and dragged the burgeoning folk revival from a few Greenwich Village cafes to the global stage. It's a sparse 16 lines long - just 82 words in all - and the sheer economy this forces on its bare-bones tale guarantees that the record will raise many more questions than it answers.

We're introduced to a man called Tom Dooley and told he's due to hang tomorrow morning for stabbing an unnamed beauty to death. If it hadn't been for this Grayson fellow, he'd have been safe in Tennessee instead. Listen again, and you may pick up from the spoken word introduction that some sort of romantic triangle was involved.

It's not much, is it? And yet this rudimentary tale was enough to ensure the record sold six million copies round the world, topping the charts not only in America, but in Australia, Canada and Norway too. Only Lonnie Donegan's canny decision to quickly cut his own competing version - itself a sizable UK hit - kept the Trio's original from scoring the top spot in Britain too. Dooley's ballad and the killing that inspired it have been firmly cemented in the public imagination ever since, spilling over into movies, comedy, theatre and every other medium. In his 1997 book Invisible Republic, Greil Marcus calls the Trio's record "insistently mysterious" and suggests it's the very paucity of information it offers which makes the song so fascinating.

The singer clearly sympathises with Dooley - "Poor boy, you're bound to die" - and invites us to do likewise. But how can we oblige when he refuses to tell us who it was that Dooley killed, why he did so or what the extenuating circumstances might be? Where did all this happen? And when? Who was Grayson, how did he thwart Dooley's planned escape and what's so special about Tennessee? And why have these innocent-looking preppy boys, with their short hair, slacks, and crisp stripy shirts, chosen such a violent song?

A quick glance at the discs surrounding Tom Dooley in the US chart that autumn confirms how awkwardly it sat with the era's sugary norm. Dooley's tale of slaughter and despair made a strange bedfellow for Rockin' Robin, Queen of the Hop and The Chipmunk Song. Conway Twitty's cornball country reading of It's Only Make Believe was the single that preceded Tom Dooley at Number One, and it was The Teddy Bears' winsome To Know Him is to Love Him that dislodged it. Small wonder, as Marcus says, that Dooley's disc prompted such a nagging question in listeners' minds whenever it was played: "What is this?"

That question was only heightened by the many bizarre spin-offs which Dooleymania produced. The first to show through were a batch of late fifties "answer songs", such as Merle Kilgore's Tom Dooley Jr, Russ Hamilton's The Reprieve of Tom Dooley and The Balladeers' Tom Dooley Gets the Last Laugh. These were typically facetious attempts to cash in on the original hit's popularity, with The Balladeers' disc, for example, giving Tom an unlikely escape on the gallows. "There on his toes he balanced," it smirks. "They'd made the rope too long".

Columbia Pictures was keen to exploit the original song's success too, and in 1959, they released a film version called The Legend of Tom Dooley. This cast Michael Landon - best-known as Bonanza's Little Joe - in the title role, but cheerfully made up its own story from scratch. In this telling, Dooley and his Confederate army friends are framed for murder after what they take to be an honourable wartime shooting, and Tom kills his unfortunate girlfriend in a tragic accident.

Ella Fitzgerald got in on the act too, slipping an unexpected snatch of Tom Dooley into her 1960 recording of Rudolph The Red Nosed Reindeer. Listeners to that year's A Swinging Christmas album were startled to hear Ella replying to the track's short piano break by singing the improvised lines: "Hang your nose down, Rudy / Hang your nose and cry". If nothing else, this shows how firmly Dooley's ballad had already lodged itself in America's collective mind, and suggests that even the finest jazz singer of her generation had found its chorus ringing through her head.

Still we were no closer to discovering what the true story was. The folk music covers which started to appear in the next couple of years took a more serious approach, but many were content to simply copy The Kingston Trio's template. Where these did manage to slip in an extra bit of information - Lonnie Donegan's reference to "Sheriff Grayson" for example - it often turned out to be untrue.

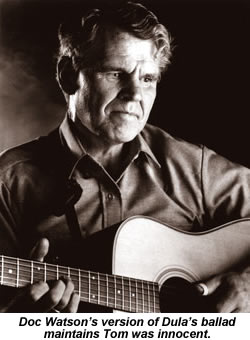

Mike Seeger's New Lost City Ramblers went back to an earlier folk version of the song for their 1961 recording, adding the news that Tom had been a fiddle player, naming his victim as Laura Foster and giving us the rough dimensions of her shallow grave. The blind country singer Doc Watson contributed a third version in 1964 - perhaps an even older one - which claimed Tom was innocent of any crime, and condemned to hang only because someone was determined to persecute him. Just who that someone was, Watson declined to say.

Really determined researchers could consult the few printed sources available with Tom's story, but these proved just as impossible to reconcile as the songs. John and Alan Lomax had included Tom Dooley in their 1947 collection Folk Song USA, printing the same lyrics The Kingston Trio would use eleven years later, but their account of the case behind the song relied more on folklore than fact. Rufus Gardner's 1960 book Tom Dooley: The Eternal Triangle located the tale firmly in North Carolina, but was determined to whitewash the reputation of everyone involved. When the newspapers deigned to print a background article about Dooley's song, they simply reproduced the same mistakes and tall tales these two books contained.

In 1957, no-one outside North Carolina had ever heard of Tom Dooley. Five years on from The Kingston Trio's hit, his name was known around the world, and many millions of people were at least dimly aware that he'd been accused of killing his girlfriend and later hanged for it. Hardcore folk fans may also have grasped that the killing happened in the Wilkes County of 1866. For every 'fact' that emerged, though, there was another one alongside to contradict it, and that meant Dooley's identity in the mass media became more confused every day.

In 1957, no-one outside North Carolina had ever heard of Tom Dooley. Five years on from The Kingston Trio's hit, his name was known around the world, and many millions of people were at least dimly aware that he'd been accused of killing his girlfriend and later hanged for it. Hardcore folk fans may also have grasped that the killing happened in the Wilkes County of 1866. For every 'fact' that emerged, though, there was another one alongside to contradict it, and that meant Dooley's identity in the mass media became more confused every day.

Here was a folk song - a folk song, for God's sake - that had somehow managed to top the charts and sell six million copies. Here was a tale of murder and judicial execution sung by three clean-cut young boys any mother could admire. Here were novelty records, movies, books and a story which contradicted itself with every new telling, and yet never seemed to change. With every drop of a needle onto vinyl, every flickering image of Landon's face on a cinema or TV screen, Marcus's question resounded anew: What is this?

I'm glad you asked...

Captain William Dula came to Wilkes County's Happy Valley in 1790, acquiring several thousand acres of fertile riverside land between the towns we now call Patterson and Ferguson. Dula was a veteran of America's recent War of Independence, and his family soon became part of the rich, educated elite whose fortunes were maintained by their slave-run plantations along the Yadkin River.

Further up the hillsides flanking this land lived a very different class of people. These were the "ignorant, poor and depraved" folk the New York Herald would later be so rude about, and William Dula's brother Bennett lived among them. He owned only a patch of this far less valuable upland property which, although it made him better off than most of his hillside neighbours, still left him well below William's status.

The local dialect meant any name ending in "a" was pronounced with an "ee" at the end instead, transforming the written Dula into "Dooley" when spoken aloud. Nashville, where country music's Grand Old Opera show began in 1925, lies just 300 miles west of Happy Valley, and it's this same habit of local speech that instantly rechristened it the "Opry".

Bennett was Tom Dula's grandfather, and Tom was born in 1844. Just two years later, a man called Calvin Cowles established a general store and Post Office at the mouth of Elk Creek, giving Tom's little community its first central gathering place and the name of Elkville. Cowles's store was the place where any entertainers passing through the county stopped to perform, a mustering ground for the local militia and an ideal spot for any campaigning politicians to gather a crowd. It also served as a makeshift courthouse.

