Cross Bones' modern era began around 1989, when Transport for London first drew up plans to extend the Tube's Jubilee Line out to London's massive new office developments in Docklands and Canary Wharf. The site at Redcross Way, then just a patch of derelict land, was one of the properties it acquired in preparation for this work.

Cross Bones' modern era began around 1989, when Transport for London first drew up plans to extend the Tube's Jubilee Line out to London's massive new office developments in Docklands and Canary Wharf. The site at Redcross Way, then just a patch of derelict land, was one of the properties it acquired in preparation for this work.

John Constable had moved to Southwark about three years earlier, not because he had any particular interest in the Borough, but simply because he'd happened to find an affordable flat to rent there. "It was regarded as a very run-down and dubious area," he told me. "Taxi-drivers would not bring you home here and policemen warned me about drawing out cash. On the other hand, although it was quite beat-up, it was also an amazingly atmospheric area, with loads of interesting little twists and turns in the back streets. It was full of derelict warehouses and some of those had been either taken on as short leases or squatted. As a result, you had lots of artists' studios, unusual spaces and clubs operating."

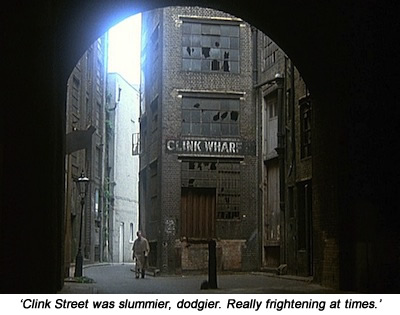

This was the era of London's first warehouse parties and the beginnings of an Ecstasy-driven dance culture which would dominate the coming decade. Matthew Collin's 1997 book Altered State gives us a glimpse of what Southwark was like as the warehouse parties began. He starts with the story of Paul Stone and Lu Vukovic, who had been among the dancers at West London's groundbreaking Hedonism club and decided to create a similar event of their own. "They booked some rooms in a recording studio on Clink Street in the shadow of London Bridge," Collin writes. "In 1988, that warren of streets was dark, dilapidated, desolate and sometimes rather frightening. The only sign of humanity was the nearby market, which would spring into life just before dawn, the lorry drivers and traders bemused at the danced-out, dishevelled clubbers wandering home sweaty and exhausted." (95)

Stone and Vukovic called their club RIP (for Revolution In Progress) and created what Collin calls a "deliciously edgy" atmosphere there. Among the core DJs they used were Mr C and Eddie Richards, both of whom share their memories of the club in the book. "Every week, there were people trying to climb up drainpipes, giving backhanders of £20 to the doormen to get in, doormen having to fight people off with baseball bats and dogs because they were going to rush the doors," Mr C recalls. "Complete madness." Richards confirms this picture, contrasting RIP with more respectable dance nights nearby. "Clink Street was slummier, dodgier," he tells Collin. "Dodgier characters on the door, dodgier characters inside, a dodgier feeling about it. I think it was a bit frightening - really frightening at times."

Among the villains and thugs Mr C remembers thronging the RIP dancefloor were an equal number of the stylish rich, hip enough to know this offered London's most intense night out, dressed to the nines and pestering the acid house kids in their day-glo tracksuits for a fresh supply of pills. Clink Street and its surrounding Liberty had hosted this unlikely mix of rich, poor and criminal pleasure-seekers for centuries and now the area was pulsing with that old anarchic energy once again.

Meanwhile, just a quarter-mile to the south, TfL was surveying its new Redcross Way site. Excavations on the scale they planned would inevitably disturb significant archaeological sites all along the extended route, so regulators had insisted the Museum of London be given a chance to mitigate any damage caused. When the museum's archaeological team heard the Tube wanted to build an electricity substation at Redcross Way, that's when they stepped in. "The site was known from documentary sources to be the location of a burial ground used during the post-medieval period," the MoL team wrote in its later report. "A small-scale investigation in 1990 was carried out by the Oxford Archaeology Unit which showed the documentary evidence was correct." The museum won permission to carry out a dig on the footprint of the proposed sub-station, but was given just six weeks to get it done. (96)

The five-strong MoL team got to work on the site in February 1993. They worked only on the sub-station's footprint itself - an area equivalent to about two-and-a-half tennis courts - and dug down just 10 feet. In this single "box" of earth alone, they found 148 skeletons buried. The museum estimates this to be "less than 1%" of the total number of burials made at Cross Bones, suggesting the site as a whole provided a last resting place for at least 15,000 souls.

