It's February 29, 1964 in Santa Monica, and Bob Dylan is in his dressing room at the Civic Auditorium waiting for a telegram. But who's that teenage kid delivering it?

It's February 29, 1964 in Santa Monica, and Bob Dylan is in his dressing room at the Civic Auditorium waiting for a telegram. But who's that teenage kid delivering it?

"I actually got to meet Dylan as a kid," Tom Russell recalls. "I pretended I was the telegram messenger. Later, in the parking lot, Dylan asked me where the nearest liquor store was.

"My friends and I didn't know, but we told them to follow our car. Finally, at a stop light, he got out and danced around our car, laughing and waving his arms like a whirling dervish. Then he ran back to his car and they drove off. Into history."

Russell's one of those people who seem to have crammed four or five lifetimes into his stay on Earth, and this weird encounter with Dylan was just the beginning. Fascinated by the Tex Ritter and Marty Robbins cowboy ballads he heard on the radio as a child, Russell had already taught himself a few chords on his older brother's guitar and begun to fool around with the idea of writing his own songs. But it was not till he snuck into a second Bob Dylan show the following year that those ambitions snapped into focus.

This time, the venue was LA's Hollywood Bowl. "When he sang Desolation Row, it really resonated with me that he'd suddenly pushed the song format forward," Russell says. "I didn't know what the song meant - I'm still trying to figure that out - but I think it was then that I thought, 'That'd be the greatest job to do'. But I didn't have the guts to pursue that for another five or six years."

Instead, he got himself a criminology degree and set off for a year of academic field work in Nigeria. Russell was then just 20 years old, and the Biafran War was at its murderous height. He quickly got used to having drunken soldiers pointing their machine guns at him, and once managed to bribe his way out of a tricky situation by offering up a fresh pineapple. At night, he'd head for Ibadan's highlife clubs, where one night he found himself jamming with King Sunny Adé.

"I was bored with academia, so I used to go down to the bars at night with my old Martin guitar. I'd sit in the back of the bar playing along. Mostly, it was groove music - these guys would play a song for an hour sometimes. Sunny came up to me one time and said, 'Play along with this one'. I remember a couple of nights playing behind them. I would sit out in the audience playing, and they would all say, 'Wow, look at the white kid'. It was cool."

He spent the next decade playing his own band gigs in some of Vancouver's worst bars, often having to face down an audience that was both horrendously drunk and determined to sling bottles at the stage. He'd won a couple of songwriting contests by this time, but otherwise his music career seemed to be going nowhere. By 1981, he was making ends meet by driving a cab in New York - and that's when everything changed.

It's August 29, 1965 in Los Angeles, and The Beatles are just arriving at The Hollywood Bowl for the first of two sold-out concerts there. But who's that teenage kid getting in the way of their car?

"I'd snuck in posing as a security guard," Russell recalls. "I jumped in front of their limo right when they pulled into the Hollywood Bowl and I just started screaming orders at everybody. The gates opened magically and I took them right to the edge of the stage, then opened the limo door. In my mind, Lennon said something like, 'Couldn't have done it without you, mate!'.

His first great song was Gallo del Cielo. Written in 1979, it tells the story of a formidable fighting rooster and the desperate Mexican lad who wagers everything on its prowess. Like much of Russell's best work, it's a condensed short story, driven along by the Spanish guitars, stuttering accordions and yelping, impassioned vocals he'd heard leaking across the border in his youth.

"I think the song El Paso by Marty Robbins was a turning point in popular song history," he says. "It was a huge hit in 1959, and what an astounding piece of writing. That probably influenced Gallo del Cielo a bit: it's another long story song. And I like the terrain. I grew up near the border in California back in the days when everybody - movie stars too - went to Tijuana on the weekends for gambling, horse races, bullfights, bars, whatever. I grew up in that culture and that border music scene."

Armed with his new song, Russell took a month off cab driving to sing Johnny Cash covers in a Puerto Rican carnival. Once in a while, he'd slip Gallo del Cielo into the set and always found it went over big with the show's mostly Hispanic crowd. One Puerto Rican worker at the carnival grew so invested in the song that he shot Russell's guitar in protest at the tale's unhappy ending.

Then it was back to cab work. One night in 1981, Russell picked up a midnight fare in Queens and realised it was The Grateful Dead's Robert Hunter. They got talking, Russell mentioned he was a songwriter and Hunter asked him to sing one of his compositions there and then. Russell gave him an a capella version of Gallo del Cielo, and Hunter liked it enough to insist they drive 15 miles back the other way to fetch a demo tape of the song from Russell's apartment. Hunter promised he's pass the tape along to both the Dead and to New Riders of the Purple Sage, with a view to one or other band covering the song.

