The local audience who first read Land's verses would have known full well that Tom was the groom he had in mind, and been equally sure that his "vile guest" must be Ann. Throughout the poem, Land shows the pair acting together in Laura's murder and disposal, using plural phrases like "those who did poor Laura kill", "they her conceal" and "to dig the grave they now proceed". By doing this, he ensures that Ann is thoroughly implicated in the whole rotten business.

The local audience who first read Land's verses would have known full well that Tom was the groom he had in mind, and been equally sure that his "vile guest" must be Ann. Throughout the poem, Land shows the pair acting together in Laura's murder and disposal, using plural phrases like "those who did poor Laura kill", "they her conceal" and "to dig the grave they now proceed". By doing this, he ensures that Ann is thoroughly implicated in the whole rotten business.

Laura herself is depicted as a sweet, innocent girl, too full of childlike love to imagine Tom could ever wish her harm:

"Her youthful heart no sorrow knew,

She fancied all mankind were true,

And thus she gaily passed along,

Humming at times a favourite song."

Happy Valley's residents would have known that the real Laura was a good deal raunchier than that, but swallowed the lie for the extra narrative satisfaction it offered. The more of a saint Laura could appear, the more villainous Tom and Ann looked by comparison, and that's what delivered the story's disreputable thrill.

Land takes us - somewhat laboriously - through the various stages of Laura's discovery, then closes with a bit of tidy alliteration and one last pious thought to ensure we don't have nightmares:

"The jury made the verdict plain,

Which was, poor Laura had been slain,

Some ruthless fiend had struck the blow,

Which laid poor luckless Laura low.

"Then in a church yard her they lay,

No more to rise till Judgement Day,

Then, robed in white, we trust she'll rise,

To meet her Saviour in the skies."

Land's poem, which he called The Murder of Laura Foster, was written to be read rather than sung, but I have heard one musical setting of it. This appears on Sheila Clark's 1986 album The Legend of Tom Dula and Other Folk Ballads, where Clarke gives us a lovely a capella rendition of Land's full 21 verses, with nothing but a short fiddle phrase to divide each of its three sections. She negotiates the more awkward lines with admirable style, and it's a tribute to the sweetness of her voice that the track's nine minutes and fifteen seconds passes so pleasantly.

Formal legal proceedings against Tom and Ann began on October 1, 1866, when North Carolina's superior court met at Wilkesboro under Judge Ralph Buxton. The charges they made against Tom said he "feloniously, wilfully and of malice aforethought did kill and murder [Laura Foster] against the peace and dignity of the state". Ann was charged that she "did stir up, move and abet, and cause and procure, the said Thomas Dula to commit the said felony and murder," and then chose to "receive, harbour, maintain, relieve, comfort and assist" him.

In other words, Tom was accused of killing Laura, and Ann was charged with both encouraging him to commit the crime and harbouring him afterwards. The prosecution quickly agreed to drop Ann's harbouring charges, leaving just the first accusation against her.

Tom and Ann were brought to the courthouse so they could hear the indictments read against them, and then both returned to Wilkesboro jail to wait for trial. Dr George Carter, James Melton, Wilson Foster, Lotty Foster, Jack Adkins, Ben Ferguson, Pauline Foster and Betsy Scott were all among the witnesses who'd be called.

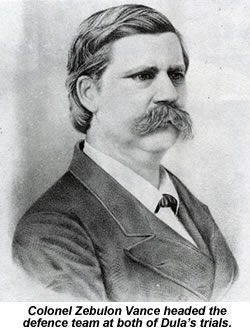

It's still not clear how Tom managed to recruit Colonel Zebulon Vance to defend him, but it certainly represented a bit of coup. Vance came from a military family, and had been elected to Congress twice before the Civil War cut his second term short. He commanded the 26th Regiment of North Carolina's Infantry in battle for a while - not the 42nd where Tom served - and then spent the remainder of the war serving two terms as state Governor. He was arrested by the victorious Federalist forces in May 1865, spent two months in their jail, and returned to freedom an almost penniless man. He began his Charlotte law practice in March 1866, the same month Tom discovered he'd contracted syphilis.

We've got the court's confirmation that Tom was insolvent just three weeks after his indictment was read, so he was clearly in no position to pay Vance for his services. Whether that means Vance was paid by the state, or whether he conducted the defence for free, I don't know. More intriguing is why he agreed to take the job on at all.(5.5)

As we've seen, the rumours that Vance agreed to defend Tom because the two men had served together - or even because he'd enjoyed Tom's fiddle playing round the campfire - do not stand up to the scrutiny of Tom's military records. Gardner says it was Colonel James Horton, one of Tom's many cousins in the area, who asked Vance to get involved, but that seems a pretty flimsy motivation on its own.

As a Congressman, Vance had been against North Carolina's secession, and stood on a Conservative ticket against the Confederacy's man. No doubt he had a certain amount of sympathy for any Confederate soldier down on his luck, but we can dismiss the notion that he was a rabid Johnny Reb, determined to defend any secessionist veteran for that reason alone. That's not to say, however, that Civil War politics were completely irrelevant to his decision.

"North Carolina was 'occupied' by a federal army during the first trial," Foster West points out. "Members of the prosecution were also Republican 'conquerors'. Members of the defence were Democrats and losers of the war. [...] It is interesting to note that all the members of the defence in Tom Dula's first trial had been officers in the Confederate Army, whereas none of the members of the prosecution had served in the military during the war." You couldn't ask for a clearer dividing line that that.

Tom's Wilkesboro trial began on October 4, and Vance got the ball rolling by arguing that feelings against Tom and Ann were running so high in Wilkes County that a change of venue was required. "The Public mind has been so prejudiced against them to such an extent [in Wilkes] that an impartial and unbiased jury could not be obtained," he told Judge Buxton.

The court agreed, and arranged for the trial to be moved across the Iredell County line to Statesville, about 30 miles away. Vance had lost Wilkes County in his most recent Governor's race, but won the vote in Iredell, so this move was good news for the way a Statesville jury might view Dula's attorney too.

A week later, Sheriff Hix moved Tom and Ann to Statesville jail, a old building on Broad Street with a pillory, whipping post and stocks out front. Iredell's county sheriff was concerned this jail might not be secure enough to hold Tom, so the county agreed to pay for eight extra guards to be stationed there during his stay. That would have been a considerable expense, and the fact that Iredell's authorities were prepared to bear it is one more bit of evidence that they considered Tom a very dangerous man.

The Statesville proceedings began on October 15, 1866, again with Judge Buxton presiding. He had a reputation as a cautious but meticulous man, careful in his interpretation of the law, and anxious to be accurate in his rulings. Twelve jurors were selected from panel of 100 Iredell County freeholders - all men - and Vance stood up to speak once again.