On the morning after the Cross Bones vigil, I gathered a few offerings of my own for the gates and prepared to set off for Redcross Way again.

On the morning after the Cross Bones vigil, I gathered a few offerings of my own for the gates and prepared to set off for Redcross Way again.

I'd gone along the previous evening expecting one of the site's routine monthly ceremonies, planning to return with my gifts when the full Halloween ritual came round in a week's time. Instead, I'd arrived at the gates to discover a flyer announcing that evening's proceedings would fold both October ceremonies into one. "This is our 101st consecutive vigil and will feature elements from the Halloween of Crossbones ritual drama (1998-2010), including the names of the dead," it explained.

I asked Constable later why they'd decided to do this and he replied that everyone simply needed a rest. "We did 13 Halloweens and we might do another cycle of them sometime," he told me. "But it was quite good to do 13 and then have a break, because it was an awful lot of work to do them. When we stopped, we moved some of those Halloween elements to the 23rd of October."

It was that first Halloween procession in 1998 which began the tradition of decorating Cross Bones' gates with all the ribbons, costume jewellery and lace they've sported ever since. A few days after the 1998 procession, the first of the site's homemade plaques appeared too. "A plaque has mysteriously appeared commemorating the Southwark prostitutes who were buried in unconsecrated, forgotten graves," the South London Press reported. "Playwright John Constable, who has long campaigned for the working women of olde Southwark to be remembered, is delighted. He first spotted the carved wooden plaque on a wall in Redcross Way." (40)

Constable takes up this story in The Southwark Mysteries. "The plaque, adorned with varnished flowers, was widely believed to be the work of a local working girl called Emily," he writes. "It read: 'To fix in time this site, the Crossbones Graveyard where the Whores and Paupers of the Southwark Liberty, in graves unconsecrated, lay resting. Where now, at Millennial turning, the Whores and Paupers and our Friends return, incarnate, in ritual, with tributes and offerings, to honour, to remember'."

Like many of the plaques that have since appeared at Cross Bones, this one didn't last long. "As the Halloween of Crossbones evolved into an annual event, a succession of home-made plaques regularly appeared," Constable writes. "Each was eventually vandalised, or perhaps removed by the site owners, to be replaced by a new plaque - until, in 2005, Southwark's 'Cleaner, Greener, Safer' fund paid for the official brass plaque and ivy planters which now adorn the gate." That official plaque, which has remained safely fixed to the centre of the gates ever since, reads: "Cross Bones Graveyard. In medieval times, this was an unconsecrated graveyard for prostitutes or 'Winchester Geese'. By the 18th century, it had become a paupers' burial ground, which closed in 1853. Here, local people have created a memorial shrine. The Outcast Dead. RIP."

Constable's group, the Friends of Cross Bones, had put the site forward for one of Southwark Council's official blue plaques four years running by the time the brass one appeared, but always lost out to more prestigious sites in the Borough. "One year we were up against Shakespeare's Rose Theatre," he told me. "They're an international trust and they were getting votes from all over the world. Once we got the brass plaque, we thought that's actually better in some ways."

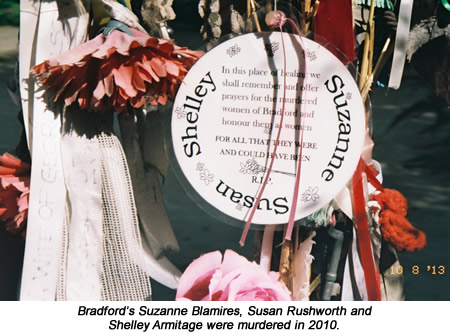

Several other home-made plaques have joined the brass one on the gate since, the most touching of which are the laminated cardboard ones memorialising the street prostitutes murdered in Britain today. They're a sobering reminder of how little has changed for women pursuing this most dangerous of trades and of how casually such woman are murdered and thrown away. Here's just a few examples, the first two of which are close enough in style and wording to suggest they were placed there by the same people:

* "Gemma, Anneli, Paula, Netty, Tania: In this place of healing where the Wild Feminine is honoured and celebrated for all that she is - whore and virgin, mother and lover, maiden and crone, creator and destroyer - we will remember and offer prayers for the murdered women of Ipswich and honour them as women. For all that they were and could have been." (Gemma Adams, Anneli Alderton, Paula Clennell, Annette Nicholls and Tania Nicol were killed by Steve Wright in 2006.) (41)

* "Suzanne, Susan, Shelley: In this place of healing, we shall remember and offer prayers for the murdered woman of Bradford and honour them as women. For all that they were and could have been. RIP." (Suzanne Blamires, Susan Rushworth and Shelley Armitage were killed by Stephen Griffiths in 2009/2010.)

