Chapter 1: The Romans

1) The Bishop's Brothels, by EJ Burford (Robert Hale Ltd, 1976). I've drawn very heavily on Burford's book for the first half of this narrative. For anyone with an interest in the seamier side of London history - Southwark's history in particular - it's an essential and hugely entertaining read.

2) Even bakers and cookshops had slaves for this purpose - known as the elicariae - who were sent out to the roadside selling cakes shaped like male and female genitalia. The understanding was that anyone selling these cakes would double as a prostitute when necessary. Competing with them were the independent whores Romans called noctilae ("night moths") and those prepared to accept even the lowest copper coin made for their services - the quadrantariae.

3) The stola, a long pleated dress, was seen as the mark of a respectable woman in Rome and for a prostitute to wear one would have been considered serious misrepresentation. This idea returned to Southwark with the 12th century ban on whores wearing aprons.

4) Underground London, by Stephen Smith (Abacus, 2004)

5) Here's Burford describing the goings-on at one of Harpocrates' celebrations: "Crowds of crazed women would dance and cavort, exposing themselves stark naked and copulating publicly with all comers. Females would hang garlands on the god's enormous penis, as many as they had had lovers the previous night. Often, the penis would be completely ringed and covered from sight with the offerings of a single woman."

Chapter 2: Arriving at the vigil

6) The lights are a Southwark Council art project, unveiled in August 2008.

7) My notes from that night read: "Guardian-reading, cat-loving, vaguely mystical types, often quite mumsy. Kind-hearted and well-meaning. Not as nutty as you might imagine - no fancy dress. Handful of men only. One well-groomed hippy type with long hair and beard. A Japanese girl. Some quite young women: 20s rather than 30s".

8) Personal interview at Nelson's café, Southwark, November 2012.

9) I Was An Alien Sex God is full of LSD references, so I couldn't resist asking Constable if his meeting with The Goose had been pharmaceutically assisted in any way. He told me he'd taken nothing at all on that particular night.

10) The Southwark Mysteries, by John Constable (Oberon Books, 1999).

11) Cross Bones is, quite literally, just around the corner from an excellent little London theatre called The Menier Chocolate Factory. Whenever I went to a play there, I'd nip out to Redcross Way during the interval to see if anything interesting had been added to the gates since my last visit. The Menier's won a huge reputation for its staging of Stephen Sondheim musicals and Sondheim himself has visited the theatre several times. I often wonder if anyone there has ever taken this opportunity to show him Cross Bones.

12) All the Guadalupe and Santa Muerte decorations were carefully removed and taken home after the night's celebrations, as they would certainly have been stolen otherwise. One of my favourite examples of the gentle humour often expressed at Cross Bones was the crocheted ornament attached to its gates in 2011, mounted on a cardboard surround warning: "Crochet thieves operate in this area".

Chapter 3: Laying siege

13) If you're wondering how to pronounce "Southwark", just add a "k" to the end of "mother" and make it rhyme with that. It's "Suhth-erk", with a slight emphasis on the first syllable.

14) About half of William's army was made up of foreign mercenaries, most of them Flemish, and this may explain how Flemish women later gained such a strong hold over Southwark's brothels.

15) From the BBC website's Christianity in Britain.

16) Personal interview at Southwark's John Harvard Library, November 2012. This library's named after the founder of Harvard University, whose family once owned a Borough High Street coaching inn called The Queen's Head. John left Southwark for Boston in 1637 after the rest of his family was wiped out by plague.

17) The Church made this problem even worse in 1129 when it ruled that all priests must in future be celibate. Priests who were already married were told to evict their wives from the family home, putting yet another wave of destitute women on the streets.

Chapter 4: Samhain at the gates

18) Honouring The Outcast Dead: The Cross Bones Graveyard, by Dr Adrian Harris

19) There weren't enough leaves in the bundle for everyone in the crowd to get one. Having shuffled forward so determinedly to make sure I got a leaf, though, I was damned if I was going to give it up. This suggests that my own spirituality still has some way to go.

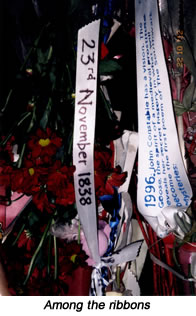

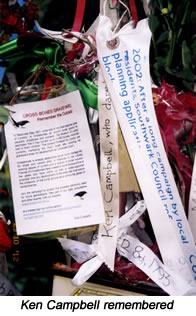

20) Quote taken from JandBFrench's short YouTube film Where The Prostitutes Were Buried in London.

21) Some people never did find the right moment to read out their own ribbon, either because they were slightly embarrassed at the procedure or because they were reluctant to pipe up when others were talking. I think some people decided to take their ribbons home as souvenirs rather than attach them to the gates - something I was sorely tempted to do myself.

22) It was only after the ceremony ended that I noticed I'd been so intent on making sure the knot in Eliza's ribbon held firmly, that I'd managed to tie it right in the middle of her name. Fortunately, the age and date draped down nicely on either side of the knot, so I smoothed those into place instead.

23) The knots required often make it hard to read the full details on any Cross Bones ribbon, either in photographs or on the gates themselves. I have managed to transcribe a few though: "February 14th, 1785. Jane Jollif, a widow, aged 41 years"; "July 1840. Elizabeth Lade, Hart Inn, Age 1 year 6 months"; "Winter 1837, William Pearce"; "23rd October, 1833. Jane Stevens, Union Street, two years old"; "October 31st, 1728. Sarah Whitehead" and; "December 25th, 1726. Mary, wife of George Wilson, a carpenter".

24) Letter to The Times, November 10, 1883.

25) One Friends of Cross Bones supporter has proposed a monument to Britain's prostitutes as part of any memorial garden that's eventually built there. His design shows Christine Keeler in this famous pose.

26) A Book of Hours was a medieval volume collecting the particular prayers to be recited at each of the day's seven canonical hours: Matins, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers and Compline. The idea was that lay Christians could use these books to copy the daily routine of a monastery.

27) Cheap gin was one of the very few comforts available to the women destined for a Cross Bones burial and that's why it's become so central to the site's rituals. Gin's popularity among women later gave it the nickname "mother's ruin".

