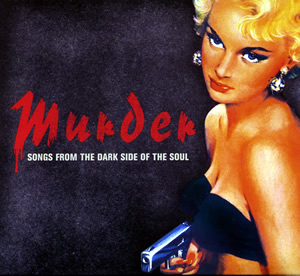

To help PlanetSlade celebrate its first birthday on May 1, those nice people at Trikont Records have given me four copies of their new compilation CD Murder: Songs From The Dark Side of the Soul.

It's a fine selection of early blues, country and calypso from artists like Jimmie Rodgers, Sonny Boy Williamson, Lord Executor, Memphis Minnie, Bessie Smith, Blind Boy Fuller, Louis Armstrong, Champion Jack Dupree, Billie Holiday, The Stanley Brothers and many more. Two of the key songs we've discussed here are on the CD too, with Ethel Waters doing Frankie & Johnny and Archibald tackling Stack-A-Lee.

So: all good stuff, then, and clearly deserving a prime place in your collection. All you have to do to enter our prize draw for one of the four copies on offer is answer this simple question:

Knoxville Girl has its earliest roots in two old English folk songs. Name both of them.

I'll draw four entries at random from all those received by midnight on May 31 (London time), notify the winners by e-mail and get their CDs in the post next day. When you enter, please include a postal address so I know where to find you, and mark your e-mail's subject line “Trikont Murder Competition”. I won't pass your contact details to anyone else, but I might use them to tell you about future PlanetSlade projects. Only one entry per person, please.

Trikont's a great little label - John Peel used to love their stuff - and you should definitely buy as many of their CDs as you can. In the meantime, here's the full track-list for that Murder compilation:

Jimmie Rodgers - Gamblin' Bar Room Blues 2

Ethel Waters - Frankie & Johnny

Sonny Boy Williamson - Your Funeral My Trial

Lord Executor - Seven Skeletons Found in the Yard

Billy Boy Arnold - Prisoner's Plea

Wilmouth Houdini and his Humming Birds - Bandsman Shooting Case

Roosevelt Sykes - .44 Blues

Memphis Minnie - Biting Bug Blues

Bessie Smith - Send Me to the 'lectric Chair

Wade Mainer and Zeke Morris - Down in the Willow

Blind Boy Fuller - Pistol Slapper Blues

A'nt Idy Harper and the Coon Creek Girls - Poor Naomi Wise

Honeyboy - Bloodstains on the Wall

Little Walter and his Jukes - Boom Boom, Out Goes the Light

Louis Armstrong with Louis Jordan - You Rascal, You

Champion Jack Dupree - I'm Going Down with You

The Stanley Brothers - Pretty Polly

Archibald - Stack-A-Lee Parts 1 and 2

Henry Thomas - Bob McKinney

GB Grayson and Henry Whitter - Rose Conley

Billie Holiday - Strange Fruit

Lonnie Johnson - Got the Blues for Murder Only

The Delmore Brothers - The Fugitive's Lament

[NOTE: THIS COMPETITION IS NOW CLOSED. FOR A FULL LIST OF THE WINNERS, CLICK HERE.]

Letters to Planet Slade: April 2010

February 19, 2010. Kelly Bellis of Horizon Surveying Company writes: “You've written a wonderful article on Masquerade! And kudos too for the radio program!!

“There's one item, however, which stood out as uninformed, hitting me so hard between the eyes that I had to stop and jot this down. Near the middle of page 7, you say: "Catherine's Cross is just half a degree off the Greenwich Meridian line. Therefore, when the sun is on the equator - as it is on Spring Equinox - its mid-day shadow points almost exactly due north”.

“Every place on earth has its own local meridian and every place on every day of the year for the instant of its local noon - the time when the sun is at its highest for any given day - all shadows point to precisely due north. The date of Equinox - and it wouldn't have mattered if it had been the Spring or Autumn Equinox - is a fixed occurrence allowing Kit to instruct the precise moment in the determination of the shadow's length.

“Thank you very much for writing this splendid article, I can't wait to get back and finish reading it!”

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for pointing that out, Kelly. Embarrassing as it is when someone catches me out, at least it gives me a chance to look less stupid in the future. I've corrected the offending paragraph now.

[Before making that correction, I contacted Kelly again with a few questions to make sure I'd understood his points correctly. His answers were fascinating, so I'm reproducing our exchange below.]

PS: There's nothing special about the Greenwich Meridian as far as north-pointing shadows are concerned. Whatever longitudinal reading you pick, shadows there at noon (local time) will point due north. Have I got that right?

KB: “That's correct - nothing special about zero longitude in terms of 'Catherine's long finger'; however, understand that it's local solar time.