Living about half a mile from Tom's cabin in Elkville was Lotty Foster's brood of five illegitimate children: Ann, Thomas, Martha, Lenny and Marshall. "The entire family was illiterate," John Foster West writes in his 1993 book Lift Up Your Head Tom Dooley. "In addition to her promiscuity, Lotty Foster had a reputation for drunkenness. This is the home Ann Foster Melton had been born into and grown up in until she was married at 14 or 15 to James Melton." (1)

Not long after that marriage, Lotty caught Ann and Tom naked in bed together, at a time when Tom would have been about15 and Ann perhaps a year older. Tom jumped out from between the sheets when Lotty confronted him, tried briefly to hide under the bed, and then fled with the angry woman at his heels. "I ordered him out," Lotty recalled seven years later. "He had his clothes off." (2)

Ann's adultery with Tom did not stop there. Her husband James, a local farmer who also served as the area's cobbler, kept three beds in his single-room cabin, and he often slept alone in one while Tom and Ann shared another. Pauline Foster, Ann's cousin, who occupied the third bed, told the court at Tom's trial she'd often seen Tom slipping into Ann's bed after dark and spending the night with her there. James didn't seem to care. "Ann was a mesmerisingly beautiful creature," Foster West says. "That may have been enough for him. Also, Ann was imperious, aggressive and ferocious when thwarted. That may have contributed to her husband's passivity as well."

Neither Tom nor Ann were short of other bedmates. The descriptions we have of Tom depict a good-looking young man, close to six feet tall, with brown hair and brown eyes. He was handsome enough to regularly bed Ann - by all accounts the area's reigning beauty - and there's no reason to think he'd stop there. Foster West is in no doubt that his character was essentially depraved, with an obsessive lechery that began in childhood.

As for Ann, it was common knowledge in Happy Valley that she slept with any man who took her fancy. "Ann Melton was a unique character, possessing almost all the faults one woman could have," Foster West confirms. "In addition to her promiscuity, she was temperamental, demanding and aggressive. She was also lazy."

Tom was pretty lazy himself. The 1860 census shows his mother Mary as head of the household, suggesting Tom's father was already dead, and leaving Mary with four children to raise alone. The land she owned was valued that year at $195 (about $4,600 today), but much of it was probably rocky scrubland, and Tom showed little interest in cultivating it. His two older brothers, John and Lenny, were a little more industrious, but they both left to become soldiers when the Civil War began in 1861, and neither returned alive.

North Carolina seceded from the Union in May 1861 - the last of the 11 rebel states to do so - but many of those living in Wilkes County had no sympathy for the Confederate cause. Some were outright Unionists, and this led to bitter splits between families and communities which lasted well into the 20th Century. Tom was a Confederate, though, and he signed up for three years in Company K of the North Carolina Infantry's 42nd Regiment in March 1862. It's true that Tom played the fiddle, but not that he served with Colonel Zebulon Vance's 26th Regiment or entertained Vance with fiddle tunes round the campfire at night.

Interviewing Tom's old army companions many years later, a reporter from the New York Herald found they remembered him as "a terrible, desperate character" in those years. As usual, it was Tom's dick that led him into trouble. "Among them, it was generally believed he murdered the husband of a woman in Wilmington during the war, with whom he had criminal intercourse," the Herald's man wrote. (3)

But there was evidence on the other side too. The same paper allowed that Tom had fought gallantly on the Confederate side and won a reputation for bravery there. At least one other Company K veteran, his friend Washington Anderson, was prepared to swear in court that Tom had conducted himself well as a soldier.

But there was evidence on the other side too. The same paper allowed that Tom had fought gallantly on the Confederate side and won a reputation for bravery there. At least one other Company K veteran, his friend Washington Anderson, was prepared to swear in court that Tom had conducted himself well as a soldier.

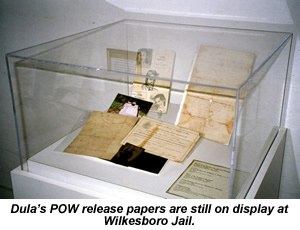

Tom's rank changed from private soldier to musician at the beginning of 1864, indicating that he'd become a drummer, responsible for beating out the charge or retreat in battle and setting the rhythm for marching drills back at camp. He saw quite a bit of action in the year that followed, fighting at Cold Harbour, Petersburg and Kinston. That last engagement proved his undoing, leading to Tom's capture as a POW in March 1865, and three months' stay in a Yankee prison.

The Civil War ended a month or so after Tom was captured, but he remained a POW until June 11. Already, his own regional pronunciation of the family name was causing confusion, and he found the oath of allegiance he was required to sign to the newly-restored USA listed him as "Dooley". He put his mark to that spelling rather than risk his release, but could not resist scrawling "Dula" above it as well.

As hostilities wound down, many of the less enthusiastic Confederate soldiers in Tom's part of the country had fled their regiments to the mountains around Elkville to hide from the former comrades who now wanted to shoot them as deserters. The continuing presence of these men in Wilkes County's hills added to the lawless atmosphere there, and Tom must have wondered what other changes he'd find when he returned home.

The end of slavery meant Happy Valley's aristocrats were a good deal less wealthy than once they'd been, though still a substantial cut above their hill country neighbours. Times were hard in the uplands, with society in ferment at every level, old Civil War resentments still playing themselves out nearby, and starvation a very real prospect for the poor. People in Elkville and a dozen other small communities like it began to replace former slaves on the big plantations, becoming sharecroppers or tenant farmers there, but continuing to live in their own ramshackle settlements.

One of those tenant farmers was Wilson Foster, who shared his own cabin with his daughter Laura. Folklore describes Laura as a beautiful girl with chestnut hair and blue - or green, or brown - eyes. She had very distinctive teeth, slightly larger than average, and with a noticeable gap between her two central incisors. Her mother's death between 1860 and 1866 may explain why Laura had started to run a little wild. By the ripe old age of 22, she'd secured a reputation for "round heels" - a local phrase denoting the ease with which she could be toppled onto her back - and it wouldn't be long before Tom sought her out.

Wilson first found his daughter in bed with Tom in March of 1866, and later testified that the young man had come calling on Laura about once a week. Often, he spent the night with her, alternating his visits there with his now-customary trips to Ann's bed. It was also in March 1866 that Ann's cousin Pauline arrived from the next-door Watauga County to work as a live-in housekeeper at the Meltons' place. Pauline's heels were even rounder than Ann or Laura's, and it wasn't long before Tom was screwing her too.

"I slept

with Dula for a blind at Ann Melton's insistence," Pauline said when questioned about this in court. "I [also] stayed out at the barn with him at his request." Pauline was "remarkable for nothing but debasement," the Herald's reporter declared. Foster West calls her "depraved, immoral and promiscuous," adding that she may also have been an alcoholic.

So, let's review for a moment. In the Spring of 1866, Tom was sleeping with Ann, Laura and Pauline. Ann was also sleeping - at least occasionally - with her husband, and quite possibly a couple of other men as well. Pauline, we know, slept with Ann's brother Thomas, and was said to have bedded her own brother Sam too. Tom's the only bedmate of Laura's we can put a name too, but her reputation suggests there were others.

None of this merry bed-hopping would have mattered much if it hadn't been for one awkward fact. Pauline had syphilis.

Pauline had contracted the disease before leaving Watauga County, and come over the border to Wilkes in search of medical treatment. George Carter, the only doctor for miles around, lived in Happy Valley, and Pauline had taken the housekeeper's job to pay him for the blue mass, blue stone and caustic he prescribed. "I admit I have this venereal disease," she testified years later. "I came to James Melton's to get cured, and worked with him for money to buy medicines." Ann and James agreed to pay Pauline $21 (about $300 today) to stay with them and work throughout the Summer, but she told no-one the real reason for her visit.

It takes about three weeks from catching syphilis to the first appearance of its tell-tale chancre on the penis, and Tom presented precisely that symptom when he visited Dr Carter in the Spring of 1866. "About the last of March or the first of April, the prisoner applied to me for medical treatment," Dr Carter said. "He had the syphilis. He told me he caught it from Laura Foster."

That's probably what Tom believed himself, but he would have known nothing about Pauline's infection. She'd arrived in Wilkes County on March 1 and, assuming a week or so passed before she and Tom first slept together, the timing would be about right for the disease to have come from her. Meanwhile, of course, Tom was still screwing both Ann and Laura, each of whom had other sexual partners of their own.

Soon, Ann and Laura were showing symptoms of syphilis too, and Ann claimed she'd also passed it to James. The local name for this infection was "the pock" and Lord knows how many people may have eventually been caught up in Pauline's chain of disease. Challenged about her health by Ann a few months later, Pauline angrily replied "We all have it!"

