September: Duncan & Brady

June 25, 2017. Barry Nester of Jerusalem in Israel writes:

“I’ve just read your essay on Pretty Polly, and want to thank you for it. What a wonderful, interesting and thorough piece of research!”

“May I suggest that you consider writing an article about Duncan and Brady? It only gets a half-page on Wikipedia, and I’m sure you could do better. For example, when did James Brady become King Brady? The only record I have with it is Tom Rush’s Got a Mind to Ramble. It’s the same version that Dave Van Ronk sings on YouTube. The two opening verses are the best I’ve ever heard in any ballad:

Oh well it’s twinkle twinkle little star

‘Long comes Brady in his electric car

Got a mean look in his eye

He going to shoot somebody just to see him die.

Been on the job too long

Oh well it’s Duncan Duncan tending the bar

‘Long comes Brady with his shining star

Brady says to Duncan: “You’re under arrest!”

Duncan shot a hole right through King Brady’s chest.

Been on the job too long

“In a short essay, Terry’s Songs says that the first police cars in the US were electric, which explains the mention in the first stanza. There’s a longer and more informative essay in Sing Out!, but I think you could improve upon it. Even if not, it still should appear on your blog, because that’s where people would look for it.

“There are some interesting variants of the song [in Dorothy Scarborough’s 1925 book On the Trail of Negro Folk Songs], where the claim is made on page 85 that it took place in Waco, Texas.

“Hope this will inspire you!”

Paul Slade replies: Thanks very much for the kind words, Barry – and thanks for passing on that fascinating detail about the real electric police cars too. It’s a line in the song that’s always puzzled me, so it’s good to have it explained at last. The “shoot somebody just to see him die” line always sticks in my mind too, and was presumably the inspiration for Johnny Cash’s very similar motivation in Folsom Prison Blues: “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die”.

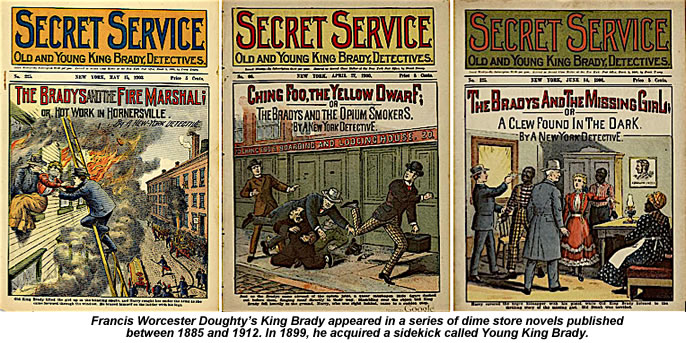

The earliest example I can find offhand of the “King Brady” reference being used in the song is in Leadbelly’s 1947 recording, but there may well be earlier ones I’m not aware of. I do know there was an American pulp magazine character called King Brady (first name James), whose tough-guy detective adventures had already been running for five years when the real James Brady died. I imagine our Brady must have got his nickname from that source, but whether it was given him by his fellow cops, the local bad boys or an enterprising songwriter I don’t know.

I’ve discussed Duncan & Brady very briefly on PlanetSlade here, where I talk about it as the possible source of Stagger Lee’s “dressed in red” line. Like the killings described in Stagger Lee and Frankie & Johnny, the Duncan & Brady murder took place in the notorious Deep Morgan district of 1890s St Louis. This proximity has often led to the three songs borrowing images and phraseology from one another.

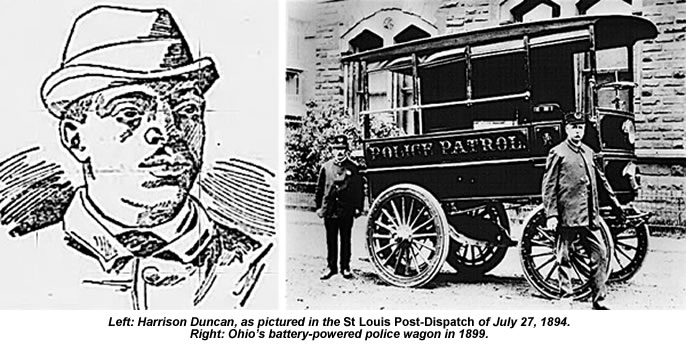

There can be no doubt about Duncan & Brady’s location or the date on which James Brady died – October 6, 1890 – as we still have the original press coverage. Stagger Lee is often said to be based on killings in other cities too, but these claims generally spring from no more than a half-remembered rumour someone thinks they might once have heard. That’s the heading I’d put this Waco stuff under.