* "In memory of all the women who died whilst working in the oldest profession, who the rest of society chose not to remember: Jane, Caroline, Rachel (2000), Tracey (2001), Sarah, Tina (2002), Fiona (2003), Hashley, Deborah, Tracey (2004), Samantha, Ellen, Sam (2005), Emma, Zoey, Michelle (2006), Caroline, Julie (2007), Sonia (2008), Miss P (2009), Kim, Ann, Joanne . a few to name. It's not just another day! It's not just another Death! In memory of all the workers never forgotten - POW staff, Nottingham." (POW is Nottingham charity formed by the city's prostitutes themselves to offer health information, counselling and education.)

Everything I'd read about the Cross Bones Halloween ceremonies suggested that was where the gates' most colourful supporters gathered, so I was sorry I'd missed the chance to take part in one myself. "Political activists, evangelical Christians, locals, rough sleepers, actors, former addicts and passing tourists as well as the regular pagans and sex workers turn up," the Financial Times' Kesewa Hennessy wrote after her own Halloween visit to the gates in 2008. (42)

That year's event had begun, as they always did, in the basement bar of the Hop Cellars in Southwark Street. Katherine Angel of The Independent was there too, waiting nervously at the back of the room as Constable swept in wearing his long black cloak and announced they were ready to begin. (43)

"A priestess started things off, leading us in a meditative moment of humming," Angel writes. "A single note was held, surprisingly tunefully, by the crowd. I felt a space open up in the room. My ears, my whiskers, perked up; I was suddenly alert and curious. A witch broke into a rap. Someone then asked us to close our eyes and think of the dead. To think of past pain, past loss, past regret - and let these go. We each read out a word: light, compassion, generosity - things to wish for and cherish.

"Constable then took over, adopting his persona of John Crow, his 'trickster-shaman'. Actress Michelle Watson became the Goose, a prostitute on the Bankside, a wise and sassy creature radiating erotic scorn. Together, Crow and the Goose performed, in verse and song, sections of Constable's poetry, bringing to life the women refused burial on consecrated ground by the very Church that licensed their practice.

The Crossbones campaign celebrates a strong, elemental and witchy female sexuality. This is the language Crossbones speaks most eloquently through the 'Whores d'Ouvres' of the Halloween event: two women in basques who schooled us in the spiritual potentials of our pelvic floors. We held hands with our neighbours, breathed and moved our hips in unison - a lesson in spiritual burlesque." (44)

Dr Adrian Harris of Winchester University adds a few more details in his own account of a Halloween ritual at the Hop Cellars. "The performances consisted of songs and poems from The Southwark Mysteries and a demonstration of Tantric breathing from Jahnet de Light and her Whores d'Ouvres," he writes. "Many people, especially the women, were in fancy dress. But instead of the usual 'trick or treat' ghouls, they sported the Elizabethan costume of the commoners - just the kind of garb that would have been worn by the 'Winchester Geese'. The large basement room was decorated with flowers and two altars; one for our own beloved dead was designated as an 'Altar to the Ancestors'. The other was dedicated to the prostitutes of Crossbones. This latter altar was laden with suitable offerings: chocolate, cigars and a bottle of gin." (18)

Constable confirmed these accounts when I asked him what I'd missed by not being able to attend a full Halloween ritual. "With the Halloween ones, we went as close as I would go to doing a proper magic ritual," he told me. "I've always said we do a kind of magic at the gates, but it's the sort of magic you can do in the open. That's the thing about the vigils: we only do stuff there that anyone, whether they're a pagan, a Christian or a happy atheist can participate in without feeling weird about it. So the vigils are very much shaped by that.

"The Halloween ceremony obviously pushed that envelope a bit. When we did it at Halloween, we'd have a Samhain ritual to greet the New Year and people would bring photos of their own dead. Then we'd have performances from selected poems in The Southwark Mysteries and the third element would be the Goose's tantric teachings. We'd always have a tantric sex worker, who would lead a simple workshop. Everybody kept their clothes on, but it was interesting. People would be holding hands and inwardly squeezing their pelvic muscles and all of that. We'd end with a procession to the gates, where we'd read the names and tie the ribbons."