Chapter 5: Birth of the Liberty

28) This principle gives us benefit of clergy and Psalm 51's role as the "neck verse". At a time when literacy was rare, simply showing you could read was taken as ample proof you were a member of the clergy. By reading Psalm 51 aloud in court ("Oh God, have mercy upon me."), a defendant could establish the secular courts had no right to try him and so escape a possible sentence of hanging. The principle was later extended to anyone who could read - clergy or not - and saved Ben Jonson's life when he was charged with manslaughter in 1598. Benefit of clergy's scope was steadily eroded over the following 200 years, but it wasn't finally abolished in Britain until 1823.

29) "These estates were later to become known as 'the Liberty of the Bishop of Winchester', Burford continues. "Indeed, they may have been so designated even at this early date, but contemporary records are lost."

30) In the 225 years from 1330 to 1555, England had six Lord Chancellors who were also Bishop of Winchester, accounting for 29 years of the Chancellorship between them. Outside the royal family itself, only the Lord High Steward of England had more power than the Lord Chancellor.

31) When Burford's book was published in 1976, many scientists thought syphilis may have been present (though unidentified) in Europe as early as the sixth century. But a 2011 study produced convincing evidence that the disease was brought to Europe by sailors returning from the Americas after Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage. Atlanta's Emory University analysed 54 published reports identifying syphilis in skeletons from before 1492, but concluded that either the diagnosis or the bones' own dating was mistaken in every case.

32) Bishops had other ways of profiting from sexual desire in this era too. Priests at the time were technically celibate, but could pay the Bishop ruling their diocese a fee called a couillage which licensed them to keep a servant called a hearth girl living in their house. These girls, as Burford puts it, "kindled other fires as well". Rabelais, with his characteristic frankness, called the couillage fees "bollock money".

33) Dr Johnson did much of the work on his 1755 dictionary while staying at The Anchor on Bankside, so he knew the area well. Defining a stew as "a brothel or house of prostitution", he adds: "The signification is by some imputed to this, that there were licensed brothels near the stews or fishponds in Southwark; but probably stew, like bagnio, took a bad signification from bad use." One of the sources Johnson cites for this is Act 5, Scene 1 of Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, where the punning Duke Vincentio says: "I have seen corruption boil and bubble / 'Til it o'er run the stew".

34) "Centuries later, Charles II was enraged to discover that his parliamentary supporters were in the brothels when they should have been [voting]," Burford says. "One of the King's vital measures was lost as a result."

35) The Medieval Castle in England & Wales: A Political & Social History, by Norman Pounds (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

36) The Bishop's court officials may also have been keen to crack down on low-level corruption among constables and bailiffs to prevent bribes being skimmed off at that stage. Only if a case came to trial could the court's officials hope to be bribed instead.

37) London's had many colourful street names which owe their origins to medieval prostitution. The most notorious example is Gropecunt Lane, an alleyway off Cheapside first recorded under that name in 1279. It was flanked by Burdell Lane (an early version of Bordello Lane) and Puppekirty Lane (Poke-skirt Lane), but all three have since been obliterated by development. Oxford's Magpie Lane and Norwich's Opie Street were both once known as Gropecunt Lane too and for precisely the same reason. The name didn't finally fall out of use in Britain until 1561.

38) Fifteenth century Paris had Rue Grattecon, Rue Poilecon and Rue de la Con Reerie. Readers are cordially invited to translate these names for themselves.

39) Encyclopedia of Prostitution & Sex Work Volume 1, by Melissa Hope Ditmore (Greenwood Publishing, 2006).

Chapter 6: Emily's plaque

40) South London Press, November 6, 1998.

41) One of the most powerful moments I experienced at the theatre in 2011 came while watching Alecky Blythe's London Road at the National. Blythe tells the story of the Ipswich murders mostly from the point of view of people living in the town's red light district, but reserves one scene for the victims alone. Five actresses representing Gemma, Anneli, Paula, Netty and Tania stood stock-still on a silent stage, glaring out at the audience for what felt like a very long time. "Don't you dare forget us," they seemed to be saying. "Don't you fucking dare!"

42) Financial Times, December 27, 2008.

43) The Hop Cellars is still a pub, but now it's called The Wheatsheaf.

44) The Independent, October 31, 2009.

Chapter 7: The Black Death

45) Rosa Anglica, by John of Gaddesden (1280-1361). Quoted in Burford, above. John hints his treatment will prevent unwanted pregnancy too.

46) John Wycliffe, the 14th Century religious dissident, warned that monks and friars at this time were claiming medical knowledge in order to seduce local women. They targeted women whose men were away from home for some reason and told them no woman could remain healthy without regular sex. In Of the Leaven of Pharisees Wycliffe writes: "When Lords [husbands] are away from home in wars or in justice or in parliament or in other lordships and when merchants do be in the country and when plowmen do be all day long in the fields, then these pharisees [lecherous ones] run fast to their wives under cover of holiness and fornicate with them."

47) Other whore-packed Southwark streets, such as Maiden Lane and Love Lane, were named more ironically. The sarcastic wit applied in christening these streets often ensures their names survive where cruder ones did not. You'll still find Maiden Lane on the Southwark map today.

48) Henry Harben's 1915 Dictionary of London tracks one alleyway's name changing from Shitteborwelane (1272) via Shitbourn Lane (1394) and Shetenborn Lane (1539) to the innocuous Sherborne Lane today. "Burn" is an old Scots word for stream and this alleyway seems once to have been a popular public convenience: Shitstream Lane.

49) Rick Powell from the UK's Federation of Burial & Cremation Authorities told me a buried adult body takes about 12 years to reduce itself to bones and a child's just six. In times of plague, bodies were often disinterred much sooner.

50) Death, Religion and the Family in England 1480-1750, by Ralph Houlbrooke (Clarendon Press, 1998).

51) My understanding is that cases of murder in the Liberty went to the King's courts rather than the Bishop's. Perhaps the Bishop's court simply recorded these two cases before passing them to the King for trial?

52) This episode came as part of the Peasants' Revolt. Tyler's men were rebelling against a poll tax imposed by Richard II and demanding an end to the social structure that kept them in serfdom. Tyler was killed two days after the Southwark massacre when he confronted both the King and Walworth at Smithfield and some accounts say Walworth himself dealt the fatal blow. The revolt petered out at that point and Tyler's head was later displayed on London Bridge as a warning to anyone else who felt like making trouble.