Neither took him up on it, but Hunter followed through anyway. "Two weeks after the ride, he got me up on stage to sing Gallo del Cielo at The Bottom Line, and that yanked me back into the music business," Russell says. "Then I opened for him - we did a few shows at the old Lone Star Café - and it changed my life. Here's a guy who really put it on the line for a taxi driver, you know? It was a life-changing experience."

Russell's been working full-time in what he calls "the song trade" ever since, and now has 35 albums to his credit. Both Springsteen and Dylan have praised his songwriting chops, and he's had songs covered by everyone from Johnny Cash and KD Lang to Ian Siegel, Joe Ely and Nanci Griffith. Once you've got a celestial rooster in your corner, it seems, the battle's half won.

It's May 6, 1989 at the Zug Festival in Switzerland, and Johnny Cash is playing to a crowd of 10,000. But who's that middle-aged man he's calling up to join him on stage?

"He got me up out of the audience for an encore of Peace in the Valley because he knew my songs Blue Wing and Veteran's Day," Russell recalls. "He had me stand next to him in front of all these people, and when it came to the last verse he said, 'Take it, Tom'. I'd had a few beers, and I was sweating because I didn't know the last verse - lions and lambs and all that. So he sang it in my ear, and it came out of my mouth sounding like I was Johnny Cash's ventriloquist dummy."

Russell's new album, Folk Hotel (see below) has a couple of surprises up its sleeve. His trademark Tex-Mex sound appears on only a handful of tracks, replaced elsewhere by a back-to-basics folk treatment. Not only that, but on the album's second track, Leaving El Paso, we learn that Russell has sold his home of 20 years on the Rio Grande to relocate 300 miles north in Santa Fe. His songs of the past two decades have been so rooted in El Paso's myths and musical heritage that it seems unthinkable he should no longer be living there.

"I really mined that part of the country," he admits. "I was always drawn thematically to all the deep history of the border. In 1997, I moved there from New York. I bought a vintage adobe and a few acres where I farmed pecan trees - irrigated my property right off the Rio Grande. I loved thinking I was a farmer, and I went to Juarez, to the bars across the border. All that was destroyed with the drug wars about ten years ago. People started dying by the thousand over there.

"It didn't seep across the border much, because the drug lords weren't stupid enough to kill the goose that laid the golden egg, but the vibe went away. El Paso became very crowded, and the land around our farm became suburbia. We needed a change."

Talk of the border brings us neatly to another of Russell's most memorable songs. Who's Gonna Build Your Wall? was released in 2006, when George W. Bush was still president, but now it's impossible to hear it without thinking of Trump. "Who's gonna build your wall, boys?" it asks. "Who's gonna mow your lawn? Who's gonna cook your Mexican food when your Mexican maid is gone?" I asked Russell what he made of the new life this song's taken on in the past couple of years.

"I wrote the song about a developer in San Diego I'd heard about who used illegal labour to keep the illegals out. I thought it was funny. It's taken on its own meaning now and I still do it occasionally on stage. But I kind of stress the funny nature of it.

"We've been across America recently on tour, and the country I encounter is not the same America the news is feeding out. Trump exists, all that exists, but there's still an America out there that doesn't have anything to do with the news. It has to do with real people, and that's mostly what I'm interested in."

These are just the people he portrays in Harlan Clancy, one of the new album's stand-out songs. "He's a combination of many people I worked with when I did odd jobs back in the day. He's a guy without a college education, who gets up and goes to work every day. I think Europeans - and a lot of Americans - don't know this guy. They go to New York or they go to Vegas, but I don't think they've ever been to Southern Ohio.

"We go through there all the time and I know some really good people out there, but they're different-type people. They're not college-educated. They don't talk politics all day. They go to work, they eat, they drink, they try to do good. In that song, I'm just trying to get to the heart of a common guy."

And the new sound? "I did two records this year, back-to-back. I did the Ian & Sylvia tribute because they were strong heroes of mine, and I learned a lot from them. That was a very simple record: two guitars and a female voice in harmony [with mine]. It was almost like starting over. I was rethinking folk music via what my idols did and then going forward with my own record. I started looking back to find out what lured me into this business in the first place and find the heart of that. As a music fan, I wanted to recreate the sound that got me into this thing.

"I think the story song is a lost art in a lot of ways. I don't think it's a popular format these days among younger people, but I was always drawn to the story, whether it was in a Broadway musical or a cowboy song. Always the story song."

An edited version of this piece appeared in fRoots 415/416 (the Jan/Feb 2018 issue). You'll find some bonus extracts from our conversation below, but first here's my fRoots 413 review of Russell's latest album.

