You'll already see Flo punching Andy as much as the other way round by this era of the strip, and a slow transfer of power between them begins. Here's a few of the key strips that mark it out:

You'll already see Flo punching Andy as much as the other way round by this era of the strip, and a slow transfer of power between them begins. Here's a few of the key strips that mark it out:

* Andy punches Flo, but then sees her working out with weights as he leaves for the pub. "One o' these days I'm goin' to 'ave trouble with that girl," he predicts. (1965)

* Flo tells the HP man what she's learned about beating Andy in a fight: "Lead with yer left, then belt 'im with yer right." (1969)

* Chalkie points out that it's taking Andy longer and longer to best Flo in a fight. "It's getting tough," he replies. "She's a stone heavier every year." (1971)

* Flo lands Andy a good one, knocking him clear out of their dustball fight and leaving him flat on the pavement. "Good f' you, Flo!" says Ruby. "Yer must be the 'appiest woman in the world now yer know 'ow to lay 'im out." (1971)

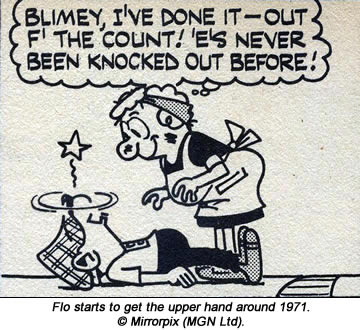

* Flo punches Andy out the front door and into the road. Grinning down at his unconscious form, she says: "Blimey - I've done it - out f' the count! 'E's never been knocked out before!" (1971)

* A dustball fight leaves Andy flat on the floor, but Flo still standing. "I'm sorry, sweet'eart," she says. "I'm heavier than you - that's what beat yer". (1972)

* Andy gets home drunk to find Flo with her dukes up waiting for a fight. "I'm no match for you any more Pet - look, I'm tremblin'," he says. The same thing happens again a few months later: "Please, Pet, not tonight, eh? I'm not up to it." (Both 1981)

* Andy is drunk, but scared to enter the house. We see him hiding behind the door jamb, watching nervously as Flo rolls up her sleeves to batter him. (1987)

Andy stages the odd rearguard action while all this is going on, but there's never any doubt which way the wind is blowing. More and more, what remains of his violence against Flo is implied rather than shown outright - a process which reached some kind of watershed in a 1973 collection.

This includes four cartoons which show Flo punching Andy and two dustball fights, both of which she wins. The worst Andy can manage is to chase Flo down the street, shout at her a couple of times and throw his dinner (inaccurately) at her head. The same collection is quite happy to show Andy punching Percy the rentman, the manager of his local dole office and a stranger in the pub, but Flo is now off-limits. (22)

Smythe reflects this new dynamic in the way he draws the couple. He'd always shown Andy as being slightly shorter than Flo, and has her referring to him as "that little whippet" as early as September 1960. As he started to refine the characters' appearance in the early sixties, rounding their figures into the denser, more compact forms we know today, he accentuated that height difference all the more, and often posed Andy and Flo nose-to-nose so readers couldn't miss it. (23)

Some see this as marking a shift in their relationship from husband and wife to mother and child, with Flo constantly struggling to keep her naughty offspring under control. In 1967, she's being questioned by a pollster on doorstep, who asks if she has any children. Spotting Andy approaching down the street, happily bouncing his football along beside him, Flo replies: "Just the one". By 1974, Andy is meekly asking Flo for a raise in his "pocket money".

"I like Andy being shorter," Goldsmith says. "I think it's funnier. I don't quite see him as a child, though - maybe a naughty teenager." Roger Mahoney, who now draws the strip, adds: "Flo is mature and down-to-earth, whereas Andy has never really grown up mentally." (11)

"Flo is the responsible one," Hiley agrees. "She knows what should be done and tries to do it. Whereas, he knows what should be done and tries to avoid it. Like a lot of couples all of us know, it's difficult to figure out why it works, but it does work. They seem to take refuge in each other for some reason. She needs a man, and he needs someone to rescue him when he needs rescuing."

In one sense, Andy rescues Flo too - if only from boredom. In 1973, Smythe responded to readers who asked him why she didn't simply leave the rotten little sod. "Flo sometimes reaches the bus shelter and studies the timetable," he writes. "But where would she go? Some crummy little bed-sit in the next town? No, Flo's got too much sense for that. She tried it once, and it wasn't much fun. She knows she needs Andy - warts and all. Needs him to worry over, complain about, nag at and laugh with."

Returning to the same subject in 1977, he adds: "Flo seems to enjoy the occasional dust-up with Andy. Loves a good argument. Thinks there's no fun in being given her own way - she wants to fight for it." (24)

Trevor Peacock came to the same conclusion when writing Andy's 1982 musical. "In the play, Florrie leaves home and goes away," he tells Lilley. "And while she's away, she's in a state of misery. You see, it's this terrible little bloke she lives with - she hasn't got him any more. And Andy is in a terrible state as well - there's washing-up all over the place, and he's fed up. Then it strikes you - of course! He adores her. He totally depends on her. His life is locked into hers and hers to his."