53) The Westminster Chronicle 1381-1394, ed. LC Hector (Clarendon Press, 1982)

54) Medieval Southwark, by Martha Carlin (Hambledon Press, 1996). Stewholders were expected to be married men, whose houses were to be used as brothels only.

55) Among the single women who supported themselves without prostitution in Southwark, the most common trades were preparing food or peddling it through the streets (26%), textiles work such as spinning yarn (25%) or working as a seamstress (21%). "This suggests that most of the female householders of Southwark had slender economic resources, insufficient to keep a shop, a stock of goods or expensive tools," Carlin writes.

56) This was the raucous England of Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote The Canterbury Tales in the 1390s, using a real Southwark tavern called The Tabard as the book's first setting. In her own tale, the Wife of Bath reminds her grumpy husband that she could easily earn a living without him just by selling what's between her legs: "If I would sell my pretty thing / I could walk as new-clothed as a rose / But I will keep it for your own pleasure".

57) I don't know how long Brenchesle and Osteler were kept in the Tower of London, or indeed if they ever emerged. Richard II, the man who'd sent them there, ended up in the Tower himself in 1399, where he was imprisoned before being taken to his death in Pontefract Castle.

58) By "canal dung" the report means filth from the sewer ditches.

59) In March 1543, a gang of hooligans including the Earl of Surrey was brought to court for taking a row boat out on the Thames and using catapults to fire stones at the whores hanging out of the Bankside windows. Their punishment is not recorded.

Chapter 8: The Invisible Gardener

60) Calling our cafe meeting an interview makes my role sound far more important than it was. John's so passionate about Cross Bones that all I really had to do there was ask a single opening question, then sit back and let him talk. He scarcely paused for breath until about 40 minutes in and then only because he'd made a particularly expansive gesture which sent coffee flying everywhere!

61) For my full account of William Kirwan's murder see The Borough Mystery elsewhere on PlanetSlade.

62) The most interesting piece of recent graffiti on the door that day read: "RIP to the sket you used to beat! Her days are over. Devonport RIP". Sket is a slang term roughly equivalent to "slag" or "ho" and still current usage among British youth as recently as 2011. Whether you take the tone of this message as gleeful or mournful, it suggests that a whole new generation has discovered Cross Bones and understands its role.

63) London SE1 Community Website. Porter's unfortunate tone in this post makes him sound like a rather prim poverty tourist. To give him credit, though, he does seem to have drawn the state of Cross Bones to the police and council's attention and perhaps this helped to prompt the clean-up that followed.

64) Transport for London owns the Cross Bones site, but leases it out to Network Rail for work on the Thameslink project. Network Rail uses the northern half of the site to store its vehicles, but has so far left the southern half - where the graves themselves are located - alone.

65) The Independent, March 15, 2009. The 40-storey Swiss Re building, better known as The Gherkin, is clearly visible from Cross Bones.

66) Sunday Times, September 20, 2009.

67) This piece appears on The Cross Bones Chronicles website, but the writer's not credited by name. The Museum of London (MoL) excavation mentioned is their 1993 dig at Cross Bones, which we'll come to later.

68) When I last visited Cross Bones in August 2013, a chunky new bike chain had appeared locking the site door tight shut against its jamb. What this will mean for future access and maintenance remains to be seen.

Chapter 9: Farewell to the stews

69) Syphilis takes its name from a 1530 poem by Girolamo Fracastoro. He invented a mythical shepherd called Syphilus who insults the Sun God and is struck down with a hideous disease whose symptoms matched the new infection sweeping Europe. When he chose the name Syphilus, Fracastoro may have wanted his readers to think of Sisyphus and that character's own unending pain.

70) Among the common people, syphilis was known either as "the great pox" (to distinguish it from smallpox), or named for whichever country the speaker's native land happened to dislike most. The English and the Italians called it The French Disease, the French called it The Spanish Disease, the Russians called it The Polish Disease, the Polish and the Persians called it The Turkish Disease, the Indians called it The Portuguese Disease and the Tahitians called it The British Disease. In Germany it was known as The French Evil, in Japan it was The Chinese Pox and in Muslim Turkey people called it The Christian Disease.

71) The Guardian, May 17, 2013.

72) The first use of condoms for disease control seems to have come around 1550, when the Italian anatomist Gabriele Fallopio tested a sheath made of sheep's intestines, which tied at the base of the penis with a ribbon. He concluded that it prevented transmission of syphilis, but it would be another century before the idea caught on in Britain. Until the early 1900s, when the first disposable condoms were introduced, the gentleman gave his sheath a quick rinse out after every encounter, then tucked it back in his wallet for further use.

73) Venice had a reputation for running Europe's most hygienic and best-organised brothels, where the girls were said to be both elegant and well-mannered. If syphilis couldn't be controlled even there, what chance did less punctilious cities have?

74) Winchester was then the wealthiest Bishopric in England, so there's no doubt Foxe was a very powerful man. Even today, the Lord Privy Seal is automatically given a place in the Cabinet of any British Government.

75) To understand what a vast sum £5 was at this time, consider the funeral accounts of Anne Fortesque, an Oxfordshire noblewoman who died in 1518. Her elaborate funeral cost a total of only £39. The catering budget accounted for just over £10 of this, but still provided plenty of food and drink for all the 300 mourners attending.

Chapter 10: The Southwark Mysteries

76) Sunday Telegraph, May 14, 2000.

77) Southwark Mysteries website.

Chapter 11: Bardic Bankside

78) A Notable Discovery of Cozenage, by Robert Greene (1591). An added refinement to crossbiting today is that the pimp starts taking cellphone photographs the moment he walks in and threatens to distribute them on the internet.

79) A jaxe of course (more usually spelt "jacks" or "jakes") is a lavatory, so the clergyman here was echoing Thomas Aquinas' 13th century remark about the palace cesspool.

80) London: The Biography, by Peter Ackroyd (Vintage, 2001). Ackroyd's view - and I think it's right - is that this attitude towards Southwark didn't change till the Jubilee Line extension became necessary in the late 1980s.

81) Published in Holinshed's Chronicles, 1577.