There can be no doubt about Duncan & Brady’s location or the date on which James Brady died – October 6, 1890 – as we still have the original press coverage. Stagger Lee is often said to be based on killings in other cities too, but these claims generally spring from no more than a half-remembered rumour someone thinks they might once have heard. That’s the heading I’d put this Waco stuff under.

I’ve got no plans to write a full PlanetSlade essay about Duncan & Brady at the moment, I’m afraid – you’ll appreciate those require quite a big investment of time on my part – but I may get to it one day. In the meantime, I’ve done a bit of basic digging around, and found a few nuggets you might enjoy.

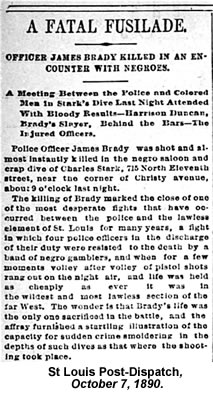

The St Louis Post-Dispatch’s first report of Brady’s killing, which appeared in the paper’s October 7, 1890 edition, gives a long and fairly lurid description of the previous night’s events at Charlie Stark’s saloon, a joint frequented by the city’s black crap shooters. The trouble there seems to have started when a cop named Gaffney tried to break up a fight on the sidewalk outside, and was twice knocked to the ground with a heavy cane in response. Gaffney summoned reinforcements – Brady among them – and the four cops charged into Stark’s to make their arrests.

They were immediately faced by a group of armed black customers and saloon staff, none of whom had any interest whatsoever in coming along quietly. A gunfight broke out between the two sides, and soon the air was filled with whistling lead. The best description I’ve found of the role played by Duncan and Brady themselves in all this comes from the St Louis Post-Dispatch of November 4, 1892:

“While the battle was at its height, officer James Brady dashed in the front door. He saw Harrison Duncan at the foot of the stairs which he had descended when the officers came in, using his revolver with deadly intent. Brady fired a shot and advanced on Duncan, who returned his shot and ran across the room to the bar, behind which he retreated.

“Brady fired at his head as he peered over the bar and Duncan fired back. Brady then made a bold move. He ran to the bar, climbed upon it and, bending over until he could see Duncan, he shot at him. Duncan jumped to his feet and, placing his weapon within a foot of Brady’s breast, he shot him through the heart. Brady fell to the floor and gasped: ‘I’m shot through the heart’.

“Officer Connors, who had emptied his revolver, boldly advanced on Duncan and, pointing the empty revolver at his head, ordered him to throw up his hands. Duncan did so and the battle ended.”

Brady died on the spot. His colleagues arrested Duncan (who hadn’t known Connors’ revolver was empty, of course), plus two other men who’d shot at them. Later reports tell us that a total of 25 bullets were fired by one side or the other in the course of the fight. There were plenty of injuries on both sides – Gaffney had been beaten with billiard cues at the top of the stairs and Duncan had a couple of bullets in him - but Brady was the only fatality. “Officer Brady was appointed on the force January 19, 1886, at which time he was 26 years of age,” the Post-Dispatch tells us. “[He] had made an excellent record as a fearless and efficient officer”.

There’s a couple of things there which are quite interesting in the context of the song. “Shot a hole straight through King Brady’s chest” seems a pretty accurate description of what really happened: a point-blank shot to the heart. “Been on the job too long” looks a bit more doubtful, though. If the newspaper’s details are correct, then Brady had been a cop for less than five years when he died. He left behind a widow and four young children, the youngest still a baby.

