Most bushranger ballads celebrate the thieves rather than their victims. This New South Wales song is an exception.

Most bushranger ballads celebrate the thieves rather than their victims. This New South Wales song is an exception.

The Background

I've taken the set of verses below from a far longer poem by Hubert H Parry, an Australian journalist and performer born in 1903. Parry's original runs to 96 lines, but I've cut it pretty brutally here, leaving just the three dozen lines essential to the core story. Even after those cuts and a few small changes to smooth over the gaps they left behind, the end result's about 98% Parry and only 2% me. (1)

The Ballad

The sun was blazing fiercely on the cracked and dusty plain,

As Peter Clark the drover rode toward his home again.

He rode with one companion, a lad of fifteen years;

A gamer little stockman never cracked a whip at steers.

But Clark was grim and silent as the horse he loved to ride,

Moved on toward the ranges with a long and springy stride.

For, early on that morning, when they'd paused their mounts to change,

He'd spoken with some troopers coming back from Warland's Range.

They'd told him Henry Wilson, just a day or two before,

Had swooped and robbed the mail coach of the golden freight it bore.

They warned the older drover but his laugh was cold and strange,

For well he knew, that evening, they must camp on Warland's Range.

The two men made their camp as darkness fell across the ground,

And soon the weary horses grazed contented close around.

Then, through the inky shadows came a sharp and stern command.

The drovers from their blankets were compelled to rise and stand.

Each faced the deadly Wilson with his hands above his head.

One move, the man informed them and he'd riddle them with lead,

But Clark was calm and silent as the outlaw came in sight.

His thoughts were fast revolving, for he meant to rush and fight.

A gunshot stabbed the darkness with a crimson jet of flame,

The wounded drover staggered, but he came on just the same.

He closed upon the outlaw with a grip of tempered steel.

His blood was flowing freely, but the wound he did not feel.

Yet in such deadly struggle, fate must play a leading part,

The gun, again exploding, shot the drover through the heart,

The drover fell, but falling, threw his sturdy arms around,

The body of the outlaw as they crashed upon the ground.

And thus the plucky drover drew a last and fleeting breath,

With Wilson locked unconscious in his mighty grip of death.

The youngster, mounting quickly, galloped out into the night,

To tell the mounted troopers of the drover's fatal fight.

The troopers raced behind him till the light of breaking day,

Revealed the bloody camp site where in death the drover lay,

Wrapped sound in sleep eternal with his days of droving o'er,

Still tightly gripping Wilson, who would scourge the range no more.

The Facts

There were six men in Peter Clark's droving party as they crossed Warland's Range on the morning of April 9, 1863. At the front of the group were Peter himself, Aston Clarke, whose sister Peter was planning to marry, and a teenager called Samuel Patrick. A little further back came John Conroy, Aston's brother James and Alfred Goodwin, a lone traveller they'd met on the trail about nine miles back. All except Goodwin were on horseback, and none of them were armed.

At about 10:30, with five miles to go before they reached their destination in Murrurundi, they spotted two riders approaching them. Both were moving at full gallop, one a little way in front of the other, and Peter's first assumption was that they must be having a race. Entertainment was hard to come by in this bare country, so he pulled up his horse to enjoy the spectacle. As the two speeding riders came closer, he realised that the one bringing up the rear had a revolver in his hand and that the other man was clearly fleeing for his life. His pursuer was wearing a yellow false beard and a black crepe mask over his face, so it was easy to guess he must be a bushranger.

We know now that the man with the gun was Henry Wilson, who'd already robbed two other men that morning and left them tied to a tree nearby, and that his quarry's surname was Russell. Wilson had sprung out at the young man as he passed along the trail a few minutes earlier, but Russell had decided to make a run for it rather than surrender his valuables.

By

the time Wilson got within 15 yards of Peter and his friends, it was clear he was never going to catch Russell, so he turned his attention to these fresh targets instead. Peter and Samuel, the first in the drovers' party to spot his gun, were already spurring their horses away. Wilson fired a couple of shots at Samuel's departing back, but both missed and the lad kept right on riding. Peter, though, was forced to stop and dismount. Wilson later said he'd spotted a gold watch chain glinting on Peter's waistcoat and decided he was the one in the group most worth robbing. (3)

James and Conroy had caught up with Aston by now, but the three men could get only so close to Wilson before he turned the pistol on them and demanded they dismount. James edged a step or two nearer on foot whenever he thought Wilson might not notice. Here's how his later court testimony described what happened next:

"[Wilson] told Peter to pull off his watch and guard and give it to him and Peter did so. He then told him to give him his cash. Peter told him he had none. He said 'Turn round while I feel your pockets'. At this time, I was about 40 yards away. Peter looked at me as if to say 'Come on, James!'