82) "From the late 16th century onwards, a growing number of parish overseers' accounts record disbursements for poor people's burials, especially the shroud and the grave," Houlbrooke writes. Coffins were seldom used for ordinary burials until about 1650. Until then, poorer people would simply be buried in a shroud or winding-sheet.

83) Thomas Platten, a Swiss traveller describing his visit to London in 1599, writes that he found whores swarming around every tavern and playhouse in the city, as well as several child brothels in which girls aged from seven to 14 were supplied. He doesn't say where in London these brothels were, but every other taste was catered for on Bankside so I've no doubt this one was too.

84) I've only been to Tijuana once and even then it was just a day-trip from San Diego. The coach driver told us he'd taken another tourist group down there a few months earlier, but that one guy had failed to appear back at the bus for the return journey. They waited as long as they could, but eventually had to go back across the border without him. Two weeks later, this same driver was waiting at the Tijuana pick-up point again when the missing tourist staggered up. He'd lost his wallet and one of his shoes, his clothes were all over the place and he hadn't slept in days. Quite how the details were worked out at US immigration, I don't know, but they managed to get him back home in the end - where he faced a rather awkward interview with his wife.

85) There's a 1992 episode of The Simpsons where Krusty the Clown refers to Tijuana as "the happiest place on Earth". Krusty would have loved Shakespeare's Bankside.

86) Shakespeare's Restless World: Swordplay & Swagger (Radio 4, April 2012). Still available on the BBC iPlayer here.

87) After this tour-de-force explanation from Dark, I offered my own summing-up: "So it's Boardwalk Empire meets Deadwood with a touch of Breaking Bad?" She laughed. "Yes, exactly - plus bears!"

88) I've told this story a little more fully elsewhere in the piece. Depending which version you're reading, you'll find it as either box copy or an appendix.

89) Leslie Hotson's 1931 book Shakespeare vs. Swallow describes William Gardiner's life as one of "greed, usury, fraud, cruelty and perjury". I think it's safe to assume from this that he was related to the gangster clan of Gardiners involved in running so many Bankside brothels.

90) Shakespeare originally named his Falstaff character Sir John Oldcastle, perhaps with the idea of teasing the real Oldcastle's descendent Lord Cobham. Oldcastle was actually a protestant martyr of very sober habits, so Lord Cobham was not amused. He insisted that Shakespeare change the character's name, backed that demand up with various threats and duly got his way. The playwright was sufficiently shaken by this to add a disclaimer about Falstaff in his epilogue for Henry IV pt 2. "Oldcastle died a martyr and this is not the man," he has the play's final speaker say.

91) The remark about honour, of course, is Falstaff's own. It appears in Henry IV, pt 1.

92) The Annals of London, compiled by John Richardson (Cassell & Co, 2000).

93) Henry VI, pt 1: Act 1, scene 3.

94) Troilus & Cressida: Act 5, scene 10. Cassell's Dictionary of Slang cites a similar usage in 17th century popular speech: "No goose bit so sore as Bess Broughton's". Broughton was London's most famous whore at that time.

Chapter 12: Going underground

95) Altered State: The Story of Ecstasy Culture & Acid House, by Matthew Collin (Serpent's Tail, 1997).

96) The Cross Bones Burial Ground, Redcross Way, Southwark, London: Archaeological Excavations (1991-1998), by Megan Brickley, Adrian Miles and Hilary Stainer (Museum of London, 1999).

97) There had been warehouses occupying the footprint's ground until the 1980s and the MoL found foundations for these buildings as they dug. The builders who'd put those warehouse up had stacked the bones they disturbed neatly into the construction trenches lining the foundations' walls.

98) History Cold Case: Crossbones Girl (BBC 2, first aired May 2010).

99) The idea of Christ rising in the east seems to be a mixture of sunrise symbolism and the fact that Jerusalem lies to the east of Britain. For corpses in the third or fourth layer down at Cross Bones, their first experience of resurrection would presumably be banging their head on the coffin above.

100) I'm using our modern understanding of the word "children" here as referring to anyone under 18 years of age. Infant burials in St Saviour's Parish spiked every summer, as the hot weather made children more susceptible to dysentery. The detailed figures appear in the MoL's full report here.

101) Ken Campbell was, in the words of Ian Shuttleworth, "one of Britain's premier theatrical fruitcakes". In addition to staging The Warp's first production and a Pidgin English Macbeth, he toured his own one-man shows on the history of ventriloquism and all kinds of Forteana. When Campbell died in 2008, Constable ensured he got a ribbon of his own on Cross Bones' gates. For more on The Warp, see Ian Shuttleworth's site here.

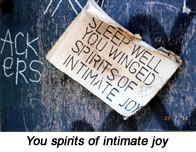

102) I was once lucky enough to spend a day with Campbell, but that story would require a whole essay of its own. My favourite anecdote about him concerns the Pidgin Macbeth he staged at London's Piccadilly Theatre in 1999. Lady Macbeth's, "Come you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts, unsex me here" became, "Satan, takem me handbag".

Chapter 13: Puritans & plagues

103) Old Southwark & Its People, by William Rendle (W Drewett, 1878).

104) The terms "Redcross Way", "Redcross Alley" and "Redcross Court" were used interchangeably by the people living there in the 1800s. It's clear from context that they have the same street in mind whichever name they give it.

105) John Stow's Survey of London (1598).

106) By "excluded from Christian burial" here, I think Stow must mean they were buried in unconsecrated ground. Since the Reformation of the 1530s, that issue was irrelevant in the church's official doctrine, but it may still have mattered to the common folk. See the relevant box copy/appendix for further discussion of this point.

107) Houlbrooke thinks only an official condemnation by the Church would be enough to bar a woman from parish burial. "I think that only a known formal sentence of excommunication (in theory quite possible for a notorious prostitute) would have been sufficient to deny her churchyard burial," he told me. Other stewhouse girls may have finished up at Cross Bones simply because they required a pauper burial.

108) Histories and Antiquities of the Parish of St Saviour's Southwark, by Matthew Concanen & Aaron Morgan (1795). Concanen was a poet, essayist and political pamphleteer who also spent 16 years as Jamaica's attorney general. His mischievous 1728 piece An Essay Against Too Much Reading was the first published article to claim Shakespeare hadn't written his own plays.