Duncan’s lawyers, a firm called Farner and Royse, secured a change of venue for his trial, and did all they could to delay its date. It was not until November 3, 1892, that a jury in Clayton, St Louis County, found him guilty of first-degree murder for Brady’s killing. The appeals went all the way to Missouri’s Supreme Court, but to no avail. Still Duncan’s friends fought on. Just ten days before his scheduled execution date, one group was still organising events to fund a US Supreme Court appeal.

Many people believed Duncan should have been convicted only of second degree, rather than first degree, murder and therefore have escaped the death penalty. First-degree murder requires that the killing must have been planned in cold blood, and this is the definition Duncan’s supporters argued his case did not meet. Their views are best summed up by this statement from R. Lee Mudd, the case’s prosecuting attorney, which was published in the Post-Dispatch on July 27, 1894:

“When Duncan was tried, the Court should have instructed the jury for murder in the second degree. […] There was nothing in the evidence at all to show that he killed Brady in cold blood. On the contrary, the testimony proved that Duncan only fired when three policemen were trying to kill him. I do not want to appear as condoning Duncan’s crime, for I believe him to have been a thoroughly bad man. I wrote a long letter to Gov. Stone, but he declined to interfere on the ground that he did not propose to be made a court of last resort.”

As Mudd suggests here, Duncan does seem to have been a pretty violent character. The press reports claim he was the man who knocked Gaffney down outside the saloon, and was fleeing that officer when he ran upstairs towards Stark’s billiards room. Gaffney followed him up the stairs, but was promptly set upon by the same gang he’d seen outside who, the Post-Dispatch says, “ beat him with billiard cues, knocked him down and brutally kicked him”. Duncan had just returned downstairs when Brady first saw him.

Mudd also suggests it was the police who shot first, which would explain the song’s view that they were needlessly throwing their weight around in a room full of innocent gamblers:

Brady, Brady, Brady, well you know you done wrong,

Breaking in here while my game’s going on,

Breaking down the windows, knocking down the door,

Now you’re lying dead on the bar-room floor.

Duncan was hanged at 6:29am on July 27, 1894, at Clayton courthouse. He was left hanging there for 27 minutes, and then cut down and buried in an unmarked grave at Friedens Cemetery in St Louis County. The Post-Dispatch describes a small crowd of women watching the execution from the courthouse roof, and reports overhearing two of them avidly rehashing its details over their hotel breakfast an hour later.

June 27, 2017. Barry Nester adds:

“Thank you so much for your reply. It’s quite amazing, the amount of information you manage to amass in a short time.

“Now I’m thinking more general thoughts. At the end of the 19th century, there were black ghettoes in all major American cities, and many minor ones, too (St. Louis was never a major city). These areas all had red-light districts with bars and bordellos and poor folk eking out short violent lives, ‘served’ by corrupt police, and peopled by the children of freed slaves who escaped the South. Murder was rampant. And yet, only Deep Morgan in St. Louis produced three immortal ballads in ten short years. Why was that? What was so special about Deep Morgan?

“And who wrote the ballads? Blacks? Whites? Were they residents of Deep Morgan, did they personally know the characters in the ballads, or did they get their information from the newspapers? Did they make a living out of the ballads, by selling sheet music, for example? Or did they just write them for the hell of it?

“The songs are wonderful and memorable. Did the same composers write other songs?”

Paul Slade replies: I’ve talked a little about the factors which made 1890s St Louis such a violent place in my Stagger Lee essay. As for Deep Morgan in particular, I guess the fact that it hosted so much of the city’s vice industry simply meant that the murder rate there was much higher than in other neighbourhoods. For any balladeer in search of material, where better to turn than the press reports and rumours describing each night’s violence there?

St Louis had a very lively jazz, blues and ragtime scene in the 1890s, and nowhere more so than among the resident piano players in its many bars and brothels. It’s no coincidence that “Father of the Blues” WC Handy chose the city for one of his first really successful compositions. I’m thinking of St Louis Blues, with its gritty lyrics describing a broken-hearted woman whose callous, crap-shooting husband has been tempted away by a flashy St Louis dame.

