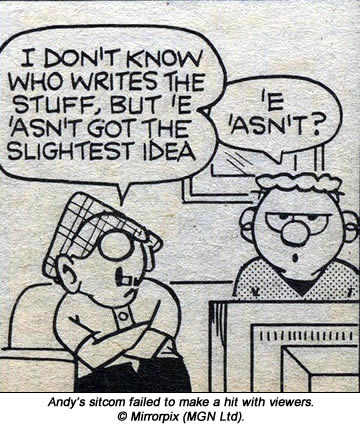

Sadly, back in 1988, not enough viewers agreed. Despite being launched with the fanfare of a TV Times cover, the show lost about a third of its viewers during the six-week run, and was never granted the second series everyone involved had hoped for. "I loved doing it so much," Bolam says. "I was really looking forward to doing the next series."

Sadly, back in 1988, not enough viewers agreed. Despite being launched with the fanfare of a TV Times cover, the show lost about a third of its viewers during the six-week run, and was never granted the second series everyone involved had hoped for. "I loved doing it so much," Bolam says. "I was really looking forward to doing the next series."

What no-one could agree on in the post-mortems was whether the series' mistake has been making Andy too nasty or not nearly nasty enough.

Waterhouse had taken an early decision to avoid of any suggestion of Andy as a wife-beater in the show, and limit what violence it did contain to strictly cartoon forms. "It doesn't do any lasting damage when Flo clonks Andy with her rolling pin." he writes in the Mirror's tie-in book. "And when Percy the rent collector sustains a black eye for pestering Andy about the arrears, it's miraculously gone when he turns up in the Boilermaker's Arms a few minutes later."

Gilbert and Davies had both endorsed that decision at the time, but for Alan Coren in The Mail On Sunday, the result was a show that both sugar-coated Andy and robbed him of his edge. "James Bolam as Andy is a delight," Coren writes. "Which, sadly, brings us to the flaw. The truth is, Andy shouldn't delight at all, he should enrage. Andy Capp has become the victim of the grotesques with whom his life teems - not, as he is in the original cartoon, their scourge. We end up hating the wrong people." (81)

"If you make him lovable, then he's accessible," Davies sighs in response to this criticism. "And if you make him unlovable, then people won't watch the programme. It's a very difficult balance to get right."

As it is, the series fell between the two stools of making a show palatable enough to attract the mass-market audience which Thames' investment demanded, and finding the cult viewers who might have appreciated its more stylised elements. It deserved a better fate, so let's hope the DVD release prompts people to take a second look.

Smythe was philosophical about Andy's adventures in other media, though he did confess that he'd occasionally felt frustrated when taking ideas to the two projects' directors. "They would listen patiently, then say 'Okay, you've been consulted and we know how you feel,' then hurry away and do nothing about my suggestion," he tells Lilley.

"I felt I could have offered a little more than I did, but at the same time, I know there are horses for courses, and that a theatrical or TV director is more expert at his particular craft than I could ever be. I wouldn't expect a writer or director to try and write or draw my strip, so why should I expect to be able to do his job for him or make the sort of decisions he has to make?" (82)

Waterhouse had certainly taken the view that writing the TV scripts was his job, and that there was nothing to be gained by inviting Smythe to second-guess him at every turn. "I didn't exchange a word with Reg," he says. "I thought, and I'm sure he would agree, this was the best way of doing it."

By the time the TV series was screened, Smythe was 71 and nearing the end of his latest five-year contract with the Mirror. Lilley asked if he has any plans to retire.

"Why the heck should I stop working?" Smythe replies. "My health is pretty good, and I have a whole year's supply of strips on hand in case I should want to take time out for any reason at all. But truth to tell, I want to carry on because I wouldn't know what to do if I stopped. I couldn't be idle. I'd still be drawing cartoons, and they might as well be cartoons of Andy Capp - they pay better."

That year's stockpile of strips was Smythe's answer to the Mirror's request that he start grooming a successor to take over Andy after his death. He could never bring himself to relinquish even that degree of personal control over the strip, so instead he used his remarkable energy and determination to continue producing as many as six new Andy strips a day. "Even towards the end of his life, he would sit in a room he called 'the den', sketching away from 9am often till 2am next day," says the BCA website.

For Smythe, it was still Andy and Flo's small domestic struggles that gave the strip its fascination. Andy's slapstick antics in the pub may be what pulled readers in, but it was his scenes at home with Flo that kept them coming back for more. "When characters are as deeply-felt and understood as Andy and Florrie, ideas aren't all that difficult to come by," he says. "I suppose the strip will continue to be interesting for as long as people go on fighting and arguing about things. It certainly hasn't got stale so far."

