Even before the bubonic plague outbreak of 1603, St Saviour's parish graveyards were full to bursting. "The air must often have been reeking with pestilential vapours," William Rendle writes in his 1878 book Old Southwark & its People. "One churchyard is filled, another spot close at hand is taken in and filled in its turn and so on, until the dead gradually become too many for the living. In 1573, the churchyard is enclosed with a substantial pale. 1594, 'the new churchyard'. 1620, 'the churchyard within the chain gate'. The vestry seems often to be looking about for burial places." (103)

Even before the bubonic plague outbreak of 1603, St Saviour's parish graveyards were full to bursting. "The air must often have been reeking with pestilential vapours," William Rendle writes in his 1878 book Old Southwark & its People. "One churchyard is filled, another spot close at hand is taken in and filled in its turn and so on, until the dead gradually become too many for the living. In 1573, the churchyard is enclosed with a substantial pale. 1594, 'the new churchyard'. 1620, 'the churchyard within the chain gate'. The vestry seems often to be looking about for burial places." (103)

The place names Rendle puts in quotation marks there are taken verbatim from the minutes of St Saviour's 16th and 17th century vestry meetings and some think 1594's "new churchyard" was the site we now call Cross Bones. That's certainly the phrase used to describe it in an August 1760 lease from the Bishop of Winchester granting one Edward Pearson access to "a place called the New Churchyard and situate in or near Red Cross Street in the parish of St Saviour, Southwark". It's by no means certain that the lease's new churchyard and Rendle's churchyard were the same place, but Pearson's document does confirm that Cross Bones was still owned by the Bishop of Winchester as late as 1760, and that's quite useful to know in itself. (104)

Our first reliable glimpse of Cross Bones in the historical record comes in John Stow's 1598 Survey of London. I've already quoted from Stow's description once at the top of this piece, but it bears repeating here. He mentions the 12 stewhouses dominating Bankside after 1506, then says:

"I have heard ancient men of good credit report that these single women were forbidden the rites of the church, so long as they continued their sinful life and were excluded from Christian burial if they were not reconciled before their death. And therefore, there was a plot of ground, called the single woman's churchyard, appointed for them far from the parish church." (105-107)

Like everyone else who's studied Cross Bones' history, the MoL believes it's our Redcross Way site Stow has in mind here. That conclusion's supported by both 1795's Histories and Antiquities of the Parish of St Saviour's Southwark and by 1833's Annals of St Mary Overie. "We are very much inclined to believe this was the spot," the first volume's authors write. "We find no other place answering the description given of a ground appropriated as a burial place for these women; circumstances therefore justify the supposition of this being the place." The Annals are even more unequivocal, saying: "There is an unconsecrated burial ground known as 'the Cross Bones' at the corner of Redcross Street, formerly called the Single Women's burial ground". (108)

It's fair to conclude from all this that Cross Bones was already in use as a burial ground by 1598, when Stow produced his survey, and that it was old enough even then for only "ancient men of good credit" to remember its beginnings. That seems to rule out 1594 as the date for the first burials of all there, though it may mark the date St Saviour's Parish first took an interest in the site. Even by 1613, it was still not listed as an official parish burial ground, as we can see from a price list of burial costs St Saviour's published in that year. This mentions only the churchyard surrounding St Saviour's itself (now Southwark Cathedral) and the College Churchyard on Park Street. The tariff includes a note that pauper burials can be conducted at the College ground, so my guess is that the parish didn't yet need Cross Bones for that purpose. (109)

"It became the parish poor ground in due course, though the exact date for the first parish interment in the cemetery is uncertain," the MoL report says. "[The St Saviour's price list] makes no mention of either the Cross Bones or the New Churchyard. This suggests that it was not in use as a parish burial ground at that time, though this does not rule out its usage as the earlier 'Single Women's burial ground'."