The city wasn’t unique in any of this, of course, but take those factors together and I think we start to see why it’s been able to punch so far above its weight in the murder ballads world. The only place I’ve found with the same concentration of these songs is North Carolina, where the area round Winston-Salem produced the killings described in Tom Dooley, Poor Ellen Smith and Murder of the Lawson Family. Those three murders span a period of 63 years, however, against the mere ten years it took St Louis to give us Stagger Lee, Frankie & Johnny and Duncan & Brady.

There’s no simple answer to the questions you ask about the ballads’ origins, and I’ve come across examples of all the possibilities you mention. Frankie & Johnny can be traced to a black St Louis pianist who’s said to have written it on the day after the murder, Knoxville Girl’s tale comes from a 17th century English folk song and Poor Ellen Smith was written by the killer’s cellmate. Murder of the Lawson Family relied on press coverage, while Pretty Polly seems to have begun with a conversation in a dockside pub. North Carolina mountain musicians were already singing Tom Dooley within a year of the murder, but which one of them wrote it remains a mystery.

As far as getting paid is concerned, I’ve come across at least one ballad which was regularly sung at the murder scene by its composer, who passed a hat to collect contributions from the listening visitors when he was done. For most musicians of the 1800s – which is when many of these songs began – informal live performances were the only way of making money from their work. Adding a topical local song to your set, whether you’d written it yourself or not, presumably helped to pull in a bigger crowd and encouraged them to fill the tip jar.

My book, Unprepared To Die, covers all the songs I’ve mentioned here, and contains a lot of material which appears nowhere online. For a much fuller discussion of all the subjects we’ve touched on, including two exclusive new essays, please consider buying a copy. You can buy individual chapters to read on your Kindle or other device too.

Rattle on the Stovepipe winners

The four Rattle on the Stovepipe CDs from PlanetSlade’s June competition were won by: Seth Forstater of Excelsior, Minnesota; James Closs of Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire; Gary J Smith of Matheson, Ontario, and Joe Offer of Applegate, California.

They all correctly identified Henry Whitter as the man who first put Poor Ellen Smith on disc. No-one fell for my little ruse of including Henry Winkler among the possible answers, which is just as well as he’s actually the man who played the Fonz on Happy Days.

All the winners have now safely received their CDs. “I listened to it in my car and it sounds great,” Gary Smith told me. “Those guys can really pick.” Many thanks to RotS’s Dave Arthur for donating the CDs, and also to everyone who entered.

Solving 1904’s Islington clue

Back at the beginning of May, I got an e-mail from a TV production company. They had the contract for making a popular BBC Two documentary series, and were thinking of including an item on the Treasure Hunt Riots in its next run. Would I be prepared to walk around a few key sites with the presenter while they filmed me telling him the bare bones of the story?

That particular PlanetSlade article, you’ll recall, describes a 1904 treasure hunt organised by a newspaper called the Weekly Dispatch, which hid valuable prize medallions all round the UK and then printed a series of clues telling its readers where to find them. The result was widespread chaos, vandalism and heavy fines.

It’s a story which deserves to be better known than it is, so I agreed to take part in the episode. We decided to focus on the paper’s Islington clue, partly for logistical reasons, but also because it’s one of the few instances in which we’re sure of the medallion’s final hiding place.

A date was fixed to scout some suitable locations, and I spent a very enjoyable afternoon wondering round Islington with the programme’s researcher and her cameraman. They gave me a date for filming and then, two weeks before that date came round, contacted me again to say someone higher up the ladder had decided they didn’t want to do this item after all. That was a bit disappointing, of course, but I’ve been around enough media projects of various kinds to know that these things happen. Hey-ho.

Why am I telling you all this? Because the production company’s call prompted me to do a bit of fresh research on the story, and now that they don’t want it, I’m free to share the fruits of that research here.

First of all, I dug out some more information on the use of mounted troops to clear treasure hunters from Woolwich Common, which I’ve written up in the yellow box here. Then I contacted Mark Aston and Oonagh Gay at Islington Museum, who were able to help me solve the clue and reconstruct exactly the journey its man took to hide that particular medallion.