109) The MoL has found evidence of seven burial grounds in St Saviour's Parish altogether, only three of which were used by the parish authorities. The three parish grounds were St Saviour's own churchyard, the College Churchyard in Park Street (used by St Saviour's Almshouse) and Cross Bones (the parish poor ground). The other four sites were Deadman's Place (used first as a plague pit then by the adjacent Independent Chapel), the Baptist burial ground in Bandy Leg Walk (now part of Southwark Bridge Road) and two Quaker grounds (one on Ewer Street, the other on O'Meara Street).

110) John Aubrey (1626-1697) is best known as the author of Brief Lives. The dung wharf he mentions loaded cemetery bones on to waiting barges. These bones would later be ground into a phosphorous-rich power for use as agricultural fertiliser.

111) Boulton also quotes the accounts from Richard Bird, a Southwark vintner, whose family spent 15 shillings and twopence to bury him in 1626. This broke down to ten shillings and twopence for the ground, the funeral cloth and tolling of the church bell, three shillings paid to the minister, clerk and sexton (between them), fourpence each to the bearers and eightpence for the gravedigger. This would have been a relatively grand funeral by Southwark's standards at the time and far beyond what most people living there could expect.

112) Once coffins became obligatory for even pauper burials in around 1650, some parishes experimented with a re-usable model. This had a hinged underside which allowed the body to be dropped discretely into the grave without burying the coffin too. This was thought to be a step too far, however and the practice was quickly abandoned.

113) The Clink Liberty's special status was briefly renewed under both Charles I and Charles II. I get the impression this was done purely as a courtesy to the Bishop of Winchester, however and that real power over the Liberty's affairs remained outside his hands.

114) I checked with Patricia Dark to see exactly what geographical area these Bills of Mortality covered. "The city of London, the city of Westminster and the borough of Southwark were included in the Bills of Mortality, along with the parishes of Lambeth, Rotherhithe, Newington and Bermondsey," she told me. That means that the whole area covered by the modern boroughs of both Southwark and Bermondsey would have been counted in the Bills' 1665 plague deaths.

115) Muddiman also tells the story of a Newgate butcher declared dead of plague by the parish corpse collectors, but left laid out in his room overnight because their cart was already full. Next morning, the butcher's daughter went into that room and was startled to hear her father beckon her over to ask for a glass of ale. "The man took a pipe of tobacco, ate a rabbit and on Sunday went to church to give God thanks for his preservation," Muddiman writes. Many families preferred to keep their deceased laid out at home for a few days to guard against just this possibility, a practice which added still further to infection rates.

116) In the case of private burials, even quite wealthy families might delay interment by as much as two weeks. Houlbrooke quotes the instructions given to Dorothy Wood's coffin-maker in 1704: "Be pleased to take care of the inside, for the Gentlewoman is not design'd to be buried this fortnight". The writer is asking for the coffin's interior joints to be pitch-sealed with particular care to minimise any escaping smell.

117) Some of the Bankside girls opted for a trip to America, where they were sorely needed by the male settlers who'd followed the Mayflower's 1620 voyage there. "The great majority were enabled to start new lives, get married and become the mothers of many respected daughters of the American Revolution," Burford writes.

Chapter 14: Crossbones Girl

118) The MoL's archaeologists found this particular skeleton in a cheap, ramshackle coffin less than three feet below the surface. Other coffins were packed just an inch or two away on all sides, with eight or nine more layers stacked beneath.

119) Green's original report for the BBC contains a lot of information that never made it into the finished programme. That's where most of his quotes come from here.

120) The camera caught Black as she studied the skull's accumulation of distorted syphilitic bone. "That's just horrendous," she murmured. "That must have been so painful."

121) This is a belief still held in some parts of Africa, where it's held to be a cure for Aids. "You have huge HIV numbers and nobody is educated on how you get HIV," the actress and campaigner Charlize Theron said of her native South Africa in 2009. "Many think if they rape a child or virgin they will be cured of the disease." The 2011 Broadway musical The Book of Mormon mocks this superstition with an African character called Middala, who has to be talked out of finding a baby to pursue his own treatment.

122) The best you could hope for from mercury treatment was that it would slow the progress of your syphilis. It certainly didn't offer a cure and its side effects were hideous: vomiting, hair loss, amnesia, depression and extreme tooth decay. The programme compared it to chemotherapy today - a debilitating treatment people used only because there was nothing else.

Chapter 15: The Stink Industries

123) In 1757, Samuel Derrick compiled and published the first edition of Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies, a highly explicit consumer's guide to the prices and specialities of the many working girls who kept rooms there. It was this area between Seven Dials and The Strand which formed the centre of Georgian London's sex trade now, entering the language in slang phrases like "a Covent Garden nun" (for whore) and "Covent Garden gout" (meaning a dose of the pox). Modern reprints of Harris's List are available today and it makes an entertaining read.

124) The new factories also stretched into neighbouring Lambeth, where one 18th century press report claimed a local gang had been digging up bodies from the graveyards to harvest their fat for candles, their bones for alkali and their flesh for dog meat. As Peter Ackroyd points out, this report is both lurid enough and vague enough to suggest the story's apocryphal, but it does provide a chilling prophesy of the real grave-robbers who'd later target Cross Bones itself.

125) St Saviour's signed a lease for Cross Bones under the parish's own name in 1820 and finally acquired freehold of the site in 1863. That was the year the Bishop of Winchester's remaining rights over the Clink Liberty passed to the Church of England's Ecclesiastical Commissioners, which is what made the transfer of freehold possible.

126) Jones and Harwood, which I've written about here, is just one example.

127) England's Mistress: The Infamous Life of Emma Hamilton, by Kate Williams (Hutchinson, 2006).

128) That's certainly the view taken by Niki Adams, a spokeswoman for the English Collective of Prostitutes, who I happened to hear speaking on the radio while preparing this piece. "With benefit cuts, increased homelessness and increased unemployment, many women, particularly mothers are going into prostitution and find that it's a better choice than other choices available at the moment," she said. "Why is it more degrading to work in the sex industry than skipping meals to feed our children, begging on the streets or working in low-wage jobs?" (Today, BBC Radio 4, December 4, 2012).

