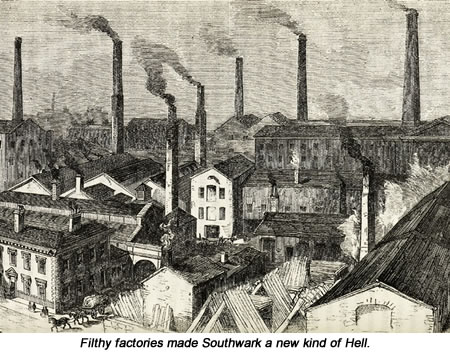

The Great Fire of London in 1666 dealt another blow to Southwark's fortunes by making many of the shops and houses on London Bridge unstable, forcing their residents to abandon the area. Ten years later, Southwark had a disastrous fire of its own, which burnt down most of the remaining medieval inns on Bankside. By the time these could be rebuilt, whatever enthusiasm pleasure-seeking Londoners could still muster for Southwark had vanished. They turned instead to central areas like Covent Garden for their fun and the Borough began its grim transformation into a centre for "stink industries" such as vinegar making and leather works. (123)

The Great Fire of London in 1666 dealt another blow to Southwark's fortunes by making many of the shops and houses on London Bridge unstable, forcing their residents to abandon the area. Ten years later, Southwark had a disastrous fire of its own, which burnt down most of the remaining medieval inns on Bankside. By the time these could be rebuilt, whatever enthusiasm pleasure-seeking Londoners could still muster for Southwark had vanished. They turned instead to central areas like Covent Garden for their fun and the Borough began its grim transformation into a centre for "stink industries" such as vinegar making and leather works. (123)

The Thames gave these industries their power, their transport infrastructure and their means of waste disposal, but wealthy Londoners were keen to keep the noise and pollution they caused at arm's length. Just as with the stewhouses that had preceded them, the solution was to concentrate such filthy trades across the river in Southwark and let the slum-dwellers there endure the consequences. As recently as the late 1500s, Southwark dye-house owners had been converting their premises into brothels because they knew there was more money to be made that way, but the 17th century saw this process jammed into reverse. In 1633, a Bankside stewhouse called the Crane was transformed into a soap factory and 60 years later even the mighty Unicorn - once one of the two biggest licensed stewhouses in all of London - became a Southwark glassworks. (124)

"By the year 1700, the Bankside had lost almost every trace of its murky past," Burford writes. "It was turning into a bleak warehouse and wharf area, with a few dye-houses and a number of public houses serving mainly the watermen and labourers who loaded and unloaded barges and other vessels. A number of breweries had also been established in the immediate hinterland, surrounded by slums."

In 1750, London opened the newly-built Westminster Bridge, about two miles upriver from Southwark, ending the lucrative 500-year monopoly London Bridge had enjoyed as the Thames' only permanent crossing. A new bridge in this far richer and safer part of the city gave people yet another reason to turn away from Southwark, speeding the deterioration there still further. In 1756, the historian William Maitland said the old Clink Liberty was now "a ruinous and filthy slum", adding that the Kent Street and Mint Street neighbourhoods surrounding Cross Bones were its worst areas of all. That was the state of the place when the Bishop of Winchester granted Edward Pearson his 1760 lease on Cross Bones, and it's very likely that Pearson was representing St Saviour's Parish when he signed it. (125)

The anarchic ghosts of old Bankside continued to surface in the Borough, first in 1772, when the Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes moved from its old Whitechapel premises to a new site in Southwark's Blackfriars Road and then with the Gordon Riots of 1780. It was also in the 1780s that the radical campaigner Francis Place - then just a small boy - watched highwaymen setting off for their night's work from Southwark's Dog & Duck tavern on St George's Fields. "Flashy women came out to take leave of the thieves at dusk and wish them success," he later wrote. It was commonly assumed that the decaying taverns around St George's Fields were the favourite meeting places for radical insurrectionaries of all kinds and the breeding-ground for all their plots.

The Gordon Riots burnt out two of Southwark's prisons - the Clink and the King's Bench - and the Clink was allowed to fall into disuse. Twenty years later, Horsemonger Lane Gaol opened in what's now Newington Gardens, adding a public gallows to Southwark's traditional glut of penal institutions. This hanged a total of 135 convicts before it was eventually closed in 1878 and appeared as a woodcut illustration on many gallows ballad sheets. (126)

Although the new factories brought jobs to Southwark, these were both dangerous and poorly paid. "Work in the soap factories or brick kilns meant a 12-hour day in steaming conditions, risking acid burn and injury," Kate Williams writes in her 2006 book England's Mistress. "Many women believed prostitution less dangerous than factory work and more bearable than domestic service. We might think these days we would rather steal or beg. Beggars, however were usually attacked and crimes against property were so stringently punished that a girl who stole a handkerchief could be executed or deported." Prostitution on the other hand, had been downgraded from a crime to a mere nuisance in 1640 and what laws remained against it were enforced intermittently at best. (127)

Williams quotes figures claiming one in eight of all the adult women in London worked as prostitutes in the late 18th century - I'm assuming this includes both full-timers and those who merely dabbled in the trade when needs must - and I've seen other estimates suggesting about a third of this total were former domestic servants. Street prostitution in any age is unlikely to match the soft-focus Belle de Jour fantasy, but we should remember also that health and safety was unknown in the hellish factories of the 18th century and that conditions for domestic servants were little better. Girls as young as 12 could earn a living in the brothels of Georgian England, but housemaids that age received no more than a bare floor to sleep on and just enough table scraps to keep them alive. Even in adulthood, they were expected to work long hours for little pay and assumed to be fair game by their predatory male employers. When the alternatives were so utterly miserable, you can see how the move into prostitution may become a rational choice. (128)

At Cross Bones itself, it was now St Saviour's Parish which decided the site's future. Parish schools and graveyards have always tended to go together for the simple reason that both are generally built on Church land. In this case, a leasehold interest in the land proved close enough and that's how St Saviour's Boy's Charity School came to be erected at Cross Bones in 1791. Like the parish girls' school that followed 30 years later, the new building faced on to Union Street, but extended at the rear over a patch of Cross Bones' burial area that was already stuffed with dead. "By the 1820s, the burial ground was completely surrounded by buildings," David Green writes in his report for the BBC. "It was, like most urban churchyards, over-full and a serious cause for concern."