Tom Russell: Folk Hotel.

Tom Russell: Folk Hotel.

What we have here is another good, solid album of immaculately-crafted songs from one of America's greatest troubadour poets.

The record's tone of gruff nostalgia is set straight away by opening track Up In The Old Hotel, which hymns New York's Chelsea hotel in its bohemian heyday of the 1950s and 1960s. As in so many of this record's songs, Russell has dead writers he wants to salute - in this case Dylan Thomas and The New Yorker's Joseph Mitchell - and a wistful memory of better times to convey.

Thomas pops up again in a mournfully tender song called The Sparrow of Swansea. Leaving El Paso gives us Russell's farewell to a much-loved home town, while both Harlan Clancy and I'll Never Leave These Old Horses celebrate the old-fashioned, hard-working decency of a generation that's now almost gone. The latter is a tribute to Ian Tyson.

Musically, the focus is always on Russell's voice, his slow-picked acoustic guitar and the tale itself. There are plenty of other musicians on the album - including Eliza Gilkyson and Joe Ely - but their contributions are always carefully restrained, limiting themselves to a little careful colouring at the song's edge. The Tex-Mex flavour dominating some earlier Russell albums is less in evidence here, showing through on only two or three of the 13 tracks.

Best of all are two of the album's sprightlier numbers, both driven along by Max De Bernardi's fine guitar work. Rise Again, Handsome Johnny describes JFK's assassination and wishes he could return to us today. It's a perfect bookend song for Steve Earle's Christmas in Washington.

Scars on his Ankles - one of two bonus tracks you'll miss if you choose to stream or download the album - is even better. It relates the journalist Grover Lewis's drunken encounter with Lightnin' Hopkins in 1960s Texas. Russell's throaty spoken-word narration, backed by a solo bluesy guitar, lets you smell the sweat on Hopkins' skin and the "head tearing-up" bourbon tainting his breath. It's great stuff.