“Local time is generally understood to mean the local time zone; e.g., Eastern Standard Time. In other words, noon in local solar time is when the sun is at its highest point in the sky for any location and is when any shadow cast is along the meridian of the location; i.e., due north. Noon in local time is generally understood as 12:00 o'clock. The differences between local solar noon and 12:00 o'clock civil time become increasingly greater the further the observer is from the Standard Time Meridian for their time zone and vary daily.”

PS: BUT do noonday shadows point north all over the Earth, or just in the Northern Hemisphere?

KB: “Excellent question. The answer is no, only in the Northern Hemisphere - in the Southern Hemisphere shadows point south. The answer to why is very nicely demonstrated at the Exploratorium. It also neatly addresses the exceptions which exist between the Tropics of Cancer (23° 26' 22" N) and Capricorn (23° 26' 22" S).”

PS: Equally, there's nothing special about the Spring (or Autumn) Equinox as far as shadow length is concerned. Williams could have specified mid-day on any date of the year, and the shadow of Catherine's Cross would have reached just as predictable a length. It would have been a different length from the one on Spring Equinox, of course, but just as easy to predict one year on. Have I got that right?

KB: “As for the aesthetic significance of Equinox and the story in Masquerade, I can't say, but in terms of predicting where the overshadowing end of Catherine's finger would be at mid-day, that specific day of the year would need to be known; eg, August 7, etc. Without knowing the specific date, and only that we're to look at mid-day, we'd have a lovely trench running due north starting at about 9 feet from the base of the monument and over 50 feet long - based upon the approximated height of the monument to be 17 feet and covering all days of the year.

“As an interesting side discussion to this point, and from what I've gathered in various readings, the location marked by Kit with a magnet was based on his observation of the shadow on the day of Equinox. The riddle characteristically only says mid-day, and solar noon is therefore implied.

“What I'd ask Williams, if he could possibly somehow stomach one more Masquerade-related question, is this: Do you recall what the precise time was when you observed the end of Catherine's long finger? I'd expect from Kit, largely based on Bamber's sketch, that he had indeed made allowances for the differences between 12:00 o'clock civil time and local apparent solar time. Such an allowance will account for differences in longitude and the equation of time. ET is significant (ranging between +15 minutes to -17 minutes over the course of a year) and needs be considered in discussing such differences in addition to the observer's longitude.

“For example, if we use my approximated longitude for Catherine's finger (0° 30' 27.25") and calculate the difference in time between local time and mean solar time we get slightly more than 2 minutes and because we're west of the Standard Time Meridian the value is positive. The ET value for March 21 is about +7 minutes 28.7 seconds, and adding the 2 minutes 2 seconds (rounding up to the nearest whole second), we know then to plant the magnet at shadow's end (rounding up to the nearest whole minute) at 12:10pm - or more precisely: 12:09:30.5.”

* The Mummy of Jimmy Garlick.

* The Crossbones Graveyard, a plague pit filled with 15,000 dead (including the local whores, who were called “punchable nuns” in the parlance of the day). Now used as a bus-parking yard by Transport for London to the outrage of some Londoners, who stage a monthly memorial at the site at 7:00pm on the 23rd of each month.

* Hidden wildlife preserve in London: Camley Street Natural Park.

* Museum in the garret of St. Thomas's Church.”

Paul Slade replies: Thanks for those suggestions, Dan. One of the subjects you mention is already on my list of potential Secret London essays, and I will get to it eventually. You'll have to wait and see which one it is, though.”

“Also, apart from The Downhome Boys 1927 recording, do you know of any other versions before 1950 which have the line 'I was standing on the corner'? If you're aware of any, please let me know. I'm interested in musical recordings and lyrics published in books, journals, articles, etc. and it doesn't matter whether the bulldog is mentioned in the lyrics or not.

“I've been researching the legend of Stagger Lee for at least 7 or 8 years now. I've even created a website (The Stagger Lee Files) which you may have come across. Since I wrote the material on that site, I have continued working on the legend and I hope to write some more about Stagger Lee after completing my research. I'm a librarian by trade.

“By the way, Cassell's Dictionary of Slang defines a barking iron as a pistol. It places its use between the late 18th century to mid 19th century. “Thanks a lot for your help on this.”

Paul Slade replies:Don't thank me too soon, Jim. I've just flipped through my Stagger Lee folder again, but I still can't remember where I first came across the notion that the song's bulldog was a gun rather than a wheezing canine.