The Weekly Dispatch took several clues to describe its man’s full journey round Islington, and only one of these has survived. What I’ve got here, therefore, does not include the moment when he finally concealed the disc. I’m going to run the clue bit by bit and explain our conclusions as we go along. It first appeared in January 1904, remember.

“The position selected at the entrance gates to the public institution certainly seemed a favourable one; but I ultimately decided not to make use of it because a search at this particular spot might cause some slight inconvenience to the neighbours.

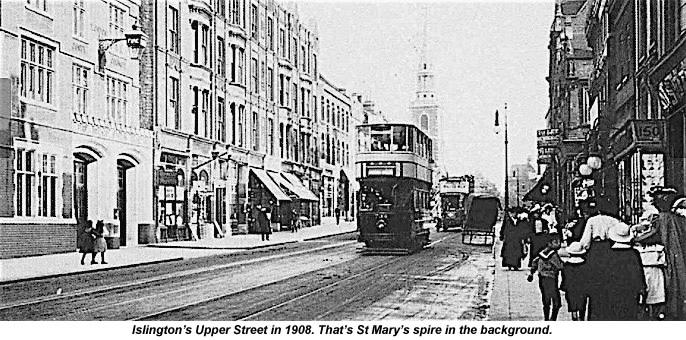

We can’t identify the gates mentioned here, but the next paragraph tells us they must have been very close to St Mary’s church and the King’s Head theatre pub, both of which still stand in Upper Street today.

“I accordingly followed the road northwards for about half a mile, and then turning sharply to the left, passed down a broad thoroughfare which led beside a railway station, and so out into an important main road along which tramway cars and omnibuses were running.”

The only railway station which makes sense in the context of the clue as a whole is Highbury & Islington, which the hider must have approached along Upper Street. Starting half a mile south of the station puts him just outside St Mary’s when he started. The left turn at Highbury & Islington takes him into either Highbury Station Road (a sharp turn) or Holloway Road (a broad thoroughfare). Either of these routes would lead him to the busy Liverpool Road, which the museum’s 1916 Ordnance Survey map confirms was a tramway.

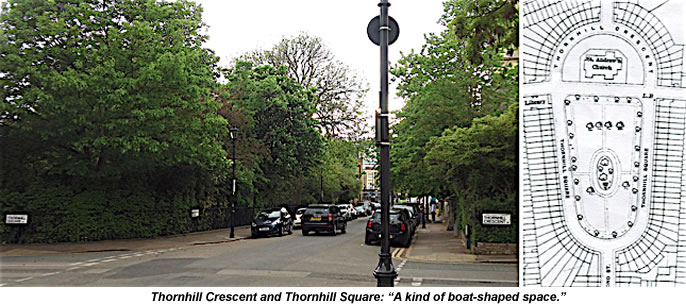

“Turning southward and then westward, I reached a spot where a square and a crescent stand side-by-side and form a kind of boat-shaped space, the centre of which is occupied by two gardens, one of which contains a public building. The path running round these enclosures seemed well suited for my purpose, and I made a note of it before going further to see if a better one would offer itself.”

Southward down Liverpool Road and then west into Lofting Road brings you to Thornhill Crescent and its adjacent Thornhill Square. Viewed from above, these two tiny parks combine to form the shape of a boat’s hull. Thornhill Crescent is occupied by St Andrew’s church, which makes that our public building. It would have been easy to reach through the parks’ metal railings from the surrounding pavement to press a medallion into the grass and mud inside.

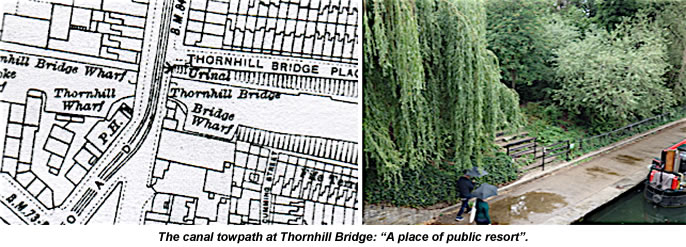

“Continuing my way, I presently passed through a street containing numerous shops, and so reached a bridge, by the side of which stands a place of public resort. Some steps not far away led down below the bridge, and here I found abundant corners which promised to lend themselves to my purpose.”