For now, though, Pauline's pock was known only to her and Dr Carter. Tom still believed Laura had given him the disease, and told a neighbour in the middle of May that he intended to "put through" the woman responsible. The neighbour, knowing this regional phrase meant Tom planned to kill her, tried to dissuade him.

A week later, Tom visited Laura and spoke privately with her for about an hour. They had another, equally intense, conversation on May 23, leading Laura to tell one of her own neighbours that Tom had promised to marry her. "Very possibly, Laura Foster was pregnant," Foster West says.

On Thursday, May 24, Ann took Pauline to one side, told her Tom had caught the pock from Laura and said that she - Ann - now had it too. Ann told Pauline she was going to kill Laura in revenge, and threatened to kill Pauline too if she ever reported this conversation.

Later the same morning, Pauline was alone at the Melton house, when Tom turned up. He said he'd met Ann on the ridge, and she wanted Pauline to give him some alum for the sores on his mouth and to lend him a canteen. Pauline handed the two items over, and Tom gave the empty canteen to a man called Carson McGuire, telling him to fill it with moonshine liquor.

Tom's next stop was Lotty's place, where he borrowed a heavy digging tool called a mattock. He told Lotty he wanted to "work some devilment out" of himself. Soon after this, a local woman called Martha Gilbert saw Tom swinging the mattock on a path about 100 yards from the cabin he shared with his mother. He told Martha he was working to widen the path there so he could walk more safely at night. Months later, Laura's grave would be discovered about 250 yards from this spot.

Tom's next stop was Lotty's place, where he borrowed a heavy digging tool called a mattock. He told Lotty he wanted to "work some devilment out" of himself. Soon after this, a local woman called Martha Gilbert saw Tom swinging the mattock on a path about 100 yards from the cabin he shared with his mother. He told Martha he was working to widen the path there so he could walk more safely at night. Months later, Laura's grave would be discovered about 250 yards from this spot.

McGuire delivered the full canteen to the Melton house at about 10:00am. Ann took a swig from it, announced she was going to take it to Tom, and then left for her mother's cabin. Tom arrived at Lotty's - without the mattock - soon after Ann, and they left together at about 3:00pm. Neither was seen again until dawn the next day. Lotty asked Tom for her mattock back a couple of times in the days that followed, but he didn't eventually return it until Sunday or Monday.

"It would have been an easy matter for Tom to conceal the mattock in the bushes near the grave site on Thursday," Foster West writes. "He returned to Lotty Foster's later that afternoon without the mattock and he and Ann Melton left together with the canteen of liquor around 3:00pm. Both he and Ann were missing from their homes for the remainder of that day and all of the following night. That was a logical time to dig the grave."

Ann arrived home at about 5:30 on the Friday morning, undressed and climbed into bed. She told Pauline that she, Lotty and Tom had laid out all night and drunk the canteen of liquor. When Pauline got up to prepare breakfast, she could see that Ann's clothes and shoes were wet.

Meanwhile, also at about 5:30, Tom was outside Laura Foster's cabin. Careful not to wake her father, she stepped outside to speak with Tom, and then returned to her bedside, where she quickly got dressed and bundled a few spare clothes together.

Laura was a skilled weaver and often took her payment for this work in the form of cloth, which relatives would later make up into dresses for her. It was one of those dresses she chose now, donning a second one made of store-bought material over it as protection from the early morning cold. She pinned the dresses in place with a broach on her chest, threw a cape over her shoulders to conceal the syphilis welts already showing there, and slipped out the door.

Wilson's mare was tethered outside the cabin. Laura pulled its rope free, climbed on and rode bareback down the riverside track towards the meeting place Tom had chosen. Her bundle of spare clothes was stuffed into her lap.

Laura was just one mile into her six-mile journey when she met Betsy Scott, the same neighbour she'd confided in a few days before, and told her she and Tom had agreed to meet at a spot in the woods where an old blacksmith's shop had once stood. All trace of that shop had vanished now, but the site was still known by the name of the man who'd owned it. Everyone around knew just where "Bates' Place" was, and that's where Laura was heading now. Betsy, perhaps thinking how short-lived a promise of marriage from a man like Tom was likely to prove, urged Laura to hurry along. "I said if it was me, I'd have been further on the road by this time," Betsy later recalled. (2)

Meanwhile, Tom was walking along a path parallel to Laura's track on his way to the Meltons' place. He stopped briefly to chat with neighbours three times along the way and, when one of them asked if he was pursuing his plans for revenge against Laura, replied "No, I have quit that". Pauline was already out and working when Tom arrived at the Meltons', but returned to the cabin just after 8:00am for a milk pail, when she found Tom bending over Ann's bed, talking to her in low, urgent tones.

Wilson

was up and about by then too, and angry to find that both his daughter and his mare had gone missing. He'd been trimming the mare's hooves that week, and left one of them half-finished, giving it a distinctive pointed shape that was easy to track in the soft ground. He followed its progress all the way to Bates' Place, but lost the tracks there in an old field.

He cadged some breakfast at a friend's house nearby - complaining about the loss of his mare throughout the meal - and then walked on to the Meltons' cabin, where he found Ann still in bed. Tom had just left, stopping to collect half a gallon of milk at Lotty's cabin and then walking off down Stony Fork Road in a direction which could take him either to his own house or to Bates' Place. As always, he carried a six-inch Bowie knife in his coat pocket.

Tom wasn't seen again till noon, when Mary Dula returned to the cabin they shared to find her son already there, lying in bed. They ate their noon meal together, and Tom remained in Mary's company until about 3:00pm, when she went out for a short while to deal with the cows. A couple of Tom's friends met her out working and asked where Tom was, but Mary said she didn't know.

That evening, while Mary prepared supper, Tom went out. Mary assumed he was in the barn, but Ann's mother Lotty and her brother Thomas both testified later that they'd seen Tom heading up to Bates' Place at about that time. The distance from the Dula cabin to Bates' Place was about a mile, so Tom could have walked it in 20 minutes or so if he'd kept up a brisk pace.

He returned home in time to eat his supper, but then went out again just after dark, staying out for what Mary said was about an hour. When he returned, he complained of chills as he prepared for bed, and Mary heard him moaning in the night.

We have Wilson's evidence that Ann was still in bed at home around 8:30 on Friday morning, but no other accounts of her movements until nightfall, when Wilson returned to the Melton's place for a party with Ann, James and Pauline. Ann's brother Thomas was there too, along with three other men. "Everyone was joking and having a good time," Wilson said.

Pauline later claimed that Wilson had announced that evening he didn't care what happened to Laura as long as he got his mare back, and even threatened to kill the girl if he ever found her. Wilson denied saying any such thing, but Pauline stuck to her guns in court, saying she'd jokingly replied with an offer to go and find Wilson's mare herself if he'd give her a quart of liquor for doing so.

Wilson stayed at the Melton's party for two or three hours, and then spent what was left of the night at his friend Francis Melton's place. When he returned to his own cabin on Saturday morning, he found his mare already waiting there. It had chewed through its halter rope, about three feet of which was still hanging from the headcollar. No one ever saw Laura alive again.

All we can say for sure about what happened to Laura that day is that she was dead by the end of it. But it was almost certainly Tom who stabbed her.

There will be those of you who bridle at that, so let me explain why I'm so confident. US murder statistics from 1999 show that 87.5% of all America's murders are committed by men, and that 23% of all homicides there have a male perpetrator and a female victim. Only 2.5% of all US murders have a woman as both perpetrator and victim. That doesn't mean it's impossible that Ann killed Laura, of course, but it does put the burden of proof firmly on those who argue for her guilt rather than Tom's.

Even if we discount the rumours of Tom murdering his Wilmington lover's husband during the war, we know he saw enough battlefield slaughter to risk brutalising any man. The Herald tells us that the Tom Dula who returned to Happy Valley in 1865 was "reckless, demoralised and a desperado, of whom the people in his vicinity had a terror". As we'll see in a moment, his first reaction on hearing local people suggest he might have killed Laura was to threaten them with a beating.