And that's what Keith Waterhouse thought too. "The curious thing about Andy and Flo is that it takes no effort to see they are genuinely fond of each other," he said after completing his scripts for Andy's 1988 TV series. "They are, in fact, made for each other. That came out in the TV performances. The two characters were very touching together."

Paula Tilbrook, who played Flo in the show adds: "I think Flo puts up with Andy partly through habit and partly because, in spite of all his faults, she does love him. She gives as good as she gets from him. If it was any different, I think she'd be terribly bored." (25)

Smythe continued the dustball fights between Andy and Flo right through to his death in 1998. We see Andy threaten Flo by words alone many times in Smythe's final 20 years, but very few signs that he's actually hit her. For every panel depicting Andy-on-Flo violence - I've found just three between 1976 and 1990 - there are a dozen that show Flo punching Andy off his feet.

Since Smythe died, their once-turbulent relationship has been toned down still further. The Kettle/Mahoney strips, which ran from 1998 till 2011, would occasionally show Flo punching Andy out the front door but no other violence between them. In their own scripts for Mahoney, Goldsmith and Garnett have restored the dustball fights Kettle avoided, but otherwise keep the violence under control. Even when it's Flo attacking Andy, things never escalate beyond a slapstick sequence showing her hurling her kitchen pans at him - and generally missing.

"In the early days, up to the mid-sixties, Andy could be quite an unpleasant character with the domestic violence," Goldsmith says. "People still refer to Andy like that, but he hasn't actually been that way for over 30 years."

It's clear enough why Smythe felt the need to soften Andy's initial thuggish personality, and that decision has been paying dividends for the strip ever since. A more intriguing question is whether he had a real-life model in mind for Andy the drunken, workshy wastrel when he created the character in 1957. To answer that, we must travel back to Hartlepool at the time of the First World War. It's time to meet Reg Smythe's dad.

Richard Smyth married Florrie Pearce at the Congregationalist Chapel in Hartlepool on December 23, 1916. They'd met less than a year earlier, but Richard had managed to get Florrie pregnant almost immediately, and she was already carrying Reg when she walked up the aisle for what The Sunderland Echo later confirmed was a shotgun wedding. Richard at the time was 23, and his bride just 19. (26)

Florrie's last job that day before changing into her wedding dress had been black-leading the fire grate at home so the room was spick and span for the reception guests they were expecting later. Everything we need to imagine about working class life in Hartlepool at the time - the pride as well as the poverty - is there in that single image: a bride-to-be, black-leading the grate on her wedding day.

The First World War was then in its third year, and Hartlepool's status as a major ship-building town made it a target for the German Navy. In just a single night of December 1914, the Kaiser's ships had rained 1,150 shells on the town, killing 117 residents and causing the first military fatality on British soil since the English Civil War. It was only the fact that Richard was a shipwright - then a reserved occupation - which allowed him escape military service and a spell in the trenches.

Richard's father had been a ship's plater, and Florrie's father an engine fitter, so they both came from very similar stock. But the Smyth family had been Congregationalists since the 1800s - "Independent Chapel" as the locals called them - and Florrie often felt that they resented Richard's decision to marry outside that faith.

Reg was born on July 10, 1917, and the new baby encouraged the two clans to make peace. "The Pearce and Smyth families would get together and celebrate at one of the many local pubs," Ian Smyth Herdman says in his family memoir. "Even though times were hard and the First World War prevailed, this family group needed little encouragement to celebrate." (27)

At the beginning of 1918, Richard found work in Sunderland, about 17 miles up the coast from Hartlepool, again building boats for the war effort. Florrie and Reg moved there with him for a few years, and the new job gave them slightly more cash, but already the couple was fighting. Richard took to spending what little money they had on drink, and nothing Florrie did seemed able to stop him. "She would stand outside with baby Reg swaddled in a blanket," Smyth Herdman says. "As Richard left the pub, Florrie would shout abuse."

When Richard's mother Priscilla and his sister came to visit, they would sometimes take Reg back to Hartlepool with them so he could have a few weeks shielded from the conflict at home. "Reg was spending more time with his aunts and uncles than with his own parents," says Smyth Herdman.

The end of the war in 1918 put a stop to the North East's ship-building boom, and from that point on Richard was often out of work. Lily, Reg's sister, was born in 1919, which added another mouth for the family to feed.

Many other local families were struggling too, as Reg discovered when he started his education at Hartlepool's Galleys Field School. "There were working class kids who wore shoes to school and then, moving down, there were those who wore boots," he tells Lilley. "Then came the canvas shoe wearers, followed by the bare foot brigade. Finally, the anonymous, invisible mass at the very bottom of the heap who didn't go to school at all."