Smythe's one concession to the increasing years was his decision to give up smoking, which came in 1983. Andy followed suit soon after, with a strip from around August 1985 showing him with a fag in his mouth for the last time. A January 1986 strip has Flo congratulating him for giving up the habit. (83, 84)

"Andy had to stop smoking," one journalist quotes Smythe as saying. "Too many kids read the cartoon, and it was time to set a better example." Turning to his own decision to give up the weed, Smythe adds: "I doubt Andy would have stopped on his own." Health groups such as ASH (Action on Smoking & Health) declared themselves delighted at the move, but Smythe was quick to reassure fans that all Andy's other bad habits remained firmly in place. (85)

Even in his seventies, Smythe still found plenty of battles to fight in protecting the strip's integrity. A 1989 Department of Health campaign using Andy was allowed through the net, but he put his foot down when the advertising agency J Walter Thompson suggested removing Andy's cap for a campaign promoting Tyneside as a business destination.

The resulting row was lively enough to make news on both sides of the Atlantic. "The concept involved a series of drawings showing Andy gradually sprucing up, throwing away his cap, putting on a suit and tie and brushing his hair," Sheila Rule writes in The New York Times. "The drawings' captions explained that, in the past 30 years, no city had changed as much as Newcastle." (86)

As soon as Smythe heard of the campaign's plans, he let it be known that he didn't think much of the idea. "That would be like Groucho without his moustache, the Lone Ranger without his mask or Beetle Bailey without his helmet." He told reporters. "I couldn't believe anybody could be so stupid." Papers like The Northern Echo fell on his remarks with glee, producing such headlines as: "No Slicked Back Capp"; "Yuppie Andy Gets The Boot' and "Dunce's Capp For The Ad Men".

Whether the campaign's managers had hoped Smythe himself would draw the ads, I don't know. Even if they'd been able to persuade the Mirror to let them use Andy without his permission, though, they had decades of evidence that no other artist could quite get the character right, and in the end Smythe's veto was enough to scupper the whole idea.

"Smythe, 72, does not own the copyright in the cartoon strip," Rule writes. "He signed it over to the Daily Mirror when he first started drawing Andy. But he believes the wide syndication gives him 'weight and authority'. Simon Burridge, an executive at the agency, said the Andy Capp concept was effectively dead because Smythe 'doesn't want anyone taking the cap off'."

The next big battle came in January 1997, just 12 months after Piers Morgan had taken over as the Mirror's editor. That year's biggest stars for the UK tabloids were The Spice Girls, and Morgan decided a cartoon strip starring a similar "girl power" character was just what the Mirror needed. She would be, he announced, "a mischievous ladette daughter of miserable old Andy".

The mystery here is why Morgan - or anyone else on the Mirror for that matter - thought that linking the new character to Andy would be anything other than a liability with the Spice Girls fans she was supposed to attract. As sometimes happened with his commercial campaigns, though, Andy's sheer fame seemed to trump all other concerns, and the idea was pushed forward regardless. (87)

"Brendon Parsons, the then deputy editor, wanted Reg Smythe to create Mandy Capp, daughter of Andy," Layson tells Hagerty. "Reg had a fit. Well, it just didn't go with his image, and everybody knew that he and Florrie had no children. But Parsons insisted, so I got Roger Mahoney to draw it and Carla Ostrer to write the stories and dialogue. Soon, it replaced Andy as the strip at the top of the page, which really upset Reg."

Mandy's debut strip appeared in the Mirror of January 6, 1997, together with some promotional copy. "She's sexy, sassy and independent," the blurb announces. "She's a Nineties woman with a job, a young child and a string of adoring men. She's Mandy Capp, a young, hip, female version of the Mirror's famous cartoon character Andy Capp."

The contrast between Mandy's shallow roots in the Spice Girls craze and Andy's deep grounding in his creator's troubled childhood could hardly be greater. Smythe refused to acknowledge Mandy even existed, Andy was never allowed to visit her strip, and soon she was following the same trajectory Buster had taken 37 years earlier. First the Capp surname was dropped from her strip, then all suggestion of a family relationship was quietly forgotten.

She didn't retain her position at the top of the page for long either and, although she still appears in the Mirror every day, it's now as the fourth of its sixth strips - and Andy's back at the top where he belongs.

Both these run-ins show just what a strong hold Smythe's unique status as Andy's creator still gave him over how the character was handled. By 1997, though, even he couldn't deny that his health was beginning to fade. Goldsmith, who was working on the cartoon page's production desk by that time, believes the strip was starting to suffer. (88)

"Piers Morgan was actually going to cancel Andy Capp towards the end of Reg Smythe's life," Goldsmith says. "When he was in ill health, he was struggling. The standard fell off dramatically. Piers Morgan really hated it, and said to Ken Layson, 'I want to cancel this strip and put something else in there - something modern'."

Layson was able to fight off that suggestion by replacing the odd sub-par strip with one from Smythe's stockpile, but very soon matters were taken out of his hands.

The beginning of the end came on May 6, 1997, when Reg's wife Vera died at the age of 80. "Vera died and Smythe's long-time girlfriend, Jean, whom Vera had known about, moved in with him," Layson tells Hagerty. A year later, Reg and Jean married in a private ceremony at the White Gates bungalow. And a few weeks after that, Smythe himself died, succumbing to lung cancer on June 13, 1998, aged 81.