Reg himself belonged to the canvas shoes group, spared the indignity of slipping any lower only by a sixpenny pair of Woolworth's plimsolls. "My family was just about getting by," he says. "We lived on lard - dripping. Dripping was OK for fried bread. It was also very useful for greasing your bike [and] great for putting on your hair!"

Reg himself belonged to the canvas shoes group, spared the indignity of slipping any lower only by a sixpenny pair of Woolworth's plimsolls. "My family was just about getting by," he says. "We lived on lard - dripping. Dripping was OK for fried bread. It was also very useful for greasing your bike [and] great for putting on your hair!"

The young Reg enjoyed drawing at school, and a teacher called George Carter evidently spotted some nascent talent in the lad. He encouraged Reg to go out and practice his skills by drawing St Hilda's, Hartlepool's 12th Century church, and other prominent buildings in the town. "I quite liked drawing when I was at school, but I certainly wasn't obsessed by it," Smythe says. "Usually, I was about fourth or fifth in the class when examination time came around and we were told to draw that obligatory bunch of tulips in a jam jar."

Richard and Florrie's marriage continued up and down for the next few years until Florrie produced a pair of twins in 1924, who lived for less than a year. The heartbreak caused by this kicked their rows up to a whole new level, and Florrie moved out of the Sunderland house. By 1926, both she and Richard were back in Hartlepool, though now married in name only. Reg and Lily spent most of their time with their grandparents on the Smyth side of the family, who were now more suspicious of Florrie than ever.

Richard managed to find a job down south for a while, working in a Surrey boatyard and sending what money he could back home. He was amazed at how prosperous the South East seemed compared to what he knew. "It is quite a change building boats here," he wrote in one excited letter. "No oars at all, just motor boats!"

Meanwhile, Florrie had taken an evening job as a singing barmaid in one of Hartlepool's many pubs. She had to look her best for that, but could not afford to visit the hairdresser every day. Instead, she took to curling her own hair, leaving the curlers there, and covering them with a headscarf until it was time to go to work. This meant she'd be walking around in curlers and a turban-like headscarf all day, which led Richard's side of the family to nickname her "The Turk".

That's how she would have been dressed for one family row which Smyth Herdman relates. Reg was at his grandparent's house watching, when - according to Smyth Herdman's account - Florrie turned up determined to pick a fight. Hearing that she was on her way, and knowing this promised an entertaining spectacle, the neighbours up and down Alliance Street positioned themselves in windows and doorways to enjoy the show. Public rows between Florrie and Reg's grandparents James and Priscilla were a pretty regular event by then, but the procedure was always the same.

"Reg's grandparents were terrified of the trouble Florrie caused, and often grandmother would hide behind grandfather when he answered the door," Smyth Herdman says. "Grandmother was terrified of Florrie's outbursts, and further mortified when she saw everybody in the street watching. During the arguing, she would pluck up courage. Stepping from behind grandfather, she would lose her temper and send Florrie packing with a flea in her ear.

"After the debacle, poor grandfather would have to sit down, and he needed a jug of ale to recover from being shown up in the street. Surely this must have been traumatic for the young Reg, and would no doubt be remembered and sketched into his Andy Capp cartoons in later life."

Reg turned 14 - then the minimum school leaving age - in 1931, entering the job market just as the Great Depression was reaching its peak. He got work as a delivery boy in Charlie Walker's Hartlepool butcher's shop - work he was pleased to have - but found the shop's weekly "slaughtering day" hard to bear. In those days, butchers would slaughter beasts themselves, usually in an out-building close to the shop. In Charlie Walker's case, this task was carried out every Wednesday afternoon, and handled by his formidable wife Annie.

"The slaughterhouse was behind the shop, and there was a metal ring embedded in its floor," Lilley explains. "An animal would be tethered to this, and its head pulled down in preparation for the kill by means of a rope passed through a ring in its nose. The slaughtering of the beasts was done by the woman who owned the shop - a huge, muscular female who frightened the life out of the little lad. She killed animals by hitting them accurately between the eyes with a great bloody spike."

Reg was sacked from the butchers' shop job two years later, as his coming 16th birthday would otherwise have meant the Walkers had to buy him a ninepenny National Insurance stamp every week, and they preferred to replace him with another 14 year old instead. In 1933, still just 16 years old, he joined his father - along with half of Hartlepool's other menfolk - on the dole.

Two years of aimless mooching about followed, then Reg turned 18 and announced he was going to join the army. His father called round to say goodbye on the day Reg was due to leave for his Cairo training with the Northumberland Fusiliers.