Those who insist Ann was the murderer have some sentimental folklore on their side, but precious little else. The idea that Tom went willingly to the gallows to protect Ann from hanging instead gives an element of noble romantic sacrifice to his story which some people are determined to maintain at all costs. Ann may well have helped Tom dig the grave, and even to bury the body too, but the truth of Laura's killing itself is probably as simple and as squalid as most murders are. Here's how Foster West sees it:

"Sometime on that Friday, Tom met Laura in the woods. In one quick, forceful motion he plunged into her chest cavity the long blade of a knife. Then, perhaps with the help of Ann, he transported the body about half a mile to the grave he had dug with the mattock the night before. Into that hole, about two and a half feet deep, he dumped the body on the right side with the legs drawn up."

Deciding just when Tom stabbed her that day is more difficult, because every scenario presents its own snags. He could have killed Laura as early as 9:00am, straight after his stop at Lotty's cabin, but burying her then would have meant moving the body on his own in broad daylight.

Concealing the body at Bates' Place and then returning after dark to move it with Ann's help sounds more likely but, as Foster West points out, that raises the problem of rigor mortis, which may have made it impossible to bend Laura's knees enough to squeeze her into that tiny four-foot grave. Frances Casstevens, author of Death in North Carolina's Piedmont, claims Laura's legs were broken to fit her in the grave, but no other account mentions this, and I take it to be a little gratuitous cruelty slipped into the story for its shock value alone.

Concealing the body at Bates' Place and then returning after dark to move it with Ann's help sounds more likely but, as Foster West points out, that raises the problem of rigor mortis, which may have made it impossible to bend Laura's knees enough to squeeze her into that tiny four-foot grave. Frances Casstevens, author of Death in North Carolina's Piedmont, claims Laura's legs were broken to fit her in the grave, but no other account mentions this, and I take it to be a little gratuitous cruelty slipped into the story for its shock value alone.

Foster West speculates that Tom may have met Laura at Bates' Place early in the day, given her a jug of moonshine to keep herself entertained, and persuaded her to wait for him there until nightfall. He would have returned either before or after supper - perhaps with Ann in tow - and killed Laura then.

This would at least allow Tom and Ann to transport the body in relative safety, and bury her before rigor mortis set in. But it takes a bit of believing to think a wild girl like Laura would have meekly waited in the woods all day while her lover was off doing God knows what. Far from helping matters, I'd have thought the moonshine would just make her more volatile.

Tom returned to the Meltons' cabin on Saturday morning, telling Pauline he'd come to collect his fiddle and get his shoes repaired by James. He spent half an hour talking quietly with Ann and then, when Pauline said she thought he'd run off with Laura, laughed and said: "I have no use for Laura Foster".

Later that morning, Ann told Pauline that she'd gone out during the night and that neither Pauline nor Thomas, who'd shared Pauline's bed that night, had missed her. "She'd done what she said," Pauline later claimed Ann had told her. "She'd killed Laura Foster."

When the news got out about Laura's disappearance, many people assumed, like Pauline, that she and Tom had run off together. As soon as they realised Tom was still in Elkville, gossip started to spread that he must have murdered her, and neighbours noted his refusal to join the search parties. By June 22, nearly a month after Laura's death, a local family called Hendricks was openly telling everyone around them that Tom had killed Laura. When James reported this gossip to Tom, he laughed again and said "They will have to prove it. And perhaps take a beating besides!"

Two days later, calls for Tom's arrest were circulating, and Happy Valley's citizens organised their biggest search party yet. This was led by a man called Winkler, who formed everyone up into a long line and told them to walk slowly up the ridge from Mary Dula's house towards the north, examining the ground as they went. Arriving at Bates' Place, they found a piece of rope tied to a dogwood tree, which had been chewed through at its dangling end and which matched the rope Wilson's mare had trailed home.

They found a couple of piles of horse dung nearby too, showing the mare had stood there for some time, and also a discoloured patch of ground which they decided had been stained by Laura's blood. "The discolouration of the ground at this spot extended the width of my hand," Winkler later explained. "The smell of the earth was offensive, and different from that of the surrounding earth."

Next day, Tom went to confront the Hendricks family, and then called at the Meltons' place around nightfall. He spoke privately to Ann outside - Pauline could see that they were both weeping - and then came back in to retrieve a knife Ann had hidden for him under one of the cabin's bedheads. When Pauline asked what was wrong, Tom said the Hendricks clan was telling lies about him, falsely claiming that he'd killed Laura, and that meant he was going to have to get out of Wilkes County. He'd be back at Christmas to collect his mother and Ann, he promised, and then the three of them would find somewhere safer to live.

After a final tearful embrace between himself and Ann, Tom told her goodbye and left. He stopped in Watauga County for a few days, probably staying with relatives there, gave himself the new name of Tom Hall, and then walked on towards Tennessee.

Tom had already been in Watauga for three days when William Hix, the Wilkes County sheriff, received a warrant from Elkville's Justice of the Peace, Pickens Carter. This ordered Hix to arrest Tom, Ann and two of Tom's second cousins on suspicion of murdering Laura. All but Tom were quickly rounded up, and brought to Carter's June 29 hearing at Cowles Store, where he found the three of them not guilty. Carter also dispatched two Elkville deputies, Jack Adkins and Ben Ferguson, to track Tom down and bring him home.

Tom spent the best part of a week walking through the mountains into Tennessee, arriving at a town called Trade, about ten miles south east of Mountain City, on July 2. He pitched up at a farm owned by Colonel James Grayson, a former soldier who now sat in Tennessee's state legislature, and got himself a job there as one of Grayson's field hands. He worked there for about a week - long enough to earn what he needed to replace his ruined boots - and then walked off west towards Johnson City.

Carter's two deputies arrived at Grayson's farm a few days after Tom had left, and Grayson realised that the man they were describing was the field hand he'd known as Tom Hall. According to James Rucker's article in the Winter 2008 issue of Appalachian Heritage, Grayson rode off with Adkins and Ferguson to find Johnson County's sheriff, knowing they'd need his authority to arrest Tom outside their own North Carolina jurisdiction. Discovering the sheriff was away on official business, the three men decided to ride on after Tom themselves.

They found him camped by a creek at Pandora, about nine miles west of Mountain City. Grayson dismounted, told Tom he was under arrest and Tom, seeing that Grayson carried a gun, surrendered. Rucker adds that Adkins and Ferguson were both keen to hang Tom on the spot, and says it was only Grayson's insistence on due process that stopped them.

Grayson mounted Tom behind him on his horse, tying his feet beneath its belly to keep him there, and the four men rode off back to Trade. Arriving at Grayson's farm, they locked Tom in a corn crib overnight and sent Grayson's 12-year-old son out to guard the door. Next day, they made the trip back to Wilkesboro - foiling at least one escape attempt by Tom en route - and locked him in the jail cell there which tourists still visit today. With no corpse yet found, the police still had no firm proof a murder had even been committed, but no-one seemed to think that was worth worrying about.

Hearing of Tom's capture on July 14, Pauline fled from Elkville across the county border back into Watauga. Ann followed her there a few days later with Pauline's brother Sam, explained forcefully that Pauline's flight was just making them all look guilty, and bullied her into accompanying them back home.

Even with Pauline back in the fold, though, Ann was still worried. She approached Pauline in tears one day in early August, said she was afraid Tom might hang, and urged Pauline to help her ensure no further evidence against him came to light. "I want to show you Laura's grave," she said. "I want to see whether it looks suspicious."

Ann insisted that Pauline must come with her, saying first that she would dig up Laura's body if the grave looked suspicious and rebury it in her cabbage patch, then deciding it might be better to cut the body into bits and dispose of it that way. Ann led Pauline from the Melton's cabin past Lotty's place and across Stony Fork Road to a pine log part way up what is now Laura Foster Ridge. She paused there to shuffle some dead leaves over a spot which looked like it had been rooted up by some hogs, but told Pauline that the actual grave was higher up the ridge. Pauline was thoroughly spooked by now, however, and refused to go any further.

Ann insisted that Pauline must come with her, saying first that she would dig up Laura's body if the grave looked suspicious and rebury it in her cabbage patch, then deciding it might be better to cut the body into bits and dispose of it that way. Ann led Pauline from the Melton's cabin past Lotty's place and across Stony Fork Road to a pine log part way up what is now Laura Foster Ridge. She paused there to shuffle some dead leaves over a spot which looked like it had been rooted up by some hogs, but told Pauline that the actual grave was higher up the ridge. Pauline was thoroughly spooked by now, however, and refused to go any further.