Continue a few yards along Lofting Road and you come to Caledonian Road, then (as now) a street with plenty of shops. A left turn into Caledonian Road brings you to its bridge over the Regent’s Canal at Thornhill Wharf. The “place of public resort” here baffled me for ages, but once again it was the museum’s 1916 Ordnance Survey map which came to the rescue. Some tiny type by the side of the bridge reveals there was once a public urinal there, right next to the steps leading down to the canal towpath. As at Thornhill Crescent, there would have been plenty of places to hide a medallion in the towpath’s shrubbery and mud.

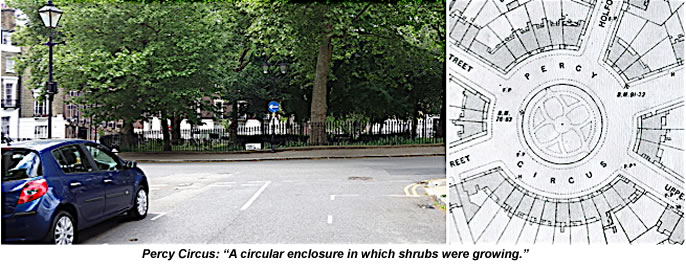

“Accordingly, I made another note, and then going still southwards, I struck a somewhat steep main thoroughfare, up which I passed for a few yards, and then turning off through a network of streets, reached a circular enclosure in which shrubs were growing.”

Continuing south along Caledonian Road brings you to the junction with Pentonville Road, which slopes quite steeply up towards the Angel. There are several right turns off Pentonville Road which could lead you through that area’s jumble of streets to Percy Circus, which is still circular and still full of shrubs. Quite a few treasure hunters were arrested here in 1904, as I describe in the main article.

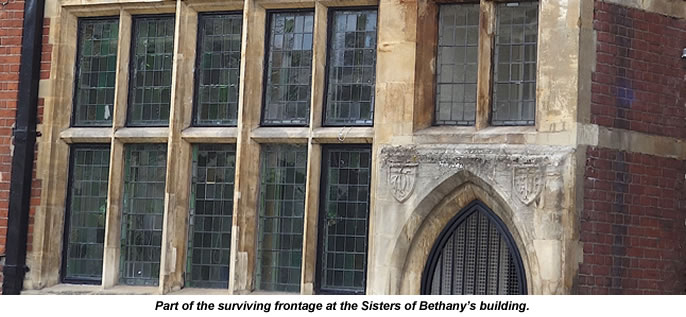

“Near to this stood a square containing a religious institution noted for its beautiful needlework, and near at hand stood two other small squares.”

The nearby square with a religious institution is Lloyd Square, where the Sisters of Bethany once ran a church embroidery school. Granville Square and Willmington Square are both close at hand.

The Islington prize medallion was eventually found outside St Mary’s church in Upper Street, which means the hider’s route took him in a large circle, both beginning and finishing at that spot. Figuring all this out and walking the resulting route in full was a lot of nerdy fun.

Many thanks to everyone at Islington Museum for their help in solving this clue.

June: Win a Rattle on the Stovepipe CD.

Dave Arthur of the excellent UK folk trio Rattle on the Stovepipe has been kind enough to give PlanetSlade four copies of the band’s new CD to give away. For your chance of winning one, just answer the question below.

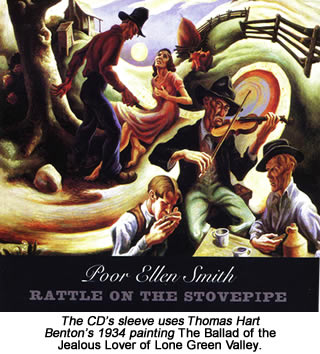

As you can see from its sleeve, the whole project’s got a distinctly “murder ballads” vibe about it. Its tracks include Stackolee, Poor Ellen Smith, Wild Bill Jones, The Devil’s in ihe Girl and Hang Me, Oh, Hang Me – all of which I think are more or less guaranteed to appeal to anyone who likes this site.