"He

looked round at me and then he made a plunge on to Wilson. Wilson jumped back and fired at Peter. He was about two yards off and the shot struck him through the neck. At that time, neither of us had been able to lay hands on Wilson. Peter up to this time had done nothing further than attempt to grasp him. Wilson then turned and ran three or four yards away from us. I was then close behind Peter.

"When Wilson ran, Peter and I followed him. Peter was in front of me. Wilson wheeled round and turned one step towards us. He fired and shot Peter through the breast. He turned to run again, when Peter caught him by the ribs on the right side. I then came up and caught hold of him by the throat. Peter fell and the revolver then went off again. [.] I struggled with Wilson and he fell. A few minutes before he fell, Conroy came up and wrenched the revolver out of his hand." (4)

James, Aston and Conroy overpowered Wilson, seeing that he'd managed to shoot though his own hand at some point during the struggle. They tied him up with their saddle straps, kept him covered with his own Tranter revolver and lent Goodwin a horse so he could ride on into Murrurundi to fetch a doctor. But Peter Clark was already dead.

Constable Edward Bruce was riding along the trail near Murrurundi at about 11 o'clock that morning when Samuel found him there and gasped out his news about the shooting. Bruce turned his horse round to head for the crime scene. "I found the body dead at the top of Warland's range," he later testified. "The prisoner was lying on the ground, bound with straps. I immediately handcuffed and cautioned him, telling him I took him in charge for wilful murder." (5)

Constable Edward Bruce was riding along the trail near Murrurundi at about 11 o'clock that morning when Samuel found him there and gasped out his news about the shooting. Bruce turned his horse round to head for the crime scene. "I found the body dead at the top of Warland's range," he later testified. "The prisoner was lying on the ground, bound with straps. I immediately handcuffed and cautioned him, telling him I took him in charge for wilful murder." (5)

Bruce also took custody of Wilson's six-shot revolver, which he found now had just one bullet left. Searching the bandit's pockets and saddlebags, he found Peter's watch, plus a good stash of ammunition and some banknotes. The crepe mask and false beard, both of which had been torn from Wilson's face during the struggle, were lying on the ground nearby. His horse turned out to be one he'd stolen from a man named Walsh on the previous evening.

Goodwin got back to the scene soon after Bruce arrived, accompanied by James Russell, a Murrurundi doctor. Russell examined Peter's body, confirming again that he was dead, and the body was placed in a cart to be taken to the town's Whiteman Hotel for post-mortem examination and a coroner's inquest. Wilson, still handcuffed, was placed alongside the body in the back of the van and - according to one account I've read - complained about the pain of his self-inflicted wound all the way into town. (6)

Wilson was locked up in Murrurundi and identified as the culprit behind a recent mail coach robbery near the town. "One of the drivers states he is positive he is the man," said the Maitland Mercury. Meanwhile, Russell was examining Peter's body and getting ready to give his findings. "There is a wound, apparently a pistol shot wound, about the left ear, near the edge of the whiskers, and passed out about the front of the throat, near the Adam's apple" he told the inquest. "There is also a wound about the centre of the breastbone - a pistol shot. The wound in the breast was the cause of death [which] must have been instantaneous."

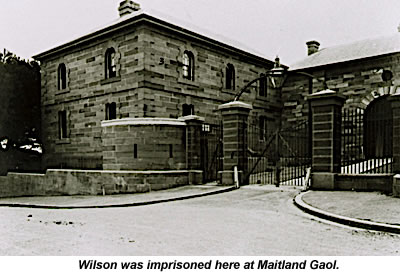

The coroner's jury recorded a verdict of wilful murder and Wilson was dispatched to Maitland Gaol to await trial at the next assizes in September. "Since the inquest was held, we are given to understand the excitement in Murrurundi has been tremendous," April 11's Mercury reported. "The public have with difficulty been kept from summarily dealing with the prisoner." Stripped of the era's delicate language, that means lynch mobs were on the prowl and that the town's lawmen were having a lot of trouble controlling them.