Realising Pauline was adamant, Ann marched on alone. She returned a few minutes later, apparently having satisfied herself the grave would draw no attention, and cursed Pauline for her cowardice all the way back home.

Pauline was falling apart fast now, tormented by the knowledge that she was probably responsible for the infection that had led to Laura's murder, and often drunk enough to make her more unpredictable than ever.

About a week after their trip to the grave, Ann and Pauline were together at the Meltons' cabin when the two deputies, Adkins and Ferguson, came to question them both. Ferguson said he believed Pauline had helped kill Laura, and that was why she'd fled across the county line. Pauline, who'd been drinking, answered: "Yes, I and Dula killed her, and I ran off to Watauga County. Come out, Tom Dula, and let us kill some more! Let us kill Ben Ferguson!" Seeing the state Pauline was, Adkins and Ferguson were not inclined to take this outburst seriously, and Pauline herself later insisted it had been meant as a joke. But Ann could see that her cousin was now someone she couldn't afford to trust.

A few days later, Pauline was visiting a neighbour when Ann pursued her there with a club. She demanded that Pauline come home with her immediately, pushed her out of her chair towards the door and said she'd wanted to kill her ever since Pauline's stupid words to Ben Ferguson. "You have said enough to Jack Adkins and Ben Ferguson to hang you and Tom Dula if it was ever looked into," Ann screamed, pinning Pauline to the ground outside and beginning to choke her. "You are as deep in the mud as I am in the mire!" Pauline screeched back.

Ann dragged Pauline 100 yards down the road towards home, then stalked back and threatened the terrified neighbour, demanding she tell no-one about what she'd heard. She began to walk off again, but then returned a second time, warning the woman that she'd follow her to hell itself for revenge if word of that day's fight with Pauline ever got out.

It was obvious now that Pauline was close to cracking, and the police decided that a few nights in jail could be just the push she needed. They arrested her and told her that she, like Tom, was being held on suspicion of Laura's murder. Questioned both in Wilkesboro jail and before a magistrate at Cowles Store, she told police all about her trip towards the grave with Ann, and agreed to help the next search party find Laura's remains.

The chosen day was Saturday, September 1, when a party of over 70 men followed Pauline to the pine log where she and Ann had parted company. Pauline pointed up the ridge in the direction Ann had gone, and the men split into pairs for the search that followed. One of the pairs climbing on that day was Colonel James Isbell and his father-in-law David Horton. Isbell was William Dula's grandson, and hence a member of Happy Valley's riverside aristocracy. His plantation included the Caldwell County farm where Laura had lived with her father, which may explain why he was particularly determined to bring her killer to justice.

Horton was then aged 74, and so conducted the search on horseback, rather than walking like his younger companions. He and Isbell searched their section of the ridge meticulously for an hour and then, about 75 yards on from the log where they'd started, his horse began to snort and rear up. Isbell's grandson, Reverend Robert Isbell, describes what followed in his 1955 book The World of My Childhood.

"My father, James Isbell, noticed the horse back and shy away," Robert writes. "He called to Major Horton to rein the horse back to the spot he had shied from, and when he did the horse refused to go. My father said he went forward and stamped the spot with his boot heel, turned up a side of turf and found Laura about two feet under the ground." (4)

James Isbell gave his own account of this moment at Tom's trial. "After taking out the earth, I saw the print of what appeared to have been a mattock in the side of the grave," he said. "The flesh was off the face. Her body had on a checked cotton dress and dark-coloured cloak or cape. There was a bundle of clothes laid on her head. There was a small breast pin."

The two men summoned Dr Carter over, and he examined the body where it lay, finding the slit of a knife in the fabric over Laura's left breast and a corresponding stab wound between her third and fourth ribs. Laura had already been in the ground for three months by that time, and her body was too decomposed for Carter to tell for sure whether the knife had penetrated her heart or not. He confirmed, however, that it certainly could have reached the heart, and that such a wound would have killed Laura outright.

"The body was lying on its side, face up," Carter testified. "The hole in which it lay was two-and-a-half feet deep, very narrow and not long enough for the body. The legs were drawn up." He made no mention of the legs being broken, nor of any indication he could see that Laura had been pregnant. This did not stop the New York Herald floating the pregnancy theory again when it reported Laura's discovery, but the paper could produce no evidence to support this.

The body was taken back for an inquest at Cowles Store and formally identified by both Pauline and Wilson, who recognised Laura by the gap in her teeth and what was left of her clothes. Ann was arrested and given the same Wilkesboro cell next to Tom's which Pauline had just vacated.

The discovery of Laura's body gave her story a convenient punctuation point, and that's when the case's first ballad emerged. This was written by Happy Valley's Captain Thomas Land, who Gardner calls "a local poetical celebrity".

Land does not mention Tom or Ann by name in the 84 rather plodding lines he composed, and his effort bears no resemblance to the Tom Dula song we know today. But he is clear that Laura was murdered by the lover she'd hoped to marry, and that this man did not act alone:

"'Ere sun declined toward the west,

She met her groom and his vile guest,

In forest wild, they three retreat,

And hope for parson there to meet." (5)

The local audience who first read Land's verses would have known full well that Tom was the groom he had in mind, and been equally sure that his "vile guest" must be Ann. Throughout the poem, Land shows the pair acting together in Laura's murder and disposal, using plural phrases like "those who did poor Laura kill", "they her conceal" and "to dig the grave they now proceed". By doing this, he ensures that Ann is thoroughly implicated in the whole rotten business.

The local audience who first read Land's verses would have known full well that Tom was the groom he had in mind, and been equally sure that his "vile guest" must be Ann. Throughout the poem, Land shows the pair acting together in Laura's murder and disposal, using plural phrases like "those who did poor Laura kill", "they her conceal" and "to dig the grave they now proceed". By doing this, he ensures that Ann is thoroughly implicated in the whole rotten business.

Laura herself is depicted as a sweet, innocent girl, too full of childlike love to imagine Tom could ever wish her harm:

"Her youthful heart no sorrow knew,

She fancied all mankind were true,

And thus she gaily passed along,

Humming at times a favourite song."

Happy Valley's residents would have known that the real Laura was a good deal raunchier than that, but swallowed the lie for the extra narrative satisfaction it offered. The more of a saint Laura could appear, the more villainous Tom and Ann looked by comparison, and that's what delivered the story's disreputable thrill.

Land takes us - somewhat laboriously - through the various stages of Laura's discovery, then closes with a bit of tidy alliteration and one last pious thought to ensure we don't have nightmares:

"The jury made the verdict plain,

Which was, poor Laura had been slain,

Some ruthless fiend had struck the blow,

Which laid poor luckless Laura low.

"Then in a church yard her they lay,

No more to rise till Judgement Day,

Then, robed in white, we trust she'll rise,

To meet her Saviour in the skies."

Land's poem, which he called The Murder of Laura Foster, was written to be read rather than sung, but I have heard one musical setting of it. This appears on Sheila Clark's 1986 album The Legend of Tom Dula and Other Folk Ballads, where Clarke gives us a lovely a capella rendition of Land's full 21 verses, with nothing but a short fiddle phrase to divide each of its three sections. She negotiates the more awkward lines with admirable style, and it's a tribute to the sweetness of her voice that the track's nine minutes and fifteen seconds passes so pleasantly.

Formal legal proceedings against Tom and Ann began on October 1, 1866, when North Carolina's superior court met at Wilkesboro under Judge Ralph Buxton. The charges they made against Tom said he "feloniously, wilfully and of malice aforethought did kill and murder [Laura Foster] against the peace and dignity of the state". Ann was charged that she "did stir up, move and abet, and cause and procure, the said Thomas Dula to commit the said felony and murder," and then chose to "receive, harbour, maintain, relieve, comfort and assist" him.

In other words, Tom was accused of killing Laura, and Ann was charged with both encouraging him to commit the crime and harbouring him afterwards. The prosecution quickly agreed to drop Ann's harbouring charges, leaving just the first accusation against her.

Tom and Ann were brought to the courthouse so they could hear the indictments read against them, and then both returned to Wilkesboro jail to wait for trial. Dr George Carter, James Melton, Wilson Foster, Lotty Foster, Jack Adkins, Ben Ferguson, Pauline Foster and Betsy Scott were all among the witnesses who'd be called.