"My father was an Andy, cap and all," Smythe wrote in 1965. "Well, maybe not quite an Andy. Like some of us, he might do the same things, but not with Andy's poise. He took me down to the Snooker Room, loser pays. The last words I can remember him saying were, 'Take care o' yerself, lad. We haven't seen much of each other - pink in the corner pocket.' I paid. I never saw him again."

Twenty-five years later, describing his dad to Lilley, Smythe adds: "He mouldered his life away. The only real difference between him and me was that I said 'Bugger it!' and joined the army."

It's pretty clear, then, that all the building blocks for Andy and Flo were already there in Smythe's mind by the time he left for Cairo in 1936. He gave Flo his mother's Christian name, her maiden name, her feisty attitude and her curlers-plus-headscarf combo. Like the terrifying Annie, Flo would soon show herself capable of taking on any man. Andy got Richard's boozy ways, his long periods out of work and his love of both snooker and gambling - plus his cap, of course.

"Andy is perfectly content to lay about," Smythe told the Saturday Evening Post in 1973. "He is a proud, able-bodied Englishman who considers welfare his due, even his duty. It's not a bad life. My father lived on welfare till the day he died, respected to the end by his family and his community. And do did I until I was 18." (28)

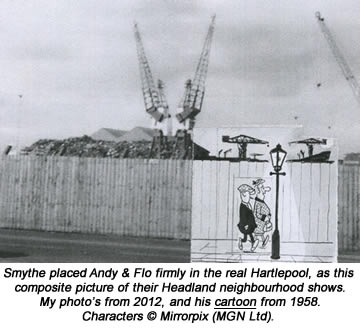

Andy and Flo, like Richard and Florrie, would always be fighting, and Smythe gave them the same house at 37 Durham Street, Hartlepool, which his mother lived in after the separation. In one 1975 collection, Smythe describes his fictional couple's street in terms which suggest he's really recalling his own childhood there: "Little terraced houses with an outside loo, one cold tap in the back kitchen where the walls are always wet, with windows that won't open and doors that won't close, and those freezing cold bedrooms where your breath comes out like a cloud of smoke." (29, 30)

The Hartlepool streets he drew as Andy and Flo's neighbourhood have the same real-life landmarks Richard and Florrie saw every day, including St Mary's Church in Durham Street, the breakwater Andy uses for fishing and the Headland's railed walkway looking out over the North Sea. As in real life, one of the couple is Independent Chapel and one is not - although Smythe gives this faith to Flo rather than Andy to make a particular gag work.

Smythe's mum would sometimes give interviews after the strip became a success, and was always happy to confirm that Andy and Flo's constant ructions and reconciliations were based on her own stormy relationship with Richard. But she never failed to point out that there was one important difference too. "Unlike Andy, my husband was never an aggressive man," she told a journalist in 1976. 'But, my goodness, although he didn't like work, he was certainly fond of a pint of beer and a flutter on the horses!" (31)

When Smythe joined the British Army in 1936, he did so for what was known as "seven and five": that is to say, seven years of active service, followed by five more years as an army reserve. What he didn't know was that the Second World War was just three years away, and that this would stretch his seven years of active service to nearly ten.

Things started well enough with his Cairo posting, though, at least as far as his pre-war service there was concerned. "We used to do our training in the morning because of the heat," he tells Lilley. "After lunch, the rest of the day was your own. I used to play tennis quite a bit."

The system then was that each man would spend the first four years of his active service abroad, then be shipped home to the UK for the remaining three. Homesick soldiers knew that, when the time came to return to Blightly, they'd be allowed just one kitbag and one suitcase for all their belongings. Many bought these suitcases months ahead of time, packing and repacking them to make the glorious day seem a little closer.

Smythe saw an opportunity there, using the artistic skills he'd displayed at school to set up a small business inking each soldier's initials on to his case in careful italic script. He'd taken to including little cartoon sketches in his letters home too, and soon became known throughout his unit as the bloke who could draw.

When war broke out in 1939, Smythe became a machine gunner and saw action both at the siege of Tobruk and in the El Alamein campaign. He rose to the rank of sergeant and came home with campaign medals for both Palestine and North Africa. He had no home leave during his entire ten years abroad - not even when his father died in 1940 - but only a few spells of R&R in Cairo.

It's typical of Smythe's modesty that he would describe this period as nothing more than "the Northumberland Fusiliers and the German troops [chasing] one another up and down the Western Desert". And yet, as Smyth Herdman points out, Smythe would also rate these army years as one of the biggest influences in his life.

He gave Andy precisely this wartime experience too, establishing in various strips that Andy had driven a Bren carrier in North Africa, that he'd been a sergeant in the Northumberland Fusiliers, that he'd fought in the same battles as Smythe himself, and come home with medals on his chest. Andy never forgot his army years any more than Smythe did, and was still calling himself "an ex-soldier" as late as 1990. " (32-37)