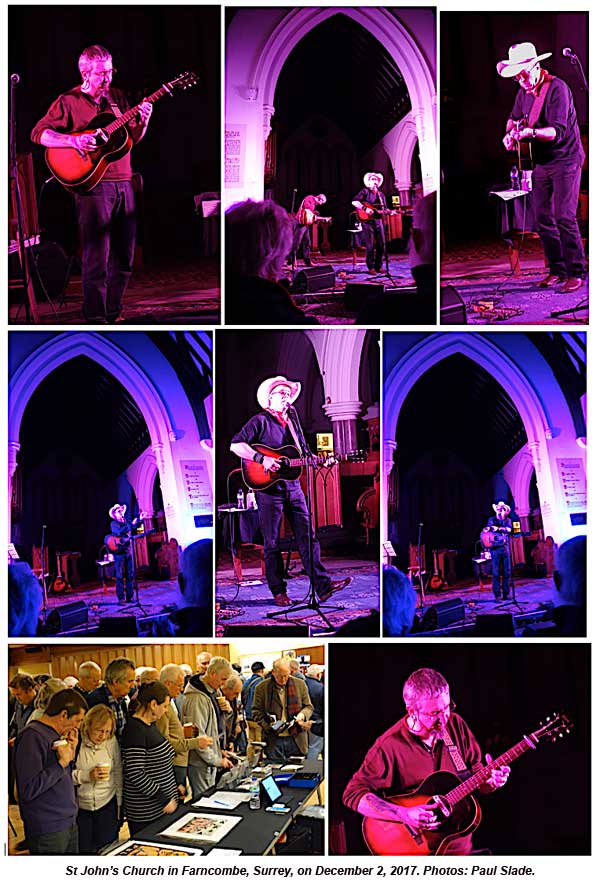

2017's UK gigs: Notes from the second row

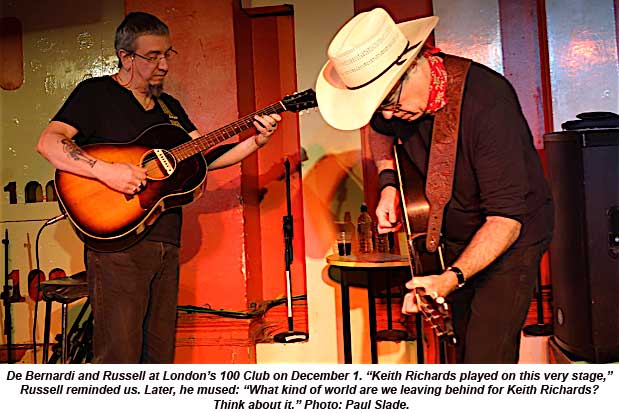

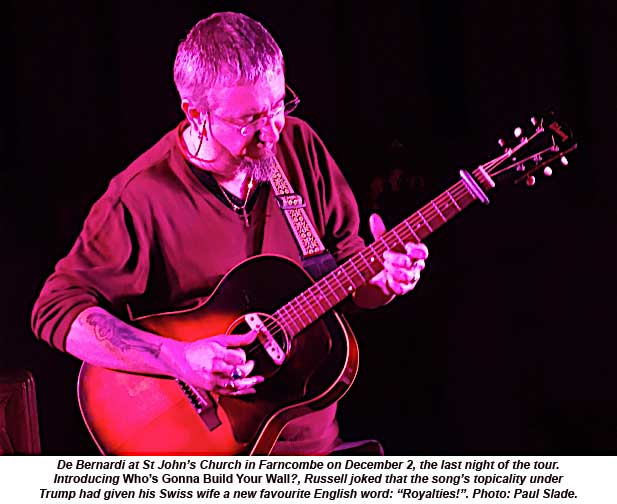

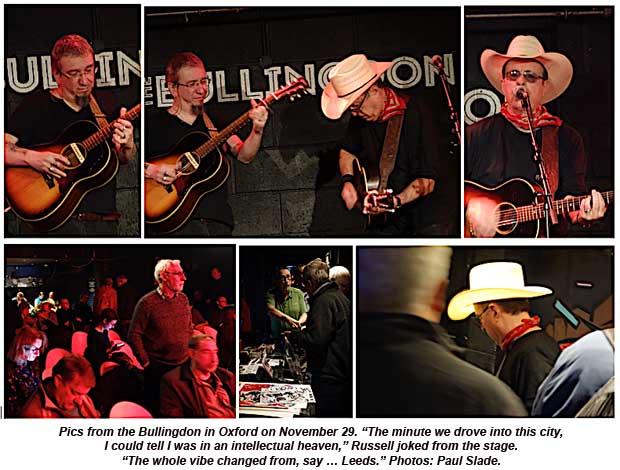

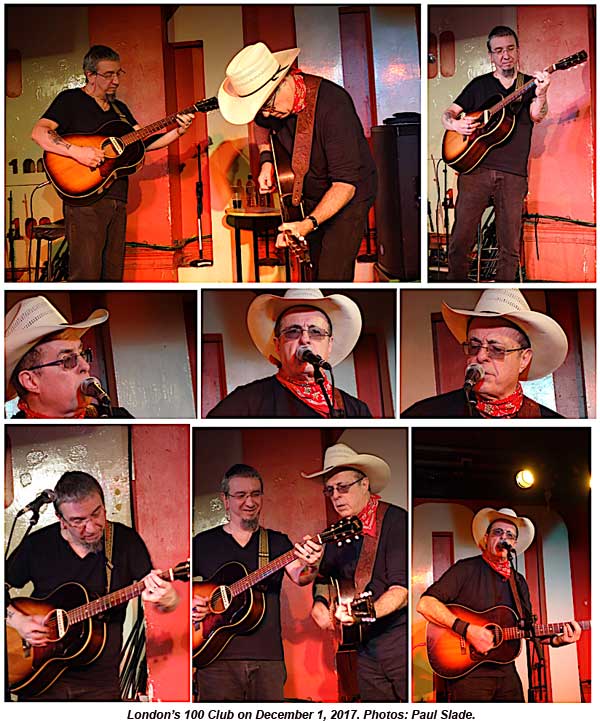

I managed to catch the three final three gigs of Russell's 2017 UK tour, watching him play live at an Oxford pub called the Bullingdon, the 100 Club in London and St John's Church at Farncombe in Surrey.

I was too busy enjoying myself to take notes while any of the gigs were going on, but I did sit down for an hour after each one to jot down a few random memories before going to bed. I've now boiled those jottings down to the 15 bullet points below, which I hope will give you some idea of what a splendid four days it was.

1) Russell opened all three gigs in his alias as Spanish Frankie, "the world's cheapest support act". Frankie's job was to let Russell warm up his fingers with a medley of road song fragments from the songwriters he most admires. Ian Tyson, Guy Clark, Bob Dylan, Leon Payne, Townes Van Zandt and Leonard Cohen all featured in this slot.

2) At Oxford, we got to hear a little more about the sideshow acts Russell and his band backed during their 1970s stint playing in Vancouver's sleaziest bars. Chief among these was the stripper Big Jimmy, a 300lb female impersonator, whose grand finale revealed a "Do Not Enter" traffic sign tattooed on his ass.