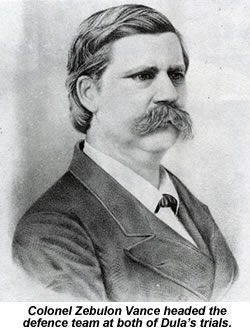

It's still not clear how Tom managed to recruit Colonel Zebulon Vance to defend him, but it certainly represented a bit of coup. Vance came from a military family, and had been elected to Congress twice before the Civil War cut his second term short. He commanded the 26th Regiment of North Carolina's Infantry in battle for a while - not the 42nd where Tom served - and then spent the remainder of the war serving two terms as state Governor. He was arrested by the victorious Federalist forces in May 1865, spent two months in their jail, and returned to freedom an almost penniless man. He began his Charlotte law practice in March 1866, the same month Tom discovered he'd contracted syphilis.

We've got the court's confirmation that Tom was insolvent just three weeks after his indictment was read, so he was clearly in no position to pay Vance for his services. Whether that means Vance was paid by the state, or whether he conducted the defence for free, I don't know. More intriguing is why he agreed to take the job on at all.(5.5)

As we've seen, the rumours that Vance agreed to defend Tom because the two men had served together - or even because he'd enjoyed Tom's fiddle playing round the campfire - do not stand up to the scrutiny of Tom's military records. Gardner says it was Colonel James Horton, one of Tom's many cousins in the area, who asked Vance to get involved, but that seems a pretty flimsy motivation on its own.

As a Congressman, Vance had been against North Carolina's secession, and stood on a Conservative ticket against the Confederacy's man. No doubt he had a certain amount of sympathy for any Confederate soldier down on his luck, but we can dismiss the notion that he was a rabid Johnny Reb, determined to defend any secessionist veteran for that reason alone. That's not to say, however, that Civil War politics were completely irrelevant to his decision.

"North Carolina was 'occupied' by a federal army during the first trial," Foster West points out. "Members of the prosecution were also Republican 'conquerors'. Members of the defence were Democrats and losers of the war. [...] It is interesting to note that all the members of the defence in Tom Dula's first trial had been officers in the Confederate Army, whereas none of the members of the prosecution had served in the military during the war." You couldn't ask for a clearer dividing line that that.

Tom's Wilkesboro trial began on October 4, and Vance got the ball rolling by arguing that feelings against Tom and Ann were running so high in Wilkes County that a change of venue was required. "The Public mind has been so prejudiced against them to such an extent [in Wilkes] that an impartial and unbiased jury could not be obtained," he told Judge Buxton.

The court agreed, and arranged for the trial to be moved across the Iredell County line to Statesville, about 30 miles away. Vance had lost Wilkes County in his most recent Governor's race, but won the vote in Iredell, so this move was good news for the way a Statesville jury might view Dula's attorney too.

A week later, Sheriff Hix moved Tom and Ann to Statesville jail, a old building on Broad Street with a pillory, whipping post and stocks out front. Iredell's county sheriff was concerned this jail might not be secure enough to hold Tom, so the county agreed to pay for eight extra guards to be stationed there during his stay. That would have been a considerable expense, and the fact that Iredell's authorities were prepared to bear it is one more bit of evidence that they considered Tom a very dangerous man.

The Statesville proceedings began on October 15, 1866, again with Judge Buxton presiding. He had a reputation as a cautious but meticulous man, careful in his interpretation of the law, and anxious to be accurate in his rulings. Twelve jurors were selected from panel of 100 Iredell County freeholders - all men - and Vance stood up to speak once again.

This time, his point was that Tom and Ann's cases should be heard as two completely separate trials. Ann had made several incriminating statements since Laura's death, he pointed out, and often these statements had been made when Tom had no opportunity to instantly challenge them. Allowing those statements to be heard as part of the evidence in a joint trial would inevitably make Tom look guilty too, Vance said. The judge agreed, and Tom was tried alone from that moment onwards. Ann's own trial would have to wait.

This time, his point was that Tom and Ann's cases should be heard as two completely separate trials. Ann had made several incriminating statements since Laura's death, he pointed out, and often these statements had been made when Tom had no opportunity to instantly challenge them. Allowing those statements to be heard as part of the evidence in a joint trial would inevitably make Tom look guilty too, Vance said. The judge agreed, and Tom was tried alone from that moment onwards. Ann's own trial would have to wait.

These preliminaries dealt with, District Attorney Walter Caldwell gave his opening statement. The state's case, he said would be that "a criminal intimacy" had existed between both Tom and Laura and Tom and Ann. He expected to show that Tom had caught syphilis from Laura, that he'd communicated that disease to Ann, and that his own infection had prompted Tom to threaten Laura's life as an act of revenge. "By these circumstances and others, I expect to prove Thomas Dula, the prisoner, committed the murder, instigated thereto by Ann Melton, who was prompted by revenge and jealousy," Caldwell told the jury.

The trial had lined up 83 witnesses in all, though it's not clear how many were actually called. All the key players I've mentioned above were heard, though, and gave their evidence just as I've already quoted it. Pauline's declaration when first arrested that she would "swear a lie any time for Tom Dula" now seemed forgotten. It's possible that the police secured Pauline's co-operation by telling her any failure to testify against Tom would place her in the dock beside him. Despite her questionable character, the prosecution certainly relied heavily on Pauline's testimony, which fills a third of the summary transcript Buxton later prepared.

"The witnesses generally appeared impressed with the idea that Dula was guilty," the Herald later reported. "Though some of them appeared anxious to affect an acquittal through fear of some of his reckless associates in the mountains."

Ann was allowed to attend the court throughout Tom's trial but not to testify. Even so, Buxton allowed statements she'd made to various witnesses to be admitted in evidence at Tom's trial, and over-ruled Vance's objections every time he challenged this. It's hard to reconcile this with his reputation for meticulous care, and some take Buxton's rulings as evidence that the law was determined to railroad Tom for a crime he didn't commit.

Vance made the most of Tom's Civil War record throughout the trial, and deployed his considerable eloquence when the prosecution took to mentioning Laura's "lonely grave on the hillside". Vance's reply was that, before sending Tom to hang, they had best decide whether they wanted to see one lonely grave on that hillside or two. "Throughout his trial, Tom always maintained he was innocent, and refused to implicate anyone," Casstevens says. "Attorney Vance portrayed Laura Foster as a woman of loose morals, and Tom as a brave soldier who had been seduced by her." (6)

Closing his case for the defence, Vance asked Buxton to instruct the jury that any circumstantial evidence they used to convict "must exclude every other hypothesis" and remind them they must be convinced of Tom's guilt beyond any reasonable doubt. Buxton agreed, and told the jury exactly that. After hearing two days of evidence, they retired just after midnight on Saturday, October 20, and spent the rest of night deliberating the case.

The jury returned at daybreak with a verdict of guilty. "Governor Vance and his assistant counsel for the defence made powerful forensic efforts which were considered models of ability," the Herald told its readers. "But such was the evidence that no verdict other than that of guilty could be rendered."

The Wilmington Daily Dispatch agreed, saying: "All the evidence that led to the conviction was entirely circumstantial, but so connected by a concatenation of circumstances as to leave no reasonable doubt on the minds of the jury". The Salisbury North State added breathlessly that the evidence presented had been "of the most thrilling character". (7, 8)

Buxton set Tom's execution date for November 9, when he'd be "hanged by the neck until he be dead". That appointment looked unlikely to be met, though, because Vance had already appealed for a new trial on the grounds that Buxton had admitted a good deal of evidence he should not have allowed the court to hear. The judge agreed to refer this request to North Carolina's Supreme Court, but rejected the stay of judgement Vance had also requested. In the unlikely event that Tom's bid for a new trial could be definitively ruled out in just 19 days, his November 9 execution date would still go ahead.

There were no court stenographers taking a verbatim transcript in North Carolina's courts back in 1866, so Buxton worked with clerk of the court CL Summers to prepare a condensed brief summing up the trial, which used testimony from 18 of the witnesses called. It's this summary which went to North Carolina's Supreme Court with Dula's appeal, and which still provides our best record of the trial today.