The CD’s 1934 cover image was painted by Thomas Hart Benton, who played in a folk band with the young Jackson Pollock. That’s Pollock himself you can see playing harmonica in the sleeve’s foreground.

I’ve been listening to the CD all week, so I can confirm it’s a real good ‘un. Vic Smith, reviewing it for fRoots magazine, had this to say: “Another offering from the superb grouping of Dave Arthur, Pete Cooper and Dan Stewart. Each release brings a new development and this time we can hear a tighter sound and a more up-tempo approach to the instrumentals.”

So, what are you waiting for? Here’s the question:

Send your answers to PlanetSlade, using the e-mail link here. Please remember to include not only your answer, but also your (real) name and your full postal address. Please use the subject line “June CD competition”.

PlanetSlade's decision will be final. I'll draw four correct entries at random from all those received by midnight on June 30 (London time), notify the winners by e-mail and get their CDs in the post next day. I won’t pass your contact details to anyone else, although I may use them to send you three or four PlanetSlade e-mails a year announcing new content on the site. If you’d rather I didn’t do that either, please just let me know.

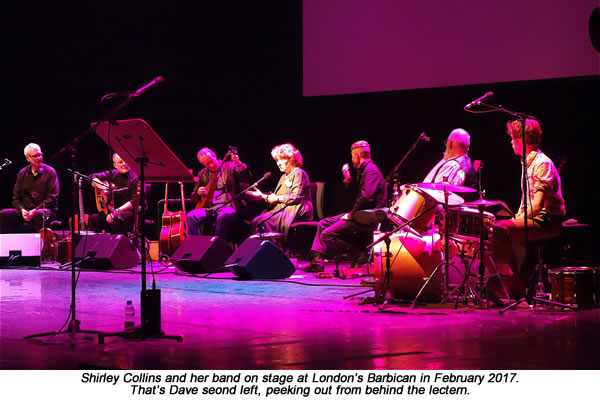

Dave’s had a busy year, recording music not only for his own album but also for Shirley Collins’ magnificent 2016 release Lodestar, where he plays guitar and banjo. He and Stovepipe’s Pete Cooper have been touring with Collins too, including a February 2017 gig at London’s Barbican where I went to see them myself. All this and he found time to play some songs at my 2016 Stagger Lee talk in Southwark too!

“Shirley has been a friend for fifty-odd years,” Dave told me in May. “She wanted people in the band that she feels comfortable with and are all supportive and put no pressure on her. It's been a fun few weeks: concerts all over the country at big venues, then main stage at Cambridge Folk Festival and main stage at the Green Man Festival. Then we finish for a while before a gig in Dublin.”

Catch them if you can – Shirley Collins with this band makes for a great evening.

Getting a Handel on John Cluer

April 18 brought an interesting letter from a Hertfordshire reader called Tammy Donoghue, who wrote to tell me about her 18th century ancestor John Cluer.

Cluer was the London printer who we think put the true murder story behind Pretty Polly into print for the first time. The suggestion, first put forward by the University of Washington’s David Fowler, is that Cluer met Charles Stewart, one of the killer’s shipmates, in a nearby dockside pub and got the story from him. His ballad sheet about it, titled The Gosport Tragedy in England, became Pretty Polly when that song migrated across the Atlantic.

Donoghue explains that Cluer began trading in his Bow Churchyard print shop in 1710, adding that by 1715, he was already acknowledged as a keen innovator in the printing of not just ballads, but also chapbooks, labels and shop signs. He was particularly interested in the music trade, she goes on.

“He wanted to print collections of music in a smaller pocket size version and started with operas,” Donoghue writes. “[This was] a very new and popular style that attracted Handel and, starting with Giulio Cesare in 1724, Cluer went on to publish a further nine of Handel's operas in pocket size. His pocket-size songbooks were the most successful ventures of their kind for many years. Imitators soon followed Cluer in this and other ideas, one of which was issuing songs on the back of playing cards.”