Introducing too many of the Halloween ritual's freakier elements into the mainstream monthly vigils, he added, would risk putting off anyone who found the gates' memorial role interesting but ran a mile from anything that smelt of new age twaddle. People like me, in other words - and perhaps like many of those crowded round the gates with me on that October evening too. "I like the fact that we get all sorts there," Constable told me. "There's a couple of ladies well into their eighties who come a couple of times a year - churchgoers, not the sort of people you would expect there at all. And that's what I love. We are genuinely an eclectic group of people, of all kinds. The thing with the vigils is, you can just turn up and fully participate without needing some sort of initiation into it."

You'd think rapping witches and a spot of pelvic squeezing would be enough for anyone attending the Halloween ceremony, but some insist matters don't stop there. In The Londonist's October 2012 podcast, Quentin Woolf interviewed Constable and a Dulwich activist called Ingrid Beazley together on location at the Cross Bones gates. "We were sitting on the floor and we were handed a little round mirror," Beazley told him of one Hop Cellars ceremony she'd attended. "And on the mirror was engraved 'You are Beautiful'. It was for the women and we were supposed to look at our fannies with it." Woolf moved on before Constable had a chance to comment on this in the recording itself, but the memory still rankled when I interviewed him a year later. "I remember it well - it was a male sex worker who handed out the mirrors," he told me. "But she remembered him saying, 'It's for women to look at their fannies with' and I don't remember that at all. I remember him saying, 'You look at yourself in it' - your face. Which makes a lot more sense."

All this information was buzzing through my head as I sorted through my own offerings on the kitchen table. The Altar of the Ancestors which Harris describes sounded a lot like the Day of the Dead shrines I'd seen in Mexico and Texas, so that's where I started my trawl. I've been collecting Day of the Dead figures for years - tiny clay statues with skulls and boney hands, each dressed to embody a certain job or personality type: the priest, the tycoon, the drunkard, the gambler and so on.

All this information was buzzing through my head as I sorted through my own offerings on the kitchen table. The Altar of the Ancestors which Harris describes sounded a lot like the Day of the Dead shrines I'd seen in Mexico and Texas, so that's where I started my trawl. I've been collecting Day of the Dead figures for years - tiny clay statues with skulls and boney hands, each dressed to embody a certain job or personality type: the priest, the tycoon, the drunkard, the gambler and so on.

From these, I chose a street urchin hawking newspapers and a smartly-dressed businessman with a briefcase. The first figure, I thought, could represent both my own trade and the humble folk of Southwark's past, while the second stood in for the local whores' wealthy johns and the financial whizz-kids whose shiny office blocks now threatened to crush Cross Bones' underfoot. Somewhere in Texas, I'd bought a cheap necklace of 16 clay beads on a nylon string, each shaped and painted like a skull, which had been languishing in a drawer ever since. Now, at last, I knew where it belonged.

To these items, I added a small plastic doll of Lois Lane I'd somehow acquired. Clad in green micro-skirt, black knee-length leather boots and with a large "city-gal" handbag slung jauntily over her shoulder, she had just the feisty sex appeal needed to do the Goose justice. A few days earlier, I'd bought two plastic miniatures of Gordon's Gin to use as Cross Bones offerings, so they went in the bag too.

The final item returned me to my Day of the Dead souvenirs, where I found a cheap picture frame made from beaten tin, which Mexican mourners would typically use to hold the picture of a departed loved one on their family shrine. Like the necklace, this frame had been something I'd failed to find a home for ever since bringing it back to England, but now its true purpose was clear. It was as if the necklace and the frame had been waiting all this time - ten years or more - until it finally dawned on me that they belonged on the Cross Bones gates.

I knew just which picture to put in the frame too. Nasra Ismail was the Somali-born prostitute murdered near King's Cross in March 2004, whose story I've told elsewhere on PlanetSlade. Her dismembered body was found in a canal close to my home and it had struck me at the time that someone should at least try to remember her name. My first attempt at that had been to write some murder ballad lyrics about her death, but giving her a spot on the gates seemed even more appropriate. I fixed a photocopy of her picture into the tin frame, added her name and date of death, then threaded some wire through the frame's corners to tie it on with.

Down at Redcross Way, I fixed Nasra's portrait to the gate's vertical bars, knotted the necklace into place a few feet to the right and wedged Lois into the knot of a convenient ribbon. The two Day of the Dead figures went just inside the gate, where the bars allowed me to reach through and place them among the burnt-out candles and debris littering the makeshift altar there. I photographed everything, then waited for a quiet moment by the graveyard's southwest corner before lobbing the two plastic miniatures of gin over the eight-foot wall into what I knew was the centre of the graves themselves. Someone will find them there one day - a tramp, a site worker, a Cross Bones volunteer - and when they do, they're very welcome to have a drink on me.