All the human remains under the sub-station's footprint were removed at the conclusion of the six-week dig - not just those in the first ten feet but all the way down. Those in the rest of Cross Bones remain undisturbed. "We are now standing on untouched burial ground," MoL's Adrian Miles told a BBC interviewer on the site in 2010. "There are several thousand burials beneath our feet. All the burials were in coffins, but they're of the poorest standard that I've ever seen. You're looking at re-used wood - it's probably cheap wood that's coming off the docks." (97, 98)

The whole of Cross Bones covers only about 2,000 square yards, as Patricia Dark reminded me when we discussed the MoL's estimates. "It's not big," she said. "It must be absolutely chock-full of bones." The MoL's photographs from its dig confirm this, showing coffins packed so closely together that their sides are almost touching. Layer after layer of dead were found crammed into the Cross Bones earth, with coffins sometimes stacked nine or ten deep. The top layer was just a few inches below the surface. Only a few of the coffins had nameplates attached and even those were of such poor quality that they'd long since become illegible. As with the ramshackle coffins themselves, the families who used Cross Bones simply hadn't been able to afford anything more durable.

All the bodies were buried on their backs, aligned east-west with their feet at the eastern end. This custom was observed in the belief that, when the Resurrection came, the dead would be able to sit bolt upright in their graves and immediately see the glory of the risen Christ in the east. As we'll see a little later, one unforeseen consequence of this practice was to tell grave robbers exactly where they should dig in any particular plot to get the corpse out with minimum fuss. (99)

The museum's analysis of the 148 skeletons it recovered gives us a fascinating picture of just who was buried at Cross Bones. Because these were the bodies closest to the surface and because they knew Cross Bones' graves were so regularly recycled, the team assumed all the burials concerned had been carried out in the site's final fifty years of use. That put the individuals' date of death at somewhere between 1800 and 1853, a period which takes in the first 16 years of Queen Victoria's reign.

"By the time we're excavating it, it's very much the poor ground for the parish of St Saviour's," Myles told the BBC. "The people who would be buried here would be the poor of the parish, bodies found in the river, people from the workhouse, people who couldn't afford to pay for their own burials."

Just over two-thirds (70.2%) of the skeletons uncovered were those of children, this group representing 104 of the 148 skeletons in all. At least 98 of those 104 children had been six years old or under when they died, reflecting this part of Southwark's very high infant mortality in the first half of the 19th Century. In London's poorest parishes - of which St Saviour's was definitely one - as many as one in three children then died before their fifth birthday. The biggest single group of children were the perinatal ones, who died either in their mother's final three months of pregnancy or within a month of birth. There were 50 skeletons like this in the 148 MoL studied, representing a third of the grand total and nearly half of all the children involved. Next came those aged between one month and six years (48 people), aged from six to 11 (two people) and aged 11 to 18 (one person). There were another three skeletons which the museum was confident had belonged to children, but which were impossible to age beyond that. (100)

The adult skeletons - 44 of them in all - were mostly aged between 36 and 45 (18 people), with the next most common groups being aged 46 or more (14 people), 26-35 (four people) and 18-25 (three people). There were five adult skeletons the team was not able to age any more precisely than that. Of the 39 adult skeletons it was possible to sex, 12 were male (31%) and 27 were female (69%). The biggest tranche of men were aged 36-45 at death (six people) and the biggest tranche of women aged over 45 (12 people).

Turning to the question of these people's medical history, the MoL's findings were these:

• Periostitis was present in 89 of the 148 skeletons studied (60.1%). This disease attacks the connective tissue coating human bones and causes severe pain. When a mother with syphilis passes that infection to the child in her womb, it can cause periostitis in the newborn baby. In a graveyard with as many infants in it as Cross Bones, that seems likely to be a major factor.

• 59 skeletons (40%) showed signs of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is still very common in the UK, but today it normally hits people over 50. Only 14 of the 140 people it was possible to age at Cross Bones (10%) got to more than 45, suggesting the disease struck much earlier then.

• Twenty-two of the skeletons (14.9%) had signs of scurvy. Scurvy is caused by a lack of Vitamin C and we know most of the people round Cross Bones had a very poor diet.

• Eleven of the skeletons (7.4%) had signs of rickets. Lack of calcium in the diet and a lack of sunshine cause rickets. People in the Southwark slums got precious little of either.

• Twelve skeletons (8.1%) had healed fractures. This category includes 50% of all the men and 14.8% of all the women. Industrial accidents and the violence of the streets may explain the high incidence of male injuries. No doubt Victorian Southwark had its share of wife-beaters too.

. Nine skeletons (6.1%) showed evidence of treponemal infection, which is linked with syphilis. Seven children and two women filled this category.