3) De Bernardi, did a number of his own every night, drawing on his wide repertoire of blues classics. In Oxford it was Blind Blake's Wabash Rag, at the 100 Club we got the same man's Too Tight and at the Farncombe church gig, it was a gospel song with the chorus "who's gonna save poor me?" During these numbers, Russell would either strum along or simply stand back and admire De Bernardi's picking.

4) Every now and again at all three gigs, Russell would break away from his own material to challenge the audience. "Tell me who wrote this one," he'd say before playing a snatch of someone else's song: Lost Highway got this treatment, as did Pancho & Lefty, LA Freeway, Splendid Isolation and El Paso. He never got more than a few words into the first line before someone in the audience shouted out the correct answer. Meanwhile, I'd have realised it was a familiar song, but still be trying to dredge up the writer's name.

5) The songs he played at all three gigs included: Up In The Old Hotel; Guadalupe; Leaving El Paso; Stealing Electricity; Rise Again, Handsome Johnny; Tonight We Ride; St Olav's Gate; Blue Wing; Who's Gonna Build Your Wall and Navajo Rug.

6) PlanetSlade's ears pricked up every night when we came to Handsome Johnny, which Russell described as his stab at writing "a classic murder ballad like Stagger Lee". This number was always a showcase for De Bernardi, who used it to demonstrate his Mississippi John Hurt chops to great effect.

7) Leaving aside Spanish Frankie's road song fragments and the "test the audience" snippets I mentioned earlier, we also got covers of Michael Smith's The Dutchman at Oxford and a storming Johnny Cash medley at the 100 Club. Russell ran Cash's Folsom Prison Blues, Big River, I Walk The Line and Cocaine Blues together into a medley, growling the lyrics out in Cash's deep voice, while De Bernardi channelled Luther Perkins behind him.

8) The evening's first set always closed with Tonight We Ride, and the second with Navajo Rug. These - along with Who's Gonna Build Your Wall? - were the only songs where Russell had any success in persuading we repressed English punters to sing along with a bit of gusto. Nothing personal, Tom: it's just not something we're good at in this country.

9) Perhaps the most irritating audience member at any of the three gigs was the bloke at the back of the 100 Club who insisted on roaring "Go on, Tom!" at the outset of every single number in the second set. Russell reassured him several times that going on was precisely what he planned to do, but it had no effect. "Go on, Tom!" he'd roar again.

10) Other Russell songs which got at least one or two outings over the three gigs included: He Wasn't A Bad Kid, When He Was Sober; Finding You; Sparrow of Swansea; Love Abides; Angel of Lyon; Nina Simone; Canadian Whisky; California Snow; Veteran's Day; East of Woodstock, West of Vietnam; I'll Never Leave These Old Horses; The Last Time I Saw Hank; The Light Behind the Coyote Fence and Hair Trigger Heart.

11) Who's Gonna Build Your Wall? got a big response at all three gigs, with Russell mocking politicians by wobbling his jowls and flashing a Nixonesque double V sign. "It's gonna be great!" he'd declare as he introduced the song. "We're gonna build a wall round Oxford/London/Farncombe. It'll be great!"

12) Russell got requests for his song When Sinatra Played Juarez at two of the three gigs I saw. Unfortunately, he couldn't remember it, managing just one line in London and only the opening verse in Farncombe. Still, with what must now be over three hundred songs to his credit, you can hardly blame him for not instantly remembering them all.

13) At Farncombe, Russell recalled a 1969 evening in Nigeria, watching cinema newsreel footage reporting that man had just walked on the moon. The Yoruba tribesman filling the cinema were so scornful of this claim that they started hurling their beer bottles at Neil Armstrong's image onscreen. Russell got swept up in the moment, figured they must be right, and slung his own bottle at Armstrong too.

14) The newsreel incident is mentioned - at least obliquely - in East of Woodstock, West of Vietnam. "In the cinema, I saw the man on the moon," Russell sings. "I laughed so hard I cried."

15) Much as I would have liked to hear Gallo del Cielo at one of the three gigs, I kind of admire Russell's refusal to treat it as a song that absolutely has to be trotted out every single time he appears. Nothing destroys a song quicker than that kind of obligatory rote performance, so I think he's wise not to overwork the fighting rooster's tale. This way, if I ever do get to hear him sing it live, I'll know I'm witnessing something a bit special.

Tom Russell interview - bonus material

There was a lot of good material from my hour's conversation with Russell which I couldn't make room for in the fRoots piece above, so I'm using it here instead. Sit back, get comfortable, and read what else he had to say.

. on Folk Hotel.

Tom Russell: "There's some poetry there, a lot of Celtic-sounding stuff which I've been into lately, and there's Harlan Clancy, which kind of speaks to the common American now without making any judgement on him. Then there's a long thing about Lightnin' Hopkins [Scars on his Ankles], where I tried to blend music journalism with a biographical piece about Lightnin'. I think if there was any thematic thing, it was to try and give a nod back to the Celtic storytelling tradition, maybe."