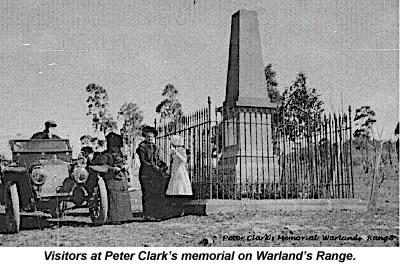

Peter, born to what the Mercury called a "highly respectable" family in nearby Cockfighter's Creek, was a popular figure in the town. In life, he'd been "a fine, well-built, athletic, sober, industrious and deserving young fellow of about 27 years of age", the paper said. He was given a big funeral at Muswellbrook Cemetery, where friends and family raised funds for an impressive monument on his grave. So much money was donated that it paid for a second monument at the murder scene too, which people still visit today.

We jump now to August 1863, and to Wilson's cell in Maitland Gaol. His trial was just weeks away now and he knew he'd almost certainly be sentenced to hang. What had he got to lose by trying to escape instead?

We jump now to August 1863, and to Wilson's cell in Maitland Gaol. His trial was just weeks away now and he knew he'd almost certainly be sentenced to hang. What had he got to lose by trying to escape instead?

First he'd need to deal with the leg irons chaining his ankles together, and then make a rope to help him scale the prison wall. Somewhere, he got hold of a scrap of steel, three inches long and no thicker than a watchspring, which he used each night to saw away at one of his ankle chain's links. When his hand became too sore to continue that work any longer, he switched to slicing strips of fabric from his bed rug and splicing these together into a makeshift rope. The gaol's governor, John Wallace, had told his men to keep a particularly close eye on Wilson, but he still managed to carry out all this work without being detected.

Finally, on Wednesday, August 12, he was ready. With just its final millimetre intact, the chain's link would be easy to snap when he made his move. He tied a small bag of stones to one end of his home-made rope, hid the rope and bag beneath his prison shirt and headed out to the yard for that day's scheduled exercise period.

Wilson walked to the yard's southern wall, swung his rope's weighted end round a few times and then let it fly. Just as he'd hoped, the bag caught fast on the coping at the wall's rim and he was able to start climbing. The guards raised the alarm immediately and drew their guns, ready to fire if he got anywhere near the top of the wall. Wallace rushed to his office for his own pistol, then out through the main gate to wait for Wilson on the wall's far side.

In the event, no guns were needed. Wilson got only seven feet up the wall before his rope snapped, sending him tumbling back into the yard where he was quickly recaptured. "He was immediately put in double irons and will not be allowed to go out of his cell till the trial," next day's Maitland Ensign assured its readers. "He is conscious of the doom that awaits him and this accounts for his desperate attempt to escape from the bonds of retributive justice." A week or two later Wilson tried to slit his own throat, but was stopped by guards before he could do any serious damage. (7)

When his August 31 trial at last began, he first pleaded guilty and then - reminded by the judge that this would throw away whatever small chance he might have - changed his mind. WF Foster and H O'Meagher, the two court-appointed lawyers handling his defence, decided their best bet was to argue their client had never intended to kill Peter, but merely shot him accidentally as the two men wrestled around. If they could convince the jury of this, perhaps they could get the conviction down to manslaughter rather than murder, and so rule out the death penalty.

This tactic rested partly on John Conroy's trial evidence. "Peter rushed at him and Wilson fired at him," he'd testified when describing the two men's struggle. "I think he missed him the first time. Peter still rushed at him and Wilson shot him in the neck. Peter then caught hold of the prisoner and slipped down. Then the prisoner shot him in the breast. I observed that the prisoner had shot through his own hand. I think it was that shot which wounded Peter in the breast." That was also the shot that killed him, of course.

In his summing up, Foster reminded the jury that Russell had confirmed the fatal bullet took a downward path as it travelled through Peter's body, supporting Conroy's memory of Peter slipping down before it was fired. It was possible - even probable - that the revolver had gone off accidentally as the two men struggled, he said. After all, this was a weapon that did not require a separate cocking action, making even the slightest muscular contraction enough to discharge it. It was perfectly possible, Foster contended, that it had gone off with no intention on the part of the prisoner to fire it. And as for the shots he'd fired at Samuel? Why, those were clearly intended only to scare the boy, never to injure him! (8, 9)

It was an ingenious argument - not least because it also explained how Wilson had managed to put a bullet through his own hand - but it did no good. The jury took just ten minutes to return with a murder verdict, and the judge condemned Wilson to hang. "He heard the sentence of death with the same unmoved composure which he had betrayed throughout the trial," the Mercury noted.