• Three skeletons (2%) had evidence of surgery carried out at or very close to the point of death. It's not clear whether the surgery killed them or whether they fell prey to Victorian anatomists.

• Two skeletons (both children) showed evidence of histiocytosis-X, which can be caused by toxins in the atmosphere. Southwark was full of very dirty factories by 1800, which made the air and the water supply filthy. This group represented 1.35% of the total sample.

• One skeleton (a child's) showed evidence of smallpox infection. That's 0.7% of the total sample.

"The 19th Century parish of St Saviour's, Southwark, teemed with people - the poor and destitute, living in overcrowded houses with bad hygiene, drainage and waste disposal and an inadequate and polluted water supply," the MoL's report sums up. "[This excavation] provides a window on a population struggling with harsh living conditions, who were poorly nourished and prone to infections and deficiency diseases. Most were buried in cheap coffins and this heavily-used, ill-kept and unconsecrated burial ground contrasts with wealthy parishes elsewhere in London."

"The 19th Century parish of St Saviour's, Southwark, teemed with people - the poor and destitute, living in overcrowded houses with bad hygiene, drainage and waste disposal and an inadequate and polluted water supply," the MoL's report sums up. "[This excavation] provides a window on a population struggling with harsh living conditions, who were poorly nourished and prone to infections and deficiency diseases. Most were buried in cheap coffins and this heavily-used, ill-kept and unconsecrated burial ground contrasts with wealthy parishes elsewhere in London."

As the MoL team got on with the analysis that produced all this data, Constable was still exploring his new home. The National Lottery's Millennium Fund was pouring a fortune into this previously neglected stretch of the Thames' south bank and massive construction sites were springing up all around him. In 1993, building work started on Sam Wanamaker's replica Globe Theatre, in 1995 work began to convert the old Bankside Power Station into Tate Modern and in 1996 plans were announced for a stylish new footbridge linking Tate Modern to St Paul's Cathedral on the other side of the river.

"There was that real sense of things changing," Constable told me. "I knew Bankside was going to change out of all recognition, so one of my inspirations for writing The Southwark Mysteries was wanting to capture the moment that I was living here. On the 14th of November 1996, I got a group of friends together including Ken Campbell and John Joyce, one of his actors. There were about seven of us - we were actually a writer's group. I took them on a walk I called The Mysteries Pilgrimage and we visited Southwark Cathedral, Shakespeare's Globe, Winchester Palace, the site of the Tabard. These were already in my mind as kind of magical places. The one that was missing was Cross Bones." (101, 102)

Nine nights after that - on November 23, 1996 - Constable encountered the Goose for the first time and took down her puzzling verse: "And well we know how the carrion crow / doth feast in our Cross Bones graveyard". A month later, the MoL began briefing journalists about its analysts' conclusions from the Redcross Way dig, prompting one newspaper to warn that further development could obliterate this endangered "skull and crossbones cemetery" altogether. That phrase made Constable think of the Goose again, so he went to the address the story had mentioned and instantly recognised it as one of his stops on that mad night with the Goose. "Told you so," she whispered in his ear.

As Constable got on with writing The Southwark Mysteries, Bankside's growing rave culture was gearing up for the Millennium too. One highlight planned was a new production of Neil Oram's legendary 24-hour play The Warp, which Ken Campbell had first staged back in the 1970s. The new production was to be directed by Campbell's daughter Daisy in a network of interlinked cellars underneath London Bridge station. Organised with the help of techno-hippy guru Fraser Clark and his Megatripolis club nights, the play was supplemented by a 24-hour rave in the same set of tunnels. The first event was held at the end of May 1999, with fortnightly repeats running well into 2000. Sensing a group of kindred souls, Constable was keen to get involved.

"It was coming up to the Millennium and I was in a very Millennial mood," he told me. "I'd been writing all this stuff about the outlaws and the tantric tribe returning to Southwark and suddenly there's all these alternative people - old sixties hippies, people from the travellers' convoys, punks. They used to call it Glastonbury without the mud. You'd have the whole of The Warp going on for 24 hours. You could either sit and watch the whole show or - what most people did - you could come and go. You had three dance floors, all with different music, you had a chill space and a main performance/gallery place. I used to perform in there a lot. I was doing Southwark Mysteries stuff, Goose stuff there."

The Megatripolis events had one more surprise in store too - this time a detail which linked Millennial Southwark neatly back to the Medieval bath-houses which had given the stews their name. "For about five of the parties they even had a giant hot tub, with everybody stark bollock naked," Constable told me. It was as though the Goose had never been away.