PlanetSlade: It's a very economical album: focused very tightly on just your voice, your guitar and the story you're telling.

TR: "That's what I wanted to do, because - not to brag - but I think I'm singing better than ever [and] I'm playing better guitar. After doing a bunch of solo gigs, I was a lot more confident, and I'd gotten tired of being in the studio where you piece songs together. That, to me, just loses the core of what you're trying to do. I started with myself on the guitar and the vocal and got a reading of the song that I liked then added a few things.

"I'm playing a lot of the instruments on the record, like some of the harmonica, a little bit of electric guitar and some of the harmonies, and then Mark Hallman filled in on a lot of stuff. Joel Guzman, the great Tex-Mex accordion player, played on a few, including Dylan's Tom Thumb's Blues. Joe Ely sang that with me, and Eliza Gilkyson sat in on a few. But I kept it very rootsy, very basic, just to get back to see how I could start over and rethink the recording process and the storytelling process. I wasn't able to do that till now.

"I'm going to take it a little bit further with the next record. I may re-explore country music with the next one, so there'll have to be telecasters and steel guitars etc, but I wanted to start here. That's two years away, but I'm thinking of giving a nod to my country roots in the 50s and 60s and having, on some songs, a Bakersfield type sound - before country music went to hell and became pop music."

. on De Bernardi.

TR: "I think readers of fRoots will really dig Max, because he plays a lot of traditional finger-picking stuff. [Duo shows are] as far as I go these days. I'm heading more towards the solo thing because we're selling out most venues anyway. I love working with a good guitar player, but solo allows me to extend myself more from the storytelling [point of view] and work on my guitar playing."

PS: How do you enjoy touring these days? Does it get to be a chore being away from home for so long, or do you still find things to enjoy in the process?

TR: "We love it. We stay in good hotels, which is important, we eat good food. As I think Dick Gaughan said, 'We're not getting paid for being on stage, because we love that. We're getting paid for being in a car for eight hours and sleeping in a bad bed.' We've eliminated a lot of that stuff by touring intelligent distances, staying in good hotels, eating good food. My wife Nadine, who took over managing me a few years ago, turns down more gigs than we take.

"Unlike some Americans, I don't try to overwork the UK. It's such a wonderful market. I mean, there's probably 100 gigs I could do there in these great small folk clubs, theatres. But I try not to overdo it: I try to hit the UK and Ireland every two years when I have something new to say."

PS: Have you played the 100 Club before?

TR: "Last time we were in London, we sold out there. The Kinks played there, the Stones played there, you've got that vibe in the walls, you know? It also helps that there's a bar there - that's important, I think. I love playing a theatre that holds 200 or 150, or a club that holds 200, because I like being close to the audience. A 200-seat club where you've got people two feet in front of you who you can talk to and relate to is better for me. And you take more money out of a place like that, because they don't have so many cuts. They don't take the merchandise money and all this."

PS: I read in one of your old interviews that you find audiences over here are more knowledgeable about roots music than they are in the US. Is that true?

TR: "Yes - that's a good point. If I stand up there and start talking about Gram Parsons or Steve Young or Ewan MacColl or Townes van Zandt, everybody's with me in the UK and Ireland. I mean, you just get people staring at you in the US. Everything they know, the same as politics, comes from the media, and the media is very poor these days in the States. You don't have that intensity that you get over there [in the UK and Ireland], with an intelligent understanding of roots music. It's a far more vital, rootsy scene there.

"I think the press is a lot hipper in the UK and Ireland than it is here now. Your calibre of writing over there, not only in the daily press, but Mojo, Uncut, fRoots, various country magazines, I think it's stellar. The writing is very good and the people still seem to care about music, film, art, books. I've leaned a lot about what books I might want to buy or what films I want to see by reading Mojo, Uncut and fRoots."

. on his worst gig ever.

PS: Again, going through your old interviews, I was reading about a particularly godawful 1970s gig you played in Canada's frozen north. Tell me that story.

TR: "It was Halloween night, it was freezing, everybody in the audience was drunk and throwing things at the stage. One of those nights, you know? There were so many gigs like that back then when I worked topless bars. Usually, those things happen when you're filling in for another band and the regulars show up and harass you. I saw that for ten years in my early days.

"As a sociologist and a criminologist, of course, it's fascinating. I thought, 'It's colourful if you survive it', but I also knew I was going to get out of there if I kept at it."

. on moving from El Paso to Santa Fe.

