It was also in 1978 that a change to US law demanded corporations like Marvel be able to back up their work-for-hire claims with written documentation. No-one had ever imagined that a comic book character would be worth any serious money when all the longest-running and most profitable heroes were being created, and everyone knew that those characters' legal status rested on some very shaky foundations.

It was also in 1978 that a change to US law demanded corporations like Marvel be able to back up their work-for-hire claims with written documentation. No-one had ever imagined that a comic book character would be worth any serious money when all the longest-running and most profitable heroes were being created, and everyone knew that those characters' legal status rested on some very shaky foundations.

Often, the evidence amounted to little more than a now-disputed notion of what had been accepted practice 40 years earlier, or a freelancer's scrawled signature on the back of his pay cheque. As we'd soon learn, publishers were not always able to produce even this very basic documentation in court because it had been either lost or destroyed. Marvel decided it had better get its paperwork in order, and it was partly the increased stringency of the proposed new contract it gave Kirby which prompted him to quit.

The other big issue in comics at that time was the question of publishers' obligation to return original art to the artist who'd drawn it. Until the 1970s, when a collectors' market for this art started to emerge, original pages were routinely left to rot in a disorderly storage room, given away to people visiting the publisher's office or stolen by staff. Artists maintained that all they had sold was the reproduction rights to that art, and that the originals should therefore be returned, but in practice only those prepared to kick up a real fuss ever got their art back.

DC began returning all new original art in 1973 and formalised this arrangement in its freelancers' contracts five years later. It also cleared its backlog of unreturned art, finally sending out the pages it had held for so long and paying cash compensation for those it had lost. Marvel began returning new pages at about the same time as DC, but didn't even start cataloguing its art stockpile until 1975. As the prices original comics art fetched at conventions began to climb, artists realised what a valuable resource it was, and piled more and more pressure on Marvel about it. With its only major rival already having put its house in order, and fearing a huge sales tax bill if it claimed to own the art, Marvel knew the issue would have to be tackled.

Meanwhile, Kirby had worked out that he'd drawn around 8,000 pages of art for Marvel which the company had never returned, and used his 1978 departure to demand it all back. “I guess his contract ended in the Summer,” Jim Shooter, then Marvel's editor-in-chief, later recalled. “I was called into a meeting with upstairs management and lawyers and told Jack was at least intimating that he might do a number of legal strategies to re-capture ownership of characters he'd been creator or co-creator of.” (19)

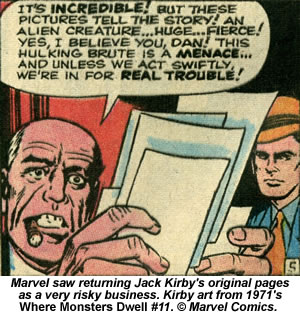

Marvel's attitude at that point was that the legal dangers of returning Kirby's art far outweighed any possible benefit for the company. “At one point, Marvel's legal team told Shooter that giving away original art would be tantamount to giving away corporate assets,” Raphael and Spurgeon say. “At another time, they feared it could be interpreted as legitimising any assertion Kirby might make of copyright ownership.”

Marvel completed cataloguing the 35,000 pages of art it then held in February 1980. Four years later, it wrote to all the company's freelancers - past and present - listing the art of theirs it held and offering to return it if they signed the enclosed one-page form. This stated all their assignments for Marvel had been strictly work-for-hire, and that the company alone owned all the copyrights in that work and any characters it contained. “Anybody who signs that form is crazy,” said Neal Adams. (27)

The standard form was bad enough, but the one Kirby received was far worse. His document was four-pages long, and asked him to give up more rights than anyone else. It offered him not ownership of the 88 pages listed, but merely “physical custody”. He would not be allowed to sell the art, display it, give it away or profit from it in any way. Marvel, on the other hand, could demand the art back at any time, use it for whatever business purposes it saw fit and modify it in any way. Kirby would have to accept that any copyrights in that art, under current or future law, belonged to Marvel “in perpetuity”, and that he had no right to claim any of the remaining 7,900 pages of his Marvel art which he believed the company was still holding.

“It was in fact a contract assigning Kirby to be Marvel's storage facility,” say Raphael and Spurgeon. Not surprisingly, he refused to sign it.

In its way, this contract was simple confirmation of the damage losing Kirby's characters would do to Marvel's prospects. No other artist merited such a hard-line approach, because no other artist's work formed such a crucial cornerstone to everything that had followed. Marvel was still The House That Jack Built, and it was precisely that fact which led the company to treat him so badly. Kirby later parodied this approach with a company he called GodCorp and it's motto: “Grab it all. Own it all. Drain it all”. (28)

Marvel stonewalled Kirby's attempts to get the art agreement redrafted, and he replied with a letter formally broaching the subject of a copyright challenge. The famously feisty Comics Journal launched its campaign protesting Marvel's treatment of Kirby with a fiery editorial. “You don't need to have grown up reading Jack Kirby's work to realise that Marvel Comics' treatment of him is criminal, to see their contempt and ingratitude toward a man who practically single-handedly erected their company,” wrote editor Gary Groth. “If Marvel had a sense of decency (or shame) they'd offer Kirby a royalty on characters he created. At the very least, they should return his damned art.” (29)