The fact that Tom had now been convicted of Laura's murder meant Wilkes County's balladeers felt free to name him as her killer. Not only that, but Buxton's sentence meant they could stir the prospect of Tom's execution into their lyrics too.

Frank Brown's collection of North Carolina Folklore, gathered between 1912 and 1943, includes three versions of Tom Dula contributed by a woman called Maude Sutton of Lenoir in Caldwell County. Land's ballad is the first one Sutton discusses in her letter, but it's her second entry which interests us here. "It was very popular in the hills of Wilkes, Alexander and Caldwell Counties in 1867," she says. "Many mountain ballad singers still sing it."

Sutton then quotes three verses from the song she'd just described, which were evidently sung to the same tune we know today:

"Hang down your head Tom Dula,

Hang down your head and cry,

You killed poor Laura Foster,

And now you're bound to die.

"You met her on the hilltop,

As God Almighty knows,

You met her on the hilltop,

And there you hid her clothes.

"You met her on the hilltop,

You said she'd be your wife,

You met her on the hilltop,

And there you took her life." (9)

Sutton had collected this version from a Lenoir man called Calvin Triplett, a surname which Ann's mother used on some early census forms. We don't know exactly what Calvin's relationship to the family was, but it's reasonable to assume he was kin of some sort.

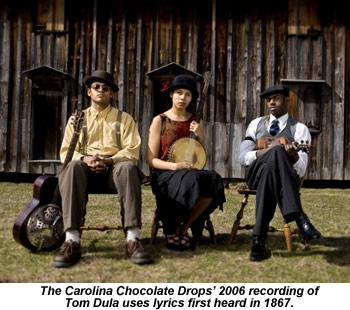

It's also unclear whether Sutton's three verses comprise the whole of the song as she found it, or just the first half. The 1867 verses she quotes, though, still survive almost untouched in many modern readings of the song. The Carolina Chocolate Drops, for example, open their 2006 recording of Tom Dula with these 12 lines:

It's also unclear whether Sutton's three verses comprise the whole of the song as she found it, or just the first half. The 1867 verses she quotes, though, still survive almost untouched in many modern readings of the song. The Carolina Chocolate Drops, for example, open their 2006 recording of Tom Dula with these 12 lines:

"Hang your head Tom Dooley,

Hang your head and cry,

Killed poor Laura Foster,

And now he's bound to die.

"You took her on the hillside,

Where you begged to be excused,

You took her on the hillside,

Where you hid her clothes and shoes.

"You took her on the hillside,

For to make her your wife,

You took her on the hillside,

And there you took her life." (10)

Sutton seems to have seen this coming. "The story is just the kind to be written in a ballad and sung for generations," she wrote in her letter to Brown. "It has all the ballad essentials: a mystery death, an eternal triangle and a lover with courage enough to die for his lady."

The third ballad she contributes is the one which folklore insists Dula composed himself, and sang to the waiting crowds on his way to the gallows. We'll come to the Herald's comprehensive report of Tom's execution a bit later, but it certainly doesn't mention any incident like that.

Sutton's third ballad also opens by giving Tom an instrument no one in the historical record ever mentions him playing:

"I pick my banjo now,

I pick it on my knee,

This time tomorrow night,

It'll be no use to me." (9)

The remaining five verses, all narrated by Tom in the first person, tell us that the banjo's helped him pass the time in jail, that Laura used to enjoy hearing him play it, and he was too much of a fool to realise how much she loved him. It's only the opening verse that still survives today though, sometimes with the instrument corrected to become a fiddle before it's allowed a place in the main ballad. Banjo or fiddle, the sentiment remains constant, as in this verse from The Elkville String Band's 2003 recording:

"You can take down my old fiddle boys,

And play it all you please,

For at this time tomorrow,

It'll be of no use to me." (11)

By 1867, then, we've already got much of the ballad we know today. The chorus The Kingston Trio made famous is already 90% complete, and at least one of their three verses is substantially finished too. As Tom waited in Statesville jail for news of his appeal, the balladeers were still at work, and it wouldn't be long before they had the song's remaining elements in place.

North Carolina's Supreme Court ruled that Buxton had been wrong to admit some of the evidence he'd allowed his jury to hear, and granted Tom a new trial as a result. The new trial date was set for April 17, 1867, and Tom had to wait in jail with Ann until that day arrived.

In fact, he had to wait a lot longer that that. When the Supreme Court gathered on April 17, three of the subpoenaed witnesses failed to turn up. Vance argued that these three individuals' testimony was crucial to his client's case, and persuaded Judge Robert Gelliam to postpone the trial till October 14 as a result. The court then met only twice a year - Spring Term and Fall Term - so this was simply the next date available.

There's a hint of opportunism in Vance's actions here, as one of the missing witnesses was FF Hendricks - presumably a member of the same family that had gossiped about Tom's guilt back in Happy Valley. It's hard to imagine that his testimony would have done anything but hinder Tom's case, so perhaps Vance simply seized on any opportunity to win his client a delay. Six months till the next trial meant six months more life for a man so close to execution, and why waste a chance at that?

When October 14 came round, it was the prosecution's turn to object. This time, the missing witnesses were James Simmons, Lucinda Gordon and James Grayson, each of whom the court fined $80 for failing to attend. Caldwell won his bid for another continuance, but this time the court decided on drastic action. It would set up a special Court of Oyer et Terminer ("hear and determine") to clear the state Supreme Court's growing backlog, and that court would hear Tom's case on January 20, 1868. By that time, Laura would have been dead for 20 months.

The new court convened on time, with Judge William Shipp presiding. Shipp had been a member of North Carolina's General Assembly before the Civil War and a signatory to the state's secession ordinance. He'd raised a Confederate company during the war, acting as its captain in battle, and been a state senator since 1861. He'd been a judge for about six years when this final Dula trial began, and practiced law since 1843.

Another jury was selected and sworn in on the court's first day, and the trial proper began on Tuesday, January 21. The evidence presented was much the same as that heard at Tom's first trial - presumably without the inadmissible stuff Buxton had allowed - and the new jury found Tom guilty all over again.

Shipp set Tom's nominal execution date for February 14, but granted Vance's request to appeal his Oyer et Terminer court's decision. On April 13, 1868, North Carolina's Supreme Court ruled there was no error in Shipp's proceedings, and set yet another execution date for Tom. This time the date - May 1, 1868 - would stand.

Eliza Dula, Tom's sister, arrived at Statesville jail with her husband on the night before the hanging. Ann was still in jail too, waiting for her own trial, but Tom refused to say anything that would either implicate her in Laura's murder or clear her from it. Eliza passed Tom a note via his jailers, which contained his mother's plea that he should at last tell the full story behind Laura's death. Only this, Mary Dula said, would give her the peace of knowing once and for all whether her son was a murderer or not. Tom asked the jailers if he could speak to Eliza in person but, when this was refused, opted to say nothing more.

The case was attracting international attention now, with even regional British newspapers like the Hampshire Telegraph and the Sheffield Independent finding room for it. It was already recognised as one of America's most famous crimes of passion, and the New York Herald thought only Harvey Burdell's high society murder in 1857 could stand comparison. The Herald was so confident of the Dula case's appeal that it dispatched a reporter to Statesville to give readers a first-hand description of Tom's final hours.

The case was attracting international attention now, with even regional British newspapers like the Hampshire Telegraph and the Sheffield Independent finding room for it. It was already recognised as one of America's most famous crimes of passion, and the New York Herald thought only Harvey Burdell's high society murder in 1857 could stand comparison. The Herald was so confident of the Dula case's appeal that it dispatched a reporter to Statesville to give readers a first-hand description of Tom's final hours.

"He still remained defiant, nor showed any sign of repentance," the paper's man said of Tom on that final evening. "He partook of a hearty supper, laughed and spoke lightly. But, ere the jailer left him, it was discovered that his shackles were loose, a link in the chain being filed through with a piece of window glass, which was found concealed in his bed. While this was being adjusted, he glared savagely and, in a jocose manner, said it had been so for a month past."

With this last hope of escape gone, Tom seemed to change his mind about the confession everyone was nagging him to make. He called for Captain Richard Allison, one of Vance's assistants on the defence team, and handed him a short pencil-written note, its letters scratched together in Tom's own crude, unskilled hand. Tom made Allison swear not to let anyone see the note until after the execution. "Statement of Thomas C. Dula," it read. "I declare that I am the only person that had any hand in the murder of Laura Foster. April 30, 1868."