We know from the St Saviour's parish register covering 1538-1563 that the churchwardens there were already marking out the prostitutes presented for burial, which suggests they were somehow segregating those particular graves long before 1594. As Carlin points out, this register "carefully notes the burials of prostitutes as, eg, 'Alys, a singlewoman' or 'Margaret Savage, common woman', while taking only rare note of the occupation of others buried". Perhaps it suited St Saviour's to let these women be interred at a quasi-official graveyard in the Bishop of Winchester's Clink Liberty? The Liberty governed every aspect of these women's lives in the early 16th century, after all, so why not let the Bishop's men bury them too and keep the parish's own grounds untainted?

Whatever the history of Cross Bones before St Saviour's Parish got involved, it was surely the increasing pressure on all Southwark's burial grounds which led to the site being officially adopted. Plague took a heavy toll on the Borough throughout the 1600s and it was St Saviour's paupers who bore the brunt. In the plague year of 1625 alone, the parish had to find somewhere to bury 2,346 bodies, which Rendle estimates to be fully one third of St Saviour's population. This load was further increased by the 17th century's three exceptionally severe winters in London - those of 1608, 1615 and 1622 - which killed close to 300 people a week in the city and hit the poor hardest of all.

Taken together, these figures demonstrate both why Cross Bones has always been crammed so tightly with dead and why no skeletons from Stow's time remain there today. "A widespread response to the growing shortage of space, especially in the inner city, seems to have been to pack the maximum number of corpses into the available ground," Houlbrooke writes. "In so far as charnels were employed, it was in a more casual fashion than in medieval times. Where they did survive, their contents were probably treated with scant respect. 'Our bones in consecrated ground never lay quiet,' John Aubrey wrote. 'And in London, once every ten years the earth is carried to the dung wharf'." (110)

It was also the 1625 plague outbreak which prompted one Southwark gravedigger to complain he was out of pocket by £11 and 15 shillings because of the huge number of poor people he'd been forced to bury without pay during those years. The 1613 St Saviour's price list I mentioned earlier shows that just the patch of earth for your loved one's burial could cost anywhere from twopence (with no coffin) in the parish's College ground to two shillings (for a coffin burial) in St Saviour's Churchyard itself. On top of that must be added up to 16 pence for the Minister's services, another 16 pence for the gravedigger and fourpence each for bearers. Even if you picked the cheapest possible option in every category, it would be hard to bury your loved one for less than three shillings and sixpence and that was a sum far beyond what many in St Saviour's could pay.

"Burial fees often represent many days' wages for a labouring man or woman," Boulton told me. "And that bill would come just as family finances might be tighter than normal following medical costs, loss of wages and possibly the loss of a main breadwinner." That's why so many families around Redcross Way had no choice but to opt for a pauper funeral instead and accept whatever godforsaken graveyard the parish might consign them to. (111, 112)

Charles I came to the throne in 1625 and immediately ordered a clean-up of the red light districts closest to London's walls. He left Southwark alone on that occasion, but attendances at its brothels, theatres and bear gardens were already declining. Although germ theory was still a couple of centuries away, people may already have intuited that the crowded, filthy streets of this very poor area offered more risk of infection than most. The prevailing theory at this time was that disease spread through foul air, so the stench of Southwark alone must have been enough to make many people fear visiting it. As with every outbreak of plague that century, anyone rich enough to flee London for the countryside did so with all possible speed. (113)

The plague returned more virulent than ever in 1630 and this time the authorities reacted by ordering Bankside's theatres, bear pits and other amusements to close down until the disease had retreated again. The idea seems to have been to discourage people from gathering in large crowds or - if they must do so - to choose a less disease-ridden borough than Southwark for their revels. The authorities had always viewed actors and playwrights as a potentially seditious lot, so silencing their voice may have also appealed for that reason.

Indirectly, these closures hit the brothels too. "If the pattern of previous outbreaks was followed, it could be expected that the normal 'let us be merry for tomorrow we die,' attitude would enable the prostitutes to carry on," Burford writes. "But on this occasion, the deaths from plague were very numerous and doubtless everybody who could get away did so. The Bankside never fully recovered from this blow." Another closure of the theatres followed in 1640 and then - the big one - in 1665. Before we get to that terrible year, though, there's the little matter of the English Civil War to deal with.