Chapter 16: Say my name

129) It was not necessarily the pauper's place of death that decided which parish must pay for her funeral, but rather her place of settlement. A St Saviour's pauper who happened to die while visiting St Olave's Parish, for example, would still have been St Saviour's responsibility to bury. I'll return to this point in a moment.

130) Each parish kept its own burial register, but these do not distinguish between the individual burial grounds the parish had at its disposal. St Saviour's, for example, used three different burial grounds within the parish boundaries, of which Cross Bones was only one.

131) Green doesn't mention it in the programme, but the camera's shot of this entry shows the additional words ".and pleuritis". That's the lung inflammation we'd today call pleurisy.

132) Forefathers, a poster on the Rootschat board, found a girl called Elizabeth Mitchell in the census book of 1851. She's listed as 21 years old, head of a household in Mint Street (just round the corner from Cross Bones) and gives her trade as shoebinder. The census taker notes her place of birth as Portsmouth in Hampshire and adds a tick against her name in the column marked "Whether born blind or deaf and dumb". We know that year's census data was gathered five months before the BBC's Elizabeth Mitchell died and the age given is within a reasonable margin of error. Are they both the same woman? Perhaps.

133) I sent Green my query at 4:08 one afternoon and his reply arrived at 4:18. Two-and-a-half years had then passed since Crossbones Girl was first aired and I got the impression he'd been waiting for someone to ask this question ever since.

134) We shouldn't assume that the deceased's family accepted a pauper burial lightly either. George Downing, the secretary of one burial society, said in 1843 that poor people would sooner "sell their beds from under them" than subject loved ones to a pauper funeral. "It is heart-rending to them," he adds.

135) "It's a cruel disfigurement, because preferentially it wants to go to your face," Black added. "It [creates] the kind of face that children would cry at - and that's quite sad for someone who's so very young."

136) You can buy a copy of Crossbones Girl for just £1.89 in the iTunes store. I do urge you to see it for yourself, because it's a fascinating detective story and I've only scratched the surface of its content here.

Chapter 17: Resurrection men

137) However unsavoury this practice sounds to modern ears, we must remember that it laid the groundwork for every surgical procedure saving lives today.

138) William Osler was chief physician at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and the visitor writing here was his uncle. Rectified oil of turpentine was known as "ol. Terebinth" at the time and seems to have been employed here as a disinfectant.

139) Poet-Physician: Keats & Medical Science, by Donald Goellnicht (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984).

140) "Once Keats got used to the stink, maggots and livid colours of decaying flesh, no doubt he joined in the robust jokes that steadied them in their work," writes the poet's biographer Nicholas Roe. Distancing yourself in this way must surely be a necessary part of mastering such work.

141) Orme's comments here come from our exchange of e-mails in November 2012.

142) By 1822, people's fears about grave-robbing had become so great that undertakers started supplying metal coffins to those who could afford them. The extra weight of these coffins increased costs for every other aspect of the burial too and an 1822 St Saviour's price list shows such burials charged at over £12 for adults and nearly £10 for children. The result was to ensure metal coffins could be used only by the rich and hence left the poor more vulnerable than ever. If you could afford a metal coffin, you could afford a better burial ground than Cross Bones too, so I doubt they ever troubled the grave-robbers working there.

143) The Corpse King, by Dorothy Davies (2007) is available on Authorsden.com.

144) The Bodysnatcher's Apprentice, by David Orme (Kindle, 2012).

145) Report From The House of Commons Select Committee on Anatomy, 1828 (available as a free Goggle e-book, starting from page 14 here. The four resurrectionists who spoke before this committee were given immunity in return for their co-operation.

146) The Diary of a Resurrectionist 1811-1812, edited and commented upon by James Blake Bailey (Rarebooks.com, 2012).

147) The fact that the gang who shopped Brookes did so at Union Street police station (which is just around the corner from Cross Bones) suggests the undertaker was sited on that station's patch. It's possible that the corpse was destined for Cross Bones when stolen and still ended up there after its recovery. One St Saviour's undertaker produced an 1838 price list showing he charged one pound, five shillings and eightpence to bury an adult at Cross Bones, (equivalent to about £120 today), so the bribe must have been a lot more than that for our man to consider it worth the risk.

148) It saved the ressurectionists a lot of work when they could steal a body before its burial instead of having to dig it up later, so they often recruited accomplices like the undertaker here. Corrupt workhouse officials would fiddle the paperwork to make deaths in their own establishment disappear, then have the resurrectionist collect those bodies overnight.

149) By 1811, Crouch had gotten so used to throwing his weight around that he actually called the Borough Boys out on strike, demanding still higher prices for the bodies they supplied. The surgeons managed to tough-out this dispute by employing amateur body-snatchers instead, forcing Crouch and his men to resume work at their old rates. Many surgeons who'd dealt with the "scabs" during Crouch's strike later suffered the sort of revenge break-ins described in the main piece.

150) Sir Astley also pressurised Guy's Hospital into giving his incompetent nephew Bransby Cooper a surgeon's job there. In March 1828, The Lancet published a scathing account of a botched operation by Bransby which lasted over an hour and killed a patient whose life had not previously been in danger. "Not only did Cooper lose his way anatomically, he lost his head," The Lancet says. "His panicky use of instruments and his barked and desperate orders to his assistants were observed by a number of his surgical colleagues."

151) Bdy-snatching is not just a historical phenomenon. In its April 2, 2012 issue, The Economist described a 3,000 year old Chinese custom called ghost marriage, which is still practiced in rural areas. Families whose loved one dies unbetrothed buy another family's corpse of the opposite sex - often spending many years' income on this - then bury the two bodies together in a shared grave with a ceremony combining both funeral and marriage rites. "In Hebei province in February this year, an 18-year old man surnamed Lui, who died of heart disease, was joined in a ghost marriage with a 17-year-old woman named Wu," the magazine reports. "Their honeymoon was cut short soon after, however, when grave-robbers snatched Ms Wu's body, reselling her into another ghost marriage in a neighbouring province."

Chapter 18: John Crow's megaphone

152) Or are you? Perhaps Rivlin's ruling means the undertaker's embalming work could be held to transform a body into property too. Details of Kelly's trial and conviction appear on the BBC News website here and here.

