Kirby's original hope had been to give his Fourth World story a proper ending, close the comics themselves down, and then collect the whole saga into a series of what we'd now call graphic novels. Unfortunately, he never got the chance. Citing poor sales, DC closed New Gods and The Forever People after just 11 issues each, and Mister Miracle after only 18. By 1974, it was all over. Kirby invented, wrote and drew a handful of unconnected books for DC after that, including The Demon, Kamandi and Omac, but returned to Marvel in 1976. DC retained ownership of all the characters Kirby had created there, and still uses them to this day.

Kirby's original hope had been to give his Fourth World story a proper ending, close the comics themselves down, and then collect the whole saga into a series of what we'd now call graphic novels. Unfortunately, he never got the chance. Citing poor sales, DC closed New Gods and The Forever People after just 11 issues each, and Mister Miracle after only 18. By 1974, it was all over. Kirby invented, wrote and drew a handful of unconnected books for DC after that, including The Demon, Kamandi and Omac, but returned to Marvel in 1976. DC retained ownership of all the characters Kirby had created there, and still uses them to this day.

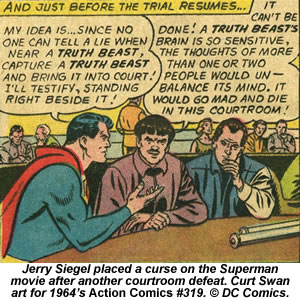

The Superman wars broke out again in 1966, when his initial 28-year copyright term came to an end, and Siegel and Shuster filed notice to terminate. That case dragged on till 1975, producing another defeat for the two men and hints from DC that it might give them a pension if they dropped plans for a Supreme Court appeal. Both in their sixties by then, suffering from poor health, and struggling for cash, they wearily agreed.

Six months later, with Richard Donner's 1978 Superman movie on the horizon but still no pension from DC, Siegel decided it was time for desperate measures. He wrote a long, angry screed placing a curse on Donner's movie and sent copies to every news organisation he could think of. “I hope it super-bombs,” he wrote. “I hope loyal Superman fans stay away from it in droves. I hope the whole world, becoming aware of the stench that surrounds Superman, will avoid the movie like the plague.

“The publishers of Superman comic books, National Periodical Publications Inc, killed my days, murdered my nights, choked my happiness, strangled my career. I consider National's executives economic murderers, money-mad monsters.” (26)

Siegel was working as a mail clerk by the time he wrote that press release, earning just $7,000 a year, and Shuster was legally blind. No newspaper could resist a headline like “Superman's creator curses movie” - particularly when the two protagonists presented such a heart-rending picture - and this was not the kind of publicity DC or Warners wanted for such an important project. Comic book artists Neal Adams and Jerry Robinson led a three-month campaign to win decent treatment for the two men.

Warners' fear, Robinson said, was that giving even an inch of ground to Siegel & Shuster's pension demands would leave it open to a renewed legal challenge over Superman's ownership. “The thing that gave us leverage was the upcoming movie,” he added. “We were giving Warners bad publicity about the creators of the biggest property of the 20th Century.” (11)

Warners finally caved in, giving Siegel and Shuster a yearly pension of $20,000 each which would climb steadily for the rest of their lives, and the medical insurance they sorely needed. “There is no legal obligation,” Warners executive vice president Jay Emmett told the New York Times. “But I feel sure there is a moral obligation on our part.” Donner's Superman movie opened in December 1978, grossing over £300m, and becoming Warner Brothers' biggest money-maker to date. Siegel and Shuster were given a place in the credits as Superman's creators. Their pensions continued to climb, just as Warners had promised, reaching $85,000 a year each by the time Shuster died in 1992 and a reported “six figures” when Siegel followed four years later. (12)

Speaking just after Siegel's death, Adams argued that the pensions deal had actually been a good thing for DC, as well as a help to Superman's creators. “It enabled DC Comics and Warners to actually think better of themselves,” he said. “In spite of the fact that there was such reluctance to take care of these fellows and to put their names back on this property, it seems to me that everybody profited by this.” (11)

By 1996, Siegel and Shuster were both dead and the five-year window opened by Superman's 56th anniversary had just three years left to run. Joanne Siegel and Laura Siegel Larson - Jerry's widow and daughter - announced plans to file for termination in 1997, and that's the case Toberoff is steering through the courts now. “This is a widow and child trying to vindicate their father, vindicate their spouse,” says Trexler. “They're trying to vindicate someone who'd spent his entire life feeling he'd created something and hadn't been duly recognised for it. This is a battle they're fighting for him.”

Back at Marvel, Kirby found - just as Siegel had at DC - that his status as one of the company's founding fathers cut little ice with the young editors now managing his work. Kirby was both writing and drawing Captain America's book, as well as creating new titles like The Eternals, Devil Dinosaur and Machine Man. Marvel had turned Kirby's lay-outs and storytelling techniques into a house style, which it expected all subsequent artists to follow, but he received little respect from the new generation of staff there. To them, Kirby's own pages now looked quaint and old-fashioned.

“Staffers seeded the letters columns of Kirby's books with negative comments - some of which were fake - in a seeming attempt to spite him,” Raphael and Spurgeon say in their 2003 Lee biography. “They referred to him as 'Jack the Hack'. Some editors scrawled derisive comments on copies of Kirby's pages and pasted them on their office doors. [...] On more than a few occasions, Kirby was aggravated by the ingratitude of the company he had helped build. Stan had to step in to smooth things over.” Kirby stuck it out at Marvel only until May 1978, when he quit and moved into animation work, sometimes on Marvel projects like The Fantastic Four's TV cartoon, sometimes for other clients such as Disney.