PS: I was surprised to see you've moved away from El Paso. It's probably fair to say your music's been more associated with the border lands culture round there than any other place, isn't it?

TR: "I would guess so - specially in the last 20 years. The Rose of Roscrae wasn't specifically a border record, but it was a western-themed record, and it did have some Mexican music on it. Yeah, Borderland, the record I did with Calexico [Blood & Candle Smoke], they all have that feel because they have a horn section. I mean, I lived in New York from 1980 to 1997, but I wasn't a true New Yorker. There wasn't that much I could mine out of there."

PS: So what prompted the move? Was it increasing development in El Paso - or danger from the drug wars across the border, perhaps?

TR: "Both. I went to Juarez a few times in the early 2000s before I met my wife. We were pretty close to gunfire, my friends and I, inadvertently in the wrong part of town. The funny part is, at the height of the drug war, ten or twelve years ago, Juarez was the most dangerous city in the world, but El Paso, a quarter mile across the river, was one of the safest cities in the US.

"It wasn't dangerous per se in El Paso, it's just that that rural ambience kind of faded. It's been a boom city the last ten years, two or three hundred thousand people have moved there, and I didn't like the suburban vibe. My wife's a runner, and you can't run any more because there's too many loose pit bulls out there. In that sense, it was a little dangerous, you know?"

"It was time to move on, so Nadine and I looked at options up the Rio Grande. As I say in the song [Leaving El Paso], we followed the same trail the Spanish took 500 years ago. They called it the Jornado del Muerto: The Journey of Death. If you follow the river up from El Paso, five hours in a car, you end up in Santa Fe, which we found quite beautiful - though we live about 20, 30 minutes outside of town, a little isolated in the desert. It's beautiful. We're only here part-time, but we built me a painting studio, a writing studio, a little tequila bar where I have all my memorabilia on the wall. It's fun, and the views out the window are astounding.

"We also live part-time in Switzerland. My wife is originally from Switzerland, so we have a little place there. The other part of the time, we're on the road - so it's three different places, really."

. on the lost art of the cowboy song.

TR: "Like a lot of people, including Bernie Taupin, I think the song El Paso by Marty Robbins really was a turning point in popular song history, let alone cowboy song history. Huge hit in 1959, and what an astounding piece of writing.

"Tex Ritter was a great one with Blood on the Saddle, great cowboy singer with a creepy voice, Marty Robbins, not only as a singer but also as a songwriter with all his gunfighter ballads. Johnny Cash's cowboy record - all of Johnny Cash's stuff, in fact. Early Ian & Sylvia had some cowboy stuff on it. Ian wrote Someday Soon and quite a few early cowboy songs. Even more polished groups like The Kingston Trio, The Limelighters and The Brothers Four all had cowboy songs in their repertoire then."

PS: Was that stuff being played on the radio when you were a kid or did you have to go and seek it out?

TR: "Actually, it was being played on the radio. That's what's strange when you look at the fifties. In the same two or three years, you had The Kingston Trio having a Top Ten hit with Tom Dooley, a murder ballad and a hanging song that hit all over the world in several languages, followed by Marty Robbins' El Paso. Tex Ritter was quite popular because he sang the theme song to High Noon, so you actually did hear this stuff on the radio.

"Country music was called country western back then. They got rid of that in the seventies. When they realised cowboy music wasn't hip to pop Walmart audiences, they took the western out of it. But western music was a very strong part of country music and folk music. My brother always had those records and they were important to me.

"He had a Spanish guitar from the border. He's a big influence on me, my older brother. He's a cowboy, livestock contractor in California. He packed horses back into the mountains and he learned a lot of old cowboy songs, but he couldn't carry a tune very well. He ended up reciting the songs. He gave me the guitar because I was wanting to learn three chords and some of those old cowboy songs. I was a teenager, 14, 15 maybe, messing around with Kingston Trio songs and cowboy songs."

PS: I've read that your parents introduced you to Broadway musicals at about the same time. Who were your favourite songwriters there?

TR: "Rodgers & Hammerstein. You know: those early western thematic things like Oklahoma! and Irving Berlin's Annie Get Your Gun, Calamity Jane. The one-off musical, The Music Man, I'm forgetting the guy's name who wrote it [Meredith Wilson], but he was from Iowa. Stuff like that, you know? Well-written classical things - The Sound of Music. Flower Drum Song, that was Rogers & Hammerstein. Those Tin Pan Alley guys really knew how to write a big song when they needed to.

"I was raised one side on Broadway musicals from my parents. From my brothers and sisters it was folk music and cowboy music, so everything was filled with stories."

. on the Rolling Stone journalist Grover Lewis.