153) Piccadilly Circus - or just "the 'Dilly" as it's called here - is a central London area where prostitutes and rent boys have traditionally gathered. "The 'Dilly" later became a general term for any such street in police and criminal slang.

154) I love this little verse for the way it condenses the girl's childhood, sexual awakening, working life and death into the passage of a single week. But Walsh may be pulling our legs when he labels it "old rhyme, c. 1880". Cassell's Dictionary of Slang dates "working girl" as a term for prostitute no earlier than the 1930s and as far as I've been able to discover, "lipstick" in the sense used here first appeared about 1920. If both these terms really were around in 1880, then the lexicographers have some re-writing to do.

155) Jimmy Cauty (aka Rockman Rock) is not only a musician, but also a witty and imaginative arts prankster. This vimeo film gives a pretty good primer on his antics to date.

156) As far as I know, Banksy's never responded to this invitation. As we've seen with the recent auction sales of his graffiti pieces (many of which have been chipped from the owner's walls under somewhat dubious circumstances), his prices have now risen to a point where any Cross Bones tarmac he decorated might well be worth removing intact for sale by the developers. It could even end up adding to their profits from the site.

Chapter 19: Seeking closure

157) The minimum depth officially then allowed for burials at Cross Bones was four feet, or twice the minimum depth actually used. In patches where it was possible to dig much deeper, the sexton Mr Drewett explained, he buried the first coffin as deep as 16 feet, stacking later ones on top in the underground towers MoL archaeologists would later find there. "My system has invariably been to go to 14 or 16 feet where an opportunity offered, without respect to pay," Drewett wanted the vestry to understand. "The same has been done with parish and workhouse funerals, where I had no prospect of remuneration whatsoever."

158) In fairness to St Saviour's churchwardens, it was their responsibility to find somewhere in the parish where the huge influx of cholera victims could be buried. Quick as the vestry's critics were to condemn the state of Cross Bones, I doubt they offered much of an alternative.

159) You'd be in no hurry to empty an under-floor cesspool like the ones mentioned here, but the task had to be faced eventually. This was done using buckets carried in and out through the house, with all the casual spillage that implies.

160) Sir Edwin Chadwick, secretary of the Poor Law Commission, produced his report from this enquiry in 1843. You can find Wyld's contribution extracted in the Provincial Medical Journal of January 13, 1844.

161) Take note of that "18 inches". Now even the two-foot minimum depth considered inadequate back in 1832 could no longer be maintained.

162) Gatherings From Graveyards, by George Alfred Walker (Longman, 1839). Available as a free Google e-book here.

163) These 20,000 coffins stacked nine deep would make 2,222 "towers" altogether. Equally spaced in an acre's 4,840 square yards, each stack would get just over two square yards of surface area to itself. The depth would be even tighter, with each coffin given just 16 inches of the 12-foot hole Haycock mentions. It's a squeeze but, in an age when Londoners were rather smaller than they are today, just about possible. Photographs from the MoL's 1993 Cross Bones dig suggest a very similar density was achieved there.

164) This made me think of Christopher Hitchens describing the bloodstained dirt he found blowing into his own lungs as he stood next to an Iraqi mass grave in July 2003. "I hope never again to feel so utterly befouled," he writes in 2010's Hitch-22. "It was in the nostrils, in the eyes . on the tongue and in the mouth."

165) Thomas Hardy caught the flavour of this bone house slop well in his 1882 poem The Levelled Churchyard: "We late-lamented, resting here / Are mixed to human jam / And each to each exclaims in fear / 'I know not which I am'."

166) A Microscopical Examination of the Water Supplied to the Inhabitants of London and the Suburban Districts, by Arthur Hill Hassall (Samuel Highley, 1850).

167) The result of S&V's inaction was that, when cholera struck London again in 1854, Southwark once again showed the highest mortality in the city. That was also the year in which John Snow's epidemiology study of the neighbourhood served by a Soho water pump proved that cholera is primarily spread by dirty drinking water.

168) George Cruikshank, who illustrated many of Dickens' books, produced a scathing 1832 cartoon on the state of Southwark's drinking water. You can see it on the UCLA website here.

169) The shells Gwilt mentions here were flimsy wooden containers used to transport a body before a real coffin could be found. Victorians used them rather as we use body bags today.

170) Like many Victorian letter-writers, Mrs Gwilt had a very verbose style. For the sake of both clarity and impact, I've made a lot of small cuts to her letter while transcribing it here, but you can find the full text in the MoL's Cross Bones report (see note 96). The same goes for Lord Brabazon's letter below.

171) If anything, St Saviour's claimed, they'd gone above and beyond the call of duty with Shooter's remains. The parish chaplain had refused to wait any longer for the delayed coroner's warrant and buried the body anyway, thus "rendering himself liable to a penalty for doing so".

172) St Saviour's letter lists all the individuals involved here, giving us a reliable list of at least six people we can be sure were buried at Cross Bones. They were: Elizabeth Frances Lock (aged 4), died July 23, 1849 and buried next day; Harriet Horton and Mary Ann Priest (ages unknown), both taken to the dead house on July 24 and buried next day; Michael Leary (aged 8), died August 2 and buried next day; Mary Evans (aged 68), died August 6 and buried next day; Walter Cook (aged 14), found dead in the river on August 10 and buried next day. The seventh name mentioned is Charles Shooter (age unknown), the Blackfriars Bridge suicide, who was found dead in the river on July 22. St Saviour's would say only that he was buried "in one of the cemeteries" on July 25.

173) In transcribing Mrs Gwilt's letter, I've cut out one claim altogether. The cholera woman, she says, "actually broke a blood vessel trying to get out [of her coffin shell] whilst being carried along, she not being dead then". That smells like an urban myth to me and St Saviour's replied the tale was "entirely erroneous, no such thing ever having occurred".

174) The London Gazette, launched in 1665, is the British Government's official journal of record. Its role is to print all manner of official government announcements to ensure they're available somewhere in the public record. It carried many warnings to overcrowded city graveyards at about this time.

175) It's at this point that any remaining sympathy I had for St Saviour's evaporates. Spending parish money on expensive legal advice to combat the Board of Health smacks more of hubris than any genuine concern for the people round Redcross Way.

176) Mariane Gwilt's husband George is among this letter's signatories. He was an architect, who drew up some plans of Cross Bones in 1821.