Tom also gave Allison a 15-page statement exhorting young men to lead a more virtuous life than he'd managed himself, but which did not mention Laura's murder. "There was nothing remarkable in this document," the Herald's man reports.

Nothing remarkable in its content, perhaps, but if the Herald's right in suggesting Tom wrote those 15 pages himself, they become the best evidence we have that he was literate when he died. It's equally possible though, that Tom dictated the long statement to Allison, and that it's only a bit of loose wording on the Herald's part that hints otherwise.

"All indications had been up to that time that Tom Dula was illiterate, although he did attend school as a child for three months," Foster West writes. "He had signed his Pledge of Allegiance when leaving military prison with his mark, an X with the signature of a witness beside it. [But] there is a remote possibility that Tom, during his long two years of incarceration, had learned to write in a crude manner."

If Tom was illiterate, it's one more nail in the coffin of rumours that he was responsible for writing his own ballad, and treated the crowds to a performance of it as his cart rolled towards the scaffold. Even if you assume he could write, though, you've still got to explain how the Herald's reporter could have watched Tom doing this, and yet never thought it worth mentioning in his long and detailed account. You've only got to read the Herald's story to see its man was determined to report every bit of colour he could find on the day, and to think he'd omit an episode like that is inconceivable.

Left alone in his cell overnight and now with just hours to live, Tom lost the composure he'd maintained for so long. He spent the night pacing up and down as far as his leg chain would allow, and managed to grab only the odd half hour of fitful sleep. He'd refused to see any clergymen throughout all his time in jail, but all that changed as his hanging day dawned. "After breakfast, he sent for his spiritual advisers and seemed for the first time to make an attempt to pray," the Herald tells us. "But still, to them and to all others, denied his guilt or any knowledge of the murder. The theory seemed to be that he would show the people he could die game."

Later that morning, Tom allowed the Methodist minister he'd been given to baptise him, and then dropped to his knees in fervent prayer. "When left alone [he] was heard speaking incoherently, words occasionally dropping from his lips in relation to the murder," the Herald says. "But nothing was intelligible. Thus wore away the last hours of the condemned."

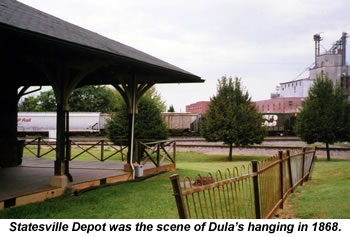

Because Tom's trials had been dragging on so long, and because people from at least three different counties had been involved, news of his hanging spread throughout the region, drawing a large crowd to Statesville as spectators. I can't improve on the Herald's vivid description of the day's events, so I'm simply going to reproduce some long extracts from it here:

"By eleven o'clock, AM, dense crowds of people thronged the streets, the great number of females being somewhat extraordinary. [...] A certain class, indicated by a bronzed complexion, rustic attire, a quid of tobacco in their mouths, and a certain mountaineer look, were evidently attracted by the morbid curiosity to see an execution, so general among the ignorant classes of society.

"The preliminaries were all arranged by Sheriff Wasson. A gallows constructed of native pine, erected near the railway depot in an old field - as there is no public place of execution in Statesville - was the place selected for the final tragedy. A guard had been summoned to keep back the crowd and enforce the terrible death penalty, and for the better preservation of order, the bar rooms were closed." (3)

Rather than the "white oak tree" mentioned in Tom's ballad, Statesville had built him a simple gallows from two upright poles, set about ten feet apart, with a crossbar linking them at the top. The crossbar was placed high enough to let the cart they planned to use for Tom's transport draw up directly beneath it, leaving him to dangle there when the cart pulled away again.

The Herald's man must have been moving through the crowds at this point, stopping to quickly interview any spectators who looked promising and jotting down their replies as he went. He was obviously struck by the unusual number of women in the crowd - far more than he seemed to expect at a hanging - and mentions this several times in his report. He puts the crowd at nearly 3,000 people of Tom's "own race and colour", but makes no attempt to estimate the number of black people also attending.

We have other eyewitness accounts of Tom's hanging too, the best of which comes from a man called Hub Yount, whose father and aunt were both present. Yount, whose family then lived in nearby Catawba County, passed on his father's account to Gardner, who reproduces it in his book. "Thousands and thousands of people gathered to see the execution," Yount writes. "Statesville was a small town then, and [there were] many fist and skull fights, old enemies meeting. There were several gun battles on the streets that day." (12)

It's while patrolling this lively crowd that the Herald's man met Tom's former army companions, noting their "anxious and singular curiosity" to see how their old comrade would die. "They believed him guilty, without a confession, and none sympathised with him," He wrote.

Tom was led out of the jail just before quarter to one, and once again, the Herald's man was there to watch:

"With a smile upon his features, [the condemned man] took his seat in the cart, in which was also his coffin, beside his brother in law. The procession moved slowly through the streets accompanied by large crowds, male and female, whites and blacks, many being in carriages and many on horseback and on foot.

"While on his way to the gallows, he looked cheerful and spoke continually to his sister of the Scriptures, assuring her he had repented and that his peace was made with God. At the gallows, throngs of people were already assembled, the number of females being almost equal to that of the males. The few trees in the field were crowded with men and boys, and under every shade that was present, were huddled together every imaginable specimen of humanity."

As the procession came within sight of the gallows, official horsemen rode fast into the field to disperse the crowds. This cleared the way for Tom's cart, which halted under the gallows' frame at eight minutes past one. Told by Sheriff Wasson he could address the crowd if he wished, Tom stood up in the cart, the noose already round his neck, and spoke in what the Herald calls "a loud voice that rang back from the woods".

He spoke for nearly an hour, discussing his early childhood, his parents, his time in the army and the secessionist politics that still bedevilled his home state. He accused several witnesses at his trial of telling lies against him - reserving particular ire for James Isbell - and said it was only those lies which had put him on the scaffold today. His written confession, remember, was still a secret between himself and Allison, who'd sworn not to make it public till Tom was dead.

He spoke for nearly an hour, discussing his early childhood, his parents, his time in the army and the secessionist politics that still bedevilled his home state. He accused several witnesses at his trial of telling lies against him - reserving particular ire for James Isbell - and said it was only those lies which had put him on the scaffold today. His written confession, remember, was still a secret between himself and Allison, who'd sworn not to make it public till Tom was dead.

"The sheriff allowed Tom Dooley to make a long talk," Yount confirms. "And, at the conclusion, an old white-bearded man pointed at Dooley and repeated the song that had been sung many times for the six months prior. I don't remember the words, except the old man pointed and sang: 'Oh Tom Dooley, hang down your head and cry. Because you killed poor Laura Foster and now you must die'."

I doubt Yount's got those words exactly right, because they're impossible to scan to the tune we know was already used. They're certainly close enough to confirm Sutton's dating of something very like this chorus at 1867, though, and that's quite useful in itself.

Concluding his speech, Tom bade an affectionate farewell to Elisa, who was taken off the cart, and then watched as the rope dangling round his neck was thrown over the gallows' cross beam and fastened. The cart was then drawn away, leaving Tom to hang. Here's the Herald again:

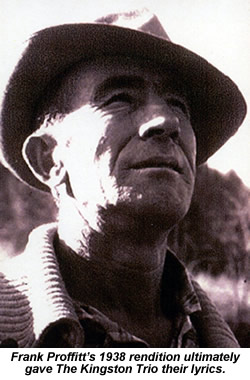

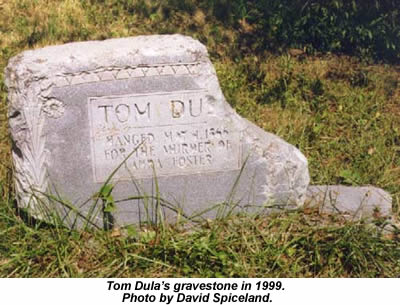

"The fall was about two feet, and the neck was not broken. He breathed about five minutes, and did not struggle, the pulse beating for ten minutes, and in 13 minutes life was declared extinct by Dr Campbell, attending surgeon.