The execution was carried out at Maitland Gaol on October 2, 1864. Wilson prayed at the foot of the scaffold for a few minutes with Father Kelly, the prison chaplain, then calmly climbed the steps and allowed the noose to be placed round his neck. He spoke briefly from the platform about his remorse for the killing, and then announced he was ready to proceed. "The rope was adjusted, in another moment the bolt was drawn, and a fine athletic young man of 21 was launched into eternity," next day's Mercury reported. "He died literally without one single struggle. A quicker death is said never to have been witnessed."

Just one mystery remains. From the moment of his arrest onwards, the only name Peter's killer had ever given the authorities was Henry Wilson, but he made no secret of the fact that this was merely a convenient fiction. Even on the scaffold, he remained determined to tell no-one his real name, where he was born or anything about his family. Presumably, his hope was to protect them from the disgrace and pain of being linked to his crimes. All we know is what the Mercury told its readers about him: "He was tolerably well-educated," the paper said, "and was supposed to be respectably connected".

The Music

As far as I've been able to discover, no-one's ever turned these verses into a song. If you'd like to be the first, please send me an MP3 or a YouTube link so I can hear your performance. Another ballad about the case, this one simply called Peter Clark, has been recorded by both John Greenway and Marian Henderson, both of whose versions you can hear on Spotify's PlanetSlade Bushrangers playlist.

Sources & Footnotes

1) I found Parry's original poem in Bill Scott's 1976 book Bushranger Ballads, published by Lansdowne Press. The University of Queensland's AustLit website sums up Parry's biography like this: "In addition to freelance journalist, Parry's occupations include drover, sheep station manager, taxation clerk, performer of musical comedy, supporting artist to Laura Walker, cousin and protégé to the late Nellie Melba and commercial traveller".

2) The Sydney Morning Herald of April 11, 1863, says the drovers had "a mob of cattle" with them on this journey, but I don't think that can be right. None of the many other newspaper accounts I've read mention cattle at all and it's hard to believe they wouldn't have complicated the incident in some way if they'd been present. Edgar Penzig says in his 1994 book Bushrangers, Bandits & Bastards that the drovers were on their way to collect some cattle when Wilson attacked them, which sounds much more likely to me.

3) James Clark testified that he thought Wilson managed to catch Russell at one point. "[He] turned his horse in front of him and presented a revolver at him," James said. "He told the man to stand. I don't think the man stopped." The details here are fuzzy, but the essential point is that Russell managed to get away. By an odd coincidence, he turned out to be the son of James Russell, the doctor who examined Peter's body.

4) I've taken the first paragraph of this quote from James Clark's evidence at the inquest and the rest from his testimony at Wilson's murder trial. My sources are the Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser of April 14, 1863 and September 1, 1863, respectively. The court transcripts refer only to "the prisoner" and "the deceased", but I've substituted the two men's names here.

5) Constable Bruce told the inquest that he was told about the shooting by "a boy who said the man shot was his master". That means it must have been Samuel who stopped him rather than Alfred, who'd simply happened to meet Peter's party on the trail. My assumption is that Samuel must have got to a safe distance after Wilson chased him, lingered there just long enough to hear the gunshots and see Peter fall, and then rode on. Samuel's age is given as anywhere from 12 to 17, quite young enough to be called a boy, but Alfred was 19.

6) The Mercury reported that "a vast number of [Murrurundi's] inhabitants also went out" to the murder scene when Russell was summoned there. Like rubberneckers everywhere, they were presumably glad of a little excitement.

7) Given the strong probability that Wilson would have been shot if he'd reached the top of the prison wall during his escape attempt, I wonder if suicide-by-guard might have been his real objective there too?

8) Wilson offered a similar version of events when talking to Maitland's prison chaplain a month after the trial. He claimed his mask was tugged out of place during his first encounter with Peter, momentarily blocking his vision and causing him to panic. He fired his gun at random, he said, hoping only to wound Peter and make his escape. That was shot one, which struck Peter in the neck. Shot two was the bullet Wilson put through his own hand. Maddened by the pain and somewhat drunk from the alcohol he'd consumed earlier that morning, he said, he started violently struggling to get out of Peter's grip - and that's when the gun went off with its third and fatal shot.

9) Penzig's book includes a photograph showing the Tranter revolver's unusual double trigger mechanism - one inside the trigger guard to fire the gun and another protruding below it to revolve the gun's cylinder and cock its hammer. "If both triggers were pulled simultaneously the Tranter could be fired as fast as (or even faster than) a modern semi-automatic," he writes. "It was this fact which contributed to young Peter Clark's death." If Wilson hadn't been able to fire that third, fatal, shot so soon after the first two, Penzig argues, he could have been disarmed before anyone was killed.