It would certainly make sense for songwriters like Lloyd Price to place a British Bulldog - as this particular Webley & Scott revolver was nick-named - in Stag's world. Cheap copies of the British Army sidearm were widely available throughout the US in the 1890s, and it's easy to imagine a young city pimp deciding to buy one. Cecil Brown's book tells us that the real Lee Shelton's gun was a Smith & Wesson .44, so in strictly literal terms the Bulldog theory doesn't stand up. In the semi-fictional world of the song, though, giving Stag a Bulldog works perfectly, and that's what makes the theory such an appealing one.

On the other question you raise, I've also listened through all my pre-1950 versions of the song, and aside from the Downhome Boys recording you mention, I can find only one which mentions corners at all - and even that's in rather a different context. It comes on the Memphis Slim/Big Bill Broonzy/Sonny Boy Williamson recording, which David Hirsch's site dates at 1947. The lines in question are:

'Stagger Lee told Mrs Billy Lyons,

If you don't believe your man is dead,

Why don't you look around the corner,

See what a hole he has in his head."

Not quite what you're looking for, I know, but I'm afraid that's the closest I could find.

I'm not sure this has occurred to me before, but now you mention the corner reference in that Downhome Boys version, it strikes me as quite an interesting early sighting of a key thread in the song.

Reed says he was standing on the corner minding his own business when a cop arrested him for no reason. It was then fairly common at harvest time for the cops in some southern towns to round up any black men they could find hanging around, slap a trumped-up charge like vagrancy on them, and ship them off to the nearest prison farm. Once there, they were used to boost the workforce gathering crops at this crucial time of year.

It's this wildly unjust practice which Reed's cheeky little protest verse has in mind, and it could be viewed as a precursor to the Mississippi John Hurt's later question:

'Police officer how can it be,

You arrest everybody but cruel Stagger Lee?'

It's essentially the same thought that's being expressed in each case: why don't the police drop this soft option of arresting innocent black men and go after the real villains like Stagger Lee instead? The answer implied, of course, is that it's because they're afraid of him.

Please do drop me a line again when your new material's up on-line. I read The Stagger Lee Files as part of the research for my own essay, and I'd be fascinated to see any new information you've uncovered.

'Standin' on de conah, didn't mean no hawm

Long come a 'liceman, an' grabbed me by de awm

Took me to de station to hab my trial

De judge gimme thirty days on de ole rock pile.'

“In his autobiography, David 'Honeyboy' Edwards writes about how the vagrancy laws were used to put blacks to work on the plantations. Also, there is a book which documents just how evil these forced labor practices were. In Slavery by Another Name by D. Blackmon, the author shows how lawmen, judges, prisons and businesses (farming and industrial) conspired to re-enslave blacks. Many of them were forced to work in mines, mills and various work camps for years for very minor offenses. Many of them were completely innocent and many of them died due to the horrible conditions.

“Your suggestion that the same type of practice is being protested in Mississippi John Hurt's version of Stagger Lee (with the line asking the police officer why he arrests everybody except Stagger Lee) is something that never occurred to me. And I think you're exactly right. Certainly any black man who had been a victim of forced labor would have been likely to interpret the lyrics in this way.

Returning to The Downhome Boys' version, one interpretation of the song could be that Stagger Lee is a hero for killing Billy--who is cast in the role of a police officer in this version. What goes around comes around. Billy, who is a member of a police force that has been arresting innocent blacks, is killed by a black man, namely Stagger Lee, that he tries to arrest.

“The research that I've been doing for the last several years has focused on the idea that Stagger Lee may have been a much more positive hero than he seems to be. When you look at how terribly oppressed blacks were, and how they lived in a world where good and evil became so twisted and intertwined that it was hard to know the difference between the two, it makes perfect sense that a badman could be a very positive hero for them, not just an anti-hero. So I've been gathering evidence to support this idea.

“For example, you can see that the distinguished black poet Sterling Brown saw Stagger Lee as a great hero through his poem Odyssey of Big Boy. In it, the narrative voice shows his admiration for Stagger Lee by asking that, when death takes hold of him, he be with John Henry, Casey Jones, and Stagolee.”

Paul Slade replies: Have you read HC Brearley's 1939 essay Ba-ad Nigger? It's available in an anthology called Motherwit From The Laughing Barrel, and talks about the appeal of characters like Stagger Lee in black folklore.

Brearley sums up these characters as offering “heroic deviltry”, which I think catches Stag's dual nature pretty well. Like the protagonist of a classic gangster movie, he has to be both a hero and a villain simultaneously - strong enough and free enough for us to envy him, but evil enough to give us a vicarious thrill at his exploits. I'm not sure you can strip out either aspect of that without fundamentally damaging the myth.