Indirectly, these closures hit the brothels too. "If the pattern of previous outbreaks was followed, it could be expected that the normal 'let us be merry for tomorrow we die,' attitude would enable the prostitutes to carry on," Burford writes. "But on this occasion, the deaths from plague were very numerous and doubtless everybody who could get away did so. The Bankside never fully recovered from this blow." Another closure of the theatres followed in 1640 and then - the big one - in 1665. Before we get to that terrible year, though, there's the little matter of the English Civil War to deal with.

This war had been brewing ever since 1629, when Charles I dissolved the English Parliament for defying his financial and religious policies, then began an 11-year period of direct personal rule. He was forced to reconvene Parliament in April 1640 because he needed it to grant him money for his battles against the Scots, but once again MPs refused him and Charles dissolved their assembly after just one month. When he tried again that November, a zealous group of Protestant/Puritan MPs - many of whom suspected Charles was a secret Catholic - used the Parliament's gathering to voice angry complaints against him.

Relations between the King and his Parliament sank still further in January 1642, when Charles marched his men into the House of Commons and attempted to arrest five of its most troublesome MPs. They slipped away safely and Charles declared open hostilities in August that year by raising his standard at Nottingham Castle and inviting loyal subjects to rally behind him. The opposing Parliamentary army was led by Oliver Cromwell and the resulting conflict kept England at war with itself for the next nine years.

The same group of Puritan zealots who'd defied Charles in 1640 were keen to purge sinful pleasures from the land. They didn't limit themselves just to Southwark in this ambition, but naturally enough it was a major target. "In April 1644, Parliament closed all whorehouses, gambling houses and theatres," Burford writes. "The players were whipped at the cart-arse, fined for using oaths or sent to prison. Maypoles were pulled down wherever they could be found on the grounds that they incited the peasantry to lust. Nude statues, when not broken up, had their genitals covered with leaves and scrolls."

Southwark's taverns were left largely unmolested in this clean-up, if only because they were woven so tightly into people's everyday lives. Unlike every other policing body that had declared its intentions to clean up Bankside, the Puritans were fanatical enough to refuse the innkeepers' bribes, so any sexual trade that continued there had to move deeply into the shadows.

The Puritan forces in Southwark were supported by the hundreds of Dutch and Flemish Protestants who'd emigrated there since 1575. Despite their countrywomen's reputation for supplying Bankside's most expert prostitutes, most of the new arrivals were sober artisans, who'd begun to industrialise large parts of the Borough. They'd became more fiercely protestant than ever when Charles I took the throne - blame those suspicions about his Catholic sympathies again - and helped to ensure that Southwark sided firmly with the Parliamentarian side when civil war began. And perhaps we shouldn't be surprised by this: no-one saw the violence and disease Bankside's seamy trade created more clearly than those who had to live on its doorstep.

Cromwell's army won a major victory at Preston in August 1648, charging the King with high treason and having him publicly executed in Whitehall five months later. His son, Charles II, who'd fled to Scotland, continued to fight Cromwell till September 1651, but his defeat that month at Worcester proved the war's last major battle. Two years later, in December 1653, Cromwell declared himself England's Lord Protector - a post that amounted to the monarchy in all but name.

Re-ordering Southwark under his new regime, Cromwell sold the old Clink Liberty's lands to a property developer called Thomas Walker. Walker added another chunk of real estate he'd bought from Southwark Manor and set about tearing down every building he found there to build tenements instead. This constant redivision of Southwark's housing into smaller and smaller units left the Borough a warren of packed tenements and dark, narrow alleyways strewn with both human and animal dung. Chamber pots were still the only form of indoor lavatory at this time and these were emptied from the tenement windows directly into the alley beneath. The rats which carried plague-bearing fleas to Bankside could hardly have asked for a better home.

When Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, his son Richard plunged the country into chaos by assuming he could simply inherit the Lord Protector's role as if it really were the hereditary Kingship. It was only after Richard had been overthrown and Charles II invited to return to England as monarch in 1660 that some semblance of order was restored. Five years later, we were back to the plague again.

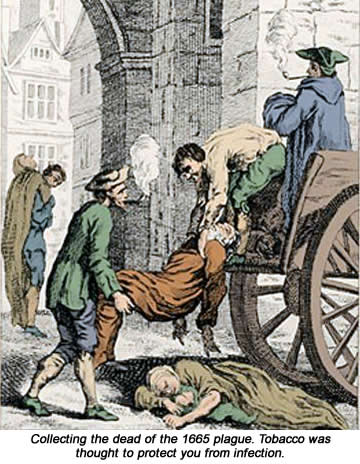

It's the 1665 outbreak which we today call The Great Plague and there's no doubt that it deserves that name. Even the official Bills of Mortality admit that a total of 68,596 Londoners were killed by this outbreak during its 15-month run. That alone would make its toll over 10% of the city's population, but it's generally agreed today that these official figures seriously underestimate the true number of deaths. The more likely total in London over that period is 100,000 (or 15%) and, as always, it was in slum areas like Southwark that the infection spread fastest of all. (114)

In the midst of this outbreak, journalist Henry Muddiman wrote a letter from London to the Government minister Joseph Williamson. Muddiman reports that the city's burials in that week alone had reached 8,252, of which 6,978 were plague deaths. Samuel Pepys gives us similar figures in his diary entry for August 31, 1665. "This month ends with great sadness upon the public through the greatness of the plague," he writes. "In the City died this week 7,496; 6,102 of the plague". Both Muddiman and Pepys here were writing at something like the peak of plague deaths, but the fact that they're quoting the official Bill of Mortality's statistics means even these horrendous figures are likely to be an underestimate. Pepys acknowledges as much in the same day's entry, adding: "It is feared that the true number of the dead this week is near 10,000." (115, 116)

With so many bodies to be collected and disposed of, the parish authorities struggled to keep up, eventually resorting to stacking decomposing corpses in the street until their over-loaded carts could dump their cargo in the nearest plague pit and return for more. Collections and plague burials were first conducted at night to avoid public alarm, but this restriction soon proved impractical. "The people die so, that now it seems they are fain to carry the dead to be buried by day-light, the nights not sufficing to do it in," Pepys' August 12 entry tells us. Three weeks later, on September 6, he remarks how strange it is to see burials conducted in broad daylight on Bankside, "one at the very heels of another: doubtless all of the plague".

One plague pit in Aldgate housed over 1,100 corpses, which arrived with such relentless speed that they were being dumped in at one end while workmen still dug at the other. Daniel DeFoe, in his Journal of the Plague Year, tells us that in London "many if not all of the out-parishes were obliged to make new burying-grounds" and there's no reason to think St Saviour's would have been an exception. Lord Brabazon, writing to The Times in 1883, claims to have seen 17th century records showing that many victims of the 1665/66 plague were buried at Cross Bones itself, where "in one week upward of 600 bodies were interred".

The combined effect of the puritans' crackdown on Bankside, the repeated closure of theatres and bear-pits there and the unprecedented number of plague deaths in this latest outbreak was to end its status as London's Trastavere once and for all. A few entertainments, such as bear-baiting and prize fights, resumed there after the Great Plague, but Southwark would never again have the critical mass of theatres, whorehouses, taverns and gambling joints which fed one another's trade and made Bankside so much more than the sum of its parts. By 1682, even the last bear-pit had closed.

What we might call the professional whores had already moved north of the river back in Cromwell's day, as had the most organised brothels themselves. The fact that so many poor women lived in Southwark ensured that casual street prostitution continued there as it always had - the women in question simply having no other means to feed themselves - but that was true of every other slum neighbourhood in London too. (117)