“Throughout the years 1720-1728, he was always on the lookout for new material, so it’s no surprise that he saw [Stewart’s tale] as a lucrative source of new material and another way to be a leader of innovation in music publishing.”

If Cluer really did get The Gosport Tragedy from Stewart, he most likely did so in the first few months of 1727. That would have given him very little time to enjoy the song’s success as, thanks to Donoghue’s letter, we now know he died in 1728, aged just 46. It’s nice to see that a humble ballad printer – generally thought to be a very lowly profession in Cluer’s day – could also make a significant contribution to popularising Handel’s music.

January 1, 2017. Graham Stewart of Glasgow writes:

“I’m writing a book on the history of broadcasting in Scotland and I’ve just been reading your article about the Ronald Knox incident.

“In that article you mention the number of complaints there were, saying: ‘Reith's figures show 2,307 appreciations for the programme, against only 249 criticisms, 194 of which were directed at Knox himself’. The reference you give is simply ‘BBC Archives’. Bit of a long shot perhaps, but you wouldn’t happen to have a note of the file number in which you found it, would you?

Paul Slade replies: Those figures come from a paragraph in BBC managing director John Reith’s report to the BBC board at their February 11, 1926 meeting, and the copy I have carries a handwritten note reading “(CO7/4)”. Whether that’s a BBC file number or not, I have no idea. I’m not even sure from the handwriting whether that second character is supposed to be a letter “O” or a zero.

I’m assuming the document I’ve got is the official minutes. The meeting covered a lot of different subjects, with just a couple of sentences devoted to the Knox affair.

January 10, 2107. Graham Stewart adds:

“Thanks, Paul. Yes, that’s a BBC file number alright!

“You may find the following paragraph I wrote of interest — it’s a very minor point, but the broadcast did not appear on all stations:

“‘On the basis that the Edinburgh studio received no more than half a dozen of those complaints, the Scotsman concluded that Scottish listeners had clearly understood and appreciated the humour to a greater extent than their English counterparts. However, this theory conveniently overlooks the fact that most Scottish listeners did not even hear the broadcast due to the Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee stations substituting their own local talks’.”

February 23, 2017. Phil Gray of Norwich in East Anglia writes:

“Two things: firstly, I was bought your book for Christmas and loved it. Made me want to write a murder ballad of my own (currently working on it…).

“Secondly, I thought you might be interested to know that my first album, Material Electrico, is available now. My artiste name is UnclePhil, and here’s a little video or two I put together for a couple of tracks from the album: I Only Eat in Places with Pictures of Food; (In) Honolulu.

“All the best, and more power to your writer’s elbow.”

February 24, 2017. Paul Slade replies: Thanks for that, Phil. I like your songs a lot: a nice raw, bluesy guitar tone and a quirky sense of humour too. That Pictures of Food chorus looks set to stay lodged in my head for quite a while.

Now that you’ve finished my book, may I suggest following it up with Dennis Covington’s Salvation on Sand Mountain. I’ve been doing a lot of train travel this past week, and that gave me a chance to really immerse myself in this fascinating volume. It’s Covington’s journalistic account of his time spent with snake-handling churches in the Deep South in the 1990s. It’s never cheap or mocking, never so shallow as to be touristy, and just a fantastic read. Full of strange wonders, and hugely enjoyable.

The book was recommended to me by The Victor Mourning’s Stephen Lee Canner, who took me to task for a glib reference to snake-handling churches and suggested I educate myself on the subject before casually shooting my mouth off about it again. He was dead right too.

Where to find my testimonials

The source sites for our latest collection of PlanetSlade blurbs can be found below. Sometimes there’s quite an interesting discussion attached.

Metafilter

http://projects.metafilter.com/5115/A-Cabinet-of-Curiosities

http://www.metafilter.com/contribute/activity/

God’s Jukebox

http://www.godsjukebox.com/NoirTrax/coon-creek-girls-pretty-polly/

J Nelson

http://j-nelson.net/2014/12/what-happened-to-longform-org/

Things

http://www.thingsmagazine.net/no-longer-leaving-the-building/

Mojo

http://ubb.mojo4music.com/