Going back to that Downhome Boys version, it's interesting that Stag is allowed to escape at the end, and that we're invited to celebrate that fact. That changes with Mississippi John Hurt's 1927 recording, where Stag hangs at the end. To pursue that gangster movie analogy for a moment, Hurt's approach could be seen as the equivalent of the moralistic ending tagged on to a James Cagney movie to justify all the mayhem that's preceded it.

Perhaps there's a worthwhile distinction to be drawn between versions which allow Stag to get away and those which insist he's punished at the end? We could think of the first group as unambiguous "hero" songs and the second as "anti-hero" ones. I wonder if the second group came about as an attempt to pull in the white audience, and so sell more records? And whether there's been a return to the original approach in very recent recordings? These tend to be more extreme in every other way, so perhaps they're more willing to throw away the idea of obligatory punishment too.

The other thing that struck me reading your letter was the NME placing Tupac Shakur's shooting of two white cops squarely in Stag's tradition, and quoting Dream Hampton's description of this act as "the kind of community work we all dream of doing". There's a bit more about that in the final section of my own essay, and that section touches on Stag-as-hero in a couple of other ways too.

“Some, such as Cecil Brown, have recognized it, but still this part of the legend has not really been fully explored. Writers say that blacks idolized Stagger Lee because he was so bad that nobody would mess with him, including the white man's law. Greil Marcus referred to this as 'a fantasy of no limits'. But I believe that Stagger Lee was a hero for more than just this; I think he was a hero for performing acts which were truly heroic.

“For example, Cecil Brown believes that the Stetson represented manhood and the fight over it symbolized a fight for manhood. In my writings on my website, I suggest that if the fight was a fight for manhood, then it could also be symbolic of the fight for black freedom. I believe I have a good amount of evidence to support the idea that Stagger Lee was a freedom hero. Some of it is in my Stagger Lee Files website, but I've found much more evidence in the years since I wrote the essays that appear there.

“I'm not trying to romanticize Stagger Lee. I recognize the darker side of the legend, especially as can be seen in the toasts and in the more recent recordings to which you make reference. And I recognize that not all African Americans loved Stagger Lee or saw him as a hero. Mississippi John Hurt did not see Stagger Lee as any kind of hero. He was a gentle soul who probably objected to the violence perpetrated by the badman.

“Regarding versions of Stagger Lee in which he escapes punishment, a key version would be Lloyd Price's. His recording sounds like a celebration of Stagger Lee's killing of Billy. I believe that Price saw Stagger Lee as a hero. The ending to the Downhome Boys' version is interesting because it seems to serve as a warning that he's out there and could strike again. But Stagger Lee can be a hero even if he is killed. As Greil Marcus noted, Stagger Lee's death gave him the opportunity to go down to hell and defeat Satan.

“I don't know much about Tupac Shakur. Wikipedia says he was a rapper and social activist who advocated egalitarianism. His intervening when he thought two cops were harassing a black man remind me of Sterling Brown's poem The Ballad of Joe Meek. I think Shakur may be on his way to becoming a mythical figure himself. I remember one day in the library hearing a couple of black kids argue about whether he was really dead.

“Your essay also struck a chord with me when you wrote about Russia's gangsters. I've come across evidence that other cultures do celebrate their badman heroes in song. There is a book by Elijah Wald titled Narcocorrido which explores 'a genre of ballad that glorifies gun-toting drug lords in a Mexican version of gangsta rap'.

“I once got an e-mail from someone telling me about a contemporary Stagger Lee-like hero in Portugal nicknamed Pica. He was a 10-year-old car thief who stole cars from people by threatening to stick them with a hypodermic which he claimed was infected with the HIV virus. (I was told that Pica means needle.)

“According to the story, he wreaked so much havoc that his own parents set him up for the cops to arrest him. He died in prison and now is celebrated in Portuguese rap songs. Some of his idolizers have custom paint jobs on their cars depicting Pica steering their vehicles from above.”

Paul Slade replies: The idea of Stag as an unabashed freedom fighter dovetails neatly with the real Lee Shelton's career in St Louis party politics, and I'll be interested to see you develop some of these thoughts on your site. I love that story about Pica too, and I'm going to ask PlanetSlade's readers if they can supply any more details about him - the myth or the reality. I want to see some photos of those Pica paint-jobs too!”

And finally...

PlanetSlade's thanks this month go to Max Welton of Langley in Washington state. Max was kind enough to mention my Masquerade essay on Metafilter's main board, and the link he included there sent a couple of thousand extra visitors scurrying over this way. You can find the resulting discussion here.