As Jackson and Walling's last appeals dribbled through the system, preparations to hang them were already well underway in Newport.

As Jackson and Walling's last appeals dribbled through the system, preparations to hang them were already well underway in Newport.

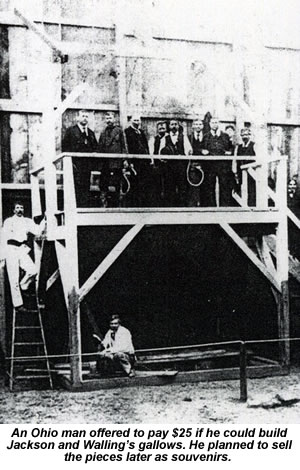

The Pearl Bryan souvenir trade was gearing up again too. One Ohio carpenter hit on a novel angle, when he offered to build the new gallows platform Newport needed for the hanging. Far from charging for this work, he offered to pay $25 just for the privilege of being allowed to carry it out. His only conditions were that the wood he used for the platform must remain his property, and that he'd be free to demolish the gallows and take it all away again immediately afterwards. His plan, it emerged, was to saw this up into short lengths and sell each piece as a unique souvenir of the hanging. (47)

No doubt he'd have found a ready market, but Newport council vetoed the scheme and gave the gallows contract to a local carpenter called Horace Allen instead. Excitement about the hanging was so great that even Allen's Weingartner Mill workshop was besieged by curious crowds who hoped to glimpse the scaffold he was working on there.

There hadn't been a hanging in the Cincinnati area for over 12 years, and this seems to be the first one Sheriff Plummer ever had to organise. He knew it would be his job to pull the lever opening the traps beneath Jackson and Walling's feet when the fatal hour came round, but faced this prospect with great trepidation. He insisted that his old friend Dr Carothers must stand by him on the platform in case he found himself overcome at the crucial moment. More than anything, he dreaded having to go through the whole ordeal twice, so he told Allen to build a mechanism that could open both traps with a single pull of one central lever.

Despite his fears, Plummer was determined to see the responsibility through. "One must not shrink from his duty, however unpleasant it may be," he told the Kentucky Post. (48)

On the morning of March 19, Jackson and Walling said goodbye to their mothers at Alexandria and boarded the carriage that would take them to Newport Jail for the last night of their lives. When they arrived, they found the tiny jailhouse was already throbbing with activity. "Crowds milled about the small structure," Doran writes. "A company of the Kentucky National Guard was sent to guard the place, and hosts of special deputies were sworn in to maintain order.

"When they were led to their cell, the two men smoked in silence. Occasionally, they walked to the window and glanced at the gaping crowds, waving to friends whom they recognised. As the day drew to a close and the men watched the sun sink for the last time, they became increasingly nervous."

Plummer stopped by the cell at about 7:00pm to ask if either man had a statement he wished to make, but both declined. They passed the evening singing hymns with a guard called Billy Sutton. "Jackson's tenor and Walling's deep bass rolled forth in Au Revoir and A Mother's Appeal To Her Boy for the edification of the throngs that stayed about the place all through the night," Doran writes. Other accounts tell us that Jackson deliberately sung out of his window to entertain the people outside. "An awful silence settled on the crowd as Jackson sang, and he apparently felt enjoyment in the sensation he was creating," one unidentified news clipping says.

The two men broke off their impromptu concert at midnight to eat a meal of hamburger steak and onions. "They'll make you sleep," Jackson said approvingly. They were then given a couple of after-dinner cigars and sat smoking them as they calmly chatted. At around 1:30am, Walling retired for the night, but Jackson decided to stay up a little longer. All around them, preparations for the hanging were still going on.

Sheriff Plummer arrived at Newport's courthouse yard, where the gallows was now being tested, at about 1:40am to deliver the restraining straps and black hoods he'd need later, then crossed the street to his prisoners' cells. He found Jackson still awake there, and asked him if he planned to make any final statements on the scaffold before Plummer pulled the lever. If he'd hoped Jackson might yet give Walling a last-minute reprieve by finally confessing to the murder himself, that hope was soon extinguished. "I don't think I will have any to make," Jackson replied. Plummer told him to be ready at 7:00am for the hanging two hours later, and reminded Sutton to wake Walling in good time for the same appointment. (49)

Walling slept through the night, but Jackson managed no more than a fitful doze. He finally went to bed a little after 3:00am, but started and woke very frequently before rising again at 5:45am. An hour later, Walling was up too, and they ate a hearty breakfast of buckwheat cakes and coffee. By now two coffins had arrived in the courthouse yard. Walling's girlfriend sent him a message: "Die Game".

Sheriff Plummer finished instructing his deputies on their duties at about 7:15am, then took Jackson and Walling the new suits Kentucky had bought them to wear on the scaffold. Both men joked about the suits' poor fit as they changed. Reverend Lee arrived just after breakfast too, prayed with Jackson and Walling for a while, and then led them in singing God Be With You Till We Meet Again, Home Sweet Home and The Half Has Never Been Told. "Jackson glanced at the crowd outside the window," Kuhnheim says. "He set a chair up, stood on it, and began singing hymns to the crowd."