177) A year after Sutherland's report, St Saviour's was still showing some of the highest cholera deaths in London. Statistics published in The Times of November 9, 1853, show St Saviour's then accounted for 12% of all the cholera deaths in London and 20% of those south of the river.

178) Sydenham lies south of Southwark in the neighbouring borough of Lewisham.

179) The whole of London had a burial crisis on its hands at this time, which spawned a lot of private cemetery companies hoping to profit by making new land available. The London Necropolis Company, which I've written about elsewhere on PlanetSlade, ran corpse trains out of London's Waterloo Station to a new cemetery at Woking in Surrey.

180) Brabazon was chairman of London's Metropolitan Public Garden, Playground & Boulevard Association. His two letters appeared in The Times on November 10, 1883 and December 22, 1883, respectively.

Chapter 20: What happens next?

181) You can find the ad on Deloitte's website here.

182) Financial Times, November 9, 2012.

183) Student (his professional name) was speaking for the International Union of Sex Workers

Box copy

184) St Saviour's parish workhouse was in Mint Street, which lies just 300 yards from Cross Bones. This area was "surrounded with every possible nuisance, physical and moral," The Lancet wrote in 1865.

185) Posting in response to a 2008 Cross Bones video on YouTube, an archaeologist using the name Kuniklos reported finding a monastery well containing the bones of newborn babies. The team's conclusion was that mothers whose illegitimate babies had died without baptism used the well to "bury" their bodies. "The well was on abbey property, so it's as close as the little ones would get to a proper burial," Kuniklos says.

186) Thomas Hardy's 1891 novel Tess of the d'Urbervilles has a scene showing just how much pain this issue could cause. When Tess's baby dies before it can be baptised, she refuses to accept the vicar's ruling that it must be buried in unconsecrated ground. "The baby was carried in a small deal box, under an ancient woman's shawl, to the churchyard that night and buried by lantern-light, at the cost of a shilling and a pint of beer to the sexton," Hardy writes. How many dead babies made their way to St Saviour's own churchyard under similar circumstances, I wonder?

187) Exchange of e-mails, November/December 2012. Boulton added that fully half of Newcastle's burials in the late 18th and early 19th centuries took place in the city's unconsecrated Ballast Hills graveyard for reasons of cost.

188) There's a scene is Charles Dickens' Bleak House where Lady Dedlock and Jo, a young crossing guard, visit a ramshackle pauper graveyard much like Cross Bones. When Lady Dedlock asks Jo if the ground is "blessed", he replies: "Blest? It ain't done much good if it is. Blest? I should think it was t'othered myself."

189) In 1617, Bankside stewholders complained that innkeepers in the High Street had blocked an old alleyway which previously gave their customers a convenient short-cut to the riverside brothels. The court ruled they'd been trying make lazy punters spend money in the High Street's own whorehouses instead.

190) The British Museum's print room has a Bill Crook engraving showing this row of stewhouses as it appeared in 1547. He's helpfully labeled each one with its name and identifying symbol.

191) This joint gave its name to Rose Street in Southwark, which survives as Rose Alley today. "Plucking a rose" became an Elizabethan euphemism for sex, probably because that street was so packed with whores.

192) Exchange of e-mails, August 2013.

193) At the other end of the spectrum were Southwark's cheapest, no-frills whorehouses. "In the lowest class of brothel, there would be no entertainment but plenty of liquor and the girls worked till they dropped," Burford writes.

194) The Picara: From Hera to Fantasy Heroine, by Anne Kaler (Popular Press, 1991).

195) "Under James' benevolent if drunken eyes, the Bankside amusement park flourished as never before," Burford writes.

196) Early forms of condom were available in England in the 1600s, but they never caught on in the Bankside brothels. Throughout the stewhouse era, Bankside's girls relied on little more than a good hard piss and a wipe-cloth soaked in wine or vinegar to protect them from pregnancy and VD alike.

197) The Pope saw such marriages as a way for honest men to redeem former whores.

198) Cross Bones lies in the stretch of Redcross Way between Southwark Street and Union Street, with the Boot & Flogger pub (10-20 Redcross Way) directly opposite its gates. Houses numbered 1-9 Redcross Way are just on the other side of Southwark Street, less than 150 yards from the burial ground itself.

199) Old Bailey trial transcripts: January 29, 1838.

200) Child witnesses like Grant (who'd never learnt to read) would take their oath in the Victorian courts by reciting The Lord's Prayer from memory. This was felt to show they knew the difference between right and wrong and so would not casually lie about what they'd seen. Grant had failed to clear this hurdle at the coroner's hearing, but a priest taught him the prayer in time for him to testify at the Old Bailey.

201) Human teeth at this time could be sold to dentists, who assembled them into sets of dentures for their customers. These sets were later nicknamed Waterloo teeth, because so many of them came from the casualties of that 1815 battle.

202) Fifty guineas in 1815 would be worth about £4,000 today.

203) A gentleman's gentleman was a rich man's personal valet - precisely the job Jeeves held with Bertie Wooster. What on Earth must Light have been like in that role?

204) We can get an idea of the living conditions at Redcross Way in Lofthouse's time from DrWot's YouTube interview with Joyce Newman, whose mother was born there in 1895. "It was old-fashioned buildings, with just one wash-house on the landing for three or four blocks and they were about five stories high," she says. "They were terrible places."

205) Lofthouse was Alice's married name, taken from her estranged husband, the soldier William Lofthouse. Some reports of the case call her Alice Fisher, which I assume was her maiden name. She was still married to William Lofthouse when she died.

206) Old Bailey trial transcripts: September 13, 1898.

207) The Sun, July 18, 1898.

208) Daily Mail, July 20, 1898.

209) "Fatty" was William Gould's nickname.

210) Daily Mail, July 27, 1898.

211) Curing Hooliganism: Moral Panic, Juvenile Delinquency & The Political Nature of Moral Reform in Britain 1898-1908, by Ian Livie (University of Southern California Phd dissertation, May 2010).

212) Burke's 20 shilling fine would translate to about £110 today.

213) South London Chronicle, July 23, 1898.

214) Page, Burke and O'Connell may well have been tied up in the gang's activities too, either as whores of simple hangers-on.