PS: The new album's song Scars on his Ankles relates Lewis's boozy encounter with Lightin' Hopkins in 1960s Texas. I got so intrigued by that account that I went out and bought his book.

TR: "He's great. A friend of mine, Bill Stratton, wrote the introduction for that book. One reviewer thought [my song] was a fiction, but it wasn't - that's exactly what happened. A lot of the stuff was words right out of his own mouth."

PS: Why do you think he's been forgotten when other Rolling Stone writers of that era are so lionised?

TR: "He and Paul Nelson, another great Rolling Stone writer who's passed away, neither of them got along with Jann Wenner, the editor. Wenner had enough problem with Hunter Thompson, and these guys were all in the same league, you know? They really got their heads inside a story and put their own lives and opinion in it. Wenner wanted to go somewhere else. Wenner started to rate records, which is a horrible thing. Paul Nelson walked out and Grover Lewis didn't like it either. The whole tone of music journalism changed when they got rid of these guys."

. on his plans to publish a memoir.

TR: "Last time I played the 100 Club, a literary agent came up to me after the show and said, 'You should write a memoir'. We talked and I said 'I'll try'. I think he initially tried a few publishers, who said 'Tom's a great writer, but I don't know what the market would be'. I've kind of started it, but I backed off into thinking I'll just concentrate on these good musical stories and aim it that way. I'm going to take a few more years at it and aim it at my life in music."

. and on a postscript to his Beatles story.

TR: "A reporter from the Los Angeles Herald Examiner was standing next to [me and Bobby Hatfield] listening, and he said 'You did what?' So he took down the story, and I finally found it the other day in an archive. It was called Chip Off The Old Block. I had named myself Tom Berman, the son of the world's greatest gatecrasher, who was actually called Stanley Berman. He used to sneak into big things like the Kennedy inaugeration and stuff like that. I concocted this whole thing - but, anyway, I got to meet the boys."

More Tom Russell pics

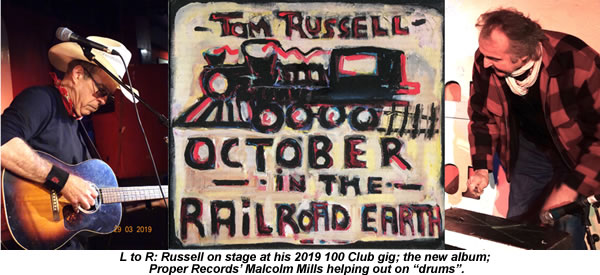

Back at the 100 Club: March 29, 2019

I

returned to see Russell at the 100 Club again on his next visit to the UK, when he was touring the Bakersfield country album promised above. Once again, I have some gig trivia to report:

1) Santa Fe clearly didn't take, as Russell and his wife are now back living in Texas, near Austin. "I sold a lot of art in Santa Fe," he said from the stage, "but it's full of retired people." This move is documented in the new record's Hand-Raised Wolverines, where Russell sings "I'm going back to Texas, mama . The pueblo spirits have flown away from me in Santa Fe".

2) I finally got to hear him do Gallo del Cielo live tonight, though not till after a slightly irritated stage remark about "some journalist" having mentioned he didn't play it on the last UK tour. "It's just so damn long," he explained. Russell had no idea I was there when he said this, of course, let alone that I was the bloke standing two feet in front of his microphone stand at the time. Did I identify myself? I did not.

3) A fan in Bristol, where Russell had played the previous night, believes he's located the site of the unmarked grave mentioned in Isadore Gonzalez, and has placed one of Russell's albums there as a tribute. Gonzales was the Mexican trick rider killed while performing in the UK as part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1903. Russell's song about him is one of the new album's best.

4) He played tonight's gig almost entirely alone, although Malcolm Mills, the owner of Russell's label, helped out on drums during the train song medley. I say drums, but actually it was a sturdy wooden box with a mike propped next to it. Mills' first move on arrival was to chuck away the drumsticks provided and produce a set of brushes from his jacket's inside pocket to use instead. I like to imagine he takes these with him everywhere he goes, like Joey Tribbiani with his fork.

5) In Russell's preamble to the new album's When the Road Gets Rough, we learnt the song was inspired by a journey on 2017's UK tour and that the wine-loving guitarist it mentions was Max De Bernardi.

6) The "Go on, Tom!" bloke was back again, though perhaps not quite as determined as last time. Much more memorable tonight was the Nigerian woman who planted herself squarely in front of the stage as Russell began his second set and announced how much she loved his music. Not a typical Tom Russell fan by any means, but in a room packed with hands-in-pockets, one-heel-tapping, aging white Englishmen like myself, I'm sure he was glad to see someone a bit more demonstrative turn up.