The real problem in this third verse comes later, though, when Dylan says she “got killed by a blow, lain slain by a cane”. No-one with Dylan's fondness for Biblical language could resist that neat pun on mankind's first murderer, but it's another line he may have found hard to defend in court. Lacking even the minimal wriggle room of the first verse's “killed with a cane” these words reinforce the impression that Carroll was beaten to death. Nowhere does Dylan mention the other factors involved.

The real problem in this third verse comes later, though, when Dylan says she “got killed by a blow, lain slain by a cane”. No-one with Dylan's fondness for Biblical language could resist that neat pun on mankind's first murderer, but it's another line he may have found hard to defend in court. Lacking even the minimal wriggle room of the first verse's “killed with a cane” these words reinforce the impression that Carroll was beaten to death. Nowhere does Dylan mention the other factors involved.

The final verse is really all rhetoric on Dylan's part, with very little factual content one way or the other. He does spell out Zantzinger's six-month sentence, the clear implication being that it was imposed for a murder conviction. This increases the apparent discrepancy between the seriousness of Zantzinger's crime and the light sentence he received, suggesting a much greater degree of corruption than even a cynical reading of the facts could support. Arguably, it implies that Zantzinger and his family were guilty of perverting the course of justice too.

Looked at as a whole, the song tells listeners that Zantzinger killed Carroll by beating her with his cane, and was charged with first-degree murder as a result. He's presented as a rich, spoilt brat, who behaved brutally towards an innocent kitchen maid, and felt no remorse when his actions led to her death. Corruption in Baltimore's police and court system, we're told, coupled with his family connections, ensured he was immediately bailed out of jail and given a ridiculously light sentence. There's all sorts of holes a competent libel lawyer could pick in that account, but by far the most serious is the false allegation of first-degree murder.

Heylin is sceptical about the excuses sometimes made for Dylan here, pointing out that any initial anger he might have felt at reading Wood's article must long since have faded by the time he wrote the song. “Reading this article made Dylan's blood boil with so much righteous fury that six months later he got around to lashing out,” Heylin writes. “One thing is certain - he hadn't spent the intervening months researching the case, or even keeping abreast of developments.”

Sounes is kinder, crediting Dylan with “the economy of a news reporter”. That's true enough, but any reporter taking Dylan's story to his editor would have got a severe bollocking for being so careless. If the story had been allowed into print without his errors being corrected, the paper employing him would have been forced into either printing a very embarrassing correction or coughing up a big out-of-court settlement to make the case go away. (26)

Their only chance of successfully defending Dylan's account in court would have been to argue that, by October 1963, Zantzinger had already received so much bad publicity that he had no reputation left to defend. Even if that had worked - which is pretty doubtful - Dylan the reporter would certainly have been sacked. The last words ringing in his ears as he cleared his desk would have been the editor's forceful reminder that he'd even spelt the killer's name wrong!

It's this last discrepancy which is most puzzling of all. Inventing a diamond ring for Zantzinger's finger quickly conveys the information that he had money, and exaggerating the charge against him does at least make the song more dramatic. But what possible purpose could be served by mis-spelling his name? Ian Frazier, writing in Mother Jones magazine, suggests the missing “t” is a deliberate signal of Dylan's contempt for Zantzinger, or done to emphasise the buzzing hiss of two closely-spaced Zs, but both those arguments sound pretty far-fetched to me.

What we do know is that the Wood story and the New York Times report Dylan was working from both spell Zantzinger's name correctly, with the “t” in place, as does every other newspaper story I've seen from that time. The first official version we have of Dylan's lyrics, which appear in typewritten form on the front page of Broadside's April 1964 edition, spells it correctly too. And yet, in every version I've ever heard, from its first studio recording in 1963, through the Rolling Thunder Review's 1975 performance to a 2006 Arizona bootleg, Dylan sings “Zanzinger”. That's also the way it's written on the lyrics page of his own official website.

Did Dylan always have the name spelt this way, only to find a helpful Broadside staffer correcting it for him before publication? Was it a simple typing error on his part which no-one noticed until the record was already out? Did he imagine that mis-spelling Zantzinger's name would confer some magical defence against any legal action the song might prompt? Was “Zanzinger” simply easier to pronounce when singing?

Whatever the answer, Dylan has now performed Hattie Carroll so often that I doubt he could sing “Zantzinger” even if he wanted to. He's toured in 37 of the 47 years since writing the song, and played it live on stage in all but five of those touring years. Two years of that touring - 1979 and 1980 - were devoted to his Christian material alone, leaving just three years between 1963 and 2009 when he could have included Hattie Carroll in his live repertoire, but chose not to do so. He's played it live every single year since 1986, and included it on at least two official live albums. And every one a “Zanzinger”. (21)

However you spell his name, Zantzinger has very seldom spoken in public about Dylan. Sounes got one of his very few comments on the subject for his 2001 Dylan biography. “He's just like a scum of a bag of the earth,” Souness quotes a spluttering Zantzinger as saying. “I should have sued him and put him in jail”.

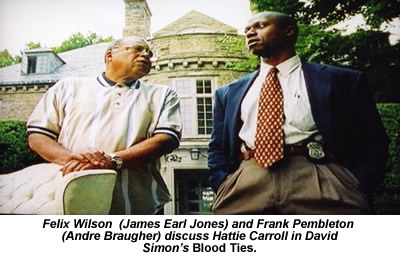

In the event, he never did sue over the song, and has never made any attempt to stop Dylan performing it in concert. But evidence emerging earlier this year suggests Zantzinger's lawyers did threaten action against both Dylan and his record label when the song was first released. Pleasingly enough, this evidence comes from David Simon, the writer and producer behind HBO's The Wire, a series which has made him the poet laureate of Baltimore crime.

Simon, then a crime reporter with The Baltimore Sun, spent 1988 shadowing the city's murder police for a book about their work which later inspired the TV show Homicide: Life on the Street. The access this gave him let Simon examine Carroll's old case file, where he found a surprising note. Intrigued, he made an appointment with Zantzinger and raised the issue face-to-face. His first problem was persuading Zantzinger to talk.

“I tried trashing Dylan,” Simon recalled 21 years later. “‘That son of a bitch libelled you. You could have sued his ass for what he did.’ Zantzinger smiled: ‘We were going to sue him big time. Scared that boy good!’ he said. ‘The song was a lie. Just a damned lie.’

“He enjoyed talking about how his lawyer had fired shots across Dylan's bow. Columbia Records was on the receiving end as well, Zantzinger said, adding that he dropped the idea of a lawsuit because, after being convicted of manslaughter and assault, he'd seen enough of courtrooms and controversy.

“I told Zantzinger about a note I had found in the old homicide file: ‘Attached is correspondence from... a folksinger in New York who seeks information about the aforementioned case, which was investigated by your agency’. But Dylan's letter wasn't attached - snatched, perhaps as a souvenir from police files. But the cover sheet, dated months after the release of Hattie Carroll, was telling. Dylan was apparently writing too late to improve his song's accuracy; his letter was the re-action of a worried young man. Zantzinger enjoyed that immensely.” (28)